Are competition appeals taking too long?

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has asked the government for additional powers to investigate firms and intervene more quickly in markets. At the same time, it wants to limit the scope for affected parties to appeal its decisions. Mark Friend, Partner and head of the London antitrust group at Allen & Overy LLP, considers whether the CMA’s arguments for reform are convincing and supported by the evidence from previous cases.

The views in this article are those of the author. The author is grateful to Jack Ashfield for assistance in collating and analysing the data, and to Andrew Fincham for commenting on an earlier draft. Any remaining errors are those of the author. A longer version of this article was posted on LinkedIn on 21 January 2020.

The CMA is advocating fundamental reforms to the competition law enforcement regime in the UK, where fines for infringements carry a theoretical maximum of 10% of global group turnover, and where the CMA currently acts as prosecutor, judge and jury. The CMA wants to see the removal of the full-merits right of appeal1 for competition law infringement decisions, while at the same time arguing that its powers should be extended to give it the ability to impose fines on individuals. In place of the current full-merits review standard the CMA would like to see either a less intrusive judicial review standard, or a new standard of review, where decisions can be appealed only on ‘specified grounds’ (as is the case, for example, under the statutory appeals regime that is applicable to licence modifications in sectors such as energy).

Why is this? The letter from CMA chairman, Lord Tyrie, in which the case for reform is set out,2 argues that competition appeals have become an opportunity for companies which have been fined for competition law infringements to have ‘a second bite at the cherry’.3 Underlying the case for change is a view that appeal hearings take too long (often lasting four weeks or more, according to the CMA),4 due to the use of oral witness testimony and cross-examination, exacerbated by rules allowing the introduction of new evidence. As a result, it is said that the UK appeals process is ‘more protracted and cumbersome’ than originally intended, making the UK (in the view of many lawyers) ‘the best jurisdiction in the world to defend a competition case’.5 In a further jibe aimed at the legal profession and the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT), Lord Tyrie argues that fines for competition law infringements are too low, and markedly lower than in some other Western European countries, weakening deterrence. This is said to be due notably to the ‘approach’ taken by the CAT in hearing appeals against CMA (and previously Office of Fair Trading, OFT) infringement decisions imposing fines. Lord Tyrie claims that fines have been reduced ‘in the vast majority of cases’, in some cases by more than 80%, adding:

[f]or those that have broken competition law, appealing against the CMA’s fining decision appears to be a one-way bet.6

It seems that the CMA believes it would be on safer ground if its decisions were judged against the less intrusive judicial review (or statutory ‘specified grounds’) standard.

A subsequent speech by Lord Tyrie to the Social Market Foundation7 points to the history of the CMA’s Phenytoin case, in which he comments that the CMA’s decision:

has been going through an appeal process for over 2 years, and is far from resolved. In a world of digital markets, that’s akin to Jarndyce and Jarndyce. [An interminable court case in Dickens’ Bleak House]

Similar claims are made in a speech by the CMA’s executive director for enforcement, Dr Michael Grenfell, who argues that the appeal process is slower than was intended when the regime was initially established, and that the system (including not just the CAT but also the CMA) therefore ‘needs to move more nimbly and swiftly’.8

The CMA concedes that delay is not just an issue at the appeal stage, noting that its own case preparation ‘can also be time-consuming’ given the complexity of many of the cases it takes on, the need to ensure careful case preparation, and the expectation that the CMA will only pursue cases ‘once it has a high degree of confidence that it will be successful’.9 The CMA accepts that more can be done to speed up cases, and proposes an explicit statutory duty to conduct investigations swiftly (although it is unclear how such a duty could ever be meaningfully enforced in practice).

But is the CMA right to pin so much of the blame for delay in pursuing competition infringement cases on the appeal process, and would a move to a judicial review (or statutory ‘specified grounds’) standard speed things up? Are appeal hearings taking too long? And finally, is there any evidence that bringing an appeal is a one-way bet?

Are appeals to blame for delay, and would a move to a less intrusive standard of review help?

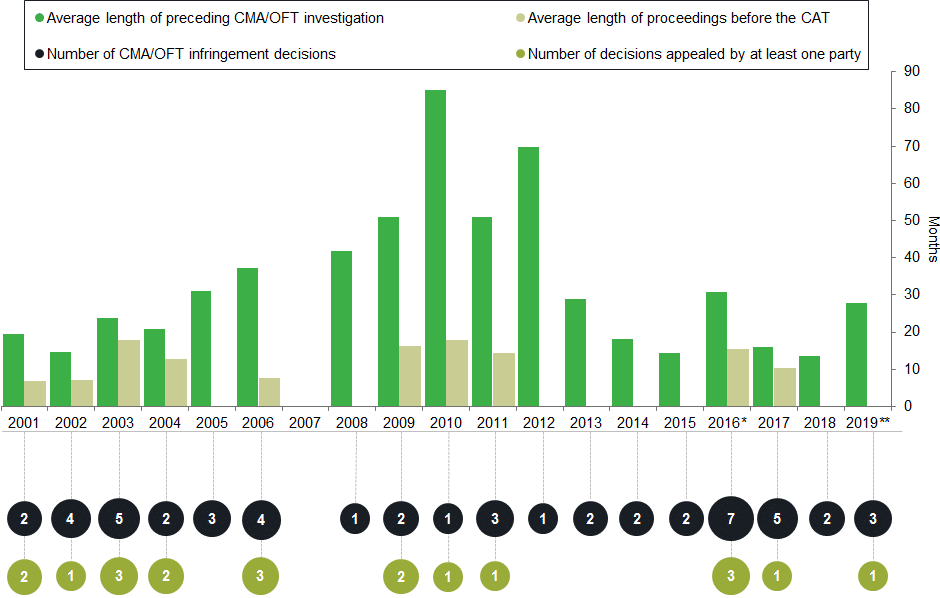

Firstly, not all competition infringement decisions result in appeals. Focusing purely on infringement decisions taken by the OFT and CMA, as opposed to those by sector regulators, there have so far been 51 infringement decisions in 137 separate cases.10 Only 20 of these, or 39%, have been appealed by at least one party, and the recent trend shows a downward trajectory: in the period from 2012 onwards, there have been appeals against only five infringement decisions out of 24 (21%),11 compared with 15 out of 27 (56%) in the years from 2001 to 2011.

Secondly, on the question of delay, analysis of all OFT and CMA infringement decisions that have resulted in appeals suggests a different picture from the one painted by the CMA. The problem is not the length of the appeal phase, still less the duration of the hearing: the issue is that the investigative phase is taking too long. On average, the period from the opening of the investigation to the date when the OFT or CMA adopted an infringement decision lasted approximately 29 months. The quickest was just over six months, in the case of Aberdeen Journals in 2002;12 the slowest was seven years and six months, in the Dairy case in 2011.13

By contrast, the average end-to-end period between lodging an appeal and the delivery of judgment14 at the CAT stage was under half this (12 months), with the quickest taking just under five months (Stock check pads),15 and the slowest concluded case taking 24 months (Toys and Games).16 Paroxetine took 23 months, albeit this case is still ongoing.17

The position is illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Duration and number of OFT/CMA and CAT cases

Source: Cases (whether at the OFT/CMA or on appeal) have been attributed to the year in which the initial infringement decision was adopted. See: https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases; https://www.catribunal.org.uk/cases.

The fact that some cases have been appealed further, beyond the CAT, necessarily adds to the overall delay, but that risk would arise even if appeals were determined on a judicial review or statutory ‘specified grounds’ standard, and there is no guarantee that the process in such cases would be any quicker.18

Are appeal hearings taking too long?

The short answer to this question is ‘no’. The average length of the substantive appeal hearings in relation to all OFT/CMA infringement decisions was approximately six days (the average length of hearing per appellant being 3.5 days),19 with a number of cases being heard in just one day, and the longest hearing (in 2010) lasting for 29 days (Tobacco).20 There is only one such case in which the duration of the substantive hearing before the CAT exceeded 20 days (Tobacco), so Lord Tyrie’s claim21 that ‘hearings on a single appeal often last four weeks or more’ is not borne out by the data.22

What about the Jarndyce v. Jarndyce analogy in the case of Phenytoin? The CMA’s controversial finding of an excessive pricing abuse was quashed on appeal by the CAT because the CMA was found to have made an error of law. The result could have been the same even if the appeal had been assessed against a judicial review or ‘specified grounds’ standard. At the time of writing, the litigation remains unresolved because the CMA has appealed the CAT’s decision to the Court of Appeal.

Moreover, there appears to be no clear link between hearing duration and overall length of appeal proceedings. The appeal phase before the CAT in Tobacco (where the hearing took 29 days) lasted 18 months, not significantly longer than in Construction,23 where the hearings for each appellant generally lasted between one and three days (albeit some involved multiple appellants) and the longest hearing took five days.

Is bringing an appeal a one-way bet?

The suggestion that bringing an appeal tends to result in reductions in fines (in some cases over 80%, according to Lord Tyrie)24 is distorted by the fact that the CAT made substantial reductions to the OFT’s fines in the Construction appeals, disagreeing with the OFT’s assessment of the seriousness of ‘simple’ cover pricing, and with the OFT’s use of a controversial ‘deterrence multiplier’ to increase the basic amount of the fine. Likewise, in Tobacco the OFT eventually abandoned its appeal, resulting in the fines being quashed in their entirety. But if the history of appeals suggests that many companies have been successful in having their fines reduced, as a legal matter, bringing an appeal is not a one-way bet. The CAT has the power to vary penalties, and this includes increasing as well as reducing them;25 in the Replica Football Kit26 appeal it exercised this power, increasing the penalty on one of the appellants (Allsports) by £70,000.27

Is the case for reform made out?

In circumstances where the stakes for being found to have infringed competition law are high (and will be even more so if the CMA is granted the power to impose fines on individuals), the ability to contest those findings on the merits before an independent judicial tribunal is a fundamental constitutional right and one that should be jealously safeguarded. Many of the cases that end up in the CAT involve complex and nuanced issues of fact, law and economics; some involve novel theories of harm, and others seek to extend the frontiers of the case law in areas that are relatively undeveloped and untested. Intrusive judicial oversight is a necessary counterweight to the broad exercise of administrative discretion. Not only has the CMA not made out a convincing case for change, but even the change in the standard of review that it is proposing would not address the fundamental problem, which is the excessive duration of many of the CMA’s investigations.

1 That is, an appeal in which the correctness of the CMA decision can be examined.

2 Letter from The Rt Hon Lord Tyrie to Secretary of State The Rt Hon Greg Clark MP, 21 February 2019 (the ‘Tyrie Letter’).

3 Tyrie Letter, p. 36, footnote 63.

4 Tyrie Letter, p. 35.

5 Tyrie Letter, p. 35, footnote 59, citing National Audit Office report (2016), ‘The UK competition regime’, February, para. 2.15.

6 Tyrie Letter, p. 39.

7 Tyrie, A. (2019), ‘Is competition enough? Competition for consumers, on behalf of consumers’, speech to the Social Market Foundation, 8 May.

8 Grenfell, M. (2019), ‘UK Competition Law enforcement: the post-Brexit future’, speech at City & Financial Global “Future of UK Competition Law” summit’, 11 June.

9 Tyrie Letter, p. 37.

10 Figures are stated as at 9 January 2020 (including Aberdeen Journals, where the OFT issued a second infringement decision after its first decision was quashed on appeal), based on all open and closed Competition Act 1998 and civil cartel cases listed at: https://www.gov.uk/cma-cases. Decisions involving multiple defendants in the same case have been counted as a single decision for these purposes. Proceedings in three of these cases (Case CE/9531-11, Paroxetine; Case CE/9742-13, Phenytoin; and Case 50299, Supply of products to the construction industry (pre-cast concrete drainage products) are ongoing.

11 The five decisions are those in the following cases: Case CE/9531-11, Paroxetine; Case CE/9742-13, Phenytoin; Case CE/9691-12, Galvanised steel tanks for water storage; Case 50230, Online sales ban in the golf equipment sector; and Case 50299, Supply of products to the construction industry (pre-cast concrete drainage products).

12 Case CE/1217-02, Aberdeen Journals Ltd. An earlier decision in Case CF/99/1200/E was quashed on appeal.

13 Case CE/3094-03, Dairy retail price initiatives.

14 Calculations are based on the date on which the CAT issued its judgment on liability or, if at a later date, on penalty. Purely procedural hearings (e.g. case management or relating to costs) are excluded. For Tesco’s appeal against the OFT’s decision in Dairy retail price initiatives, the date used is the date on which the CAT issued its judgment on liability, given that the issue of penalty was resolved between Tesco and the OFT, by way of consent order, two months later (Tesco Stores Ltd and others v. OFT [2012] CAT 31). For Double Quick Supplyline’s appeal against the OFT’s decision in Case CE/2464-03, Dessicant, which was resolved without a substantive hearing, by way of a consent order, the date used is the date of the consent order. For Genzyme’s appeal against the OFT’s decision in Case CP/0488-01, Exclusionary behaviour by Genzyme Ltd, the date used is the date on which judgment on liability was handed down. In that case, following the judgment on liability (Genzyme Ltd v. OFT [2004] CAT 4), the proceedings were adjourned to enable Genzyme and the OFT to reach an agreement on remedy. In the event, no agreement between the parties was forthcoming and the CAT issued a judgment on remedy 18 months later (Genzyme Ltd v. OFT [2005] CAT 32).

15 Case CE/3861-04, Stock check pads; Achilles Paper Group Ltd v. OFT [2006] CAT 24.

16 Cases CP/0239-01 and CP/0480-01, Toys and Games; the judgment on liability was issued after 20 months, but the judgment on penalty was delivered some 4.5 months later—see Argos Ltd and Littlewoods Ltd v. OFT [2005] CAT 13.

17 In the Paroxetine case the CAT issued its initial judgment some 23 months after the appeal proceedings were commenced, but then referred a number of questions to the Court of Justice. In Phenytoin, the CAT’s judgment was issued 16 months after the lodging of the appeal; that judgment is now under appeal by the CMA. The appeal by FP McCann Ltd in Supply of products to the construction industry (pre-cast concrete drainage products) is at a very early stage, having been lodged on 20 December 2019.

18 A period of around 6–11 months for appeals in market investigation cases (which are decided on judicial review grounds) is not unusual.

19 Figures exclude the appeal launched by Double Quick Supplyline Limited against the OFT’s decision in Dessicant, which was resolved without a substantive hearing, by way of a consent order.

20 Case CE/2596-03, Tobacco; Imperial Tobacco Group plc & others v. OFT [2011] CAT 41.

21 Tyrie Letter, p. 35.

22 The Tyrie Letter notes (page 38) that the Royal Mail appeal against an Ofcom decision was listed for five weeks; in the end, however, the hearing in that case lasted only 19 days. See Royal Mail plc v. Office of Communications [2019] CAT 27.

23 Case CE/4327-04, Bid rigging in the construction industry in England.

24 Tyrie Letter, p. 39.

25 Competition Act 1998, Schedule 8, para. 3(2)(b).

26 Case CP/0871/01, Price-fixing of Replica Football Kit.

27 Umbro Holdings Ltd & others v. OFT [2005] CAT 22.

Download

Contact

Dr Gunnar Niels

Managing PartnerGuest author

Mark Friend

Partner, Allen & Overy LLP

Contributor

Related

Download

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More