Practical guidance on the new state aid rules on public recapitalisations

On 8 May 2020, the European Commission introduced new state aid rules to tackle the effects of the crisis by extending the Temporary state aid Framework. Under specific conditions, member states can provide aid in the form of subordinated debt, hybrid capital and equity in line with state aid rules to companies facing difficulties due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The new state aid rules come with various measures designed to limit distortions to competition and trade. This article provides an overview of these new measures and discusses the important role of economic and financial analysis in evaluating and applying these tools.

A brief recap since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commission has approved approximately €2.5tn of state aid.1 So far, the majority of the notified aid measures have been approved to address companies’ urgent liquidity needs under the Commission’s Temporary Framework, which was introduced on 19 March 2020.2 The Temporary Framework sits alongside state aid tools available to member states to tackle the longer-term impact of the crisis, including aid for compensation for damages directly caused by the pandemic and restructuring aid.3 As the crisis continues, it is possible that companies’ temporary liquidity issues will turn into longer-term solvency issues. To avoid a large number of otherwise viable companies becoming insolvent, it is likely that more state support will be required over the coming months.

On 8 May 2020, the Commission extended the Temporary Framework to allow member states to provide aid in the form of subordinated debt, equity injections and/or hybrid capital to companies facing financial difficulties due to the ongoing crisis.4

This article discusses these new measures and the requirements under the Temporary Framework, focusing on the role of economic and financial evidence in assessing whether providing aid represents the best course of action, and if so, whether the aid is provided in line with state aid rules.

What are the new state aid rules under the extended Temporary Framework?

Under the extended Temporary Framework, member states can now provide aid to companies in difficulty due to the pandemic in the form of subordinated debt, equity injections and hybrid capital instruments, subject to a number of requirements being met.

Hybrid capital contributions and equity injections are particularly helpful for companies that are not able to take on more debt and where short-term liquidity support provided by the state is insufficient to ensure their long-term viability. Similarly, subordinated debt might enable companies that lack sufficient assets that can be offered as collateral to raise further funding.

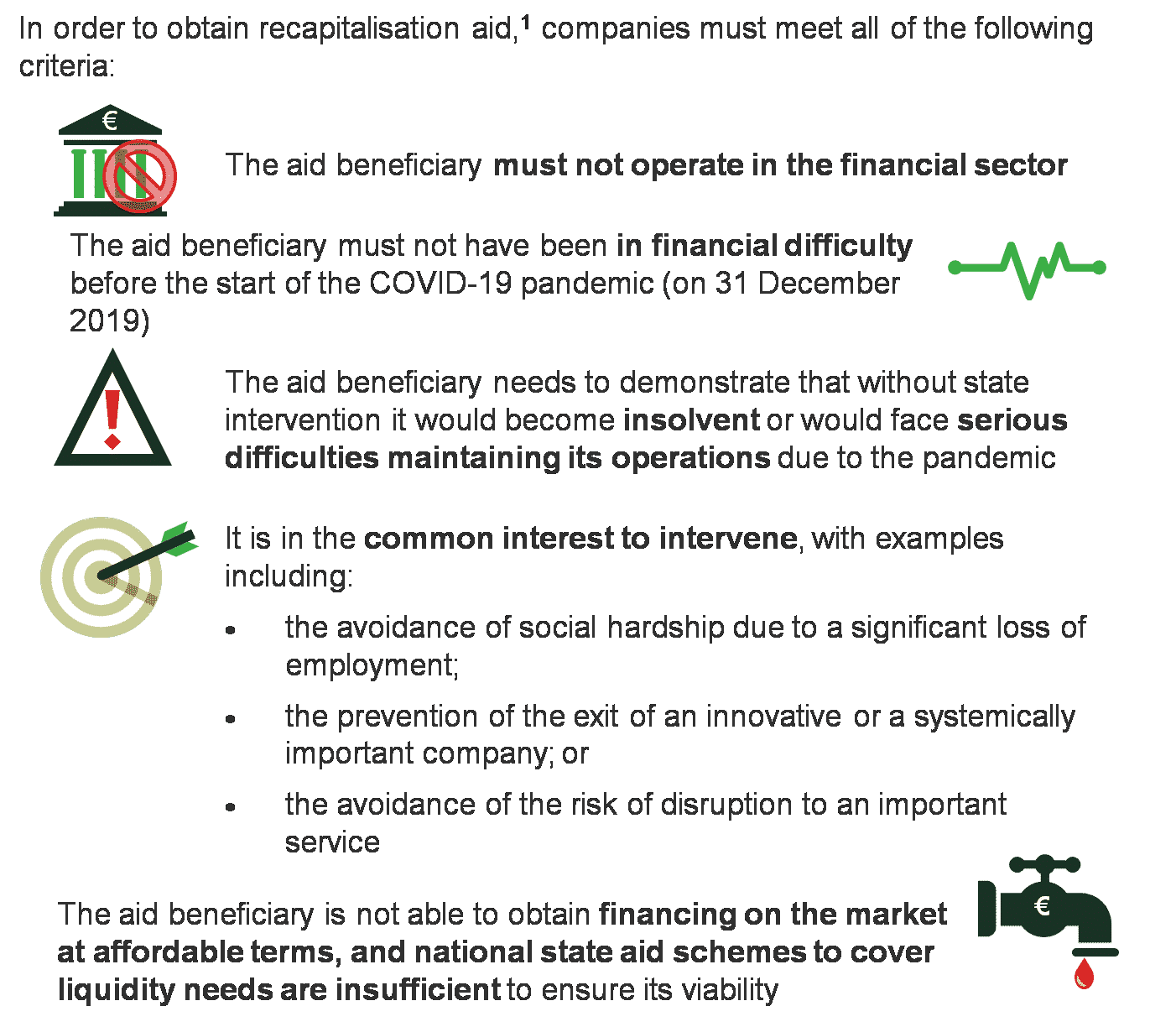

In order for companies to be eligible for these aid measures, they must meet all of the criteria set out in Figure 1.

Figure 1 What are the eligibility criteria for the aid measures?

Source: European Commission (2020), ‘Communication from the Commission – Amendment to the Temporary Framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak’, 8 May.

How to ensure that the aid is limited to the minimum necessary?

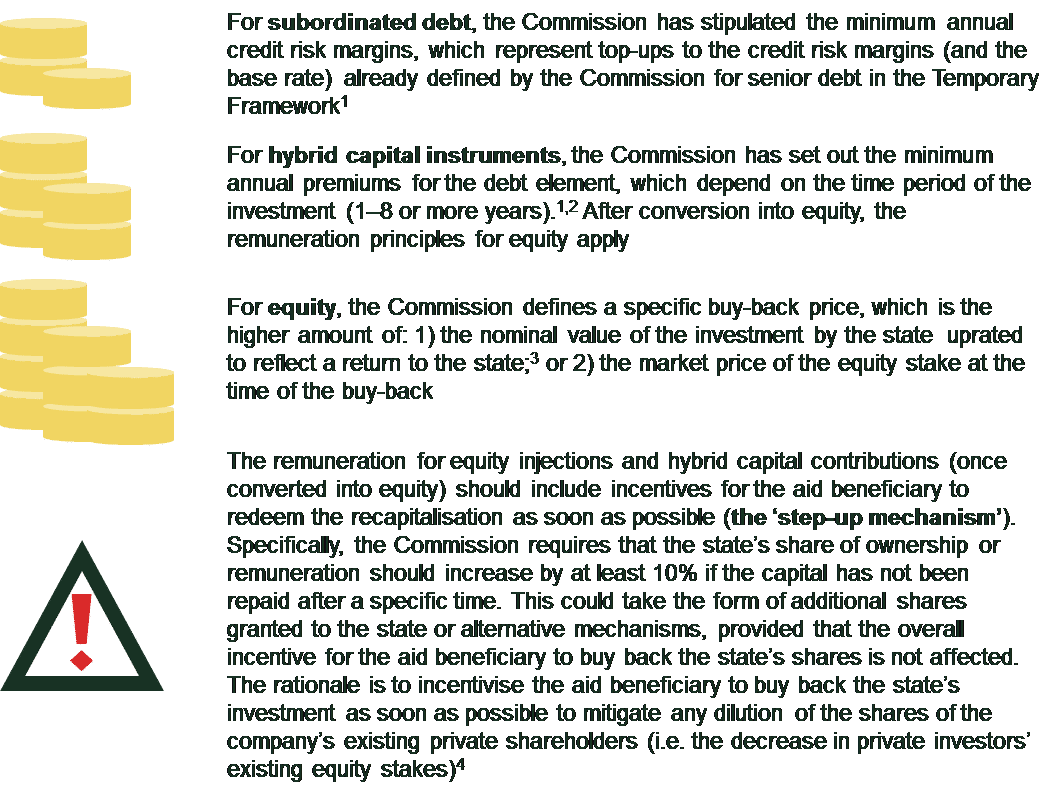

The recapitalisation aid measures should not exceed the minimum needed to ensure the viability of the beneficiary, and should not go beyond restoring the capital structure of the beneficiary before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, the state should receive remuneration as close to market terms as possible to reduce the potential for distortions to competition.

In particular, the Commission has set out the minimum required remuneration for the various aid instruments (see Figure 2). The required remuneration varies according to whether the recipient is a small-to-medium-sized enterprise (SME) or a large enterprise and the time horizon of the aid, but does not depend directly on the beneficiary’s financial and business risk.

Figure 2 What is the required minimum remuneration for each aid instrument?

Source: European Commission (2020), ‘Communication from the Commission – Amendment to the Temporary Framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak’, 8 May.

What measures are required by the Commission to limit distortions to competition and trade?

As the Commission considers that recapitalisation aid measures (i.e. aid in the form of equity and hybrid capital) are distortive for competition, the following requirements are imposed on aid beneficiaries.5

- Aid beneficiaries are prohibited from making dividend payments and share repurchases until the recapitalisation from the state has been redeemed in full.

- If 75% or more of the recapitalisation from the state is outstanding, companies are not allowed to make bonus payments to management.

- Large companies face restrictions on merger and acquisition activities, as they are prevented from acquiring more than a 10% stake in competitors or other operators upstream or downstream in the same line of business. The only exception allowed by the Commission is if the acquisition is necessary to maintain the viability of an aid beneficiary.

- If the aid beneficiary has significant market power and receives more than €250m of aid, additional ‘structural or behavioural’ measures need to be implemented to preserve competition in the affected markets.

Member states are required to submit a detailed exit strategy to the Commission when they acquire more than 25% of the beneficiary’s equity.6 If the state still holds more than 15% of the company’s equity six years after the intervention, a restructuring plan needs to be submitted to the Commission, demonstrating how the company expects to return to viability without further aid.7

The role of economic and financial analysis

Economic and financial analysis can help companies and member states to carefully assess the pros and cons of relying on such aid measures, in light of the stringent conditions placed by the Commission on receiving such aid. Furthermore, such analysis can help to ensure that the aid measures are in line with state aid rules under the Temporary Framework.8

Evaluate all the options first

As recapitalisation aid measures should only be used as a last resort, aid applicants should demonstrate that it would not be possible to obtain financing from the market on affordable terms. For example, an equity injection from the state might be justified if taking on more debt would lead to the company’s financial indicators (e.g. interest coverage ratio or the debt service coverage ratio) falling below acceptable levels and/or the company breaching the financial covenants of its existing debt. Therefore, financial analysis that explores different scenarios could help companies to evaluate all the options before opting for state recapitalisation measures. Although this is not explicitly introduced in the Temporary Framework, the aid beneficiary might also be required to demonstrate that options to raise new equity from existing shareholders and/or to write down debt from existing creditors have been explored to ensure that the aid is indeed limited to the minimum necessary.

As set out in Figure 3 below, before proceeding with any recapitalisation aid measures, given that such measures come with strict conditions, it would be important to check in advance if the capital from public entities could be structured on a no-aid basis (i.e. in line with the market economy operator principle, MEOP).

Figure 3 The importance of undertaking an MEOP test

The first step to receiving aid: assessing your eligibility

Was the company in financial difficulty before 31 December 2019?

As is generally the case under the Temporary Framework, in order to be eligible for aid, companies should provide evidence that they were not in financial difficulty as of 31 December 2019. Under the approach followed by the Commission, this requires an assessment of the company’s debt-to-equity ratio and other financial indicators, among other elements.9 However, in practice, companies’ financial accounts are unlikely to have been finalised at the end of 2019. Therefore, aid applicants may need to rely upon alternative documentation (e.g. quarterly or half-year financial statements) to assess whether they would qualify for aid under the Temporary Framework.

What would happen in a ‘but-for’ world?

In order to be eligible for the aid, a counterfactual scenario would need to be prepared to demonstrate that the company would become insolvent or face difficulties maintaining its operations if the recapitalisation aid measure was not granted. In this regard, companies need to provide robust financial evidence on the extent to which the company is already suffering, or is likely to suffer, from solvency issues due to the pandemic. This analysis could be based on forecasts of the company’s debt-to-equity ratio or similar indicators.

In addition, the company might be required to demonstrate the causal link between the pandemic and the financial difficulties it has suffered. If the reduction in demand is due not only to the pandemic but also to other factors present before the start of the pandemic, economic analysis can help to disentangle the various effects leading to the financial difficulties.

The goal of the aid should be to get the company back on its feet

The beneficiary also needs to demonstrate that it will be likely to return to financial viability if the aid is granted. This could involve assessing whether the company would be able to achieve a ‘reasonable profit’ in the medium term to facilitate the exit of the state, taking into account sector- and company-specific factors. The assessment would also need to ensure that the aid does not go beyond restoring the capital position of the aid beneficiary prior to the start of the pandemic (e.g. comparing the value of financial indicators as of December 2019 with the value at the time when the beneficiary applied for aid).

Overall, this exercise requires developing a robust business plan that would stand up to scrutiny by the Commission. The appropriateness of key assumptions, such as trends in operating profit and the drivers of profitability, should be based on robust evidence (e.g. sector- or company-specific forecasts prepared after the start of the pandemic). In addition, economic modelling can be applied to estimate core input parameters, such as the recovery period over which demand returns to pre-crisis levels.

As outlined below, developing such a business plan is particularly important for cases where the Commission requires the beneficiary to submit a detailed plan about how and when exactly the state will be repaid (the ‘exit strategy’).

Planning the state’s exit strategy

The Temporary Framework stipulates that if the state acquires more than 25% of the beneficiary’s equity,10 an exit plan needs to be submitted to the Commission. In particular, the exit plan should demonstrate that the state’s equity share will be reduced to 15% or lower over a period of six years—as otherwise a restructuring plan would need to be submitted.

The exit plan should also take into account the required step-up mechanism for the state’s remuneration, either in the form of an increase in the state’s ownership or its remuneration over the period of its investment. It might be necessary to develop estimates of the company’s value at the time of the state’s expected exit to assess the price that the aid beneficiary would have to pay, and if this would be affordable for the company.

Developing such an exit plan can be particularly challenging if the company receives hybrid capital, as the nature of such instruments varies significantly. The pricing methodologies that underpin the assumptions in the exit plan regarding the state’s remuneration should take into account the different options that are embedded in a hybrid instrument. For example, some convertible loans can be converted at the state’s discretion at any time, while other convertible loans can only be converted at set dates. Flexible option modelling tools could be used to analyse the value embedded in these terms in order to derive a market price for these types of instruments.

Restructuring aid—the real last resort?

If the state’s equity share is not expected to be reduced to 15% or less over a six-year period, a restructuring plan needs to be submitted to the Commission. In principle, if the exit plan is based on sufficiently robust assumptions, the likelihood of needing recapitalisation aid further down the line should be limited. However, unforeseeable events after receipt of the recapitalisation aid could lead to a further deterioration of the company’s financial position, which might require additional restructuring aid.

The restructuring plan should set out how the company expects to return to long-term viability without the aid within a reasonable timeframe.11 Similar to the exit plan, the Commission is likely to check the appropriateness of key assumptions, including the likelihood that the company is able to achieve a reasonable level of profitability in the medium to long term, even if certain downside scenarios materialise. The Commission will also assess whether the planned restructuring measures are in line with the EU’s environmental and digital objectives.12

Special requirements for integrated companies—watch out for potential leakages

The Commission requires that companies that receive recapitalisation aid should put in place clear accounting separation requirements to show that the aid does not leak into other entities of the corporate group that were already in financial difficulty on 31 December 2019. It would therefore be important to ensure that accounting mechanisms are in place to prevent the leakage of aid, and that transactions between the different entities are on an arm’s-length basis. The arm’s-length nature of transactions within the corporate group could be established through an analysis of the associated costs and/or based on evidence from similar transactions between independent companies.

Drawing the market boundaries and assessing market power

If the beneficiary of a recapitalisation aid measure above €250m holds significant market power (SMP), member states must propose additional measures to preserve effective competition in those markets. In the aviation sector, for example, this could include selling airport slots or committing to ‘freeze’ frequencies on certain routes.13

Before designing such measures, it would be necessary to undertake an economic analysis of the degree of the aid beneficiary’s market power. This involves defining the relevant product and geographical market(s), based on an empirical analysis of the degree of demand- and supply-side substitutability between the products and services, and geographic areas offered and served by the aid beneficiary and those offered and served by competitors.

Once the boundaries of the relevant market have been defined, it will be possible to identify the firms that compete, including the aid beneficiary, and, in turn, to assess whether the latter holds SMP by examining a number of aspects, including market shares, barriers to entry and expansion, and countervailing buyer power.

Think ahead of the game when it comes to mergers

Under the state aid rules set out in the Temporary Framework, large companies face restrictions on merger and acquisition activities, as they are prevented from buying more than a 10% stake in companies operating in the same line of business.

The Commission can allow an aid beneficiary to acquire more than a 10% stake in a company in the same line of business, provided that the acquisition is necessary to maintain the beneficiary’s viability. For example, if the target is an important supplier of the aid beneficiary, the latter may need to demonstrate that in the absence of the merger, the costs that the company would incur to obtain the same inputs from an alternative supplier would be sufficiently high to force the beneficiary out of business.

Besides, it should be considered that such transactions are subject to the Commission’s merger control, where applicable. This would require the merging parties to prepare a robust economic case, highlighting the extent to which the negative effects of the merger on competition are expected to be offset by merger-specific efficiencies. This analysis needs to be undertaken separately from the state aid aspects involved in the recapitalisation aid measure.

In light of the strings attached by the Commission when it comes to M&A activity, it will be important for aid beneficiaries to draw up a clear strategy before committing to recapitalisation aid measures. Inorganic growth, as opposed to a state recapitalisation, could represent a reasonable option to consider given the current market conditions (assuming that funds are available and/or the company is capable of attracting private investors). By the same token, the prospect of being acquired by another company may also need to be carefully assessed, as that might leave the target company better off compared to a state recapitalisation.

When the going gets tough, the tough count to ten

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Commission has approved an unprecedented amount of state aid in a very short period to address the short-term liquidity needs of companies. The new recapitalisation aid measures introduced by the Commission aim to tackle the longer-term impact of the crisis, together with aid to compensate for damages directly caused by the pandemic and restructuring aid. However, the Commission attached many conditions to the new recapitalisation aid measures to limit potential distortions of competition.

Financial and economic analysis plays a critical role in helping companies assess their eligibility for, as well as the compatibility of, the new measures. More importantly, however, such analysis should also be used to weigh the pros and cons of accepting the restrictions that come with the aid, and to assess whether alternative options exist that involve no aid—and, as such, no strings attached.

1 Oxera analysis, based on European Commission (2000), ‘State aid rules and coronavirus’, https://ec.europa.eu/competition/state_aid/what_is_new/COVID_19.html, accessed 4 May, supplemented by information in the public domain from the relevant national authorities.

2 European Commission (2020), ‘Temporary Framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak’, 19 March.

3 For details, see Oxera (2020), ‘A practical guide to the state aid rules to tackle the impact of COVID-19’, April.

4 Companies can apply for aid until June 2021. See European Commission (2020), ‘Communication from the Commission – Amendment to the Temporary Framework for State aid measures to support the economy in the current COVID-19 outbreak’, 8 May.

5 The Commission does not require aid in the form of subordinated debt to be accompanied by measures to limit the impact on competition and trade unless the amount of the subordinated debt exceeds (i) two thirds of the annual wage bill of the beneficiary (for SMEs: the annual wage bill) and (ii) 8.4% of the beneficiary’s total turnover in 2019 (for SMEs: 12.5%).

6 This is only applicable to large companies.

7 The restructuring plan needs to be developed in line with the Commission’s Rescuing and Restructuring Guidelines.

8 Aid measures that exceed €250m under the Temporary Framework must be notified individually to the Commission.

9 The definition for an undertaking in difficulty is set out in European Commission (2014), ‘Commission Regulation (EU) No 651/2014 of 17 June 2014 declaring certain categories of aid compatible with the internal market in application of Articles 107 and 108 of the Treaty Text with EEA relevance’, L 187/1, Official Journal of the European Union, 26 June, Article 2, para. 18.

10 Only applicable to large companies.

11 The restructuring plan should be developed in line with the Commission’s Rescuing and Restructuring Guidelines.

12 This contrasts with large recapitalisation measures (i.e. when the state acquires more than 25% of the ownership in a large company). In such instances, it is only necessary to report to the Commission the contribution of the aid to the EU’s green and digital objectives.

13 For example, see European Commission (2019), ‘CASE M.3280 – Air France/KLM’, 6 February.

Download

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More