To mothball or not to mothball?

The current power generation shift from carbon-intensive energy sources towards carbon-neutral, intermittent sources such as wind and solar continues to be a priority throughout the EU. This transition has consequences for the efficient design of power markets. Jan Bouckaert, Oxera Associate and Professor of Economics at the University of Antwerp, and Geert Van Moer, PhD Fellow of the Flanders Research Foundation, and University of Antwerp, discuss recent research on the implications for investments in conventional power plants.

The transition away from reliable base-load (e.g. coal and nuclear) and dispatchable (e.g. gas) energy sources and towards intermittent technologies has consequences for the efficient design of power markets. It is possible that the transition will be accompanied by a shift towards a market that relies on capacity remuneration mechanisms to guarantee security of supply.

This article discusses the consequences of the introduction of intermittent power generation and the implications for investments in conventional power plants. In particular, it highlights that security of supply measures motivated by the low profitability of dispatchable plants underestimate firms’ strategic motivations to install underused dispatchable units.

What are the consequences of the introduction of intermittent power generation?

A typical characteristic of renewable energy sources, such as wind or solar, is their intermittent nature. The ability to generate power from these sources depends on the necessary wind speed or sunlight, which are outside the control of the supplier. At least two consequences have resulted from the introduction of intermittent power generation.

- First, it has increased the need for dispatchable back-up facilities to secure the power supply. For example, in 2010 the New York Independent System Operator assessed that the addition of 1 MW of wind removes only 0.2–0.3 MW of existing dispatchable resources needed to meet the reserve requirements.1

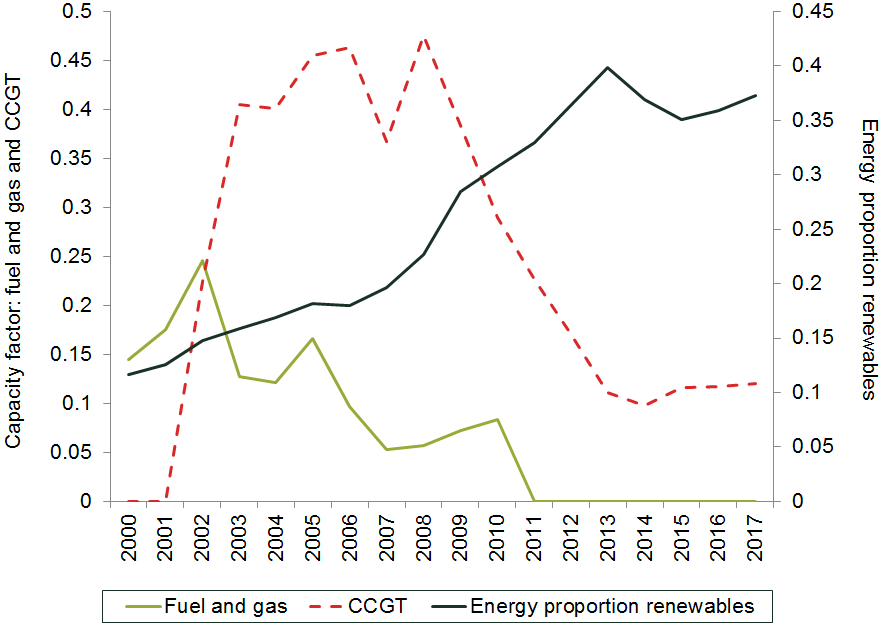

- Second, intermittent energy sources typically have low to zero marginal generation costs and have often enjoyed priority of dispatch. As a consequence, the residual load profiles of conventional dispatchable power plants have decreased considerably, leading to a reduction in the plants’ profitability. Spain, where windmills and photovoltaic solar panels generate 25% of electricity consumed, provides a good example of this phenomenon. Figure 1 illustrates that the ratio of actual to potential generation (i.e. the capacity factor) of Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT) plants in Spain declined from 40% in 2004 to 11% in 2017, and declined even further for fuel and gas plants over the same period.2

Figure 1 The capacity factor of CCGTs in Spain, 2000–17

Similarly, in Denmark, another frontrunner in intermittent power, wind farms generated 38% of total electricity consumption during 2016 at the expense of conventional power plants.3

The drop in plant profitability has led firms to reconsider maintaining the operations of their dispatchable plants. During 2012 and 2013, major utilities planned or actually closed 20 GW of CCGT capacity in the EU.4 Accordingly, public interventions, such as capacity payments, have been proposed or implemented (subject to state aid approval) to guarantee sufficient returns from the capacity needed to secure power supply.5 For instance, in the UK, payments amount to £2.2 per MW per hour for capacity to be delivered in 2018 and beyond.6 In the North East of the USA, capacity payments required to maintain the security of supply have been estimated to be $6.87 per MW of capacity per hour in 2018/19.7

What are the consequences of the reduction in the residual load profiles of conventional power plants?

The direct effect of low residual load profiles of conventional power plants is a reduction of profitability at the plant level, which can undermine firms’ incentives to maintain or invest in dispatchable units.

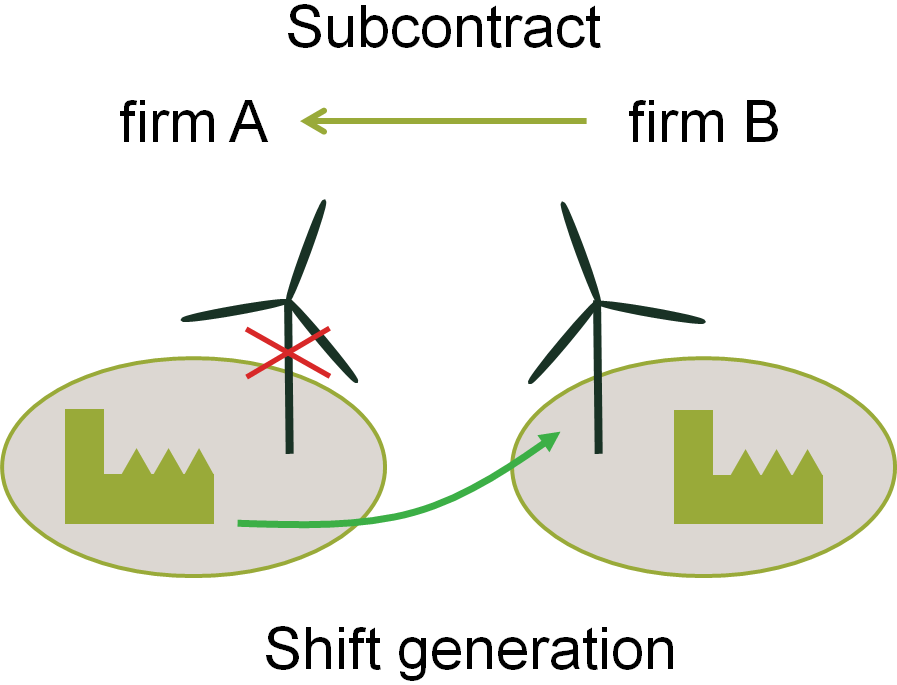

Despite the low profitability at the plant level, recent research has shown that there is also an indirect, opposite effect that favours investments at the level of the firm.8 Before the introduction of carbon-neutral intermittent power, firms decided whether to diversify their power sources following a non-strategic, cost-optimised trade-off between fixed costs and variable costs. That is, base-load plants with a high fixed-cost base run at the lowest variable cost, whereas small, low fixed-cost peak plants are dispatched only when needed, as a result of their high variable costs. In a world where intermittent power sources represent a significant proportion of total energy provision, power-generating companies have strategic incentives to install or maintain underused dispatchable units such as gas-fired plants. Consider the simple example in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Subcontracts with intermittent power generation

The figure illustrates two firms, A and B, each equipped with a dispatchable technology (i.e. a conventional plant) and an intermittent technology (i.e. a wind farm). Both firms have contracted in advance how much power they will sell. Since weather conditions are location-specific, not all intermittent units are always available. For example, the weather conditions where firm B is located could lead to an abundance of wind, while at the same time, conditions where its competitor, firm A, is located could mean that the firm is short of wind and needs to rely on its expensive dispatchable units.

In such a framework, competing firms can gain from horizontal subcontracting as follows. The (prime) contractor, instead of activating its expensive gas-fired plants, purchases low-cost power from its competitor’s (the subcontractor’s) intermittent units. If firm A cannot generate power from its intermittent source, and only has access to its dispatchable units, its willingness to pay for outsourcing to firm B equals at most just less than its cost of in-house dispatchable generation. Accordingly, the mere ability to dispatch conventional coal- or gas-fired plants credibly puts an upper bound on the contracting cost.

As a result, dispatchable units, even if they are never used for power generation, serve as credible protection against hold-up and reduce contracting costs. An indicator of plant profitability, such as the capacity factor, is therefore insufficient to assess a firm’s returns from investing in a dispatchable portfolio that complements its intermittent portfolio. From a policy perspective, there are indirect returns from dispatchable units at the level of the firm. These indirect returns favour investments and contribute to the public good problem of securing supply. They should accordingly be taken into account, for example, when countries choose whether and how to implement capacity payment mechanisms.

Horizontal subcontracting or outsourcing between power-generating firms typically takes place close to delivery, for example on a day-ahead or intraday market, after firms have undertaken long-term delivery commitments with their end-customers or downstream retailers. This physical trading between competing firms is already gaining significance because intermittent power generation, which is growing, is imperfectly correlated. Indeed, Monforti, Gaetani and Vignati (2016) analyse the synchronicity of wind power production in a number of EU member states compared with the EU average.9 They show that wind power production in peripheral countries is less correlated with the rest of the EU as compared with central European countries. In 2012, around two-thirds of the power traded on Elbas, an important European intraday market, crossed borders.10

Conclusions

Today, policy choices often favour low-carbon (intermittent) sources such as wind and solar. These sources have enjoyed dispatch priority or extensive subsidies, for example. As a result, conventional units have moved up the dispatch curve (i.e. become more expensive relative to the low-carbon sources).11 For example, gas-fired plants operate fewer hours and may be mothballed due to their high maintenance costs.

At the same time, however, these policies encourage firms to shift generation from dispatchable units towards intermittent units by outsourcing generation through horizontal subcontracting. Gas-fired plants then serve an important strategic purpose. Firms that are equipped with inexpensive dispatchable generation are favoured, as they attain the best subcontracting terms.

These insights offer a framework to analyse generators’ investment incentives as they increasingly come to rely on intermittent power sources.12 From this perspective, there is an important distinction between profitability at the firm level and profitability at the plant level. Firms benefit from having dispatchable facilities that operate few or even zero hours per year, as it limits the contracting costs paid to competitors.13 Thus, the revenues generated by peaking plants need not cover the investment and variable costs. Plant profitability is not a necessary condition for profit maximisation, as a firm can maximise its profits by holding idle generation capacity.14

Rather than closing down gas-fired plants, it may therefore be necessary (although not sufficient) to provide only a few hours of operation. Mothballing is not all about capacity factors.

Jan Bouckaert and Geert Van Moer

1 New York Independent System Operator (2010), ‘Growing Wind—Final Report of the NYISO 2010 Wind Generation Study’, accessed 19 January 2018.

2 Red Eléctrica de España (2017), ‘Statistical series’, accessed 5 January 2018.

3 Energinet (2017), ‘Sustainable energy together’, Annual Report 2017.

4 Caldecott, B. and McDaniels, J. (2014), ‘Stranded generation assets: Implications for European capacity mechanisms, energy markets and climate policy’, Stranded Assets Programme Working Paper, accessed 19 January 2018.

5 The European Commission has recently concluded its first-ever sector inquiry in the state aid context, which investigated whether capacity payments comply with state aid rules. For further details, see European Commission (2016), ‘Final Report of the Sector Inquiry on Capacity Mechanisms’, report from the Commission, 30 November, pp. 8–9; and Oxera (2017), ‘Energy scarcity: arrivederci?’, Agenda, January.

6 National Grid (2014), ‘Provisional Auction Results’, accessed 19 January 2018.

7 PJM Interconnection (2015), ‘2018/2019 RPM Base Residual Auction Results’, accessed 19 January 2018.

8 Bouckaert, J. and Van Moer, G. (2017), ‘Horizontal subcontracting and investment in idle dispatchable power plants’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 52, pp. 307–332.

9 Monforti, F., Gaetani, M. and Vignati, E. (2016), ‘How synchronous is wind energy production among European countries?’, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 59, pp. 1622–1638.

10 Scharff, R. and Amelin, M. (2016), ‘Trading behaviour on the continuous intraday market Elbas’, Energy Policy, 88, pp. 544–557.

11 Joskow, P.L. (2011), ‘Comparing the costs of intermittent and dispatchable electricity generating technologies’, The American Economic Review; Papers and Proceedings, 100:3, pp. 238–241.

12 Ambec and Crampes (2012) study the optimal energy mix with reliable and intermittent energy sources. See Ambec, S. and Crampes, C. (2012), ‘Electricity provision with intermittent sources of energy’, Resource and Energy Economics, 34:3, pp. 319–336. Gowrisankaran et al. (2016) empirically assess the social cost of solar power generation in a setting of welfare maximisation based on Joskow and Tirole (2007). See Gowrisankaran, G., Reynolds, S.S. and Samano, M. (2016), ‘Intermittency and the value of renewable energy’, Journal of Political Economy, 124:4, pp. 1187–1234; and Joskow, P.L. and Tirole, J. (2007), ‘Reliability and competitive electricity markets’, The RAND Journal of Economics, 38:1, pp. 60–84. The authors disentangle the cost of unpredictability, the cost of varying availability and the installation cost, but do not consider market power. For further details on capacity payment mechanisms, see also Cramton, P. and Stoft, S. (2006), ‘The Convergence of Market Designs for Adequate Generating Capacity’, Report for California Electricity Oversight Board, accessed 19 January 2018; Joskow, P.L. (2006), ‘Competitive Electricity Markets and Investment in New Generating Capacity’, AEI-Brookings Joint Center Working Paper No. 06-14, accessed 15 January 2016; and Joskow, P.L. (2011), ‘Comparing the costs of intermittent and dispatchable electricity generating technologies’, The American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings, 100:3, pp. 238–241.

13 Lambin (2016) finds a strategic effect in the opposite direction by investigating mothballing—the practice of temporarily withdrawing generation capacity—as a predatory strategy. See Lambin, X. (2016), ‘Mothballing as a predatory strategy’, accessed 19 January 2018.

14 Several papers outline other reasons why firms can benefit from holding idle capacity. For instance, incumbent firms may be willing to install excess capacity in order to deter entry. See, for example, Dixit, A. (1979), ‘A model of duopoly suggesting a theory of entry barriers’, Bell Journal of Economics, 10:1, pp. 20–32. In a dynamic setting, Maskin and Tirole (1988) find that holding excess capacity can sustain collusion because it discourages competitors from triggering a price war. For further details, see Maskin, E. and Tirole, J. (1988), ‘A theory of dynamic oligopoly, II: Price competition, kinked demand curves, and Edgeworth cycles’, Econometrica, 56:3, pp. 571–599. We show that, in contrast, firms can sometimes increase profits by jointly divesting idle dispatchable units. See Bouckaert, J. and Van Moer, G. (2017), ‘Horizontal subcontracting and investment in idle dispatchable power plants’, International Journal of Industrial Organization, 52, pp. 307–332.

Download

Contact

Jostein Kristensen

PartnerGuest author

Geert Van Moer

Contributor

Related

Download

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More