Assessing state aid in the beautiful game

As the old saying goes: ‘football is a funny old game’. Indeed, some characteristics of football clubs create specific challenges when applying the standard state aid frameworks to assess whether measures constitute aid and whether any aid is in line with state aid rules.

Until 2013, there had been few state aid investigations into football clubs, but the landscape then changed significantly, with in-depth investigations being launched in Spain and the Netherlands. Following European Commission Decisions on these cases in 2016, we look at the challenges of applying the standard state aid framework to football clubs. Whether the number of football-related state aid cases will continue to increase remains to be seen, but these investigations highlight the importance of ensuring compliance with state aid rules

In July 2016, the European Commission concluded a number of in-depth state aid investigations into football clubs in Spain and the Netherlands.1 Measures granted by Dutch municipalities to five Dutch football clubs were all found either not to constitute aid or to constitute aid in line with EU state aid rules. In contrast, measures provided by Spanish authorities to seven Spanish football clubs were all found to constitute incompatible state aid, with the Commission ordering the clubs to repay the aid.

These Decisions follow a judgment in the UK courts in June 2014 involving a state aid allegation relating to financial assistance offered by Coventry City Council to the owner of the stadium used by Coventry City Football Club.2 Following financial difficulties experienced by the club, the Council restructured a bank loan to the stadium’s owner. In light of the Council’s significant shareholding in the stadium, and as the restructuring would help to protect the Council’s equity stake, the judge concluded that the restructuring of the loan did not constitute state aid.3

The Commission had previously approved a number of cases of aid following notifications in other member states in 2013 and 2014. These include the renovation of sport stadiums in the cities of Chemnitz, Erfurt and Jena in Germany; the construction and renovation of multifunctional football stadiums in the Belgian regions of Flanders and Brussels; the construction and renovation of nine stadiums for the 2016 European football championship in France; and the reconstruction of three sport stadiums in Belfast.4

As the old saying goes: ‘football is a funny old game’. Indeed, some characteristics of football clubs create specific challenges when applying the standard state aid frameworks to assess whether measures constitute aid, and whether any aid is in line with state aid rules. In this article, we summarise some of the recent Commission Decisions, set out the challenges in applying economic and financial analysis as part of standard state aid assessments in this sector, and discuss some of the implications of the Commission’s Decisions.5

Warm-up: what is state aid, and why do state aid rules apply to football clubs?

State aid is any economic advantage granted by public authorities through state resources on a selective basis to commercial undertakings that might distort competition and trade in the EU.6 The definition of state aid is broad, and can include measures ranging from direct grants to tax exemptions. In order to assess whether a measure from the state confers an economic advantage on the recipient, the market economy operator principle (‘MEOP’) can be used, as described in the box below.

The MEOP test

To determine whether transactions carried out by public authorities confer an economic advantage, the MEOP test assesses whether, under similar circumstances, a private operator would have behaved in a similar manner to the public authority. The test is typically applied through either of the following methods:

- benchmarking analysis—the terms and conditions of the transaction from the public authority are compared with similar transactions carried out by comparable private operators in similar situations;

- profitability analysis—the expected return from the transaction is compared with the return a private operator would require in similar situations.

Source: European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Notice on the notion of State aid as referred to in Article 107(1) of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union’, C 262/1, Official Journal of the European Union, 19 July, section 4.2.

Not all state aid is unlawful. If the aid contributes to a well-defined common interest objective, is appropriate as a policy instrument, is limited to the minimum necessary, and is targeted at market failures without having an undue negative impact on competition and trade, aid is considered lawful (i.e. ‘good’ or compatible aid).7 If the aid does not meet these criteria, it must be repaid (with interest) by the beneficiary to the relevant member state. State aid can become repayable up to ten years after the aid has been deemed to constitute existing aid.

In the same way as other entities engaging in economic activities, professional football clubs are subject to EU state aid rules because the sporting activities are of a commercial nature. Football clubs generate revenues via three main sources: ticket sales for matches, sale of broadcasting rights, and merchandising and sponsorship activities.

Arrangements between football clubs and government (including local authorities) are common, with around half of the stadiums of Europe’s top division clubs owned by the local municipality or by the state.8 As football clubs provide social and cultural roles in society, politics also plays a key role in funding decisions. Clubs such as Real Madrid C.F. and F.C. Barcelona represent the local identities of the regions of Castile and Catalonia respectively, with the teams’ respective performances being of high importance for the local regions.9 According to the President of the Government of the Catalonia region, ‘F.C. Barcelona, is an important ambassador for Catalonia, and its sovereignty.’10 The region’s push for independence makes the rivalry between Real Madrid C.F. and F.C. Barcelona as much of a clash of political perspectives since it is between two of the top football clubs in the world.

The whistle blows: round-up of recent action by the European Commission

In Spain, the Commission ordered the recovery of aid from seven clubs following investigations covering tax arrangements, the sale of land from the state to the club, and state guarantees on loan arrangements.

- Corporate tax rates—according to the Commission, the classification of Real Madrid C.F., F.C. Barcelona, Athletic Bilbao and Atlético Osasuna as non-profit organisations gave the clubs an unfair advantage in allowing them to pay a lower corporate tax rate.11

- Transfer of land—the Commission concluded that compensation received by Real Madrid C.F. from the City of Madrid to settle a dispute relating to the failure to transfer land in 1998 was overestimated by €18.4m.12

- State guarantees—according to the Commission, state guarantees on loan arrangements enabled Valencia C.F., Hercules and Elche C.F. to obtain loans on more favourable terms.13

The Commission also investigated measures granted by municipalities in the Netherlands to five Dutch clubs. In contrast to the investigations in Spain, the Commission concluded that the measures were either in line with the MEOP and therefore did not constitute aid, or constituted compatible aid.

- The Commission concluded that the sale and leaseback of land for PSV Eindhoven’s stadium and training block from the City of Eindhoven had been carried out on market terms (and so this did not constitute aid).14

- According to the Commission, arrangements between municipalities and F.C. Den Bosch, MVV Maastricht, NEC Nijmegen and Willem II constituted compatible aid, in line with the rescue and restructuring aid guidelines. The arrangements included compensation received by NEC Nijmegen for waiving its right to acquire the stadium from the municipality,15 the waiver of MVV Maastricht’s loan and the purchase of the stadium and training grounds by the municipality,16 the reduction in rent for Willem II’s stadium by the municipality,17 and the purchase of training facilities and a debt-to-equity swap between the municipality and F.C. Den Bosch.18

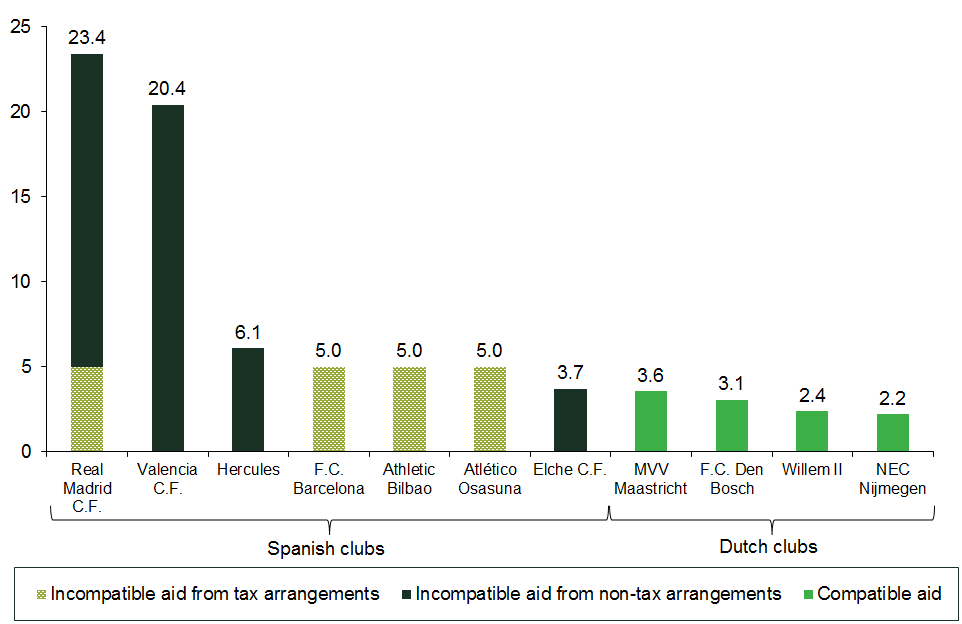

Based on the Commission Decisions described above, the Commission’s estimates of aid provided to each football club are summarised in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Overview of the Commission’s estimates of the aid provided to each football club (€m)

Sources: Oxera analysis, based on various Commission Decisions and press releases.

Tweaking the line-up: the challenges of applying the standard state aid framework to football clubs

The application of the standard state aid framework to football clubs in order to assess whether a measure from the state, such as a direct grant, loan, guarantee or an equity injection, is in line with the MEOP, or whether any aid is compatible with the applicable state aid rules, is not straightforward. When applying the standard state aid frameworks, it is important to take into account a number of specific characteristics of the industry, as discussed below.

Reasons for investing in football clubs

In most industries, investment decisions are profit-driven; however, for the reasons set out below, investment in football clubs is also motivated by non-financial factors. It is important to take these factors into consideration when applying the MEOP test in the football sector.

In contrast to the traditional objective of maximising shareholder returns, European football clubs tend to be driven by maximising on-field performance.19 Many clubs are owned by billionaires and/or large investment authorities, with Chelsea F.C. owned by Roman Abramovich, Manchester City F.C. owned by Sheikh Mansour, and Paris Saint–Germain F.C. owned by the Qatar Investment Authority.20 These investors have injected several millions into their club’s squad, brand and infrastructure.21

Evidence from empirical studies suggests that, in addition to financial factors, investors in football clubs pay significant attention to clubs’ on-field performance, league ranking, brand value, the size of the fan base and reputation.22

Indeed, there is evidence of investors paying significant amounts for equity stakes in football clubs, despite the book value of equity of the clubs being negative at the time of the transaction. As an illustration, Portsmouth F.C. and Birmingham City F.C. were sold in 2009 for €68.3m and €94.6m respectively, despite each club having a negative book value of equity at the time (of -€60.5m and -€2.6m respectively).23

Therefore, when assessing whether transactions are in line with the MEOP, it is important to consider clubs’ intangible assets, such as their brand value, reputation and fan base, in addition to the market value of football clubs’ key assets, and the cyclicality of clubs’ revenues, which are highly dependent on qualification for key tournaments, such as the Champions League.

The market value of football clubs’ key assets

For the purposes of the MEOP test, the approach to assessing the financial strength of football clubs should also take into account the market value of the club’s players. The market value of players can differ significantly from their book value (i.e. the value recorded on the financial statements, which reflects the amortisation of a player’s contract over time). Indeed, ‘Bayern Munich, FC Barcelona, Atlético Madrid and Juventus all have squads whose footballing worth is disproportionately high compared with their weight on the club’s financial accounts.’24 This arises as a result of clubs minimising transfer fees, or purchasing young players who are acquired cheaply as a result of their unproven record, but whose market value may become substantial over time.

As an illustration, the aggregated book value of F.C. Barcelona’s players, according to their 2015/16 accounts is €202m, compared with an estimated current market value of €767m.25 The club’s squad includes Lionel Messi, one of the most valuable players in the world, who was transferred to F.C. Barcelona’s junior team free of any transfer fee in 2000—while his current value is estimated to be in the region of €120m.26

For these reasons, any book-value-based approach may not appropriately capture the financial strength of football clubs.

Impact of qualification to the Champions League

In assessments of the profitability of football clubs, for the purposes of the MEOP test, it is also important to take into account the potential significant variability in football clubs’ revenues on a year-to-year basis, which is driven by performance in key tournaments. According to the chairman of Juventus F.C., football is ‘a sector traditionally characterised by a lack of equilibrium and great irregularity, in part due to the uncertainty of sports results’.27

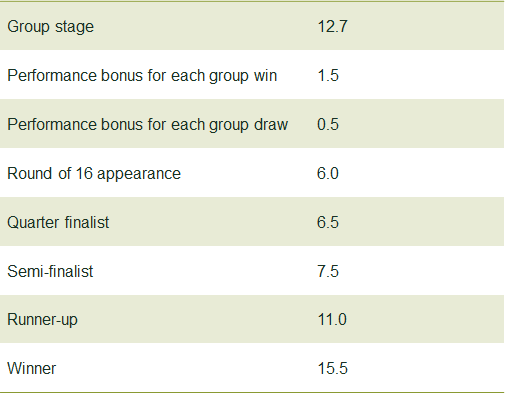

In particular, qualification for the Champions League has a major impact on a club’s revenues, as shown in the table below. In addition to the revenues shown, qualification for the Champions League would be expected to generate additional revenues from increased sales of tickets and merchandise, and TV rights and sponsorship for each club.

Table 1 Revenues directly associated with the Champions League (€m)

Source: UEFA (2016), ‘2016/17 Champions League revenue distribution’.

As an illustration of the impact of the Champions League, in 2010/11 and 2011/12 Juventus F.C. failed to qualify for the Champions League. In the same years, the club’s profit margins declined significantly, to -64% in 2010/11 and -26% in 2011/12.28 The club attributed the deterioration in its financial performance to the failure to qualify for the Champions League, as well as to a reduction in revenues from television and radio rights, among other factors.29

The importance of maximising the degree of competition

In order for any aid to be compatible with state aid rules, the aid must not lead to undue negative effects on competition. State aid frameworks, such as the Rescue and Restructuring Aid Guidelines, require measures to be introduced, such as divestments of business activities, to limit any distortions to competition.30

However, this requirement presumes that the preservation of a recipient harms its competitors. In contrast, in the case of any sports club, particularly football, the preservation of a competitor can enhance the popularity of the sport, maximising the brand and market value of all clubs. For example, intense rivalry between Real Madrid C.F. and F.C. Barcelona led to both clubs becoming more popular, with matches between them (‘El Clásico’) watched by more than 500m viewers, representing the largest audience worldwide for a domestic football match.31

Therefore, if a top football club were to exit the market, this may have an adverse impact on the club’s rivals and, more generally, on the league, by reducing competition, rather than enhancing competition, as fans are unlikely to easily switch allegiance between teams. The exit of a club may also affect the repayment of debt owed to other clubs, as a result of transfer payments.

Looking forward to next season?

So what lies ahead? In light of the in-depth state aid investigations that have recently taken place, it is possible that there may be a greater number of state aid investigations into football clubs in the future. Given the high-profile nature of any investigation, it is important for football clubs and governments to ensure compliance with state aid rules.32

This article has highlighted that a number of specific characteristics of football clubs need to be considered when applying the standard state aid frameworks to assess both the existence of aid as well as the compatibility of aid measures. In particular, it is important to take into account the business model of football clubs, the potential significant difference between the market and book value of the club’s players, as well as the importance placed by investors on non-financial factors, such as clubs’ on-field performance, league ranking and brand value.33

Whether the number of football-related state aid cases will continue to increase is yet to be seen. Given that many football fans have a strong attachment to their clubs, the investigations may be unpopular for the fans of those clubs involved. After all, some people think football is a matter of life and death. For others, it’s much more serious than that.

1 For further details, see European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Commission decides Spanish professional football clubs have to pay back incompatible aid’, press release, 4 July; and European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Commission clears support measures for certain football clubs in the Netherlands’, 4 July.

2 For further details, see Oxera (2014), ‘The charity league: state aid investigations in European club football’, Agenda, October.

3 The judgment is available at: http://www.bailii.org/ew/cases/EWHC/Admin/2014/2089.html.

4 European Commission (2013), ‘State aid SA.36105 (2013/N)—Germany, Fußallstadion Chemnitz’, C(2013) 5839 final, 2 October; European Commission (2013), ‘State aid SA. 3513 (2012/N)—Germany, Multifunktionsarena der Stadt Erfurt’, C(2013) 1517, 20 March; European Commission (2013), ‘State aid SA.35440 (2012/N)–Germany, Multifunktionsarena der Stadt Jena, C(2013) 1521, 20 March; European Commission (2013), ‘State aid SA.37109 (2013/N)–Belgium, Football stadiums in Flanders’, C(2013) 7889 final, 20 November; and European Commission (2013), ‘Aide D’Etat SA. 35501 (2013/N)—France, Financement de la construction et de la rénovation des stades pour l’EURO 2016’, C(2013) 9103 final, 18 December; and European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.37342 (2013/NN) – United Kingdom, Regional Stadia Development in Northern Ireland’, C(2014) 2235 final, 9 April.

5 This article is based on Oxera’s recent insights following Oxera’s work for a number of football clubs and member states throughout Europe—in particular, in the Netherlands, Spain and the UK, on state aid matters.

6 For state aid to exist, all four criteria must be met.

7 European Commission (2012), ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, EU State aid modernisation’, COM(2012) 209 final, 8 May.

8 UEFA (2015), ‘The European Club Footballing Landscape: Club Licensing Benchmarking Report’, p. 121.

9 Ascari, G. and Gagnepain, P. (2006), ‘Spanish Football’, Università Degli Studi di Pavia and Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, Journal of Sports Economics, 1 February.

10 ABC (2013), ‘Cañizares, ‘Artur Mas confía en que el Barça sea embajador de su proyecto soberanista’, 6 June.

11 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the State aid SA.29769 (2013/C) (ex 2013/NN) implemented by Spain for certain football clubs’, C(2016) 4046 final, 4 July. The Commission’s Decision has been appealed to the General Court. See Case T-865/16, Fútbol Club Barcelona v Commission, 7 December 2016; Case T-679/16, Athletic Club v Commission, 26 September 2016; Case T-854/16, QG v Commission, 30 November 2016; and Case T-846/16, QF v Commission, 30 November 2016.

12 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the State aid SA.33754 (2013/C) (ex 2013/NN) implemented by Spain for Real Madrid CF’, C(2016) 4080 final, 4 July. Real Madrid C.F. has appealed the Commission’s Decision to the General Court. See Case T-791/16, Real Madrid Club de Fútbol v Commission, 14 November 2016.

13 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the State aid SA.36387 (2013/C) (ex 2013/NN) (ex 2013/CP) implemented by Spain for Valencia Club de Fútbol Sociedad Anónima Deportiva, Hércules Club de Fútbol Sociedad Anónima Deportiva and Elche Club de Fútbol Sociedad Anónima Deportiva’, C(2016) 4060 final, 4 July. The Commission’s Decision was appealed to the General Court. See Case T-732/16, Valencia Club de Fútbol v Commission, 20 October 2016; Case T-766/16, Hércules Club de Fútbol v Commission, 7 November 2006; and Case T-901/16, Elche Club de Fútbol v Commission.

14 European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Commission clears support measures for certain football clubs in the Netherlands’, press release, 4 July.

15 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the state aid SA.41617—2015/C (ex SA.33584 (2013/C) (ex 2011/NN)) implemented by the Netherlands in favour of the professional football club NEC in Nijmegen’, C(2016) 4048 final, 4 July.

16 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the state aid SA.41612—2015/C (ex SA.33584 (2013/C) (ex 2011/NN)) implemented by the Netherlands in favour of the professional football club MVV in Maastricht’, C(2016) 4053 final, 4 July.

17 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the state aid SA.40168—2015/C (ex SA.33584—2013/C (ex 2011/NN)) implemented by the Netherlands in favour of the professional football club Willem II in Tilburg’, C(2016) 4061 final, 4 July.

18 European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 4.7.2016 on the measures SA.41614—2015/C (ex SA.33584—2013/C (ex 2011/NN)) implemented by the Netherlands in favour of the professional football club F.C. Den Bosch in ‘s-Hertogenbosch’, C(2016) 4089 final, 4 July.

19 See, for example, Garcia-del-Barrio, P. and Szymanski S. (2009), ‘Goal! Profit Maximization Versus Win Maximization in Soccer’, Review of Industrial Organization, 34:1, 17 February, pp. 45–68.

20 White, J. (2016), ‘Paris Saint-Germain take heed: Manchester City proof that money can’t buy success’, Eurosport, 6 April.

21 Blitz, R. (2014), ‘Manchester City hit with €60m UEFA financial fair play fine’, Financial Times, 16 May; Bounds, A. (2016), ‘Manchester City FC doubles profit to £20m’, Financial Times, 18 October; and White, J. (2016), ‘Paris Saint-Germain take heed: Manchester City proof that money can’t buy success’, Eurosport, 6 April.

22 See Scelles, N., Helleu, B., Durand, C. and Bonnal, L. (2014), ‘Professional Sports Firm Values Bringing New Determinants to the Foreground? A Study of European Soccer, 2005-2013’, Journal of Sports Economics, 17 June.

23 Oxera analysis, based on data from Dealogic and ORBIS. The book value of equity is reported as per the most recent financial accounts for the club prior to the transaction. To ensure consistency, the transaction price reflects the implied price for a 100% equity stake in the club.

24 Ahmed, M. and Burn-Murdoch, J. (2017), ‘Football’s smartest spenders in the multibillion-euro transfer market: Atlético Madrid scores highly but some historic superclubs suffer in comparison’, Financial Times, 3 February.

25 The book value is defined as purchase cost less annual amortisation. For the club’s book value, see F.C. Barcelona (2016), ‘Report 2015/2016’, p. 194, accessed 10 February 2017. For an estimate of the club’s market value, see Transfer markt website, ‘100 most valuable teams in the world’, accessed 10 February 2017.

26 See Transfer markt website, ‘Lionel Messi profile’, accessed 10 February 2017.

27 Juventus F.C. (2011), ‘Financial report at 30 June 2011’, p. 10.

28 Oxera analysis, based on data from Bloomberg. Profit margins are defined as earnings before tax (EBT) relative to revenues. The EBT margin takes into account earnings from player transfers. To some extent, it would be expected that higher revenues as a result of qualification for the Champions League would be partly offset by higher wage costs and transfer fees for the top players.

29 Juventus F. C. (2011), ‘Financial report at 30 June 2011’, p. 42.

30 European Commission (2014), ‘Communication from the Commission, Guidelines on State aid for rescuing and restructuring non-financial undertakings in difficulty’, Official Journal of the European Union, C249/1, 31 July, section 3.6.2.

31 For further details, see ‘El Clásico, The Story of the Rivalry between FC Barcelona and Real Madrid’, accessed 19 January 2017.

32 Van Maren, O. (2016), ‘EU State Aid Law and Professional Football: A Threat or a Blessing?’, European State Aid Law Quarterly Journal, 1, pp. 31–46.

33 See, for example, Scelles, N., Helleu, B., Durand, C. and Bonnal, L. (2014), ‘Professional Sports Firm Values Bringing New Determinants to the Foreground? A Study of European Soccer, 2005-2013’, Journal of Sports Economics, 17 June.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More