It’s what you know about who you know: market power in digital platforms

In digital markets, different types of platform operator compete vigorously for the attention of consumers. However, there are increasing concerns about their degree of market power, which can be difficult to assess using the traditional tools of competition and regulation. As calls for further regulation increase, authorities must ensure that any interventions do not lead to unintended consequences, such as reducing the gains that such platforms bring to society.

Over recent years, there have been increasing concerns around the degree of market power held by ‘big technology’ companies—particularly those that control important digital platforms. This has culminated in a series of high-profile antitrust investigations, merger reviews and detailed market investigations by competition authorities in Europe and around the world. Many policymakers are now calling for increased regulation of digital platforms to ensure that these markets work well for consumers. However, given the many examples of rapid innovation, frequent new entry, and freely provided services that exist online, could it be the case that consumers are already getting a good deal?

This article explores the basis for some of the common concerns of policymakers, by asking:

- how should we think about defining markets for digital services?

- what is different about market power in digital markets?

- what is the impact of digital services on consumers?

- what options do authorities already have to address any issues that arise?

The box below clarifies what is meant by digital platforms.

What do we mean by digital platforms?

Although there is wide diversity in the types of platforms and services on offer—as well as in how their business models operate—the common feature of all digital platforms is the bringing together of different groups of users in what economists describe as a ‘multi-sided market’.

There are now a wide array of platforms providing a range of services, including general search, user recommendations, holiday bookings, ride-hailing, video streaming, photo sharing, and many, many more. Depending on a platform’s business model, this can mean matching just two users (such as buyers with sellers on an e-commerce platform or in a ride-hailing app); or matching multiple users (such as producers, viewers and advertisers on a video sharing platform).

In any case, the platform’s success depends on stimulating a virtuous circle (positive externalities) of users on all sides who choose to use the same platform. To do this, many platforms adopt innovative business models, such as providing some or all of their services for free to certain group(s) of users to ensure their participation.

How should we define digital markets?

It can be hard to assess whether a group of similar digital services, such as WhatsApp, Twitter, Instagram and Snapchat, should be considered as constituting one market (e.g. messaging), two markets (e.g. text messaging and picture messaging), or multiple markets (e.g. text messaging, picture messaging, video messaging, etc.). This is even before we ask how other social media services (such as Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube and SoundCloud) feature as possible communications substitutes.

A common theme running through all these services is the control of consumer attention. More importantly, with attention comes consumer data, which is gathered and monetised in a variety of ways by digital platform operators. Therefore, although many digital platforms charge no tangible price for their service, consumers are effectively paying with their data at the personal cost of decreased privacy. Indeed, the global technology players—such as Microsoft, Facebook, Google, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, Spotify, eBay, Tencent and Alibaba—compete vigorously with each other, converging into similar markets as they attempt to uphold their share of consumer attention.

For example, Google moved from online search into the video streaming market with YouTube; Facebook spun off Facebook Messenger from its main social media platform to enter the messaging market, before later acquiring WhatsApp and Instagram and launching a video streaming platform, Facebook Watch; Apple entered the music streaming market with its acquisition of audio brand, Beats, before launching Apple Music; and Amazon has grown from being an online bookseller to a provider of online photo storage, music streaming and video streaming, as well as one of the world’s leading cloud computing providers.

In theory, at least, the question of robust market definition could be addressed with a modified version of the traditional SSNIP (small but significant non-transitory increase in price) test, by replacing ‘increase in price’ with some measure of ‘decrease in privacy’. However, in practice, both the data required and the behavioural biases exhibited by consumers when making the trade-off ‘in the moment’ (such as unduly disregarding their future privacy concerns) are likely to mean that this approach is difficult to apply.

What makes digital market power different?

Consumer trends evolve quickly in digital markets as technology advances. When combined with strong network effects, this can result in dramatic swings in market shares. For example, once-popular search engines such as Yahoo! and AltaVista have been eclipsed by Google; the ubiquity of Facebook is fading among younger people; and services such as Telegram are now competing on their enhanced privacy and security features.

This suggests that, while there may be considerable competition for the market, high market shares within the market could be the norm for the winners—until, that is, they are unseated by further innovation down the line. Similarly, many digital business models are characterised by large upfront investments in the technology required to create a new platform, followed by an easily scaled, high-margin operating model. When it comes to assessing market power, this means that traditional indicators—such as market shares and operating margins—may provide only part of the picture. Instead, we must consider the underlying sources of market power for digital platforms.

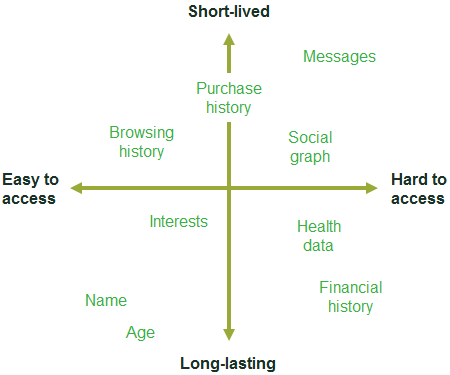

Advances in computing power and machine learning techniques have allowed firms to develop sophisticated algorithms and make much greater use of the enormous quantities of data they collect about their users. The concentration of many different (but related) datasets could therefore be a source of market power. However, not all data is created equal. Long-lasting general data is of low value and easy to replicate, while short-lived, precise details of consumer intentions at a specific point in time (such as a search for ‘nearby restaurant’ on a mobile device) are highly valuable and almost impossible to reproduce—see Figure 1.

In this context, enforcers might be tempted to rely on ‘direct effects’ assessments—drawing a conclusion of market power from evidence of an abuse (rather than vice versa). When doing this, it is important to be clear about what constitutes an abuse. Simply having a competitive advantage (such as a well-trained algorithm) and competing on the merits to gain market share is not necessarily the same as having and abusing market power or imposing restrictions to gain market share (such as tying, or exclusive dealing), which implies a freedom to act without regard to competitors.

To the contrary, the actions of many digital platforms appear to be highly motivated by the threat of actual and potential competition—such as the continual drive of competitors to innovate and remain relevant. The result has been a steady stream of new products and features for consumers as these firms seek to fend off the competition and enter new areas of business. It is therefore important to have a close look at the level of innovation directly as part of the overall competitive assessment.

Figure 1 Characteristics of different types of user data

What does this mean for consumers?

When thinking about the potential for specific competition concerns in digital markets, it is important not to lose sight of the bigger picture and the overall impact that these markets have. The influence of digital platforms has grown enormously over the last decade—so much so that they now reach into many aspects of our everyday lives.

This digital transformation has brought a host of substantial benefits to both consumers and businesses, particularly in terms of increased convenience and awareness of the options available when making purchases. It is estimated that European consumers save between 8 and 15 minutes per month due to the convenience of comparison websites; while the increased choice and awareness that these sites offer is thought to save them between €12 and €117 per year.1 Europe’s businesses benefit from digital platforms too, reporting easier access to wider markets and important insights from increased consumer feedback.2

This highlights the important—and delicate—trade-off that authorities must make when considering interventions in digital platform markets. While it is important to ensure that these markets continue to function well and operate fairly, it is also important to recognise and protect the substantial benefits that they offer. In particular, authorities should be cautious to avoid inappropriate interventions that may have unintended consequences, putting these benefits at risk.

For example, while the consolidation of data may be a source of market power, it is this same consolidation that is likely to provide the greatest opportunities for social gain by better matching users and revealing fresh insights into their preferences. This raises the critical question of whether an intervention to reduce this informational advantage will generate more social value through increased competition than it destroys by reducing the efficiency of the existing firms.

It also raises the question of how to properly weigh the pros and cons of digital market outcomes, particularly when it comes to certain short-run gains versus potential long-run harms. For example, in the short run, strong network effects mean that there are undoubted benefits in allowing a single, efficient platform to serve the whole market, while in the long run this has the potential to result in a reduced choice of service providers for consumers and businesses.

While the answers to these questions remain uncertain—both theoretically and empirically—what is certain is that a proper understanding of these competitive dynamics is crucial if we are to maximise the social gains from digital platforms while minimising the risk and impact of consolidating market power.

What options do authorities have if issues arise?

In light of the specific challenges and opportunities that digital markets can present, there are increasing calls from policymakers to impose stronger ex ante regulation on digital platforms. But is it really the case that authorities need further tools, or do they already have the tools they need to address the issues? And if new regulation is introduced, what should it consider?

First, it is important to recognise that digital platforms already face a raft of applicable regulation. A typical multifaceted firm—such as a social network operator—is governed by an array of laws, codes and directives at both the national and European level, having both positive and negative effects. For example:

- geo-blocking regulations prevent the unjustified discrimination of service offerings between member states, but can lead to increased prices for users with the lowest incomes;3

- the recently adopted reforms to the Audio Visual Media Services Directive (AVMSD) ensure that many media rules now extend to platforms, but increase compliance costs, which can have a negative effect on competition;4

- the proposed copyright reforms passed by the European Parliament (but still in discussion with the Council and Commission) give new rights to journalists and other content creators, while imposing stringent responsibilities on platforms to ensure that copyrights are respected and rights holders remunerated.5

On top of this, the standard antitrust provisions laid out in Articles 101 and 102 TFEU also apply. These, combined with traditional market analysis, appear to remain a suitable enforcement tool for many (if not most) of the competition theories of harm being raised. The underlying principles of identifying relevant markets and specific harms resulting from market power are still relevant—although the approaches taken to these traditional analyses may need some updating or adapting to reflect the specifics of modern digital markets.

Importantly, authorities should avoid ‘overreaching’ with competition law and drawing a distinction between market power concerns and consumer protection concerns—such as concerns about privacy—which these tools are not designed to support.

Finally, if further tools are deemed necessary, it must be recognised that there is no ‘one size fits all’ regulatory solution. Different technologies, datasets and business models all present unique risks and opportunities for society, implying different regulatory needs and priorities. Furthermore, while digital platforms often appear to be international, many of their products, services and associated regulatory issues are strongly localised. As such, a careful, case-by-case assessment is needed before sweeping regulations are imposed across the market.

Take, for example, the question of platform neutrality, which would prevent operators offering ‘paid prominence’ to their business users. While such paid prominence can result in reduced consumer welfare, this is not always the case. Depending on the mode of competition, the reverse can also be true. If competition is on quality, paid prominence offers the chance for higher-quality, higher-priced offerings to rise in the rankings, exposing consumers to the best options. However, if competition is purely on price, paid prominence can push the lowest-price offers down the rankings, reducing consumer surplus. Similarly, different platforms play very different roles in terms of their importance to businesses and their power as gatekeepers to consumers—and this can change over time. For example, as ad-blockers become more prevalent, paid ‘whitelisting’ (to allow adverts past the blocker) could become critical for businesses seeking to market themselves online.

In any event, paid prominence can lead to more polarised, ‘winner takes all’ markets. This can lead to a virtuous circle of success, prominence payments, and more success—as well as a corresponding vicious circle for ‘losers’. This, again, emphasises the need to weigh long-run dynamic impacts against short-run efficiencies in these markets, which suggests that a blanket ban on paid prominence is unlikely to be appropriate.

Conclusion

While traditional tools of competition and regulation remain relevant to digital platforms, the specific characteristics of market power can make their application more complicated. In many cases, the issue that authorities face is not so much one of controlling market power, but rather of ensuring that the market continues to work effectively for consumers now and in the long run.

Given the diverse range of digital platforms in Europe, particular care is needed to avoid unintended consequences arising from seemingly beneficial interventions—particularly those that could quash innovation and harm social outcomes in the long run, or those that inadvertently restrict platforms’ ability to deliver the best outcomes for consumers.

If calls for further regulation are successful, any proposed intervention should be shown to unambiguously improve social outcomes, which would require policymakers to build a thorough, evidence-based understanding of the complex dynamics on a market-by-market basis. Sweeping regulations that assume that all digital platforms are alike are likely to be inappropriate and risk limiting many of the benefits that digital platforms offer.

1 Oxera (2015), ‘Benefits of online platforms’, prepared for Google, October, p. 32.

2 Ibid., p. 38.

3 Regulation (EU) 2018/302 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 February 2018 on addressing unjustified geo-blocking and other forms of discrimination based on customers’ nationality, place of residence or place of establishment within the internal market and amending Regulations (EC) No 2006/2004 and (EU) 2017/2394 and Directive 2009/22/EC.

4 Directive (EU) 2018/1808 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 14 November 2018 amending Directive 2010/13/EU on the coordination of certain provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action in Member States concerning the provision of audiovisual media services (Audiovisual Media Services Directive) in view of changing market realities.

5 European Parliament (2018), ‘Parliament adopts its position on digital copyright rules’, press release, 12 September.

Download

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More