What problems can the European Commission’s New Competition Tool fix?

On 2 June, the European Commission launched consultations on proposals for a New Competition Tool (NCT) and its Digital Services Act package. As an NCT based on a market structure threshold (options 3 and 4 in the Commission’s proposals) would be similar to the UK’s market investigation regime in a number of ways, we discuss the lessons that can be learned from the UK’s market investigation experience as the Commission continues to consider and consult.

The Commission is proposing that the NCT will help to address gaps identified in the current EU competition toolkit to allow for timely and effective intervention.1 While the scope of the NCT is under consideration, the general objective is to ‘ensure fair and undistorted competition in the internal market’ and to address ‘structural competition problems that prevent markets from functioning properly and tilt the level playing field in favour of only a few market players’.2

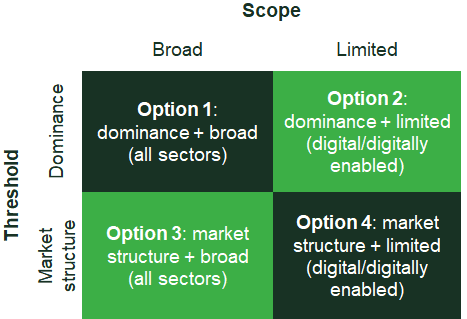

The Commission is presenting four options for the potential NCT that vary according to the threshold for opening an investigation; and the scope of the investigation.

As shown in Figure 1 below, the threshold for opening an investigation could be dominance-based (options 1 and 2) or market structure-based (options 3 and 4). A dominance-based option would address competition concerns arising from unilateral conduct by dominant companies, whereas a market structure-based option would not be limited to dominant firms and would allow the Commission to intervene when a structural risk for, or lack of, competition prevents the internal market from functioning properly.

The scope of the investigation could be broad/horizontal (options 1 and 3), or limited (options 2 and 4). A tool with broad/horizontal scope could be used across all sectors of the economy, whereas one with limited scope would focus more on digital or digitally enabled sectors.

Figure 1 The four options under the proposal for an NCT

The potential enforcement gap

The Commission’s initiative for the NCT reflects its concerns about potential enforcement gaps in its existing competition toolkit. These gaps relate to the ability to address all competition problems, and to do so in a timely manner. The Commission’s motivation for the NCT reflects both the potential for structural risks to competition, and the potential for weak or limited competition to continue unaddressed, as these issues cannot easily be resolved through Article 101 or 102 TFEU. Article 101 addresses anticompetitive agreements and concerted practices between companies, and Article 102 addresses the abuse by a company of its dominant position.

Structural risks to competition persist because there are limits to the extent to which Articles 101 and 102 can address harm that is expected to occur in the future. In many situations, these limits are placed in a reasonable way. However, particularly in the case of the fast-moving digital sector, where first-mover advantages can be hard to unwind and network effects mean that markets can be prone to ‘tipping’ (whereby one firm attracts most of the market), there may be a case for imposing remedies before irreversible harm is allowed to occur.3

Weak competition can persist despite Articles 101 and 102 due to structural market failures, consumer behavioural biases and/or tacit collusion, which are not the focus of the Article 101/102 framework. For instance, in its investigation into the retail banking market in 2016, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that consumer engagement and switching rates in personal current accounts were low, and that this was in part due to an underestimate of the gains from switching personal current accounts and a difficulty in accessing and assessing information on different current accounts.4

An NCT based on a market structure threshold (options 3 and 4 in the Commission’s proposals) would be similar to the UK’s market investigation regime in a number of ways. This article sets out the lessons that can be learned from the UK’s experience. First, we describe how the CMA market investigations regime works; then we consider the benefits of this tool above and beyond Articles 101 and 102; finally, we consider lessons that the Commission could learn from the UK experience.

The UK’s market investigation regime

In the UK, the 2002 Enterprise Act, and its amendments in the Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act 2013, provide the legal basis for the CMA’s market investigation regime powers.5

Market studies before market investigations

The process that leads to a CMA market investigation begins with a market study. These are commonly undertaken by the CMA, although sector regulators such as the Financial Conduct Authority (financial services) and Ofgem (energy) can undertake their own market studies.6

The market study stage allows the authority to conduct an initial assessment of how well the market is functioning and what the remedies could be before deciding whether to launch (and impose the associated costs of) a full market investigation. There are some similarities between a market study and the European Commission’s Sector Inquiries, where the Commission gathers information to better understand a particular market—although a market study can lead to a wider range of outcomes.7

The CMA can launch a market investigation when the findings of a market study give rise to reasonable grounds for suspecting that a feature (or combination of features) of a UK market or markets prevents, restricts or distorts competition.

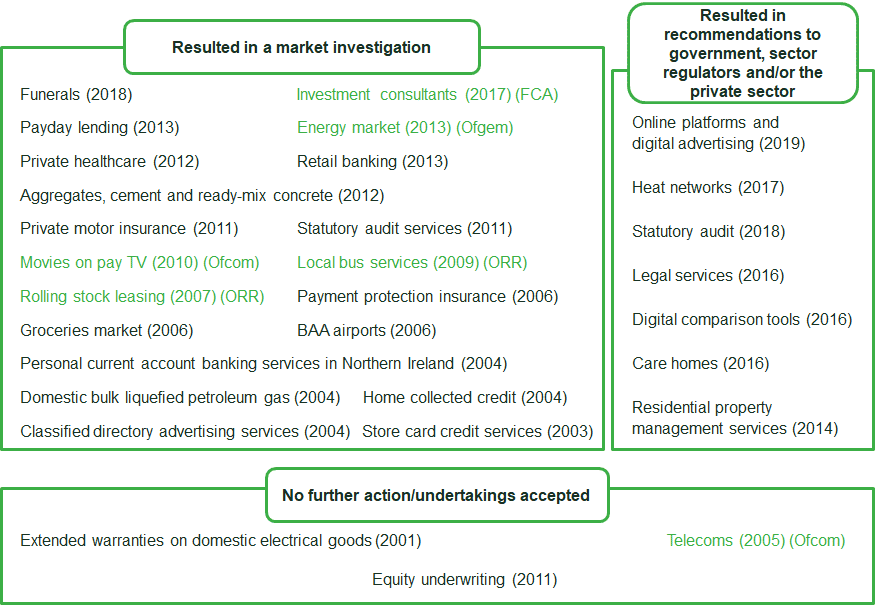

As set out in Figure 2, since 2001, 20 market investigations have been launched in the UK (15 based on CMA market studies, and five based on sector regulator market studies). In seven other market studies, at the end of the study the CMA preferred to make recommendations to government, sector regulators and/or the private sector rather than launch a full market investigation. There are a number of reasons why the Authority may wish to do this. For instance, in its Digital Advertising market study, the CMA decided to provide government with a suite of recommendations because the CMA (i) was confident that the government would carry out procompetitive reform in this area; and (ii) did not want to burden businesses given the current disruption to the economy.8

Figure 2 Market studies since 2001 and their outcomes

Source: Oxera analysis of CMA cases.

There is often an interaction and complementarity between the market investigation regime and the work of sectoral regulators in the UK. For instance, sectoral regulators can make market investigation references to the CMA, and the CMA, as a result of its market studies/investigations, can make recommendations to sector regulators. Furthermore, the UK market investigations regime can influence the development of UK and EU regulation, as the BT/Ofcom example in the box below illustrates.

BT functional separation of the wholesale division

A market investigation tool can shape the structure and development of regulation. A prominent example comes from the telecoms sector in which, in 2005, BT ‘voluntarily’ committed to functionally separate its wholesale division, to avoid going through the market investigation process.

Ofcom, the UK communications regulator, had conducted a strategic review of the sector and concluded that to achieve equal and non-discriminatory access to BT’s networks it was necessary to separate the retail and wholesale divisions of BT. However, at the time, the UK regulatory framework in telecoms did not give Ofcom powers to impose such a vertical separation remedy on BT directly. Ofcom could, however, make a market investigation reference to the CMA, which did have the necessary power to impose such a remedy if this were found to be appropriate following a market investigation.

To avoid going through the market investigation process, BT voluntarily committed to functionally separate its wholesale division (which later became Openreach), consistent with Ofcom’s intended policy intervention. This experience is likely to have contributed to the extension of regulatory powers in the 2009 revised Europe telecoms framework to include vertical structural separation as an additional ex ante remedy that is available to regulators.

Source: Ofcom (2005), ‘Final statements on the Strategic Review of Telecommunications, and undertakings in lieu of a reference under the Enterprise Act 2002’, 22 September.

Standard timetable and legal process

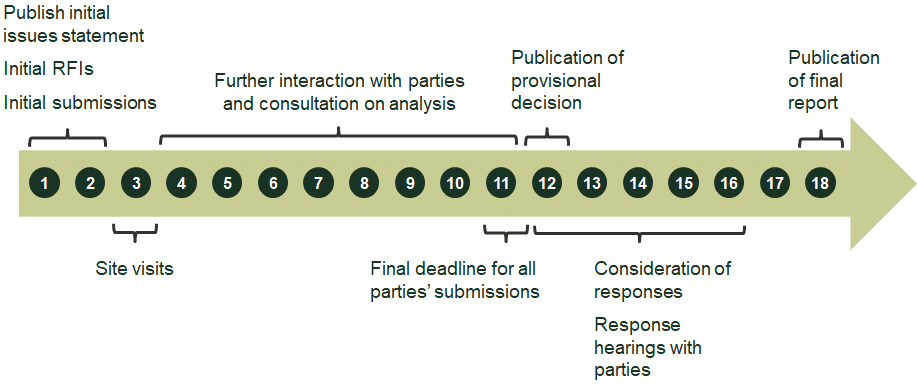

A market investigation involves a more detailed examination into whether there is an adverse effect on competition in the market(s) in question. The timeline for a typical market investigation is shown in Figure 3 below; however, the CMA can extend this period by up to six months (the Enterprise Act states that the CMA should publish its report within two years of the market investigation reference).9

Figure 3 Market investigation timeline (months)

Source: Competition and Markets Authority (2014), ‘Market Studies and Market Investigations: Supplemental guidance on the CMA’s approach’, January, p. 28.

If the CMA does find an adverse effect on competition, it can implement a wide range of legally enforceable remedies that are aimed at making the market more competitive in the future. When designing remedies, the CMA will assess the extent to which different remedy options are likely to be effective, and will determine whether to specify a finite duration (e.g. including a ‘sunset clause’).

Once the CMA has published its final report, parties can lodge an appeal with the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT) against the CMA’s decision. If a judgment of the CAT upholds an aspect of an appeal, this could lead to the investigation or a part of it being resubmitted to the CMA for reconsideration. In turn, appeals against CAT judgments can, if allowed, go forward to the Court of Appeal (in Scotland, the Court of Session) and, ultimately, to the Supreme Court. This provides an important system of checks and balances.

What are the costs and benefits of the market investigation tool?

The market investigation tool is not without costs. There is a direct cost to taxpayers (who fund the CMA) and firms (which engage with the CMA), but also an indirect cost in terms of diverting senior management away from the day-to-day running of their business.

However, the market investigation tool offers significant benefits. The CMA estimates that, between the financial years 2016 and 2019, the total direct consumer benefits from its interventions through the market study/investigation regime were £2.5bn, equating to c. £90 per UK household.10

First, the market investigation tool has allowed the CMA to implement market-wide structural and demand-side remedies that may not have been possible under Articles 101 and 102. For example, market investigations have led to divestments of airports, hospitals and cement businesses, as well as price control measures such as that for Yell (the publisher of the Yellow Pages).11 The CMA’s ex post assessment of the 2009 BAA market investigation remedies (which led to the divestment of Gatwick Airport in 2009, Edinburgh Airport in 2012 and Stansted Airport in 2013) quantified the benefits as amounting to c. £870m by 2020.12 These quantifiable benefits related to improved connectivity and choice, and downward pressure on fares, but the CMA’s report also points to a range of other improvements at the airports, such as improved service quality and efficiency, and increased investment in facilities.13 However, the CMA cannot impose fines in the context of a market investigation unless it makes a separate finding of an infringement of Article 101 or 102.14

Second, even where Article 101 or 102 may have allowed possible enforcement options, the market investigation tool might have allowed the CMA to introduce remedies more quickly. A market investigation must be concluded within 18–24 months (and a market study within 12 months), whereas antitrust investigations can last several years—for instance, the European Commission began its investigation into the Google Shopping abuse of dominance case in 2010 and published its final decision in 2017 (and Google is now in the process of appealing the decision).15

Third, market investigations also give the CMA a greater ability to engage with stakeholders throughout the process, by allowing submissions and hearings, as well as further interaction with parties and consultations on analysis (such as roundtables, confidentiality rings, disclosure rooms and working papers). In some cases, this, coupled with the absence of a risk of fines, can make the process less adversarial and more collaborative, with some parties’ views being aligned with those of the CMA. This is in contrast to Article 101/102 investigations, where firms tend to face a stark choice between settling, which can imply an admission of guilt with consequences for litigation risks, and fighting to defend their case.

What lessons can be learned?

A number of lessons can be learned from the UK market investigations regime.

Valuable flexibility to solve broader competition problems

The market investigation tool can help to resolve competition issues that Article 101/102 may not be able to address. These could include market-wide issues that do not fall within the Article 101 framework, or issues arising from unilateral market power that do not meet the Article 102 threshold.

Furthermore, given that market investigations tend to last 18 months and the legal framework imposes a two-year time limit, they can deliver remedies far more quickly than competition investigations, which tend to last many years.

Interaction with ex ante regulation

A market investigation tool can also help to shape the structure and development of regulation. As set out in the box above, in 2005, BT voluntarily committed to functionally separate its wholesale division, consistent with Ofcom’s intended policy intervention, to avoid going through the market investigation process. This experience is likely to have contributed to the extension of regulatory powers in the 2009 revised European telecoms framework to include vertical structural separation as an additional ex ante remedy that is available to regulators.

Certain issues are difficult to solve

Not all UK market investigations have had as much impact as was hoped.

Attempting to solve complex, structural issues in a market can be difficult and may require (i) an in-depth understanding of the industry; and (ii) coordination with various regulatory bodies and government organisations. While the market investigation regime is a flexible tool that allows the CMA to implement wide-ranging structural and behavioural remedies, even this may not be sufficient to solve all the market’s issues in one fell swoop. In these instances, the 18–24-month timeframe may act as a further constraint.

Generally, the UK’s experience has been that the remedies designed can still deliver some valuable improvements to consumers. However, a more systematic approach to the ex post assessment of market investigations could be valuable and could help to ensure that future investigations are opened only when the realistic expected net benefits are positive.

A less adversarial process provides for more effective solutions

In a market investigation, the features of the market are under investigation, rather than a specific firm or firms. In this environment, it may be possible to identify more effective solutions, and more quickly than would be possible with a more adversarial approach.

The route of appeal acts as an important check on the power of the authority

In the UK, following a market investigation, parties may lodge an appeal with the CAT against the decisions. The European Commission’s Inception Impact Assessment of the NCT currently makes no mention of judicial oversight. However, if the NCT were to be implemented, it would be important to have a route of appeal.

Riskiness of solving problems pre-emptively

The CMA market investigation tool is more concerned with addressing harms that are already happening because of structural market failures. However, the NCT also looks to address harm that is hypothesised to happen in the future because of the risk of future practices by dominant firms or existing structural market failures.

Attempting to solve these types of problem before they arise can be risky, especially in fast-moving markets, where it is difficult to know what the effects of these remedies would be and whether they would have any adverse consequences.

Overall, there are a number of lessons that the Commission can learn from the UK’s market investigation experience as it continues to consider and consult on its proposals for an NCT.

1 We set out our initial reactions to the European Commission’s recent consultations in a recent publication: Oxera (2020), ‘Platforms at the gate? Initial reactions to the Commission’s digital consultations’, June.

2 European Commission (2020), ‘Inception Impact Assessment: New Competition Tool (“NCT”)’.

3 For a longer discussion about the potential for digital markets to tip, see, for example, Oxera (2019), ‘Dealing with digital dominance: insights from Germany’, Agenda in focus, January.

4 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Retail banking market investigation: Final report’, 9 August.

5 Prior to the reorganisation of the UK Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and Competition Commission into the CMA, the market study would have been conducted by the OFT and the market investigation would have been conducted by the Competition Commission.

6 For instance, the CMA carried out its market investigation into investment consultancy and fiduciary management services following a reference from the Financial Conduct Authority in September 2017 at the conclusion of the latter’s Asset Management market study—see Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Investment Consultants Market Investigation: Final Report’, 12 December.

7 These outcomes could include: a clean bill of health; actions that improve the quality and accessibility of information to consumers; encouraging businesses in the market to self-regulate; making recommendations to the government to change regulations or public policy; or taking competition or consumer enforcement action. For more details on Sector Inquiries, see European Commission, ‘Antitrust: Sector inquiries’, accessed 10 July 2020.

8 Competition and Markets Authority (2020), ‘Online platforms and digital advertising: market study final report’, 1 July.

9 UK government, Enterprise Act 2002.

10 Competition and Markets Authority (2019), ‘CMA impact assessment 2018/19’, 18 July, para. 3.22. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates that there were 27.8m households in 2019—see Office for National Statistics (2019), ‘Families and households in the UK: 2019’, 15 November, accessed 14 July 2020.

11 Competition Commission (2009), ‘BAA airports market investigation: A report on the supply of airport services by BAA in the UK’, 19 March. Competition and Markets Authority (2014), ‘Private healthcare market investigation: Final report’, 2 April. Competition Commission (2014), ‘Aggregates, cement and ready-mix concrete market investigation’, 14 January. Competition Commission (2006), ‘Classified Directory Advertising Services market investigation’, 21 December.

12 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘BAA airports: Evaluation of the Competition Commission’s 2009 market investigation remedies’, 16 May.

13 This is in addition to the development of positive long-term relationships with airlines over issues such as airport charges, route development, and innovations to maximise limited runway capacity. Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘BAA airports: Evaluation of the Competition Commission’s 2009 market investigation remedies’, 16 May.

14 UK government, Enterprise Act 2002.

15 For further details, see European Commission, ‘Antitrust/Cartel Cases: 39740 Google Search (Shopping)’, accessed 1 July 2020.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More