Spotlight on tax and state aid: the General Court’s Apple judgment

In July 2020, the EU General Court annulled the European Commission’s decision that Ireland had granted illegal state aid of at least €13bn to Apple through two tax rulings. The General Court’s judgment in the Apple case was one of the most keenly awaited judgments in the area of state aid. What are the key economic issues raised by the General Court in this case? More generally, how can multinational companies and national tax authorities mitigate state aid risks?

In June 2014, the European Commission began three in-depth investigations to examine whether rulings granted by tax authorities in Ireland, the Netherlands and Luxembourg comply with state aid rules. The rulings in question set out how the level of corporate income tax to be paid by Apple, Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade in the respective countries would be calculated.1 The Commission concluded that the tax rulings agreed by the respective tax authorities with Apple, Starbucks and Fiat Finance and Trade all constituted illegal state aid, and required the three companies to repay the aid.2 In the case of Apple, the Commission ordered the company to repay aid amounting to €13bn plus interest, representing the largest-ever aid recovery demand.3

Following appeals of the Commission’s decisions, in September 2019, the General Court upheld the Commission’s decision that Fiat Finance and Trade had received illegal state aid, but annulled the Commission’s decision on Starbucks.4 This left many to theorise about the outcome of the Apple case.

On 15 July 2020, the General Court annulled the Commission’s decision in the Apple case. This was on the basis that the Commission had failed to prove that Apple’s tax arrangements had granted a selective advantage to Apple’s two Irish branches in question, and therefore had not shown that the tax arrangements constituted aid.5

The General Court’s judgment has major implications for the Commission’s state aid investigations into the tax arrangements of multinationals. This article discusses the key economic issues from the judgment in the Apple case. We then look at how multinationals can mitigate state aid risks in their arrangements with tax authorities.

The Apple case: which tax rulings were in question?

The Commission’s investigation focused on the Irish branches of two subsidiaries of the Apple Group incorporated in Ireland: Apple Sales International (ASI) and Apple Operations Europe (AOE).

- ASI’s Irish branch was responsible for procurement, sales and distribution activities associated with the sale of Apple’s products to related parties and third-party customers across Europe, the Middle East, Africa and the Asia–Pacific region.

- AOE’s Irish branch was involved in the manufacturing and assembly of computer products (the iMac and MacBook), all of which are manufactured for Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

While ASI and AOE were incorporated in Ireland, they were not considered to be tax-resident in Ireland. As a result, they were required to pay corporation tax in Ireland on the taxable profit of their Irish branches only (i.e. on any profits arising directly or indirectly from their Irish branches).

How was the taxable profit of ASI’s and AOE’s Irish branches determined?

In 1991, Irish Revenue issued a tax ruling for ASI and AOE that set out the method through which ASI and AOE should allocate profits to their Irish branches to determine the branches’ annual corporation tax in Ireland. In 2007, a new tax ruling replaced the 1991 ruling (see the box below).

Overview of ASI’s and AOE’s tax rulings

ASI’s and AOE’s tax rulings were based on the transactional net margin method (TNMM), which applies a profit indicator to the branch’s cost base to determine the level of taxable profit.

ASI

- According to the 1991 tax ruling, the taxable profit of ASI’s Irish branch should be calculated as 12.5% of all branch operating costs, excluding materials for resale.

- According to the 2007 tax ruling, the taxable profit of ASI’s Irish branch should be calculated as 10–15% of branch operating costs, net of charges from Apple affiliates and materials costs.

AOE

- According to the 1991 tax ruling, the taxable profit of AOE’s Irish branch should be calculated as 65% of the branch’s operating expenses up to an annual amount of $60m–$70m, plus 20% of any of the branch’s operating expenses in excess of this threshold.*

- According to the 2007 tax ruling, the taxable profit of AOE’s Irish branch should be calculated as the sum of 10–15% of the branch’s operating costs and 1–5% of the branch’s turnover as a return on Apple’s IP, less the branch’s capital allowance for plant and buildings.*

Note: * Operating expenses exclude the charge from Apple-affiliated companies for research and development.

Source: European Commission (2016), ‘Commission Decision of 30.8.2016 on state aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) implemented by Ireland to Apple’, 30 August, section 2.2.

What errors were identified by the General Court in the Commission’s assessment?

The Commission argued that Ireland had granted Apple a selective economic advantage, primarily on the basis that the calculation of ASI’s and AOE’s taxable profits in Ireland excluded their profits derived from the IP licences for the procurement, manufacture, sale and distribution of Apple Group’s products.6 However, as outlined below, a number of errors were identified by the General Court.

The Commission’s assessment of the allocation of IP rights and the determination of taxable profits

The Commission concluded that the Irish tax authorities had incorrectly allocated ASI’s and AOE’s profits from their IP licences to their head offices, which had no physical presence or employees. As such, the Commission concluded that ASI’s and AOE’s head offices could not control and manage the IP licences or take on the risks associated with the licences. Furthermore, as ASI and AOE did not have any taxable presence in any other tax jurisdiction besides Ireland,7 the Commission concluded that ASI and AOE were ‘stateless’ in relation to their profits from the IP licences over the period when the tax rulings were in force.8

The Commission considered that the IP licences held by ASI and AOE had contributed significantly to the income of their two branches in Ireland, and that the Irish branches were the only entities that could have been allocated the profits from the IP licences.9 Therefore, the Commission concluded that the profits from the IP should have been allocated to the Irish branches, and taxed in Ireland, and that the failure to do so led to ASI’s and AOE’s taxable profit in Ireland being significantly underestimated.

In addition, the Commission put forward arguments that, even if it had been correct to allocate the IP licences to ASI’s and AOE’s head offices, the profit allocation method was incorrect. According to the Commission, this led to the underestimation of ASI’s and AOE’s taxable profit in Ireland due to methodological issues.10

What errors in the Commission’s assessment were identified by the General Court?

According to the General Court, the Commission made three errors in its assessment of the allocation of IP rights, which related to the allocation of profits under the normal tax regime in Ireland, the application of the arm’s-length principle, and the interpretation of the OECD’s guidelines.

First, the General Court considered that the Commission’s presumption that ASI’s and AOE’s head offices had no physical presence and employees was not sufficient to conclude that the profits from the IP licences should have been allocated to the Irish branches for corporate tax purposes.11 The General Court noted that the Commission’s methodology is based on an ‘exclusion approach’, which assumes that the profits from the IP rights should automatically be allocated to the branches if the IP rights cannot be allocated to the head offices. The General Court considered that profits should be allocated to the economic entity that controls the assets in question, and that a lack of physical presence is not sufficient to prove the lack of control.12

Second, the General Court considered that, instead of the exclusion approach adopted by the Commission, the arm’s-length principle should be applied based on an analysis of the functions performed by the head offices and the Irish branches, as well as the terms of the transactions between the head offices and the Irish branches. The General Court implied that the application of the arm’s-length principle required the transactions to be valued as if they had been carried out between unrelated parties, each acting in its own best interest.13

Finally, the General Court concluded that the choice of the entity to which the profits are allocated for corporate tax purposes (i.e. the permanent establishment) cannot be made without a detailed analysis of the functions performed by the economic entities involved, in line with the Authorised OECD Approach (AOA).14 The General Court went on to conclude that the Commission had failed to apply the AOA correctly.15

The General Court also identified a number of errors made by the Commission in relation to its argument that, even if it had been correct to allocate the IP licences to ASI’s and AOE’s head offices, the arm’s-length pricing method had been applied incorrectly.16

In particular, the Commission argued that the arm’s-length pricing method that had been used—the TNMM, which applies a profit indicator to one of the entities to the transaction—had been applied incorrectly to the Irish branches, given that, according to the Commission, they undertook complex activities. In principle, the Commission claimed that the TNMM should be applied to the entity for which the profit indicator can be more reliably estimated.17 However, the General Court concluded that the Commission had failed to prove that the functions performed by the Irish branches were too complex or unique for the TNMM to be applied accurately to them, and that the Commission had merely asserted that the approach had led to a decrease in ASI’s and AOE’s taxable profit.18

Similarly, the General Court concluded that the Commission had failed to prove that the choice of operating costs as the profit indicator was incorrect.19 More generally, the General Court concluded that the Commission had failed to show that ASI’s and AOE’s taxable profit fell outside the arm’s-length range.20

How should profits from IP be allocated for tax purposes?

As discussed above, the General Court concluded that the Commission had incorrectly applied the AOA to determine the allocation of profits between ASI’s and AOE’s Irish branches and their head offices.21

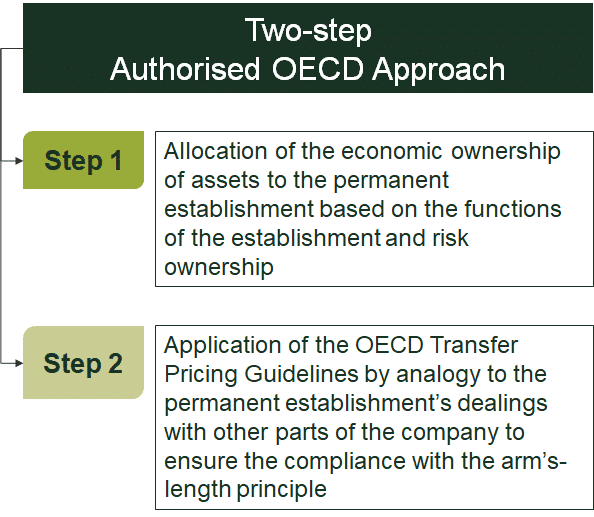

The rationale behind the AOA is to allocate profits to the permanent establishment that it would have earned if it was a ‘distinct and separate’ enterprise carrying out similar functions under similar conditions.22 As illustrated in Figure 1, as highlighted by the General Court, according to the OECD’s guidelines, in order to identify the permanent establishment, the first step is to allocate profits from transactions among the different entities of the multinational based on a detailed analysis of each entity’s assets, functions and risks.23 The AOA allocates the economic ownership of assets for which the main functions relevant to their economic ownership are performed in the permanent establishment.

Figure 1 The Authorised OECD Approach to profit attribution

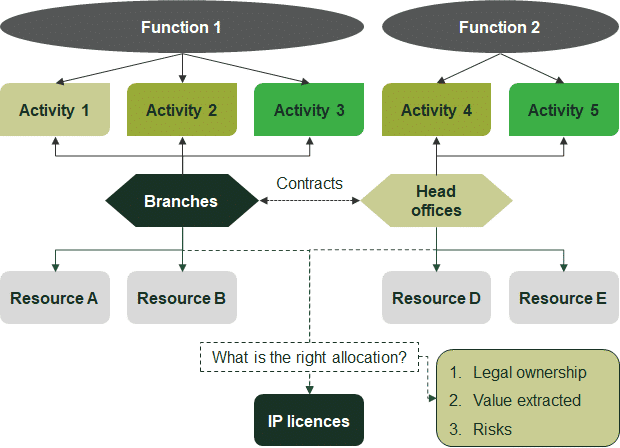

An illustrative example of ‘functional analysis’ involving intangible assets is provided in Figure 2 below. The first step in determining the allocation of profits from intangible assets, such as the IP, is to identify the structure of the activities that are performed by the various entities and the resources required. In addition, it is necessary to assess a number of other factors, such as the details of the legal ownership, the risks associated with the assets, and, most importantly, the value created as a result of owning the asset.24

Figure 2 Illustrative example of functional analysis

In the second step of the AOA, the arm’s-length price of transactions between different entities of the multinational company needs to be established based on the terms and conditions of transactions between unrelated independent parties, each acting in its own best interest.25

As highlighted in the Apple case, it is important to ensure that the OECD’s arm’s-length pricing methodology is selected and applied appropriately. This choice should be informed by the financial and economic characteristics of the functions performed by the permanent establishment. Furthermore, an appropriate profit indicator should be selected to reflect the specifics of the transaction in question, with the resulting estimate of the indicator being in line with evidence from comparable transactions between independent parties at the time of entering into the tax ruling.

More generally, economic and financial analysis can assist with the application of the AOA in cases where intangible assets play a significant role. Where one branch of a multinational company uses IP owned by another branch of the company, in order to estimate the appropriate transfer price that determines the resulting allocation of profits between the two branches a number of techniques can be used to value IP, as outlined in the box below.

Overview of methods to value IP

Market-based method. This method values the IP based on similar market transactions (or comparators). Licences agreed between the IP owner and ‘similarly situated’ licensees can be used to estimate the market-tested value of the IP rights, provided that the transactions are comparable (or can be reasonably adjusted to be comparable). However, given that IP rights reflect the unique characteristics of the intangible assets, identifying similar transactions can be challenging. In such situations, the scope of the benchmarking could be extended to include IP rights with comparable utility and technological specifications.1

Income-based method. This method estimates the value of IP based on the present value of future cash flows from a particular IP, which can be considered a proxy for the willingness-to-pay by downstream users of the IP.2 To implement this method, cash flow forecasts need to be derived, based on assumptions regarding the future profits to be generated by the entity as a result of the IP rights.

Cost-based method. This approach is based on the costs incurred to develop the IP (e.g. R&D, marketing) with an allowance for a reasonable return on these costs as well as a return on the risks borne by IP investors. Conceptually speaking, there are two main cost-based methodologies: historical cost and replacement cost.3 However, a disadvantage of this approach is that it does not account for the revenues and profits arising from the innovation, and therefore might not reflect the ‘true’ contribution of the innovation.

Source: 1 European Commission (2015), ‘Fact Sheet Intellectual Property Valuation’, June. 2 European Commission (2017), ‘EU joint transfer pricing forum report on the use of economic valuation techniques in transfer pricing’, 16 October. 3 European Commission (2013), ‘Final Report from the Expert Group on Intellectual Property Valuation’, 29 November.

Looking ahead

Once again, the General Court has upheld the Commission’s approach of applying state aid rules to tax rulings, and, in particular, has validated the role of the arm’s-length principle and the OECD’s guidelines. However, the General Court has set a high bar in terms of the level of evidence that must be provided by the Commission to demonstrate that the methodology in a tax ruling confers an economic advantage.

On the day of the General Court’s judgment, the Commission announced that it will continue to examine tax planning measures under state aid rules.26 In light of the judgment, it is possible that the Commission could undertake more detailed economic and financial analysis, as required under the OECD Guidelines, in future tax cases to assess whether tax rulings confer an economic advantage.

Therefore, in order to mitigate state aid risks, multinationals and tax authorities may consider it advisable to give due consideration to the allocation of profits across the different entities of the multinational. Economic and financial analysis can support the legal analysis in helping to determine the appropriate allocation of profits by assessing the functions, assets and risks of the different entities, particularly in those tax cases involving the allocation of profits from the IP, where a detailed assessment of the value of the IP may be required.

As highlighted in the Apple case, it will also be important to ensure that there is the necessary economic and financial evidence to justify the choice and the application of the arm’s-length pricing methodology when entering into tax rulings.

1 European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA. 38375 (2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) – Luxembourg alleged aid to FFT’, 11 June. European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38374 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) – Netherlands Alleged aid to Starbucks’, 11 June. European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) – Ireland Alleged aid to Apple’, 1 June.

2 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October. European Commission (2015), ‘Commission decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA.38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October. European Commission (2016), ‘Commission decision of 30.8.2016 on state aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) implemented by Ireland to Apple’, 30 August. For an overview of the tax state aid cases, see Robins, N. (2019), ‘Tax rulings: an overview of EU state aid cases’, foreword to Concurrences e-Competitions Special Issue on tax rulings, 1 August.

3 European Commission (2016), ‘State aid: Ireland gave illegal tax benefits to Apple worth up to €13 billion’, 30 August.

4 For further details, see Oxera (2019), ‘State aid spotlight on tax: the General Court’s judgments on Fiat and Starbucks’, Agenda in focus, October.

5 General Court (2020), ‘Judgment of the General Court (Seventh Chamber, Extended Composition) in cases T‑778/16 and T‑892/16’, 15 July. For a tax measure to constitute state aid, in addition to conferring a selective economic advantage on the company in question, it must be granted directly or indirectly through state resources and be imputable to the state, and it must have the potential to distort competition and trade between member states.

6 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 32.

7 According to the Commission, this was aside from AOE’s branch in Singapore. European Commission (2016), ‘Commission decision of 30.8.2016 on state aid SA.38373 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP) implemented by Ireland to Apple’, 30 August, para. 51.

8 Ibid., para. 52.

9 Ibid., para. 319.

10 Ibid., section 8.2.2.3.

11 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 186.

12 Ibid., para. 186.

13 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 228. OECD (2006), ‘Annual Report on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Conducting Business in Weak Governance Zones’, 8 June.

14 General Court (2020), op. cit., paras 242 and 284. OECD (2006), ‘Annual Report on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Conducting Business in Weak Governance Zones’, 8 June, paras 240 and 242.

15 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 244.

16 General Court (2020), op. cit., paras 351, 407 and 412.

17 OECD (2017), ‘OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations’, July, para. 2.69.

18 General Court (2020), op. cit., paras 331 and 340.

19 Ibid., paras 365 and 414.

20 Ibid., para. 476.

21 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 245.

22 In practice, however, there can be a number of practical challenges associated with applying the AOA. See Collier, R. and Vella, J. (2019), ‘Five Core Problems in the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments’, World Tax Journal, 11:2, 1 April.

23 General Court (2020), op. cit., para. 242. OECD (2010), ‘2010 Report On The Attribution Of Profits To Permanent Establishments’, 22 July. OECD (2018), ‘Additional Guidance on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments, BEPS Action 7’, March.

24 OECD (2017), ‘OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines’, July, pp. 264–265.

25 OECD (2010), ‘2010 Report on the Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments’, 22 July, para. 10.

26 European Commission (2020), ‘Statement by Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager following today’s Court judgment on the Apple tax State aid case in Ireland’, 15 July.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More