EU pharmaceutical strategy: innovative medicine?

The European Commission is setting out a road map of interlinked policies across various sectors, with the stated aims of: (i) improving outcomes for Europeans; (ii) increasing competition and the competitiveness of European businesses; and (iii) supporting European innovation. In this Agenda article, we look at the Commission’s recently announced Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe.1 The strategy focuses on improving access to innovative and affordable medicines, and supporting competitiveness and innovation in the pharmaceutical industry. These objectives are also linked to wider EU strategies, such as the Green Deal, digital policies, and broader innovation policy.

The Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe has four main objectives:2

- ensuringaccess to affordable medicines for patients, and addressing unmet medical needs;

- supporting competitiveness, innovation and sustainability of the EU’s pharmaceutical industry and the development of high-quality, safe, effective, and greener medicines;

- enhancing crisis preparedness and response mechanisms, and addressing security of supply;

- ensuring a strong EU voice in the world, by promoting a high level of quality, efficacy, and safety standards.

Driving innovation

The primary theme of the strategy is a focus on supporting innovation in the pharmaceutical industry, recognising the link between successful innovation and sustainable growth (set out in a second strategy document concerning innovation more broadly, released by the Commission on the same day).3 This also ties in with the EU’s broader aims of fostering an environment that allows European businesses to achieve global success.

The strategy’s focus on innovation could be seen as a response to an apparent relative decline of the European pharmaceutical industry over the last decade. Europe’s share of global pharmaceutical market revenue has decreased from just under 30% in 2010 to around 22% in 2019.4 Furthermore, while pharmaceutical R&D expenditure in Europe increased by 30.1% between 2010 and 2018, stronger growth of 52.9% in the USA was observed over the same period.5 A renewed focus on innovation could bolster the EU pharmaceutical industry going forward and reverse this decline.

The strategy emphasises that one of the key areas where innovation is required is in addressing unmet medical needs; these include the lack of treatments for neurodegenerative diseases, rare diseases, and paediatric cancers, and the lack of new antimicrobials to combat the growing problem of antimicrobial resistance. Current investment is lacking in these areas due to an absence of commercial incentives and/or limited scientific knowledge. For example, in the case of rare diseases, the low number of cases often deters a single pharmaceutical supplier from undertaking the costly investments necessary to develop a treatment for a particular disease as it cannot guarantee a sufficient commercial return.

Thus, according to the strategy, public authorities must implement policies that can address this market failure by altering the commercial incentives of pharmaceutical suppliers. To this end, a number of policies are proposed in the strategy to encourage and reward innovation in areas of unmet medical needs. Studies are already under way that will inform how to better tailor the system of incentives provided by the EU in order to stimulate innovation in these areas. Furthermore, the Commission proposes to facilitate collaboration between a range of stakeholders (including regulators, academia, healthcare professionals, and healthcare payers) to better align research priorities with the needs of patients.

The strategy further highlights the important role that digital health initiatives will play in the future, and suggests a number of policies to encourage innovation in this area. These include improving cross-border exchange and analysis of health data, and supporting collaborative projects that use AI and high-performance computing. Such initiatives align with the EU’s broader policy of encouraging digital transformation across Europe.6

Generic and biosimilar competition

While the strategy focuses on innovation, which is driven by originators of medicines, it also recognises the important role that generic and biosimilar medicines play in the later stages of the pharmaceutical life cycle. The competition provided by these medicines drives down prices, and is thus instrumental in achieving the Commission’s objective of ensuring patient access to affordable medicines.

Our recent study of the generic medicines market in the UK showed that, on average, the generic price in the six months after loss of exclusivity is 70% lower than the price of the originator’s branded product before the loss of exclusivity. This falls to 80–90% lower over a four-year period.7 Hence, there are very large benefits from encouraging effective competition in the market for generic medicines.

These benefits are more likely to materialise when generic competition is embedded within a well-designed market framework. Thus, the Commission’s proposal to increase cooperation between national pricing and reimbursement authorities and healthcare payers (for example, through joint procurement, and knowledge-sharing of which procurement systems achieve the best outcomes) could help to reap the benefits of generic competition.

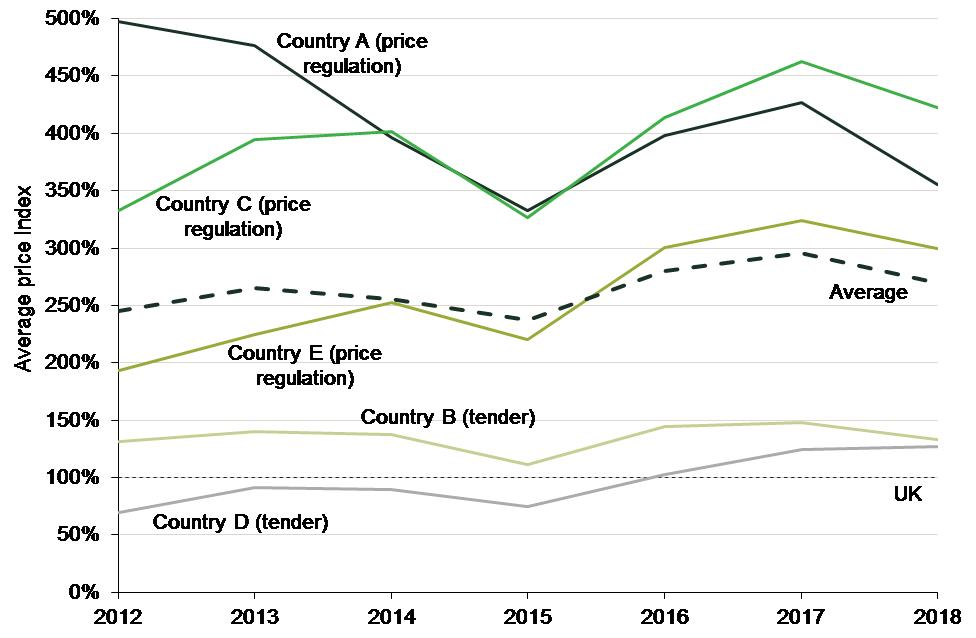

Our study showed that average prices of generic medicines vary widely among European countries, suggesting that some countries could benefit from learning from the experiences of others. Figure 1 below compares the average actual manufacturer selling prices across five EU countries and the UK.

Figure 1 Average generic price in selected EU countries relative to the UK, 2012–18

In our study, we noted that one of the main factors that is likely to be driving these price differentials is the regulatory system guiding the pricing of generic medicines in each country—with the systems that encourage competition between generic suppliers tending to produce the lowest generic prices.

- The UK price regulation system provides strong incentives to all key players to encourage the use of generic medicines. For example, the reimbursement structure incentivises pharmacies to dispense the least expensive of the generic products, which in turn incentivises generic suppliers to offer competitive prices to pharmacies.

- In Countries B and D, a tender system is used to establish the generic retail price, with the healthcare system reimbursing patients only at the lowest price among all available products. As in the UK, competition plays an important role in this system, which may explain why generic prices in these two countries tend to be lower.

- In Countries A, C and E, the reimbursement price for generic medicines is regulated, usually with reference to the originator’s price. This can lead to lower prices for branded versions of off-patent medicines, but provides weaker incentives for generic producers to compete. Accordingly, average generic prices in these countries tend to be higher than in the other countries.

We further noted that pricing and reimbursement approval for a generic medicine takes much longer in Countries A and C than in the UK and Country B, which is likely to reduce the number of generic entrants, and thus the intensity of generic competition, in the former. The Commission’s proposal to reduce regulatory approval times for medicines is welcome in this context.

Moreover, not only does generic competition facilitate access to affordable medicines—it can also support innovation. Lower prices mean that public health authorities spend less on medicines, which can facilitate higher expenditure on policies to encourage innovation (such as subsidies).

Balancing the trade-offs

Overall, the Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe sets out a clear path for strengthening the EU pharmaceutical industry, so that it continues to serve public health and contributes to a stronger European Health Union. This will be achieved through a focus both on market-driven innovation that meets patient needs, and continued support of generic and biosimilar competition in order to ensure access to affordable medicines. There can nonetheless be some tension between these two aims of fostering longer-term investment incentives and increased generic competition. The Commission is also signalling that it will continue to rely on competition enforcement to ensure that effective competition prevails once originators lose the patent protection designed to support those investment incentives.

1 European Commission (2020), ‘Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe’, Brussels, 25 November.

2 European Commission (2020), ‘Press release: Affordable, accessible and safe medicines for all: the Commission presents a Pharmaceutical Strategy for Europe’, Brussels, 25 November.

3 European Commission (2020), ‘Making the most of the EU’s innovative potential: An intellectual property action plan to support the EU’s recovery and resilience’, Brussels, 25 November.

4 Statista (2020), ‘Distribution of global pharmaceutical market revenue from 2010 to 2019, by region’.

5 Oxera calculations based on: EFPIA (2020), ‘The Pharmaceutical Industry in Figures’, p. 5.

6 For further details on the potential impact of this digital transformation see: Oxera (2020), ‘The impact of the Digital Services Act on business users’, study prepared for Allied for Startups, 23 October.

7 Oxera (2019), ‘The supply of generic medicines in the UK’, study prepared for the British Generic Manufacturers Association, 26 June.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More