Will the end of a golden age for UK transport infrastructure be a catalyst for a green era?

Arguably, the UK has gone through a golden age of transport infrastructure planning and delivery in recent years. Since the turn of the millennium, transport capital budgets have grown and grown, with the £96bn integrated rail plan for upgrades in the Midlands and the North, £27.4bn announced for the second Roads Investment Strategy, and £5.7bn set aside to transform local transport in eight city regions.

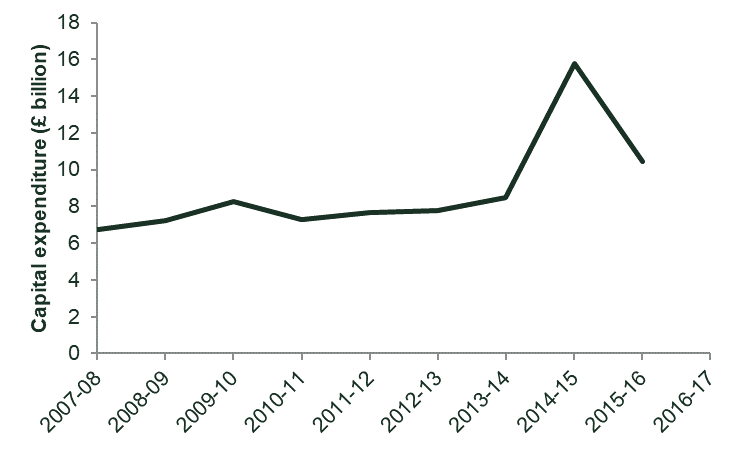

Department for Transport capital budgets have increased

As a result, successive Prime Ministers have made bold claims about the UK government’s record of ever-increasing capital investment in transport infrastructure.

In 2014, David Cameron remarked, ‘We are now not only spending as much on rail as any Government since Victorian times, but on roads we are spending more than any Government since the big expansion of the 1970s.’1

Six years later, Boris Johnson heralded a ‘massive programme of investment in local transport, starting with a record-breaking £5 billion of new investment in buses and bicycles’.2

Transport capital budgets survived the cuts of the Autumn Statement yesterday, but with fiscal consolidation there are questions about whether the budgets can grow further. Are the prospects now limited for enhancements in the coming years? And do existing projects face future pain? Does this therefore mark the end of this golden era for transport?

This article examines why pressures building before and after the pandemic make investment in conventional transport infrastructure appear less attractive in all but the most capacity-constrained parts of transport networks—but also offers some reasons to be hopeful. In particular, the golden age of transport infrastructure could transform into a new green era, empowering the sector to rise to the huge environmental challenges we face.

Pressures on transport

Inflation in the UK has risen to a 40-year high.3 However, construction materials inflation has been substantially higher than the current headline rate of CPI (16.7% compared to 11.1%, and down from a recent high of 26.8%), with substantial individual price rises for some construction materials (such as 60% for gravel and 27% for concrete products).4

These price rises are compounded by labour shortages and longer lead-in times for the delivery of materials and plant machinery. A combination of geopolitical events such as Brexit, the war in Ukraine, and COVID-19 lockdowns in China are all contributing to the general and relative price rises.

These may or may not be temporary rather than sustained pressures. However, with the UK government protecting but not raising capital budgets to absorb these substantial pressures, the budgets of infrastructure-focused departments in Whitehall are facing a real-terms cut.

In practical terms, this means the Department for Transport (DfT) and its delivery bodies need to find substantial efficiencies—or more likely are faced with the prospect of less maintenance, renewals and enhancement activity in the coming years. This pressure has only worsened—and with the outlook uncertain, could worsen still.

Perhaps the inevitable combination of these impacts will be delays to projects, with space in future investment periods taken up by an increasing proportion of legacy projects, and larger budgets for renewals and maintenance to offset real-terms cuts this period.

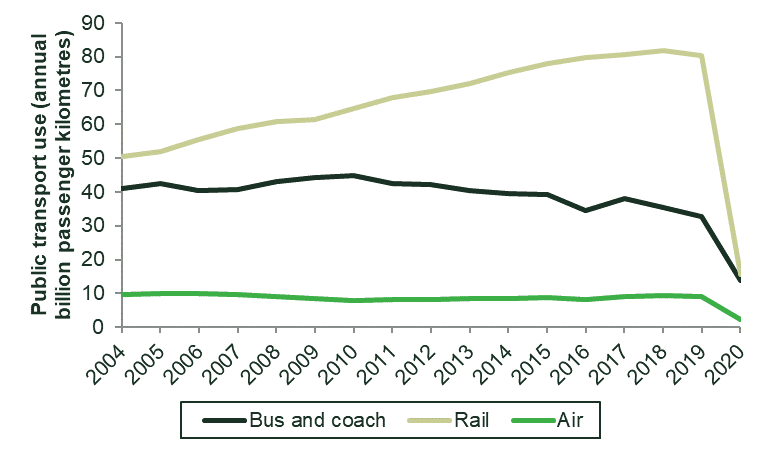

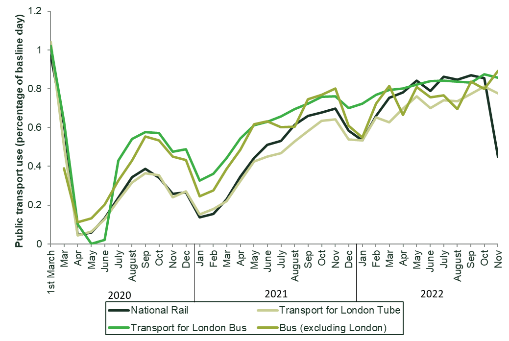

In addition, with cost escalation and public transport passenger growth either slowing or in decline pre-pandemic, the case for some enhancement projects already looked at risk. Post-pandemic, it is becoming increasingly clear that the impact of more working from home and fewer face-to-face business meetings has led to a permanent fall in public transport ridership. Potentially lower migration post-Brexit and a poor economic outlook mean that it will likely take a longer time for public transport demand to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Public transport growth was slowing pre-pandemic

Public transport ridership has not recovered to pre-pandemic levels

The combined impact of higher costs and lower demand for public transport will mean that the value for money of projects to improve public transport has worsened. From a portfolio perspective, there are likely to be some marginal schemes that once appeared to offer value for money but no longer do so.

A green opportunity

However, alongside these challenges, there is a burning platform for action. COP26 and COP27 have highlighted the need for more to be done by countries across the world to meet their commitments to decarbonisation.

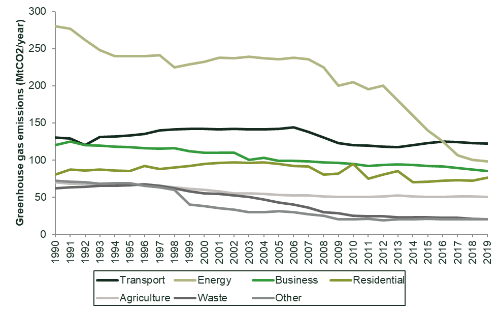

The transport sector is the biggest emitter of carbon, and it is the only sector in the UK to have seen little progress in reducing emissions since 1990. Air quality and other environmental issues are also increasingly rising up the political agenda.

Transport emissions as a proportion of overall greenhouse gas emissions have increased

The UK was the first to publish a Transport Decarbonisation Plan to decarbonise all modes of domestic transport by 2050.5 It is clear that only through substantial changes in travel behaviour, investment in public transport, and electrification across modes can the UK achieve its environmental obligations.

The combination of construction inflation, lower patronage and the overwhelming need for action on decarbonisation and environmental issues more generally means a new approach is necessary. Conventional transport interventions continue to have a role to play, but there will be fewer of these types of projects, as well as an increasing need to make the best use of existing assets we have.

Investment in innovation and new technologies in zero- and low-emissions transport will be key, and portfolios need to pivot towards these. Given short-run affordability issues, there is potentially a need to revisit the economic case for private financing. With less funding available to make public transport more attractive and relieve congestion, there is a growing need to reconsider ways to influence behaviour—with the case for road pricing and hypothecation into public transport looking increasingly strong.

The role of economic analysis

In this context, economic analysis is more important than ever when determining priorities for transport investment. Given the need to reappraise investment portfolios, economic analysis of the value for money and assessment of schemes against objectives should be a top priority.

In this context, there is also a case to think differently about how we appraise transport schemes. As Oxera Partner Andrew Meaney discussed in his recent paper to the European Transport Conference, the appraisal of benefits cannot be limited or biased by analysis ‘technology’ that can focus too much on the quantification of time savings.6

In line with the recent HM Treasury Green Book update, there needs to be greater focus on the strategic case for projects, and more weight should be given to unquantifiable benefits driving strategic objectives. Techniques such as multi-criteria analysis are effective tools in this type of decision-making.7

With decarbonisation being a binding legal requirement, there is perhaps a pressing case to adopt a marginal abatement cost lens to the transport budget and look at how to most effectively use the transport budget to achieve decarbonisation.

Given an uncertain outlook, the investment that is taken forward must also have a robust business case in a wide range of future scenarios—not just high- and low-demand scenarios, but scenarios encompassing a wide range of future possibilities of travel patterns, behaviours and technologies—and seek to be flexible to those changing circumstances.

The DfT recognises this challenge and last year released an ‘uncertainty toolkit’ to assist in the analysis of risk and uncertainty in investment appraisals.8 Other sectors, such as water, are going further, with Ofwat setting out a strategy of adaptive planning with ‘adaptive pathways [for] how decisions will be made under different plausible circumstances’, enabling flexibility in project delivery.9 A forthcoming Agenda article from Oxera Senior Adviser, Rupert Booth, will set out more detail on the important role of adaptive planning.

There is also a case to reassess how projects are financed if the transport budget will not stretch as far as is necessary to meet the UK’s ambitious objectives. Private finance is a tool that can potentially help to bridge this gap; this is particularly true of sustainable finance, where the door is clearly open to public-transport providers to support fleet decarbonisation. In doing so, there is a need to make the economic case for private finance and overcome concerns that private finance can be considered poor value for money, overly complex, or liable to fail to deliver on what is promised.

The time to act is now

Transport capital budgets have survived the cuts of the Autumn Statement, but future pressures may mean that this escape is short-lived. However, for the sake of the environment and transport’s role in maintaining it, the sector as a whole must see this as the emergence of a massive green opportunity. This point must be the catalyst to revisit investment strategies and pivot towards new approaches. Whatever the future holds, the role of economic analysis in supporting this change is clear.

1 Prime Minister’s Office, 10 Downing Street, Department for Transport, and the Rt Hon David Cameron (2014), ‘CBI Annual Conference 2014: Prime Minister’s address’, press release, 10 November.

2 UK Parliament (2020), ‘Prime Minister makes statement on transport infrastructure’, 11 February.

3 Office for National Statistics (2022), ‘Consumer price inflation rates’, October, last accessed 18 November 2022.

4 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022), ‘Monthly Bulletin of Building Materials and Components’, October, Table 1 and Table 2.

5 Department for Transport (2021), ‘Decarbonising Transport: A Better, Greener Britain’.

6 Oxera (2022), ‘Appraisal: the curse of numbers (and how to break it)’, prepared for the European Transport Conference 2022.

7 For further details, see Oxera (2021), ‘Investment appraisal in the round: why MCA?’, Agenda, 12 February.

8 Department for Transport (2021), ‘TAG: uncertainty toolkit’, 19 May, last updated 8 August 2022, last accessed 18 November 2022.

9 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR24 and beyond: Final guidance on long-term delivery strategies’, April.

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More