Show me the money! Will the proposed instant payments regulation change the way we pay?

The European Commission recently published a proposal on its regulatory approach towards instant payments, with the aim of fostering pan-European market initiatives. But will the regulation achieve its lofty objectives? We provide an economic assessment.

The European Commission has published a proposal on its regulatory approach towards ‘instant payments’1 (‘IPs’), which are bank credit transfers settled in real time.2 In the EU, the technical standard for instant payments is SEPA Instant Credit Transfer (‘SCT Inst’). The existing credit transfers that are not in real time are referred to as SEPA Credit Transfers (‘SCT’).

SCT, together with direct debits, are frequently used by households, such as when paying for utility bills, subscriptions, certain financial products, and when making donations to charity. However, these transactions are non-instant, therefore limiting the scope of their application: real-time settlement increases the range of their use case, potentially making them more attractive for ‘peer-to-peer’ payments (‘P2P’) or to smaller merchants. Acting as an ancillary feature on top of the basic infrastructure, overlay payment services can extend the scope of the use of credit transfers by increasing transaction security and convenience—for example, when purchasing products or services online.

The Commission’s objective is to ensure that anyone holding a payment account in the EU is able to receive and send an instant credit transfer within and across member states, in order to foster pan-European market initiatives based on instant payments.

The Commission’s proposal has identified a number of areas for regulatory intervention, and includes the following provisions.

- Mandatory acceptance: Payment Service Providers (PSPs) will be required to offer the services of both receiving and sending IPs in euro. For PSPs within the eurozone, the requirements will become effective in six and 12 months respectively, after the regulation comes into force.

- Pricing: the Commission requires that any charges applied for sending/receiving euro instant credit transfers within the eurozone should be no higher than the same PSP’s charges for a traditional credit transfer.

- Confirmation of Payee: the payer’s PSP is required to verify whether the payment account number and the name of the payee match.

- Requirement for screening: PSPs are required to verify at least once a day whether any of their customers are persons or entities subject to EU sanctions, and then block transactions where required.

This article discusses the economics of Instant Payments and overlay services, and evaluates the Commission’s proposals, based on an Oxera report commissioned by Mastercard (yet to be published).

Economic characteristics of payment services

Payment services bring together consumers who are able to make a payment and retailers and other recipients who adopt the means to accept payments. As such, payment services are a two-sided market serving two distinct types of users. Payees want to be able to accept payments within a system that payers are able to use, and vice versa.3

Credit transfers are characterised by the requirement for ‘universal reach’. Consumers expect to be able to transfer money to anyone with a bank account, and banks are unlikely to be successful if they can send credit transfers to only a subset of all the banks in a country (or the world).

Universal reach is driven partly by consumer expectations. For example, when using a mobile phone network, consumers expect to be able to reach anyone who has a mobile phone, irrespective of the type of network used.

Universal reach for credit transfers can be achieved by creating a common standard (for example, SCT and SCT Inst within the EU), and through a combination of interoperability between payment processing companies (so that banks using different processing companies can still reach each other), and some banks having access to multiple payment processing companies, which increases banks’ reach. Additionally, the PSD2 Open Banking provisions enable third parties (both banks and non-banks) to initiate credit transfers on behalf of current account holders, allowing for the development of overlay payment services by third parties. This increases the potential use case for instant payments.

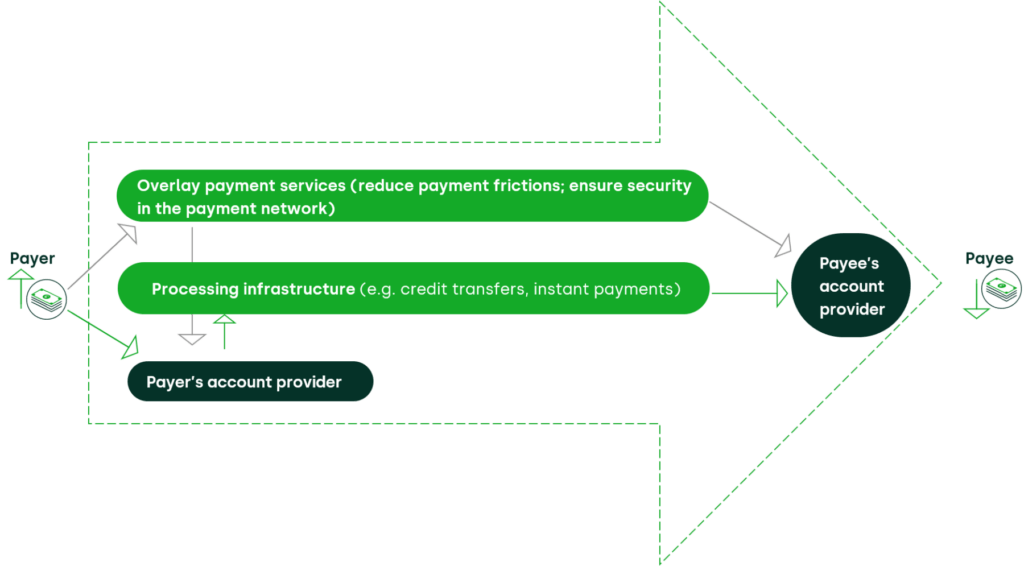

Figure 2.1 A payment method

Source: Oxera.

Importantly, while universal reach is required for credit transfers, it is not required for overlay payment services that run on credit transfers as the ‘rails’ (i.e. the underlying interbank infrastructure). Payment products such as Trustly, Sofort (now part of Klarna Pay Now) and GoCardless, which use credit transfer infrastructure as the ‘rails’, can be successful even if only some consumers hold them or only some merchants accept them—consumers and merchants can always switch to other payment methods. Figure 2.1 shows the two elements of a payment method: the overlay service and the processing infrastructure.

The economics of innovation

The different economic characteristics of credit transfers (including instant payments) and overlay services have implications for their incentives to innovate, with an important distinction between unilateral and collective innovations.

- Collective innovations require coordination between market participants. They are relevant to the system for credit transfers and can involve the adoption of a new approach across the whole industry, as is the case for the introduction of real-time settlement, with payment processing companies developing the technology and banks installing the relevant infrastructure. An industry would therefore only consider proceeding with an innovation if it passed the private cost–benefit case for each individual bank, even if the innovation were to be beneficial from the perspective of industry or society.

- Unilateral innovations can be brought forward by a single company, which bears the costs of innovation and receives the benefits. They are relevant to overlay services—payment products such as Trustly and PayPal are examples of unilateral innovation. Although some of the overlay services have been developed by the joint ventures of banks (such as Swish in Sweden and iDEAL in the Netherlands), the existence of various non-bank providers shows that bank ownership is not a requirement, and that overlay services can be developed unilaterally. The PSD2 Open Banking provisions have made this even easier by enabling non-banks to use the banks’ and processing companies’ infrastructure for credit transfers for payments.

In some cases, regulatory intervention may be required for collective innovation to take place, whereas unilateral innovation requires policy and regulation to focus on creating the right preconditions for a well-functioning market. In the case of overlay payment services, these include (for example) non-discriminatory access to the ‘rail’ infrastructure (as per PSD2 Open Banking provisions) and universal reach. It also requires a competitive market for instant payments by the banks—with competitive fees charged to consumers and merchants.

Mandating the adoption of SCT Inst

All PSPs in the EU offer traditional SEPA Credit Transfers to make and receive payments. So far, 70% have adopted the SCT Inst standard.4 However, there is significant cross-country variation, with this percentage being lower in some smaller EU member states.

When measured in terms of the number of current accounts (rather than the number of banks), the SCT Inst penetration is much higher, as larger banks have been quicker in making SCT Inst available to their customers.

Although progress has been made, the acceptance of instant payments is still far from universal, and some of the smaller banks in particular have been much slower in their adoption.

There are likely to be positive externalities from the adoption of instant payments by banks: the value to society derived from the development of instant payments and overlay services may be greater than that captured by each individual bank privately.

The European Commission has proposed mandating the adoption of instant payments across Europe, requiring all the PSPs that provide traditional credit transfers in euros to offer the ability to both send and receive IPs in euros.

Consumer protection

In response to the Commission’s consultation on instant payments,5 consumer bodies have called for more consumer protection measures in relation to instant payments, similar to the consumer protection offered by some debit and credit cards.6

It is worth clarifying that there are different types of risk associated with the payment for a product or service—some of which relate to the payment itself (human error or fraud), while others relate to the delivery or the condition of the product. In some sectors, such as the travel and leisure industry, there is also the risk of losing money if the company goes bankrupt before the service is provided. The risks that consumers face, and therefore the type and degree of protection that they might need, will depend on the type and context of the transaction. There is little that can go wrong when paying for a coffee in a café, whereas there are clearly risks when paying for an electrical appliance online.

Overlay payment services

Overlay payment services, such as Blik in Poland and Bancomat Pay in Italy, have addressed some of the risks with online payments. These services verify the identity of the recipient and automate the transaction by pre-filling the credit transfer form with the account name, number and transaction amount. Such transactions do not involve sharing sensitive account details and apply Strong Customer Authentication (SCA), reducing the risk of fraud.

Other payment methods based on credit transfers also offer protection in relation to the delivery of the product, and the product itself. For example, Klarna Pay Now, which uses credit transfers in combination with PSD2 Open Banking provisions to complete the transaction, offers a dispute-resolution mechanism and a buyer-protection policy covering non-delivery and defective goods.7 Another example is PayPal, which provides its own protection against undelivered or defective goods or services when transactions are funded using credit transfers or by direct debit.8

Finally, there are various marketplaces or platforms that offer buyer protection. For example, market places such as Amazon Marketplace and Etsy offer protection against damaged or undelivered goods, or goods that are not in line with how they were described. These examples show that market participants are already well-placed to develop consumer protection, and regulatory intervention may not be required at this early stage.

Payment scams

Credit transfers are not only used as the rails for overlay payment services, but also by households directly (i.e. without an overlay service)—for example, to pay utility bills, subscription services and memberships, and for certain financial products. Over time, some or many of these payments may be conducted using instant payments. The roll-out of SCT Inst may further increase the use of instant payments, such as for P2P payments and payments to smaller merchants.

Although the risks in relation to some of these payments are likely to be limited (such as in the case of P2P transactions and in-person payments to merchants where the product or service is received immediately), using credit transfers without overlay payment services may leave consumers vulnerable to misdirected payments. This may also increase the risk of payment scams, for example where fraudsters trick someone into sending a payment to a bank account controlled by the fraudster.

These risks can be addressed by the introduction of a Confirmation of Payee (CoP) service, as has been done in the Netherlands and some other countries. To prevent consumers from making a payment to the wrong bank account (by entering the incorrect account number or as a result of fraudulent activity or a scam), CoP checks whether the account name and number entered by the consumer match; i.e. it verifies that the name on the recipient account is the same person or business that they intend to send the money to, so that the funds end up in the right place.

The European Commission has now proposed that all banks offer such a service to their customers. Under the Commission’s proposal, if the account name and number entered by the consumer do not match, the payer is notified, but remains free to proceed with the transaction.

The introduction of a CoP service in the Netherlands and some other countries has been successful in preventing consumers from making a payment to the wrong bank account (either as a result of human error or fraudulent activity). It has resulted in an 81% reduction in fraud in payments to Dutch bank accounts, as well as a 67% drop in misdirected payments.9 Other countries are also looking to introduce CoP.10

Finally, to enable consumers to make choices about which payment method to use (for different types of purchases), it is important that consumers are informed about the risks of using credit transfers (without an overlay service), and more generally about the benefits of different types of consumer protection being offered. We note that the Commission’s proposals do not cover anything in relation to disclosure or consumer education.

Business models and pricing

Some overlay payment services are currently mainly national in their offering, in particular those set up by banks (such as iDEAL, Paydirekt, Blik, Bancomat Pay, Swish etc.), partly due to these banks having a pre-dominantly domestic customer base. However, non-bank providers such as PayPal, Trustly, Klarna and GoCardless have clearly demonstrated that it is possible to successfully enter and focus on a European or international market.

PSD2 Open Banking provisions have further lowered barriers to entry for payment methods based on the interbank infrastructure by reducing the need for active bank participation in a payments service. By getting direct access to a customer’s account, third-party providers are able to build services on top of banks’ existing infrastructure and can thus offer payment services across different EU countries.

Going forward, it is important that overlay service providers are free to choose the business model that suits them best, and that prices and fees are not distorted by regulatory intervention. Being able to set market-based fees provides the right incentives for new companies to enter, and for existing companies to continue to improve their service offering.

The same principles apply to instant payments. For banks to be able to successfully introduce instant payments and make these available to their customers, it is important that their pricing is not distorted by regulatory intervention, and that their efforts are adequately rewarded.

The payoff

Our economic assessment of the Commission’s proposal finds that it addresses the economics of instant payments and overlay services. Although progress has been made, the adoption of instant payments by banks is still far from universal. An increase in adoption of instant payments by banks is likely to facilitate the development of overlay services.

Banks and non-banks have introduced new retail payment methods by developing overlay services on top of the traditional SCT credit transfer system. Some of these providers have also developed buyer protection features, resulting in more choice and different value propositions for consumers and merchants.

Regulatory intervention at this early stage would therefore risk distorting the market and potentially crowd out commercial investments into new payment methods.

However, given the possibility for consumers to use credit transfers without overlay payment services, this could leave them vulnerable to misdirected payments and payment scams. In some countries, banks have successfully reduced these risks by introducing services such as CoP. This explains why the European Commission is now requiring all banks to introduce CoP.

1 European Commission (2022), ‘Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulations (EU) No 260/2012 and (EU) 2021/1230 as regards instant credit transfers in euro’, 26 October.

2 These exclude other forms of digital payments, such as card and e-money transactions.

3 For a more detailed analysis of the economics of payments systems, see Oxera (2020), ‘The competitive landscape for payments: a European perspective’, March.

4 68% of PSPs in the EU and 71% of PSPs in the eurozone have now adopted SCT Inst, which means that their customers can receive instant payments—many PSPs also allow their customers to send instant payments. See European Payments Council (2022), ‘Status Update on SCT Inst Scheme July 2022 ERPB Meeting’, 13 June, (accessed 3 August 2022).

5 European Commission (2021), ‘Targeted consultation on instant payments’, 31 March.

6 See, for example, Bureau Européen des Unions de Consommateurs (2021), ‘Consumers and Instant Payments – Answers to the Commission’s consultation on the content of a new legislation (07.04.2021)’, pp. 4–7.

7 See Klarna website in, for example: Germany, ‘Wie funktioniert Sofort bezahlen mit Klarna?’ and ‘Wir schützen dich.’; Italy, ‘Che cos’è Paga Ora?’; Spain, ‘¿Qué es Paga ahora?’; Belgium, ‘Payer avec Klarna.’

8 For transactions funded with credit transfers, the buyer protection is provided by PayPal, whereas for transactions funded by credit and debit cards, it is provided by the payment card company operator.

9 European Payments Council website (2022), (accessed 4 August 2022).

10 For example, The Nordic Payments Council has launched a public consultation on the Confirmation of Payee Scheme Rulebook, with the final version of the NPC Confirmation of Payee Scheme planned to be published in November 2022, and enter into effect on the same date. See Nordic Payment Council (2022), ‘Public Consultation on the NPC Confirmation of Payee Scheme Rulebook is now open’, April, (accessed 3 August 2022).

Download

Contact

Reinder Van Dijk

PartnerContributors

Related

Download

Related

Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers… Read More

Spatial planning: the good, the bad and the needy

Unbalanced regional development is a common economic concern. It arises from ‘clustering’ of companies and resources, compounded by higher benefit-to-cost ratios for infrastructure projects in well developed regions. Government efforts to redress this balance have had mixed success. Dr Rupert Booth, Senior Adviser, proposes a practical programme to develop… Read More