The GHG Protocol: measuring firms’ carbon footprints

Like a growing number of businesses, Oxera has made an explicit commitment to reducing our carbon emissions and becoming a net zero organisation. As part of this, we have estimated our annual carbon emissions using the most widely used method: the GHG Protocol. Carbon reporting is still in its infancy—so how well does the GHG Protocol work, and what behaviours might it incentivise?

As climate change has become increasingly important to citizens and policymakers around the world, attention has turned towards encouraging organisations to reduce their carbon footprints. As a result, carbon reporting has gained a lot of traction in recent years. Since 2019, listed companies, large unlisted companies, and large Limited Liability Partnerships in the UK have been required to report their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in their annual Directors’ Report. The UK government encourages all companies to voluntarily report their emissions.1

In 2022, both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the USA and the European Commission proposed new disclosure rules for public (and some private) companies that would require the reporting of some of their GHG emissions.2 This growth in regulatory interest in emissions reporting has been matched by growing consumer expectations around how brands should address their contributions to climate change.3

Despite this rise in demand for GHG reporting, research suggests that many businesses—potentially as many as nine out of ten small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the UK—remain unaware of their GHG emissions.4 Even when businesses do estimate their emissions, there is a wide range in the activities that they choose to cover,5 with the default being the emissions that are directly generated during the production of a business’s products. This mismatch between consumer and regulatory demand for emissions reporting, and the ability of firms to report on it, has created an increased need for a standardised toolkit in GHG accounting.

The most widely used methodology for carbon measurement is the GHG Protocol.

What is the GHG Protocol?

The GHG Protocol provides a standardised framework for measuring and managing GHG emissions from corporations, governments, cities and other bodies.6 The Protocol consists of a number of standards, two of which are the Corporate Standard and the Corporate Value Chain Standard (for simplicity, we refer to both as the ‘GHG Protocol’), which describe how companies should report their GHG emissions.

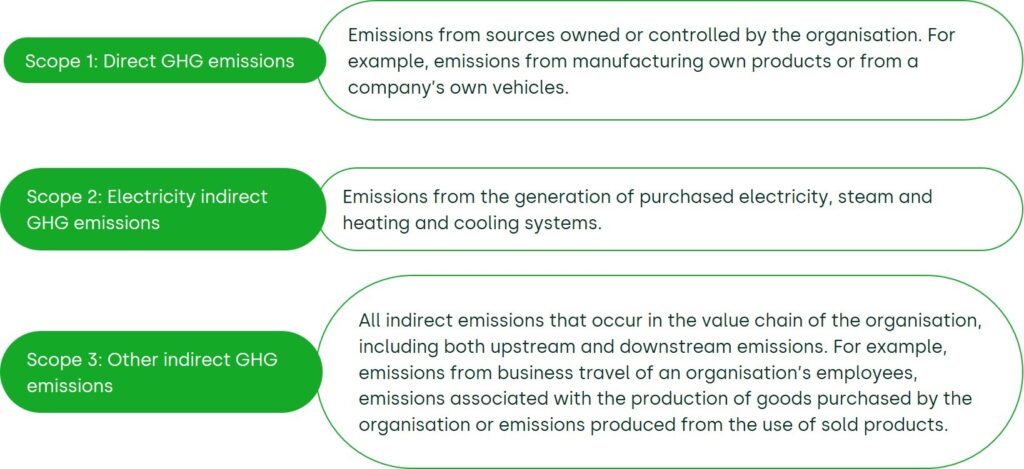

The GHG Protocol categorises emissions sources into three scopes, shown in Figure 1.7

Figure 1 Scopes of emissions in GHG Protocol

The GHG Protocol combines two GHG accounting methods in one: a production-based method (Scope 1) and a consumption-based method (Scopes 2 and 3). This combination means that there will be a double-counting of emissions when looking at the economy as a whole: Scope 3 emissions (and some Scope 2 emissions) of one company may be the Scope 1 emissions of another company. The rationale behind adopting this approach is to hold organisations accountable for their input choices and create incentives for organisations to decarbonise their supply chains.

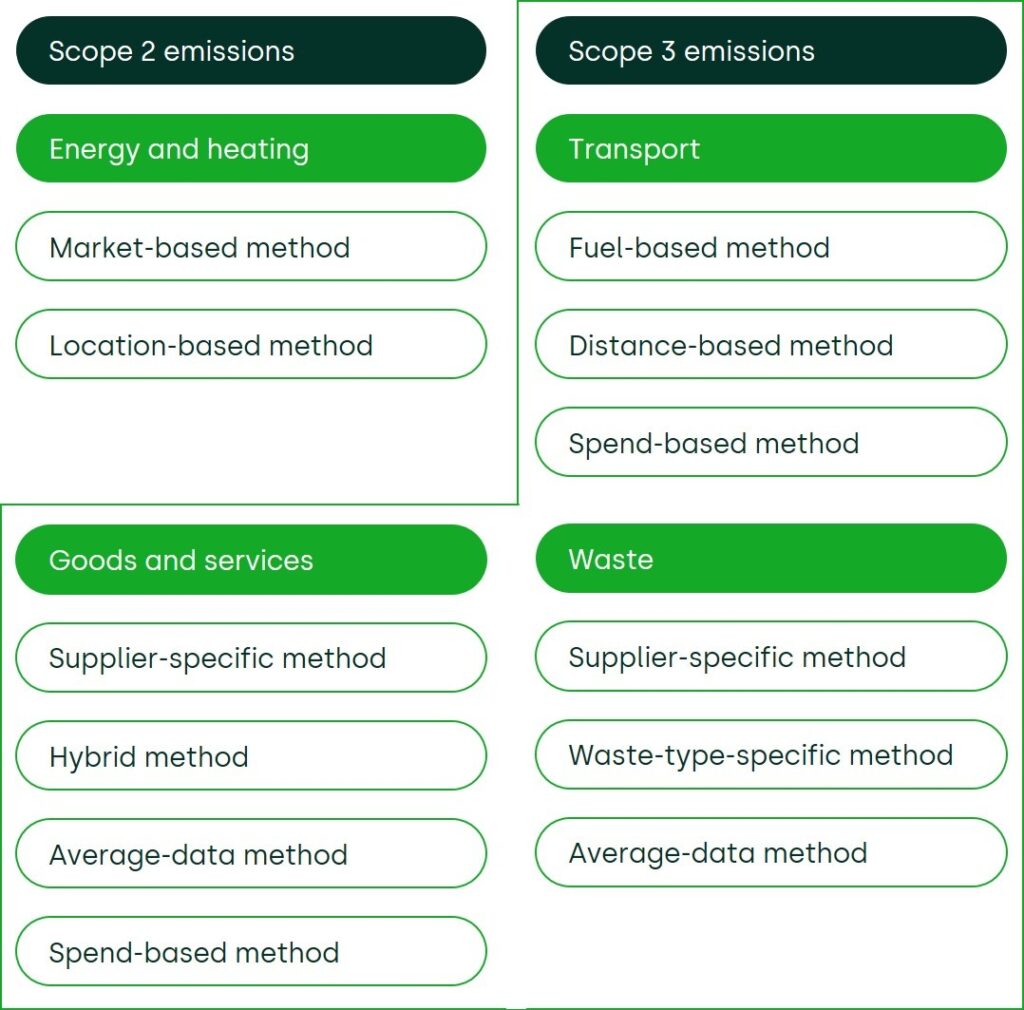

While the estimation of Scope 1 emissions is not trivial, it is simpler than the estimation of Scope 2 and 3 emissions as it only requires a company to understand its own processes in detail. The focus of this article is on the methods that the GHG Protocol provides for estimating Scope 2 and 3 emissions. A full list of the methods allowed by the Protocol is given in Figure 2 below, but the main types of approach that are approved are as follows.

- Scope 2 emissions: firms can report using either a market-based or a location-based method, where the former uses emissions data specific to the energy that they have purchased, and the latter uses the emissions implied by the energy mix in their location (which is usually defined at the national level).8

- Scope 3 emissions within the consumption of goods and services (including waste): emissions from purchased goods and services can be calculated using a supplier-specific method or a spend-based method. Supplier-specific methods use an emission factor9 based on the Scope 1 emissions reported by specific suppliers, while spend-based methods use emission factors that reflect the industry-average emissions intensity of a particular product. Supplier-specific methods are more likely to reflect the actual emissions of a given organisation’s supply chain. However, due to data availability, most firms are likely to use a spend-based method.

- Scope 3 emissions within transportation: the calculation of emissions from transport may use either a fuel-, distance- or spend-based method.10 Fuel-based methods require the organisation to keep track of the amounts of different fuels that it uses, and multiply these by a fuel-specific emission factor. Distance-based measures provide an emission factor for a particular type of vehicle, based on assumptions about the speed, fuel efficiency, and type of fuel that it uses. Spend-based methods are the most aggregated and use an emission factor that reflects the average emissions-intensity of travel expenditure, with different factors calculated for different transport types.11 Due to this, fuel-based methods are likely to be the most accurate, followed by distance-based methods, while spend-based methods are likely to be the least accurate.

Figure 2 Sources of emissions and their calculation methods

Source: Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2013), ‘Technical Guidance for Calculating Scope 3 Emissions’, April.

The GHG Protocol provides the basis for many national and international reporting requirements around the world. Of the Fortune 500 companies that report their emissions to CDP (a not-for-profit organisation that co-ordinates the global GHG disclosure system), 92% do so using the guidance set out in the GHG Protocol.12 The US and Canadian Climate Registry, the UK’s Voluntary Reporting Scheme, and the GHG reporting schemes of other countries such as Brazil and Mexico are all based on the GHG Protocol.13

Despite the wide use of the Protocol, there are a number of ways in which the current approach to the estimation of Scopes 2 and 3 may cause unintended consequences. The current approach may not always accurately reflect whether changes in the emissions intensity of a particular company have occurred as a result of actions that:

- the company itself has undertaken;

- reduce the amount of CO2 emissions relative to a situation where those actions would not have occurred (i.e. are truly ‘additional’).

What is ‘additionality’?

Economists typically quantify additionality as the extent to which an outcome is the result of a particular action, and would not have happened in the absence of that action. In the context of GHG emissions reporting, ‘additionality’ would occur if, when a firm reports a reduction in its GHG emissions, the total amount of global GHG emissions reduces by the amount that the firm has reported. Global emissions would be considered as they determine the level of warming. Therefore, if a reduction in one firm’s emissions were offset by an increase in another’s, there would be no net effect of the organisation’s actions on global warming.

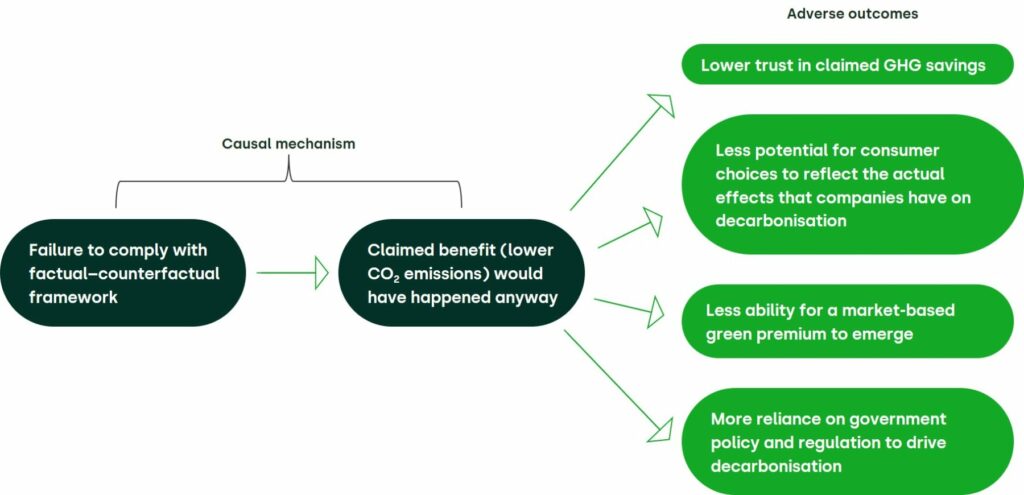

If the methodologies allowed by the GHG Protocol fail to comply with additionality, they may cause a number of unintended adverse social outcomes. These undesirable outcomes are depicted in Figure 3 below, which shows that, if companies can report their emissions as falling, when they would have done so even in the absence of some specific corporate actions, the following could occur.

- There is lower consumer trust in the claimed GHG emissions and GHG savings of companies.

- Consumers who want to make conscientious climate choices are unable to accurately identify which companies they want to make purchases from.

- As a result of both of the above, there is a lower likelihood that a green premium (i.e. a higher price that ‘green’ companies can charge for products) will emerge (because consumers are less willing to pay a premium to companies whose actions did not result in a reduction of global GHG emissions).

- If a green premium (i.e. a higher price than can be charged for low-carbon products) does not emerge, any decarbonisation that is more expensive than ‘business as usual’ will have to be driven by government policy and regulation. While this will be required anyway, it may be the case that if the market can achieve the same outcomes, then using the market as much as possible will be preferable (although this is an area where opinions will differ).

Figure 3 Adverse effects of failing to comply with the factual–counterfactual framework

What are the potential issues with the current approach to estimating Scope 2 emissions?

There are at least two reasons why the current approach to estimating Scope 2 emissions may not comply with additionality.

First, the GHG Protocol allows for the use of the ‘market-based’ method for calculating Scope 2 emissions. This approach allows a firm to estimate its level of GHG emissions based on the emissions that are embedded in the actual electricity that it purchases.14 For example, if a company increases the amount of ‘renewable’ electricity that it purchases, it can claim to have reduced its CO2 emissions.

At face value, this sounds like exactly the sort of behaviour that the GHG Protocol is trying to create incentives for. However, in practice the firm’s purchase of electricity that is defined as ‘renewable’ under the Protocol may have no, or limited, effect on the amount of CO2 that is emitted into the atmosphere. This is because the GHG Protocol allows for an organisation to define its electricity purchase as ‘renewable’ based on compliance with certain national schemes, and if these schemes are not consistent with the additionality framework outlined above, the organisation’s actions may have no impact on the levels of GHG emissions that it produces.

An example of such a scheme is the use of Energy Attribute Certificates (EACs), which the Protocol allows firms to use as evidence that their electricity was renewable.15 EACs are certificates that can be sold by renewable generators to electricity suppliers, in order to ‘prove’ that the purchased electricity is renewable. Therefore, if a company purchased 10GWh of electricity in a year from a supplier that has also purchased 10GWh of EACs, the company is able to claim that all of the electricity that it purchased was renewable.

However, if the price of an EAC is low, which historically it has been16 (although there is some evidence that this may be changing going forward17), purchasing the EAC is unlikely to have a material impact on an investor’s decision to construct a generator. In addition, once the renewable generator has been constructed, electricity is produced whenever the natural resource that powers it is available (i.e. when the sun shines, or the wind blows). These factors mean that, if the EAC price is low, neither the investment in the renewable generator, nor the production of electricity from the renewable generator, is dependent on the purchase of the EAC.

This historic lack of connection between the EAC and the quantity of renewable electricity in the grid has led organisations such as the UK government to state that ‘the assumed environmental benefit (quantified as kg CO2e) is likely to still be present in the system regardless of whether a customer selected the tariff’.18 In the context of the GHG Protocol, a firm may therefore believe that it has reduced its CO2 emissions when, even if it had not purchased the EAC, the CO2 emissions of the electricity sector would have been exactly the same.

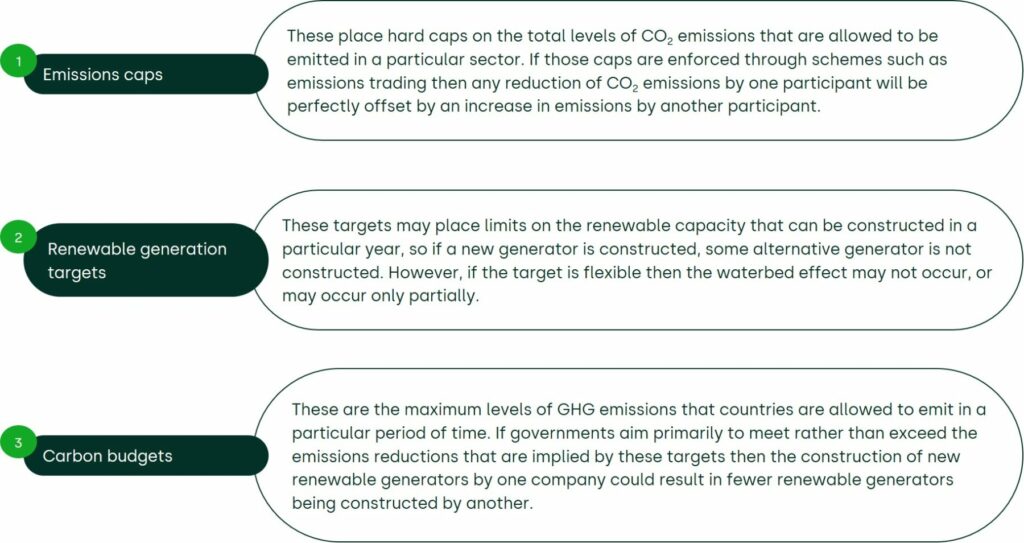

Second, the ‘waterbed effect’ could be present in the market for renewable energy, which could be a further reason why stated reductions of GHG emissions from the purchase of renewable energy occurred even in the absence of a firm’s actions. The waterbed effect refers to a scenario where the development of a renewable energy solution that reduces emissions in one area of a market results in a renewable energy solution being pushed out of (or undeveloped) in another area of the market. This effect could occur if the total amount of renewable electricity in the system is subject to a cap, meaning that, even if a corporate action results in the construction of a renewable project, it could be that some alternative project is not constructed. Figure 4 below explains the mechanisms through which the amount of renewable electricity in a system could be subject to a cap.

Figure 4 Mechanisms through which an effective cap could exist on the amount of renewable electricity in a system

The above means that some claims of GHG emissions reductions that are compliant with the GHG protocol may not have a ‘real’ impact on the sum total of GHG emissions, because they may not comply with the additionality framework.

What are the potential issues with the approach to estimating Scope 3 emissions?

Three issues arise from the Scope 3 methodologies that are allowed under the GHG Protocol. These include both generation of inaccurate measures of Scope 3 emissions and, relatedly, the knock-on effects that this has on the incentives that firms have to become greener.

First, the fact that organisations can choose which methods to use to estimate their emissions can cause the reported differences in emissions-intensity between more and less emissions-intensive firms to be lower than the true differences. Firms that purposefully purchase goods such as sustainable furniture (henceforth, ‘green’ companies) will have an incentive to use the supplier-specific method, as this will allow them to demonstrate the fact that they have purchased less GHG-intensive inputs in their reported emissions.19

Conversely, firms that have not taken an active interest in the emissions of their purchased goods and services (hereafter, ‘polluting’ companies) will have an incentive to report their emissions under the spend-based method. This is because the spend-based method uses emissions factors that reflect the average emissions-intensity of a given sector, and therefore any companies with above-average emissions intensity will appear ‘greener’ if they use the spend-based method than if they use a supplier-specific method.

However, as the actions taken by green companies will reduce the average GHG intensity of a particular upstream sector, the spend-based method will also show the polluting companies becoming less GHG-intensive. This will mean that the difference that consumers observe in the GHG intensities of companies that do and do not undertake upstream emissions-reduction strategies will be less than it really is.

Second, the data that is available for companies implementing a spend-based approach is typically highly generic and can therefore lead to inaccurate reporting. The data on the GHG Protocol’s website provides emissions factors for 15 sectors sourced from different countries, but the coverage of these remains limited as the industries concerned are narrowly defined (and in most cases the data is significantly out of date). For example, of the 15 sector-specific calculation tools available on the GHG Protocol website, each of which provides a set of emission factors, only one has been updated in 2022—the other 14 were published before 2016.20 While this issue can be resolved by companies undertaking their own analysis, or relying on third-party providers, to estimate their carbon-intensity such approaches are likely to be more expensive than using the readily available data. This effectively creates a barrier to the accurate reporting of emissions.

Finally, in the absence of supplier-specific data, organisations that make more environmentally sustainable choices may in fact report higher emissions-intensity than if they had not made environmentally sustainable choices. If a company calculates its emissions under the spend-based method, as many will have to do due to data availability, then its emissions will not be reduced even if they use ‘greener’ suppliers. In fact, if more environmentally friendly products command a green premium and are more expensive as a result, the purchase of cleaner goods will result in an increase in reported emissions, as a result of increased spend on suppliers. This will reduce the incentives for firms to procure more environmentally friendly upstream supplies, as doing so could make them appear less environmentally friendly.

Overall assessment of the GHG Protocol

Overall, the Protocol provides organisations with a clear approach to calculating their GHG emissions. It is also already widely known and used—allowing for a degree of comparability, and an industry that has already started developing in terms of calculating GHG emissions for firms. Therefore, there is a strong rationale for keeping large elements of the Protocol as they currently are.

However, our discussion above has highlighted two types of issue, relating to Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions. With Scope 2 emissions, the reliance of the current approach on external accreditation schemes for ‘renewable’ electricity can lead to companies claiming reductions in GHG emissions when these would have occurred in the absence of their actions. With Scope 3 emissions, we have identified that the current data used for estimating emissions may be inaccurate. While many firms that adopt carbon accounting will do so conscientiously, the spend-based approach could create incentives for companies to free-ride on the emissions-reduction strategies of their competitors, and some companies may therefore choose to follow this approach. They can also create some perverse effects whereby companies that undertake greener purchasing activity are perceived as less environmentally friendly.

The result of this is that the difference between the reported emissions-intensity of companies that are making major efforts to decarbonise, and those that are making lesser efforts, is less than the true difference in their emissions-intensity. Consequently, consumers may be less able to differentiate between the GHG-intensity of products, and may therefore have less trust in their reported GHG-intensity. Both of these factors would make it more difficult for a green premium to emerge that rewards companies for reducing GHGs. The decarbonisation of industry may therefore need to be driven more by policy and regulation than it would if GHG reporting were developed in a way that allowed for a stronger green premium to emerge.

The way forward

As we have discussed two separate issues in this article, there are two separate solutions that could be adopted.

First, with respect to the Scope 2 emissions, the GHG Protocol could be adjusted to ensure that the certification schemes that are permissible under the Protocol are compliant with the additionality principle. This could involve the Protocol being more selective in the certification schemes that organisations are allowed to use, restricting these to cover only those under which the renewable electricity that is purchased is genuinely incremental.

Second, with respect to Scope 3 emissions, governments could: require or encourage more organisations to report their Scope 1 emissions; and require organisations to use the supplier-specific method for measuring their Scope 2 and 3 emissions. By requiring all organisations to report their Scope 1 emissions, it would automatically become possible to use the supplier-specific method for all Scope 2 and 3 emissions (as one organisation’s Scope 2 and 3 emissions are just the sums of other organisations’ Scope 1 emissions). This would eliminate the need for the GHG Protocol to allow the use of the spend-based method, which is at the root of all of the issues that we outlined in relation to Scope 3 emissions reporting.

As a result, a system of GHG accounting could develop that could be integrated into accounting systems: if suppliers knew their Scope 1 emissions (as well as any Scope 2 and 3 emissions embedded in their product), they could include this in the invoice that is sent to their customer, and the customer could then input this into their accounting system.

Of course, the above proposals are somewhat idealistic, and in practice it may be difficult for the relevant stakeholders (the organisations behind the GHG Protocol and governments around the world) to agree on implementing these. However, this should not distract from the fact that these suggestions do present a possible way forward, and even partial achievement of these solutions should result in an improved system for GHG accounting.

1 HM Government (2019), ‘Environmental Reporting Guidelines: Including streamlined energy and carbon reporting guidance’, March, p. 5.

2 McKinsey & Company (2022), ‘Understanding the SEC’s proposed climate risk disclosure rule’, 3 June. Cooley (2022), ‘EU’s New ESG Reporting Rules Will Apply to Many US Issuers’, 28 October.

3 Deloitte (2021), ‘Consumers Expect Brands to Address Climate Change’, 20 April.

4 NatWest Group (2022), ‘9 out of 10 SMEs don’t know business carbon emissions’, 21 March.

5 Energy & Climate Intelligence Unit (2021), ‘Taking Stock: A global assessment of net zero targets’, March.

6 Greenhouse Gas Protocol, ‘About Us’ (accessed 16 December 2022).

7 World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2004), ‘The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard’, p. 25. World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2011), ‘Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard’, p. 28.

8 World Resources Institute (2015), ‘The Greenhouse Gas Protocol: A Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard’, p. 8.

9 An emission factor is an average amount of CO2e that is emitted for every pound spent on a certain product. Organisations can use a variety of emission factors, with some being specific to certain geographies, products and industries.

10 World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (2011), ‘Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard’, pp. 49–71.

11 Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2013), ‘Technical Guidance for Calculating Scope 3 Emissions’, p. 66.

12 Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2022), ‘GHG Protocol to assess the need for additional guidance building on existing corporate standards’, 31 March; CDP (2022), ‘Who we are’.

13 Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2011), ‘GHG Protocol: Looking Back on the Past Twelve Years’, 1 October.

14 World Resources Institute (2015), ‘GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance’, section 4.1.2’.

15 World Resources Institute (2015), ‘GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance’, section 10’.

16 For example, Guarantees of Origin (GOs)—the EACs that are issued in the EU—have historically traded at €0.05/MWh, less than 0.1% of the cost per MWh of constructing and operating renewable energy. Morais. M, Pinto. T and Vale. Z, (2020), ‘Adjacent Markets Influence Over Electricity Trading—Iberian Benchmark Study’, Energies, April, 52:11. European Commission (2020), ‘Final Report Cost of Energy (LCOE)’, p. 7.

17 BusinessWise Solutions (2022), ‘Article: REGOs Rising’.

18 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2020), ‘Designing a Framework for Transparency of Carbon Content in Energy Products. A Call for Evidence’, p. 24.

19 This situation is outlined explicitly in the Scope 2 guidance in Box 4.1: Greenhouse Gas Protocol (2013), ‘GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance’.

Related

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More