Adaptive planning: a proven solution in uncertain times

Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Consultation (SSMC) for the RIIO-3 price control in December 2023. Over the past three months, networks have been engaging with Ofgem to prepare their submissions as responses to the SSMC. In reviewing the SSMC, Oxera had noted1 the need to support ‘the pre-emptive construction of new infrastructure’.It stated:2

There is a risk that some of this will subsequently prove to be unnecessary, underutilised, of the wrong technology or in the wrong location—depending on how decarbonisation priorities and technologies (as well as their costs to deploy) evolve in the coming decade.

Oxera went on to state:3

gas networks face uncertainty around the extent and pace at which the pathway to decarbonisation will affect existing and new/enhanced network assets. The pace at which the GB energy system decarbonises, and the pathway that it takes, will affect when and whether assets are retained, repurposed or decommissioned.

This is a challenging backdrop for any price control. Although networks and regulators commonly undertake planning under uncertainty, and use probabilistic approaches for creating future forecasts, such forecasting approaches tend to presume knowledge of probability distribution functions and correlations between modelling parameters. And arguably, the modelling approaches for forecasting that have been adopted in the past are being challenged and extended to cope with higher levels of uncertainty: we are now in the realm of ‘deep uncertainty’.

Deep uncertainty has been defined as a situation:4

…where analysts do not know, or the parties to a decision cannot agree on, (1) the appropriate conceptual models that describe the relationships among the key driving forces that will shape the long-term future, (2) the probability distributions used to represent uncertainty about key variables and parameters in the mathematical representations of these conceptual models, and/or (3) how to value the desirability of alternative outcomes. In particular, the long-term future may be dominated by factors that are very different from the current drivers and hard to imagine based on today’s experiences.

The second point is especially relevant in an era when non-normal probability distributions with ‘fat tails’ are likely to be increasingly observed—i.e. with a greater-than-expected probability of extreme values than in a normal distribution.5

Adaptive planning—an approach which has been considered for dealing with deep uncertainty—has made the transition from the academic world to large-scale practical application. For example, it has been used as part of the PR24 price review in the water sector in England & Wales. Lessons from such planning processes and toolkits may have wider applicability in large-scale infrastructure projects, including for energy networks, as the RIIO-3 business planning process continues. Ofwat noted:6

Adaptive planning should be at the heart of the long-term delivery strategy. Adaptive pathways help to show what activities will be dependent on certain circumstances, and what is required in most or all plausible futures. This helps to optimise the profile of key interventions across time, ensuring that decisions are not avoided when they are needed, while minimising the risk of stranded assets.

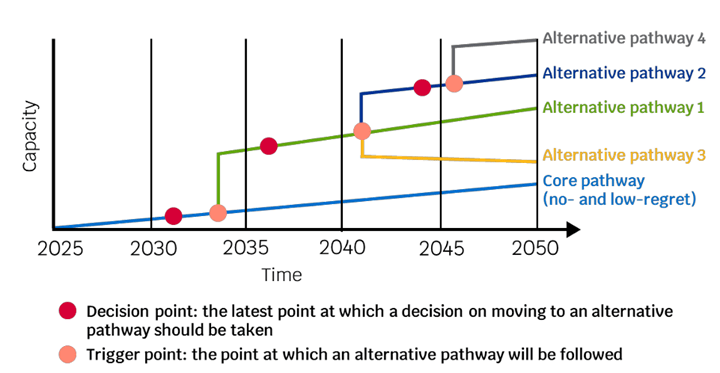

The planning process produces a core pathway of investments, and then proposes alternative pathways which could be triggered depending on how future uncertainties develop, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1 Illustration of core and adaptive pathways

Looking at adaptive planning in practice, the emerging patterns from the outcome of the water companies submitting their business plans including their Long Term Delivery Strategy (LTDS) are outlined below.

- The LTDS achieved their main purpose of aligning the next capital investment program (APM8) with a long-term vision for the company.

- The LTDS showed a consensus in relation to the need to increase the level of consumers’ bills, to fund necessary capital expenditure, although proposed phasing differed between the short and medium term.

- The LTDS highlighted some divergence of thinking within the sector, e.g. the priority given to increasing capital maintenance and the expected level of expenditure in relation to emerging contaminants to water quality.

- The LTDS also exposed differences in levels of service ambition up to the year 2050, as well as the rate of progress up to that point.

- In some cases, the difference in expenditure (and hence impact on customer bills) between the Scenarios7 and the alternative pathways was relatively minor8—however, this highlights differences in sensitivities and allows the water companies to focus their attention on key issues, in discussion with their stakeholders and Ofwat.

- Some of the more significant variations in expenditure arose from speculations on changes in government policy, which are not entirely exogenous to the companies at a sectoral level, as they have capacity to influence policy interventions.

Many of these insights arose or were evidenced as part of the LTDS exercise. By highlighting commonalities and differences between companies, this planning process revealed information in a format that permitted comparisons to be drawn across the sector, for a more informed discussion about future investment priorities in the water sector.

We note that the LTDS may be less useful for long-term forecasting of customer bills, not least given the potential for changes in government policy over time (e.g. in relation to the protection of vulnerable customers). However, they do at least highlight the tensions between asset health and service quality, and the politically sensitive issue of affordability—this tension has been observed in the recent past, where the impact of austerity may have contributed to the postponement of capital investment and maintenance.

There also needs to be awareness that the ’no regrets’ principle underpinning the core pathway will act to postpone expenditure until a use-case is established beyond reasonable doubt (except to keep options open). This may prove to be more costly to society in the long term, or incompatible with a regulator’s newly imposed growth duty.9

Similar benefits could be available in the energy sector if some of the tools from the LTDS approach were adopted. The variability of planning assumptions between companies would be revealed. Some of the assumptions would relate to exogenous events (broader than the current future energy scenarios relating to demand) and others to the companies’ own ambitions for capital maintenance and service levels. Where there are differences, the extensive commentary to the plans would reveal where the differences are explicable on the grounds of demographics, geography or installed asset base, for example. This would facilitate effective business planning and engagement with the regulator and/or policymakers.

Similarly, the impact of the timing of transition to net zero on affordability could be examined within the LTDS . As well as the affordability to customers, there is the parallel issue of the investability and financeability of the networks—the use of the LTDS to facilitate more effective dialogue between industry and the regulators/policymakers may lower the perceived risk to investors and facilitate the availability of capital.

In summary, adaptive planning has rapidly progressed from an academic concept to practical application, as seen by its sector-wide implementation in the water sector for PR24. The proven benefits of the LTDS exercise in the water sector suggests that it could have wider applicability, and bring value to planning processes for other large-scale infrastructure sectors, such as energy and transport networks—especially in regulated price control settings where medium- to long-term decisions about future investment are taken periodically.

1 Oxera (2023), ‘Ofgem’s RIIO-3 SSMC’, 21 December, https://www.oxera.com/insights/agenda/articles/ofgems-riio-3-ssmc/.

2 Oxera (2023), ‘Ofgem’s RIIO-3 SSMC’, 21 December, https://www.oxera.com/insights/agenda/articles/ofgems-riio-3-ssmc/.

3 Oxera (2023), ‘Ofgem’s RIIO-3 SSMC’, 21 December, https://www.oxera.com/insights/agenda/articles/ofgems-riio-3-ssmc/.

4 Lempert, R., Popper, S. and Bankes, S. (2003), ‘Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative, Long Term Policy Analysis’, RAND.

5 Marchau et al. (2019) cover several approaches to decision-making in more detail, and provide case studies of their use. See Marchau, V. A., Walker, W. E., Bloemen, P. J. and Popper, S. W. (2019), ‘Decision making under deep uncertainty: from theory to practice’, Springer Nature, p. 405.

6 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR24 and beyond: Final guidance on long-term delivery strategies’, p. 6.

7 There are eight reference scenarios, with benign and adverse consequences for are: climate change, technology, demand and abstraction reduction., with the options for a company to devise their own scenarios

8 This observation is based upon analysis of the data tables LS5, LS6 and LS7 for every LTDS.

9 Department for Business and Trade (2024) ‘Smarter Regulation: Regulating for Growth Consultation’

Related

Allocation of indirect costs

There is no right or wrong way to allocate indirect costs, only good or bad ways of supporting policy objectives, either of the company itself or an industry regulator or competition authority. This article reviews the many allocation options, before proposing a process for selecting the most promising option… Read More

Grey or Green Giants? Sustainability and (Exclusionary Abuse of) Dominance under Article 102 TFEU

The intersection of sustainability and competition law has gained increasing attention in recent years—particularly in the context of agreements, as evidenced by the new Horizontal Co-operation Guidelines from the European Commission,1 but also in discussions around merger control.2 However, one area remains underexplored: the role of… Read More