Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for rail services. Our first article examined the high-level options for regulating GBR (self-regulation vs independent regulator), by considering how the proposed industry structure differs from the status quo. In this second article we explore three specific challenges that arise from rail reform, and which regulation will need to address.

These challenges relate to the following areas, which we address in turn:

- efficiency and risk;

- competition;

- focus on passengers.

Efficiency and risk

As discussed in our first article, the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) or another independent body may have a role in regulating GBR, including by setting appropriate performance and efficiency targets. Alternatively, if GBR were to self-regulate, it will need to provide assurance to Government that it is efficient and delivering to its performance targets. Doing this will require assessing the efficiency of both GBR’s infrastructure management and service provision. As such, the ORR’s current approach to benchmarking cost efficiency will need a substantial update, given the present arrangements only focus on the former.

Importantly, assuming it is part funded via farebox revenue earned from passenger services, GBR will be subject to a new major source of financial risk. This is because, unlike the relatively stable income earned from Track Access Charges (TACs), farebox revenues are far more volatile and difficult to predict. This will materially complicate any assessment of what GBR should be expected to deliver with a given public funding envelope, since this would now require an assumption of the efficient amount of farebox revenue it should be expected to earn (as well as assessing GBR’s cost efficiency).

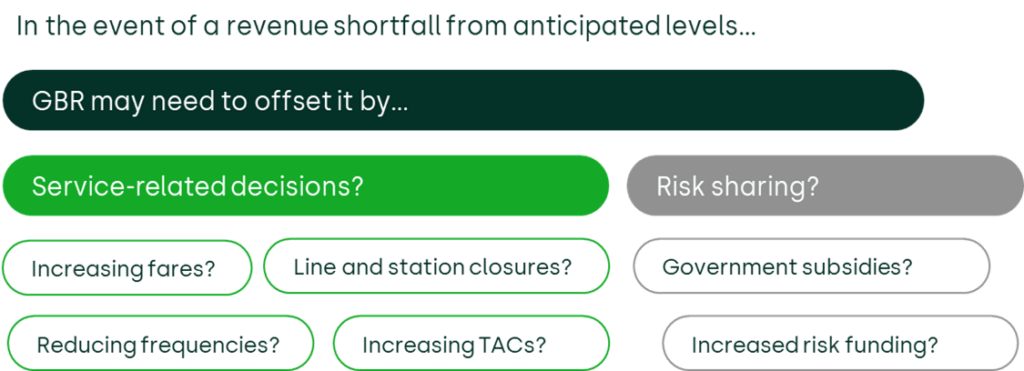

If—once the control is set—farebox revenue falls short of expectations, GBR may find itself facing a significant funding shortfall.1 To bridge this gap, it may need to consider difficult options, such as cutting or reducing services, raising TACs, or increasing fares. Alternatively, the government might have to step in and cover the shortfall.

Figure 3 GBR’s array of decision options in the event of a revenue shortfall

In this context, the Department for Transport (DfT) and HM Treasury may need to consider introducing a new risk sharing model, which provides for considerably greater contingency than is currently made available to Network Rail via the periodic review process. Alternatively, it may be possible to implement risk-sharing mechanisms, such that GBR shares financial risk with the Treasury or other regional funders. However, such protections may diminish incentives. After all, the more protection GBR receives, the less motivation it has to operate efficiently and deliver high-quality services. Striking the right balance between financial support and operational accountability will therefore be essential.

Competition

Under the new model, the Secretary of State will set GBR targets for growing rail freight and GBR will have a duty to enable this growth.2 The stated policy is also that open access operators will retain a significant role in the network, as long as they can ‘add value and capacity’.3 It remains unclear whether future policy will promote or restrict the entry of non-GBR-run services.4 What is clear, however, is that the introduction of a vertically integrated GBR presents competition risks to open access and freight operators, which the regulatory regime will need to address.

The first issue relates to cost accounting. More specifically, if GBR produces integrated regulatory accounts and receives a single (or various regional) funding settlement(s) (covering both infrastructure and services), non-GBR operators will need assurances that the TACs they pay do not reflect costs which GBR should bear itself. Clear cost-accounting rules are needed, enforced by a regulator, to minimise the risk of disputes between non-GBR operators and GBR.

The second risk relates to the potential for ‘margin squeeze’. This could occur in a context where an open access operator launches a new service somewhere on the network, which competes against a GBR-run service (potentially indirectly). GBR—having control of fares—could respond by lowering prices. In most cases, this reduction in fares can be considered a rational response, which ultimately benefits consumers through lower prices in the long run.

An issue arises, however, if the incumbent operator—in this case GBR—sets fares below its own costs in an attempt to drive out competition, increasing its market power. This would enable them to then raise prices, and therefore (at least) recover the losses incurred during the period of the margin squeeze. Such a strategy could leave consumers worse off in the long run, even if they benefitted from lower prices in the short term.5

How can these risks be managed? One solution to the cost-accounting issue could be to require two separate accounts from GBR: one for infrastructure, and one for operations. Similar approaches have been used in fixed-line broadband regulation, to ensure that incumbents refrain from recouping costs incurred by servicing one part of the network from users consuming services on another part of the network.6 The key here would be to strike a balance between transparent cost allocation while preserving the overarching goal of GBR—namely, to reap the benefits of joint decision-making between infrastructure and operations.

Alternatively, addressing the risk of margin squeeze might be achieved by implementing a ‘margin squeeze test’. This would assess whether the gap between wholesale and end-user prices is large enough to enable profitable entry and expansion, or whether the gap is so narrow that it squeezes margins to such an extent that competitors would be foreclosed from the market. In this context, the aim would be to establish whether, given:

- the price of the wholesale input (in this case, TACs);

- the costs of delivering the downstream service (i.e. the passenger service);

an ‘efficient’ operator would be able to cover its costs, including earning a reasonable profit margin.7

Whatever the solution, either the government and/or an independent regulator needs to be clear about how costs should be allocated and how fares should be set. Clear guidelines would help minimise the risk that pricing and cost-allocation strategies tip the scales in GBR’s favour.

Focus on passengers

In theory, a single GBR should provide significant advantages to delivering passenger services. It means infrastructure decisions and service operations can be tightly integrated, making coordination between track and train operators smoother and more efficient. But, as with any major shake-up, there are trade-offs that need to be carefully managed.

Infrastructure projects—be they enhancements, or renewals to the existing network—tend to be costly and demand long-term investments. When these projects are on the table, there is a risk that GBR’s budget could get pulled away from the day-to-day needs of passenger and freight operations, shifting focus to infrastructure spending instead. And while those capital projects usually bring long-term benefits, they could end up overshadowing more immediate, short-term demands—like ensuring that trains are running on time, services are reliable, and passengers’ needs are met today, not just in the distant future.

This highlights the importance of having independent oversight of GBR, particularly in the design of the Passenger Standards Authority. Oversight is crucial to ensure that GBR stays accountable, but it is also important to avoid micromanagement. GBR needs the flexibility to fulfil its duties through the regulation of the delivery of outputs, as opposed to choices made along the way.

It may, therefore, be useful to explore mechanisms employed in other sectors to help ensure that the user voice is reflected in decision-making. One such example is the energy sector, where Ofgem has required that each regulated company set up an Independent Stakeholder Group (ISG). Each company’s ISG provides challenge and scrutiny as the company develops its five-year business plan, and on an enduring basis in the delivery of its plan. The intention is that the ISG represents the interests of consumers and stakeholders, playing an important role in holding the company to account.8 A similar approach could be adopted within GBR at the regional level, allowing ISGs to represent local consumer interests and hold GBR accountable for delivering on its commitments.

There are also other notable examples of collaborative decision-making that promote transparency and consensus among stakeholders. In the UK aviation sector, for instance, the Heathrow Community Engagement Board (HCEB) was set up to give local communities a formal platform to engage regularly with the airport on issues like noise, air quality, and expansion plans.9 Another angle of policy to learn lessons from is the Financial Conduct Authority’s Consumer Duty, which evaluates whether firms’ decisions lead to the right outcomes, ensuring that they prioritise customer needs in their decision-making processes. Applying this to the rail context, a consumer duty would require GBR ensure that passengers choose the right ticket for their needs, offering the right combination of price and journey time.

Looking ahead

The planned overhaul of the rail industry promises transformational change, but achieving this will require getting the regulatory framework right. The good news is that we are still in the early stages of the market design process, meaning that there is plenty of room to address these challenges head-on and shape a framework that balances the needs of all stakeholders.

Importantly, the regulatory issues arising from rail reform are not confined to Great Britain’s rail sector. Other industries have faced similar challenges and found creative, workable solutions—so there is no reason why the rail sector cannot follow suit. By drawing on lessons from other sectors and countries, there is a real opportunity to develop a system that ensures transparency, promotes fair competition, and facilitates accountability. With careful planning and smart regulation, GBR could be the fresh start the industry needs—one that delivers a better, more reliable railway system for everyone involved.

1 We say ‘may’ because if GBR is able to outperform the regulator’s cost-efficiency assumptions, then—at least in theory—this might offset the farebox revenue shortfall.

2 Labour Party (2024), ‘Getting Britain Moving: Labour’s Plan to Fix Britain’s Railways’, p. 19.

3 Department for Transport and The Rt Hon Louise Haigh MP (2024), ‘Establishing a Shadow Great British Railways’, 3 September.

4 The ORR has issued guidance on assessing track access applications for open access operators and is consulting with industry on a proposal to establish a standard method for monetising the costs and benefits linked to such applications. It remains uncertain whether the government plans to adopt this approach for future open access applications or develop a distinct method. See Office of Rail and Road (2024), ‘Summary guidance on rail open access applications’, September.

5 It should be noted that such a strategy may be profitable even if the competitor is simply ‘marginalised’, but does not entirely exit the market.

6 This is formally referred to as ‘accounting separation’, which is a requirement for a vertically integrated undertaking to draft a profit-and-loss account per market, in order to verify the lack of discrimination or unfair cross-subsidy. For more details, see (for example) Belgian Institute for Postal Services and Telecommunications website, ‘Accounting Separation’, accessed 16 October 2024.

7 This raises a question of how to define an ‘efficient’ operator for the purpose of the margin squeeze test. For more details, see Oxera (2009), ‘No margin for error: the challenges of assessing margin squeeze in practice’, November.

8 Ofgem (2024), ‘RIIO-3 Business Plan Guidance’, p. 7.

Contact

Robert Catherall

PrincipalContributors

Related

Related

A fast and low-risk solution to the growth problem?

Small innovative companies face a significant equity shortfall. If this shortfall could be reduced substantially, these companies would materially increase national productivity and growth. But the regulations which contributed to the shortfall are well-founded. Simply reducing or reversing these regulations would likely impose high social costs. The regulations are diverse… Read More

ESG: does the political shift mean businesses will lose out?

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles have long been a key factor in Boardroom discussions and decisions. However recent political developments—particularly in the US—have sparked a stark change in direction. Is it all over for ESG, or is there a future? In this episode of Top of the Agenda,… Read More