Brexit: implications for state aid rules

State aid rules are an important consideration in a broad range of business activities across all EU member states. In the UK, a number of high-profile cases have come under public scrutiny because of potential state aid issues (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 State aid issues in the UK: selected examples of recent cases

Source: Oxera.

With the UK poised to vote on its future EU membership, Brexit could have a significant impact on state aid rules and their implications for regulating business activities in the UK. Any impact would largely depend on the type of post-Brexit arrangements the UK negotiates with the EU. The two potential outcomes that are likely to materialise in such a situation are:1

- Brexit with negotiated free trade agreement: in this scenario, the UK has a special agreement with the rest of the EU and continues to participate in the single market as a member of the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) joining Norway, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Switzerland;

- Brexit without any free trade agreement: the UK does not have any special free trade agreement with the rest of the EU, and is bound by World Trade Organization (WTO) rules.

For businesses operating in Scotland, there is an additional layer of uncertainty, with the potential for Scotland to join the EU as an accession state if it decides to gain independence from the rest of the UK.

An overview of the state aid framework (see the box below) and the implications of these scenarios are explored in further detail in this article.

Overview of the state aid framework

As a member of the EU, the UK is currently subject to state aid rules. These rules are designed to monitor and restrain selective measures by the state that threaten to distort competitive forces in the EU market.

The European Commission defines state aid as:

an advantage in any form whatsoever conferred on a selective basis to undertakings by national public authorities.1

A measure constitutes state aid if it:

- involves the transfer of state resources;

- has potential distortive effects on competition and trade in the EU market; and

- confers a selective economic advantage to the recipients.

Such measures can take a variety of forms, including grants, subsidies, loans, guarantees, and tax credits. However, not all state aid is unlawful. If the aid contributes positively to the EU economy without having an undue negative impact on competition, then under certain conditions, the aid would be lawful. The European Commission defines this as ‘compatible aid’, which can have important economic benefits, leading to increased employment and output.

A report by Oxera for the European Commission concluded that employment at the industry and regional level falls substantially when firms in financial difficulty do not receive rescue or restructuring aid. At the firm level, employment generally falls by around 30% whereas output falls by almost 20% over the three years post-distress.2 Similarly, a study on regional assistance programmes in the UK found that a 10% increase in state subsidies led to a 7% increase in manufacturing employment in the region where the aid was granted.3

Source: 1 Article 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. 2 Oxera (2009), ‘Should aid be granted to firms in difficulty? A study on counterfactual scenarios to restructuring state aid’, prepared for the European Commission, December. 3 Criscuolo, C., Martin, R., Overman, H. and Van Reenen, J. (2012), ‘The Causal Effects of an Industrial Policy’, National Bureau of Economic Research.

What might the future state aid framework look like?

Exit with free trade agreement

If the UK negotiates a post-Brexit free trade agreement with the rest of the EU, the state aid framework will depend heavily on the details of the free trade agreement:

- if the UK joins the European Economic Area (EEA). If the UK joins Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein as a member of the EEA, the UK will be bound by the EEA Agreement, which replicates EU rules on competition law. State aid activities will be governed by the EFTA Surveillance Authority under a framework that is very similar to the European Commission’s existing framework;

- if the UK joins the EFTA, but not the EEA. If the UK joins Switzerland as a member of the EFTA, but not the EEA, the UK will no longer be bound by the EEA Agreement and therefore will not face equivalent state aid rules. In this case, the outcome for the state aid framework will be more uncertain. For example, Switzerland has a bilateral agreement with the EU on state aid in aviation, but broader state aid rules that govern the rest of the EU and the EEA are not applicable;2

- if the UK does not join the EFTA, but has a separate free trade agreement with the EU. If the UK enters into a separate free trade agreement with the EU similar to Canada’s Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) which does not contain any specific state aid provisions, then the UK would no longer be bound by state aid rules. The impact on UK and EU businesses would be similar to the scenario where there is Brexit without a free trade agreement.

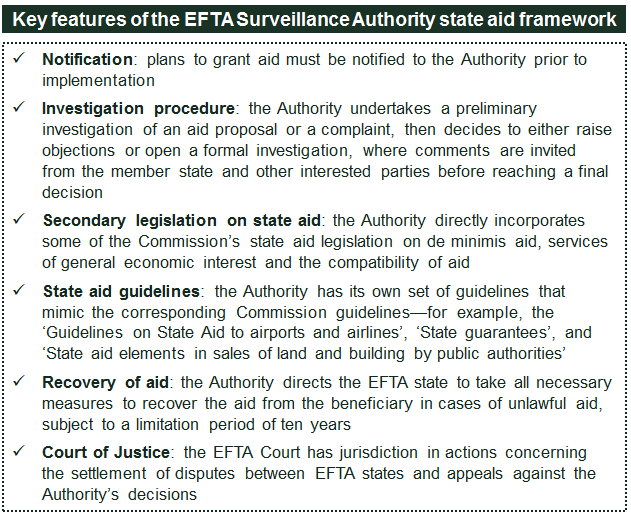

It is plausible that EU member states could insist on the UK adopting equivalent state aid rules in order to maintain a level playing field thereby encouraging competition and productivity leading to economic growth. Therefore, it may be considered more likely that the UK would join the EEA, and would be governed by the state aid rules adopted by the EFTA Surveillance Authority. As highlighted in Figure 2, these rules are very similar to the European Commission’s existing framework.

Figure 2 Key features of the EFTA Surveillance Authority’s state aid framework

Source: EFTA Surveillance Authority’s website, accessed 8 April 2016.

Therefore, from a state aid perspective, Brexit is unlikely to have significant economic implications for businesses, if the UK joins the EEA.

However, Brexit with a free trade agreement could lead to greater legal uncertainty for UK companies (both beneficiaries and complainants of state aid), for several reasons:

- the EFTA Surveillance Authority has significantly less experience in state aid than the European Commission, as it governs state aid rules in only three member states compared with 28 member states for the European Commission;

- the process of challenging state aid decisions in Courts is less developed, since there is only one EFTA Court for the EEA, compared with two Courts in the rest of the EU—the General Court and the European Court of Justice;

- the UK would have less influence on the development of state aid rules going forward;

- if the European Commission’s ongoing investigations were to be handed over to the EFTA Surveillance Authority post-Brexit, UK companies affected by pending state aid cases would face greater uncertainty during any transitional period.

Exit without free trade agreement

If the UK did not agree any special trade arrangements with the EU post-Brexit, the UK would be bound by WTO rules; however, these rules are narrower in scope compared with EU state aid rules.3

Under WTO rules, the Dispute Settlement Body of the WTO can impose actions such as the withdrawal of the subsidy or its adverse effects. However, unlike the European Commission’s state aid framework, there is no procedure under which subsidies or other forms of state support are notified and approved by the WTO.

Instead, the implementation of the rules relies on ex post dispute settlements without any retrospective recovery of unlawful aid. Under the WTO regime, only member states are responsible for enforcement—private parties are not able to take action against measures that harm them.4 This scenario could lead to new local legislation for implementing state aid rules within the UK.

Impact on UK businesses

Brexit without any free trade agreement could in principle allow for higher levels of state funding in the UK. For example, the UK government could intervene and provide state support to assist the Port Talbot steelworks without being constrained by EU rules.5

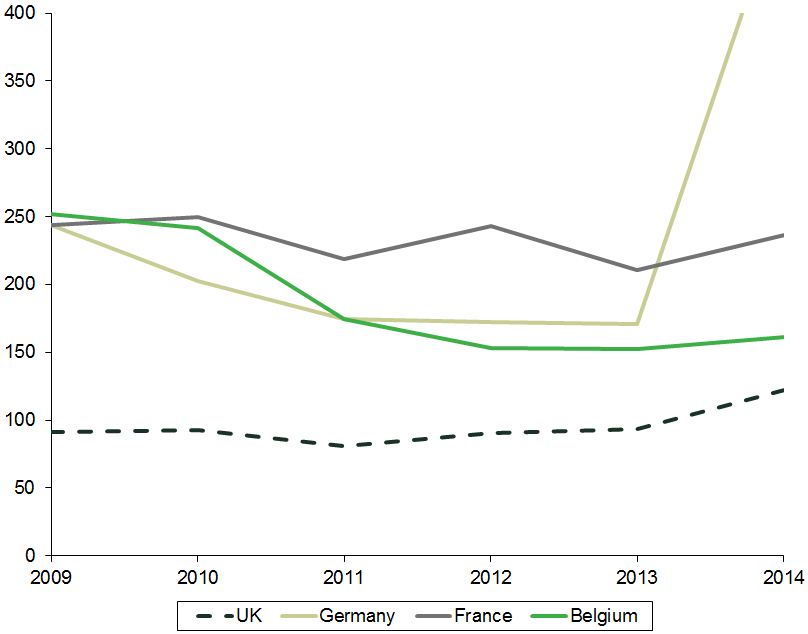

However, the UK has traditionally provided levels of aid per capita that are much lower than those seen in other European countries. For example, as shown in Figure 3 below, the average amount spent by the UK on aid is approximately €90 per capita compared with €170–€240 per capita in Germany, France and Belgium. Therefore, the absence of the EU state aid framework might not necessarily translate into significantly higher levels of public investment.

Figure 3 Comparison of non-crisis state aid per capita (€)

Note: Non-crisis state aid excludes aid granted to financial institutions during the financial crisis between October 2008 and October 2014. Due to the lack of availability of data over the period under consideration, aid on railways is excluded from the figure. The significant increase observed in the amount of state aid per capita granted by Germany in 2014 is due to an increase in the aid granted for environmental protection and energy saving activities. This is likely to be driven by the adoption of the European Commission’s Energy and Environmental Aid Guidelines in 2014, which led to greater awareness on the inclusion of renewable energy support schemes in the reporting of state aid measures by member states.

Source: Oxera analysis, based on European Commission State Aid Scoreboard 2015 and population data from the World Bank.

As the UK has tended to give less state aid than other member states, state aid rules typically assist UK businesses, by controlling illegal aid to competitors in other member states and requiring illegal aid to be repaid.6

UK businesses could also potentially lose their ability to receive compatible state aid from other EU member states.7 Moreover, UK businesses would no longer have a reliable mechanism to complain to the European Commission or challenge European Commission decisions regarding aid by member states to other companies in the EU, even if they are being disadvantaged by such aid. For example, a UK company currently receiving EU funding to support its R&D activities would lose this funding. In addition, although the UK company could bring information to the European Commission about any illegal state funding provided to its EU competitors, there is no particular incentive to act upon this information.8 Therefore, the UK company would be at a competitive disadvantage.

Impact on Scottish businesses

The outcome for Scottish businesses will also depend on whether Scotland chooses to remain in the UK post-Brexit or if it chooses to gain independence from the rest of the UK and joins the EU as an accession state.

If Scotland stays in the UK, the governing state aid framework and the consequent impact on Scottish businesses will be similar to those described above for UK businesses. However, if Scotland stays in the EU but out of the UK, it will still be bound by the European Commission’s state aid framework and the consequent impact on its businesses will be similar to the impact on businesses in the other EU states, as described below.

Impact on other EU businesses

In the event of Brexit without a free trade agreement, the absence of stringent state aid rules in the UK could attract businesses in other EU states to move a part of their operations to the UK, where they could potentially receive aid from the UK government. EU businesses would also not be able to challenge any aid given by the UK government to their UK competitors.

Conclusions

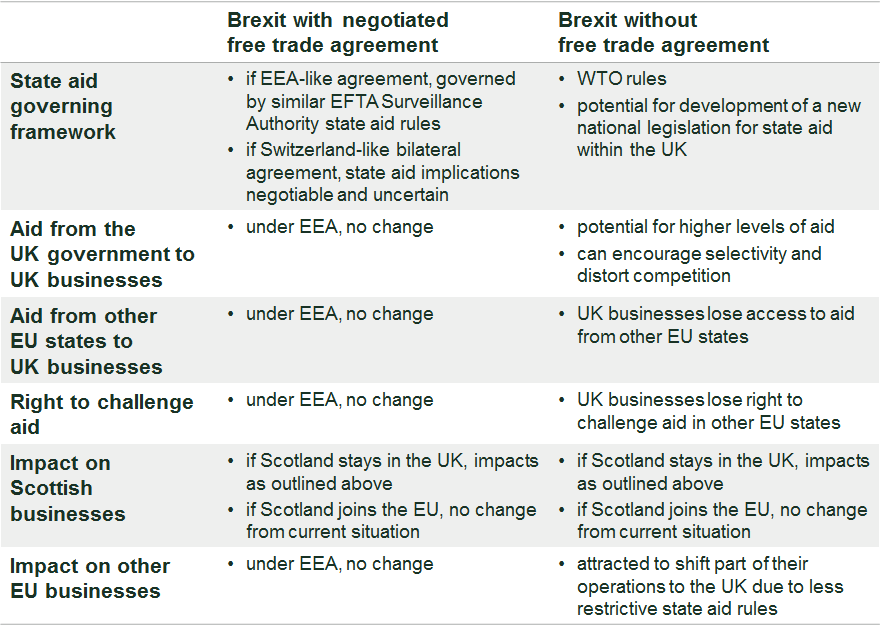

The overall implications of Brexit on state aid issues are summarised in Table 1 below.

Table 1 Overall implications of Brexit from a state aid perspective

Source: Oxera.

1 Centre for European Reform (2014), ‘The economic consequences of leaving the EU: The final report of the CER commission on the UK and the EU single market’, June.

2 This agreement came into effect in 2002 as a result of Switzerland’s desire to accept EU legislation in this area to maintain competitiveness and to secure Switzerland as a key business location by ensuring access to European airspace. For further details, see Zurkinden, P. and Scholten, F. (2004), ‘State Aids in Switzerland: The Air Transport Agreement between the EU and Switzerland’, European State Aid Law Quarterly, 3:2.

3 The Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (‘SCM Agreement’) notes that measures such as capital injections, loans and guarantees from the state ‘which distort or threaten to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods’ are considered a violation of the agreement. For further details, see World Trade Organization, ‘Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures’, accessed 13 April 2016.

4 For a comparison between the European Commission’s state aid rules and the WTO mechanisms, see Ehlermann, C.D. and Goyette, M. (2006), ‘The Interface between EU State Aid Control and the WTO Disciplines on Subsidies’, European State Aid Law Quarterly, 5:4, p. 695.

5 This would still be subject to WTO rules on state subsidies, but these are less stringent relative to EU state aid rules.

6 For further details, see HM Government (2014), ‘Review of the Balance of Competences between the United Kingdom and the European Union. Competition and Consumer Policy Report’, Summer.

7 For businesses that are already receiving some form of aid from other member states, this outcome could mean a loss of funds, unless the UK government were to proactively step in to replace the funding.

8 Simmons & Simmons (2016), ‘Brexit: implications for State aid law’, 23 June.

Download

Related

Company valuation in post-M&A disputes—the Mahtani v Atlas Mara ruling

Post-merger and acquisition (‘post-M&A’) disputes can take many different forms, such as breach of representations and warranties, fraud and misrepresentation claims, and post-completion breach of contractual obligations. This article discusses the valuation issues in a post-completion breach case based on the ruling handed down by the Hon Mr Justice Butcher… Read More

Boosting growth, competitiveness and productivity in the EU and UK

Low economic growth is a current challenge for most major European economies, especially given the new fiscal burden of increased defence spending. Funding social challenges—such as climate change, the digital transition and European security—requires either some parts of society to be worse off, or that economies generate new sources of… Read More