Fairness and competition in online markets: friends or foes?

Fairness is emerging as an increasingly important policy goal across sectors. We set out a framework for assessing fairness concerns, and examine the relationship between the aims of competition policy and fairness in current debates. Do the European Commission’s platform-to-business initiative and reputation systems for sharing platforms lead to fairer processes? And do online price differentiation and negotiations between platforms and content creators lead to fair outcomes? What is the role of competition in all of this?

Fairness has been gaining prominence in discussions of online markets, and has been considered in various high-profile decisions. For example, earlier this year the German competition authority, the Bundeskartellamt, found that Facebook’s data-gathering practices constituted an abuse of dominance due to Facebook’s unfair business terms.1 After a long and controversial debate, the European Parliament has accepted a copyright Directive that will ensure ‘a fair and balanced result that is fit for a digital Europe’, as promoted by Commissioner Andrus Ansip.2 This opens up the question of how competition and fairness relate to each other more generally.

Dimensions of fairness

Fairness has been at the forefront of recent debates among competition authorities and practitioners as well as among regulators. The first step in assessing its link with competition is to consider its various dimensions,3 of which two stand out.

- Process versus outcome. Looking primarily at process can mean that the focus is on the functioning of markets, irrespective of the outcomes achieved (which may or may not be equitable—among consumers as a group, for example). A focus on market outcomes could mean achieving equity in terms of the welfare derived from market transactions—across different consumers or producers, or between consumers and producers.4

- Vertical versus horizontal. Vertical fairness relates to the question of how to divide the economic ‘pie’ or total surplus among the economic agents in the value chain, including consumers.5 For instance, a price that exceeds and does not reflect the economic value of the product may not only be inefficient, but may also be considered excessive and unfair as it gives the (upstream) producers a larger share of the pie than would be observed in cost-related price-setting. Horizontal fairness focuses on processes or outcomes within a particular group—such as whether outcomes are fairly distributed across consumers, or whether platforms negotiate with all of their business partners in the same way.

Linking horizontal with vertical fairness, innovation may drive up returns for firms that invest in R&D, meaning that current prices appear to be higher than direct costs in order to reward the upstream firm for the risks and investments that it made in developing the new product. In this instance, consumers today pay for benefits that will also be enjoyed by consumers tomorrow, so there is an inter-temporal element to horizontal fairness.

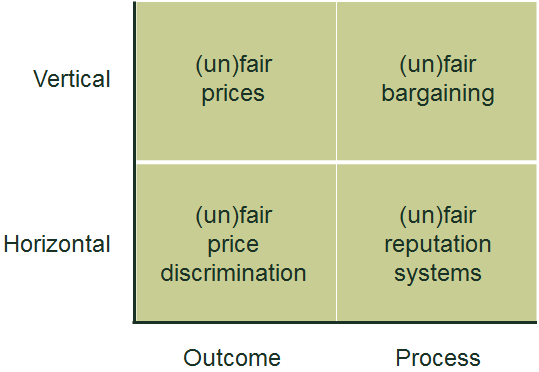

Figure 1 shows the kinds of concern raised by the current fairness debates in digital markets. We expand on these examples in the following sections.

Figure 1 Dimensions of economic fairness and issues

What does a fair process look like?

Firms and consumers in online markets often interact without communicating with each other in a physical space, often in fully automated ways, and without ever meeting. This means it is important for market participants to have trust in transparent market processes.

In this respect, there are two hot topics in policy formation: platform-to-business transactions, and reputation systems.

Transparency in platform-to-business transactions

Platforms are key players in online markets, with many businesses and consumers being matched through them. This has led the European Commission to express concerns about the bargaining power that large platforms have in transactions with their business users. These concerns have translated into proposals to increase the transparency and accountability of platform-to-business transactions.6

The proposed regulations are intended to stimulate self-regulation of ecommerce platforms in a wider sense, including marketplaces, online software application stores, social media platforms, search engines, price comparison websites, and ‘collaborative economy’ platforms.

The proposals stipulate transparency, in particular with regard to the platforms’ terms and conditions (T&Cs), including the main parameters for ranking. Platforms need not only to explain these parameters, but also to provide the reasons for the relative importance assigned to them. If T&Cs change, platforms need to explain factors that may play a role in an adjustment to their ranking, including the possibility to pay to influence positioning.

In effect, the regulations are likely to reduce the platforms’ bargaining power vis-à-vis their business users. More transparency on ranking mechanisms may give businesses the potential to have more influence over their ranking position, but may also open the door for gaming (by businesses) or copying of successful algorithms (by other platforms).

Trust through reputation systems

Another area that has grown substantially in the digital space is the ‘sharing economy’, where individual users offer services such as transport, accommodation or second-hand goods to other users. These transactions usually happen in unregulated spaces, which has created concerns that their quality may not be sufficient to meet minimum standards.7 This could lead to unfair treatment of consumers and/or established players, such as taxis and hotels, who face more intrusive regulation.

Reputation systems include the provision of comprehensive account information and the possibility for users to leave reviews after completed transactions. Such systems could increase transparency and promote fair transactions, as consumers can distinguish and obtain quality products in the absence of explicit regulation. In economics terms, reputation systems could facilitate matching between potentially heterogeneous buyers and sellers, and could help to reduce information asymmetry where buyers and sellers have not interacted before.

However, reputation systems may be flawed, and may allow for ‘unfair’ treatment through inaccurate reviews or biased behaviour based on the information provided. In particular, skewed incentives for writing reviews, and discrimination based on the personal characteristics of sellers or buyers, can undermine the fairness of interactions.

At the same time, the evidence suggests that reviews are generally positively biased.8 Platform design can improve incentives—for example, Airbnb reviews now become visible only once both sides have submitted their review (or after a period beyond which no more reviews can be submitted by either party).

Various platforms have also been shown to suffer from bias based on race or gender, leading to bias in reputations and transactions. For example, research shows that Lyft and Uber customers of Afro-American background wait longer for their cars, and female customers are taken for longer rides than their male peers.9 Gender bias also appears to be present on platforms for short-term labour, while peer-to-peer lenders have also taken into account physical appearance and ethnicity.10 Such bias may not only be illegal, but is also likely to be perceived as unfair, driving down the usage of certain platforms by negatively affected groups and driving up usage by those who are positively affected. Bias driven by personal information on a service provider can be reduced—for example, by removing information on gender or race.

The relationship between fairness and competition

In general, fair processes that promote trust and transparency are also favourable for competition because users (consumers and businesses) can compare competing offers and make decisions based on the relevant information.

In the context of the platform-to-business proposals, the effect on efficiency depends on the market and platform in question. The Commission’s proposals are likely to induce more businesses to use platforms (more),11 but a potential unintended consequence could be to reduce the number of platforms that are available to them. This is because the proposals are likely to raise compliance costs for platforms, and those that just break even in the absence of the regulations may find it unprofitable to stay in business when faced with increased transaction costs, potentially inducing them to leave the market. Removing bias from reputation systems is actually likely to increase competition as users receive more accurate and relevant information, thereby driving a positive impact on both fairness and efficiency.

What does a fair outcome look like?

As discussed below, new developments in online markets have stimulated debate about fair outcomes. This has already translated into ongoing investigations and policy debates for both horizontal and vertical relationships, especially concerning price differentiation and unfair pricing.

Differentiated prices

Algorithms and machine learning have become widely used tools for firms in digital markets. One of their many purposes is to change prices based on large amounts of information on the market environment and even individual consumers. Firms may determine prices based on the consumer’s willingness to pay or the cost of providing a service (which varies, for example, in insurance markets). This tends to be economically efficient if firms serve more consumers than they would with a single price.12

Price differentiation affects the distribution of surplus among consumers: if it reflects differences in willingness to pay, consumers who value a product more highly pay more for it than others, while still getting the same product. If price differences reflect different costs of serving consumers, setting different prices can remove cross-subsidies between different groups as prices become more closely aligned to the costs to serve each group. This may be considered unfair—for example, where poorer or more vulnerable customers are the higher-cost group to serve.

Whether differentiated prices are considered fair is likely to depend on the context. Some forms of differentiation are familiar and accepted, such as student discounts, different mobile tariffs, or yield management by airlines. If prices vary with willingness to pay, they appear to be more acceptable if a higher willingness to pay is driven by a factor such as higher disposable income than by factors such as consumer naivety or high switching costs. In the context of financial products, a removal of cross-subsidies is more likely to be deemed fair if consumers can influence their level of risk (e.g. through their vehicle driving behaviour).

Unfair prices

Consumers increasingly rely on platforms to access large amounts of digital content. This has generated concerns about ‘unfair’ compensation of content creators who produce news, reviews, music and audiovisual content.13 They might receive a small or no fee when users access their content in a digital form.

In March 2019, the European Parliament accepted proposals to update copyright legislation. Article 15 stipulates new rules for using editorial content, requiring platforms to compensate creators for using news snippets, for example.14

These proposals followed national initiatives (in particular in Germany and Spain) to strengthen publishers’ bargaining position by giving them ‘ancillary copyright’ and forcing intermediaries to obtain licences from publishers for snippets. These initiatives did not bring about notable changes in the market, because platforms suffered less from not dealing with specific publishers than the publishers did, leading to essentially free licences.15

For the outcome to be efficient, there should be a balance between production and dissemination: platforms should receive a share of the content’s value for users as a reward for dissemination, while producers should be incentivised to produce high-quality content. It is unclear whether the new provisions will lead to fairer outcomes, as no clear benchmark is available.

The relationship between fairness and competition

In terms of economic outcomes, tensions between fairness and competition may arise, depending on the precise meaning of fairness. In the context of personalised prices, there are cases in which differential pricing clearly increases economic efficiency, while the assessment of fairness depends on the notion of fairness applied. If fairness is understood to mean paying the same price as others for the same product, differential pricing will always be unfair. If, in contrast, fairness takes into account distribution among consumers of, for example, consumer surplus (i.e. the difference between willingness to pay and price) then differential pricing can make outcomes in these markets fairer.

Regarding the vertical distribution of gains between platforms and content creators, the copyright proposals do not elaborate on the type of fairness that these are intended to promote. This makes it difficult to assess the relationship between fairness and efficiency in this context. A more explicit definition of the fairness objective would be helpful to guide the policy discussion.

Conclusion: the relationship between fairness and competition

The overall aim of competition policy is to promote efficient markets by correcting for market failures or the anticompetitive behaviour of firms. Fairness is generally understood to be an objective in itself, although it may also improve society’s perception of markets more widely and thereby contribute to their efficiency.

However, fairness is a broader concept than the efficiency concept promoted by competition law and economics—in that firms can behave in ways that may be perceived as unfair without being in breach of competition law. This raises doubts about whether competition law is a suitable tool for making markets fair. Consumer policy and market regulation may be better suited to achieving fairness objectives.

There are many (potentially conflicting) concepts of fairness that vary across a number of dimensions, and authorities may apply more than one of these. As there is no single approach for capturing fairness in digital markets, concerns need to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. While a single definition of fairness may not be possible, firms and authorities will benefit from a consistent framework that narrows down what it means for markets to be ‘fair’.

1 Bundeskartellamt (2019), ‘Facebook, Exploitative business terms pursuant to Section 19(1) GWB for inadequate data processing’, 15 February. European Commission, ‘Google Search (Shopping)’, Case AT.39740. European Commission (2018), ‘Fairness in platform-to-business relations’. European Commission (2018), ‘Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services’, COM(2018)238/974102.

2 See European Commission (2019), ‘Digital Single Market: EU negotiators reach a breakthrough to modernise copyright rule’, press release, 13 February.

3 The Oxford English Dictionary defines fairness as ‘Impartial and just treatment or behaviour without favouritism or discrimination’. In this article, we refer to fairness in economic interactions and leave aside wider normative questions.

4 For more detail, see Oxera (2017), ‘To be fair: what does economic justice look like?’, Agenda, January.

5 Recent debate on fairness has also raised the question of how the producers’ share of the pie is split between employees (wages) and the owners (firm profits). For instance, see The Economist (2016), ‘Too much of a good thing’, 26 March.

6 European Commission (2018), ‘Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services’, 26 April, COM(2018)238/974102.

7 For example, see Chapter 4 of Federal Trade Commission (2016), ‘The “Sharing” Economy”: Issues Facing Platforms, Participants & Regulators’, an FTC staff report, November.

8 Resnick, P. and Zeckhauser, R. (2001), ‘Trust among strangers in Internet transactions: empirical analysis of eBay’s reputation system’, Advances in Applied Microeconomics, 11, pp. 127–57. Fradkin, A., Grewal, E., Holtz, D. and Pearson, M. (2015), ‘Bias and reciprocity in online reviews: evidence from field experiments on Airbnb’, The Sixteenth ACM Conference on Economics and Computation.

9 Ge, Y., Knittel, C.R., MacKenzie, D. and Zoepf, S. (2016), ‘Racial and gender discrimination in transportation network companies’, NBER Working Paper 22776, October. Browne, A.E. (2018), ‘Ridehail Revolution: Ridehail Travel and Equity in Los Angeles’, dissertation.

10 Hannák, A., Wagner, C., Garcia, D., Mislove, A., Strohmaier, M. and Wilson, C. (2017), ‘Bias in Online Freelance Marketplaces: Evidence from TaskRabbit and Fiverr’, The 20th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing (CSCW2017), February 2017, Portland, Oregon, USA. Ravina, E. (2012), ‘Love & Loans: The Effect of Beauty and Personal Characteristics in Credit Markets’, 22 November.

11 This is because the regulations give businesses more bargaining power when dealing with platforms, which could shift some of the joint surplus from platforms to these businesses.

12 For an overview, see Oxera (2015), ‘The Cloud, or a silver lining? Differentiated pricing in online markets’, Agenda, May. More detail is given in Bergemann, D., Brooks, B. and Morris, S. (2013), ‘The limits of price discrimination’, Cowles Foundation Discussion Paper No. 1896R, Yale University, 2 July; Dupuis, N., Ivaldi, M. and Pouyet, J. (2015), ‘A welfare assessment of revenue management systems’, Toulouse School of Economics working paper TSE‐547, 4 January; and Acquisti, A. and Varian, H.R. (2005), ‘Conditioning prices on purchase history’, Marketing Science, 24:3, pp. 367–81.

13 See the repeated reference to ‘fairness’, for example in European Commission (2016), ‘Promoting a fair, efficient and competitive European copyright-based economy in the Digital Single Market’, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, 14 September, COM(2016)592. A related concern is that the potentially low value of the digital income stream impedes the production of high-quality content; however, it is not clear how this relates to fairness concerns.

14 Hamilton, I.A. (2019), ‘Your memes are safe, but these are the other fiercely opposed changes Europe is making to the internet’, Business Insider, 26 March.

15 See also Oxera (2016), ‘An era of negotiation: news publishers and online intermediaries’, Agenda, October.

Download

Related

Access to land for mobile telecoms networks: a framework for negotiation and regulation

Mobile towers serve as the backbone of mobile telecoms networks, hosting radio access network equipment that enables us to receive calls, texts and to access the internet on our mobile devices. In turn, the ability of the builders of mobile towers to access land—whether that is on the ground,… Read More

What is venture capital, how does it work, and what are the risks?

In the third and final episode demystifying private equity, we explore the world of venture capital. While venture capital has delivered exceptional returns for some investors and founders, it’s also very high risk. So, is vibrant venture capital essential for economies seeking to boost innovation and drive productive growth? In… Read More