The Google case: shop till you drop (off the screen)

In 2017 the European Commission imposed a record €2.4bn fine on Google for abusing its dominant position in online search by giving preferential treatment to its own comparison shopping service. Such complex cases of leveraging of market power also arise in other digital markets, and raise several questions. How should competition authorities weigh benefits to consumers against harm to competition and competitors? How can competition concerns be remedied without affecting incentives to innovate?

Joanne wants to buy a pair of running shoes online. Google is her default search engine when she opens her browser. She types in ‘women’s running shoes’ and immediately gets a screen full of options, at the top of which are a series of colourful shoe images with blue links and prices. The information provided, including brand, retailer, price and user rating, help her make a decision quickly. She clicks on her preferred option and is taken to the retailer’s webpage, where she finalises the purchase.

Joanne is a happy customer: the process was smooth, she was given lots of choice, and she found the shoes she wanted. However, some of Google’s rivals feel differently, and so does the European Commission. While acknowledging that Google’s effective search engine brings many consumer benefits, the Commission is concerned that Google has used its strong position in search to exclude competing comparison shopping services.

The Commission’s decision to fine Google €2.4bn was made public in December 2017.1 The Commission found that Google engaged in two types of anticompetitive behaviour. First, it displayed the results of its own comparison shopping service, Google Shopping, prominently at the top of search results, in a dedicated space with enhanced features. Second, it demoted other comparison shopping services in the general search results, making its algorithm place them in lower-ranked positions.

Through Google Shopping, Google aggregates, sorts, displays and provides direct access to retailers’ webpages in exchange for a fee from the retailers. Other online platforms, including Nextag, PriceGrabber and Shopzilla, offer similar services, but they are not displayed by Google in the same way. This explains why Joanne (perhaps unknowingly) used Google Shopping instead of any other comparison shopping platform. When accessing Google, she was automatically attracted to the enhanced images of running shoes and the good positioning that the offers from Google Shopping enjoyed on Google’s results page.

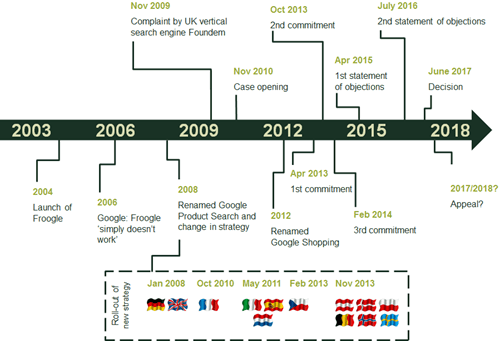

The Commission case had a long history, as shown in Figure 1. Froogle, Google’s first comparison shopping service, went live in 2004. It started as a stand-alone website with monetisation through additional advertisements. The ‘OneBox’ at the top of the search results was launched in 2008, alongside other changes to the search algorithm.2 This triggered a complaint by Foundem, a shopping comparison website, which led the Commission to open a formal investigation against Google in 2010.

Figure 1 Timeline of the Google investigation

The Google Shopping case raises many important questions. How to deal with leveraging of market power in digital markets? How to weigh benefits to consumers such as Joanne against the potential harm to competition? And how to find appropriate remedies for this type of behaviour? Competition authorities and courts around the world have taken various approaches.

Digital leveraging concerns

There seems little doubt that Google is currently the dominant search engine in many parts of the world. In most EU countries Google accounts for more than 90% of general online searches (with Bing and Yahoo! making up most of the remainder).3 Google entered this market relatively late, in 1998, but did so with a new and highly innovative search technology. Existing search engines such as Excite, AltaVista, Yahoo! and Lycos mainly ranked results by how many times the search terms appeared on a page, but had begun to struggle with helping users navigate through huge amounts of web content, a lot of it spam. Google’s method revolved around links between pages as a primary metric for page relevance, and significantly improved search functionality. By 2000, Google was the largest search engine in the world, and still is today. It made it into the top five global companies by market capitalisation, and ‘to google’ has become a widely used verb. This is a case study of successful innovation in a competitive market resulting in significant benefits to consumers and huge financial rewards and high market shares for the innovator.

But the success and high market shares have been accompanied by competition concerns, especially as Google has moved into other online activities on the back of its powerful position as a search engine—including online shopping, advertising, news, travel services and mapping. The Commission’s decision on Google Shopping reflects the debate on how competition authorities should handle leveraging practices in digital markets. This debate started in the 1990s with the Microsoft browser cases in the USA (when Microsoft integrated its Internet Explorer web browser into its dominant Windows PC operating system, at the expense of leading web browser, Netscape),4 and will no doubt continue. Indeed, the Commission opened a separate case against Google in 2015 for an alleged anticompetitive tying of the Android operating system with Google applications in mobile devices.5

A key precedent for leveraging practices in the EU is a 2004 case in which the Commission found that Microsoft had abused its dominant position in computer operating systems by tying Windows Media Player to its Windows operating system.6 The practice of pre-installing Windows Media Player left limited scope for effective competition in this market.

As a remedy, the Commission required that a version of Windows without Windows Media Player should be made available to PC manufacturers with no commercial disadvantages with respect to the bundled product.

In the meantime, digital markets have continued to see a trend towards more integrated services. Technology companies from different fields have merged in order to provide more personalised and wide-ranging services. For example, the acquisition of LinkedIn has given Microsoft the chance to provide new functionalities to both companies’ users, based on the networks and technologies that each developed separately.7 Facebook’s acquisition of WhatsApp and Instagram has allowed it to offer broader social interactions, which have recently been complemented by the launch of ‘Marketplace’, a dedicated space for local commercial interactions. Google includes travel and flight services as well as maps at the top of its search results.

The integration of services and leveraging of capabilities from different areas also allows innovation to take place. For example, starting later in 2018, Google Flights will use Google’s machine-learning algorithms to predict flight delays even before the airlines can do so themselves.8 It may be easier for larger players to add more services to their existing platforms, particularly if they have easy access to an established user base and important data sources.

While this may be good for innovation and technological progress, the question is open as to how far such practices harm competition for the provision of individual services, and ultimately harm consumers—thereby offsetting the innovation and convenience benefits that accrue to consumers who use an integrated service. In the Google Shopping case, the Commission gave considerable weight to the potential harm to competition in comparison shopping services.

Effects on competition and consumers

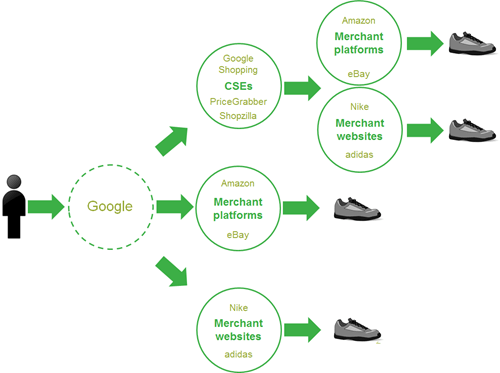

Let us go back to Joanne and her search for running shoes. She had alternatives to ‘googling’ for shoes: she could have gone directly to an online merchant, such as Nike, or to a merchant platform, such as Amazon. The vertical and horizontal relationships among comparison shopping, online merchants and merchant platforms are summarised in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Search and purchase options for running shoes

Source: Oxera.

The circumvention of Google may be more likely if, for example, Joanne does not want to go to the trouble of filling in payment details at the online merchants put forward by Google Shopping. She may prefer to take advantage of the fact that Amazon already has her information saved. Or maybe Joanne is searching on her mobile and likes the eBay mobile app, so buys a pair of shoes from there directly. The Commission considered, however, that these alternative channels did not provide a sufficient competitive constraint on Google.

The theory of harm that led the Commission to rule against Google was that, by giving a prominent position and enhanced visibility to Google Shopping and demoting its rivals, Google foreclosed the market to them, which in turn reduced choice for consumers. The increased prominence of Google Shopping implies that it has a dedicated space reserved at the top of Google’s results page. The demotion, on the other hand, implies that Google actively adjusts downwards the position of competing comparison shopping services. Indeed, the complaints from competitors arose when their online platforms could only be found on secondary results pages, reportedly as a consequence of a change in Google’s algorithm.

According to this reasoning, consumers are in an situation with a smaller variety of visible comparison shopping services—i.e. primarily Google Shopping—that may not offer them the best service. In the Commission’s view, this conclusion would hold even if the market definition were expanded to include merchant platforms.

Somewhat in contrast to the Commission, when the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) reviewed Google’s practices in 2013, it put more emphasis on efficiency benefits, driven by Google’s commercial rationale.9 The FTC acknowledged that competitors may have received less traffic as a consequence of Google’s product design, but considered this to be a by-product of a focus on enhancing the consumers’ experience:

While Google’s prominent display of its own vertical search results on its search results page had the effect in some cases of pushing other results ‘below the fold’, the evidence suggests that Google’s primary goal in introducing this content was to quickly answer, and better satisfy, its users’ search queries by providing directly relevant information. (p. 2)

The FTC further concluded that the demotion of rival comparison shopping services to secondary results pages allowed for a wider variety of results on the first page. For instance, the extra space on the first page implied that, in some cases, the retailer websites themselves would appear there, increasing the probability of consumers by-passing Google Shopping entirely. The FTC considered that this represented a potential improvement of the overall quality of Google’s search engine, and was therefore a reasonable justification for Google’s conduct. On this basis, Google was allowed to continue its conduct:

Challenging Google’s product design decisions in this case would require the Commission – or a court – to second-guess a firm’s product design decisions where plausible procompetitive justifications have been offered, and where those justifications are supported by ample evidence. (p. 3)

In a decision concerning Google’s alleged leveraging into mapping services in 2016, the UK High Court also placed considerable weight on consumer benefits.10 The case had been brought by Streetmap, a provider of online mapping services, which alleged that it had lost significant market share as a consequence of Google embedding its own mapping service into a dedicated OneBox.

The High Court dismissed the claim. The integration of Google Maps into Google was considered a technical improvement to the service in which Google had a dominant position—i.e. in the market of general search. In terms of Joanne and her running shoes, this innovation made it possible for her to immediately see maps when she ‘googled’ running events in her local area. The High Court further found that the effect of Google’s conduct on competition in the online mapping market was not ‘reasonably likely’ to have a serious or appreciable effect:

It is axiomatic, as I remarked earlier, that competition by a dominant company is to be encouraged. Where – as here – its conduct is pro-competitive on the market where it is dominant, it would to my mind be perverse to find that it contravenes competition law because it may have a non-appreciable effect on a related market where competition is not otherwise weakened. Accordingly, I consider that in the circumstances of the present case a de minimis threshold applies. For Google’s conduct at issue to constitute an abuse, it must be reasonably likely to have a serious or appreciable effect in the market for on-line maps. [emphasis original] (para. 98)

A key aspect of the High Court judgment in mapping is the principle that even dominant firms need to be allowed and encouraged to innovate. Whether, and to what extent, this implies that firms require some leeway to justify integrating products on the basis of dynamic efficiencies is subject to continued debate. Albeit in different cases, the US FTC and the UK High Court took somewhat different views from those of the Commission, illustrating that striking this balance is not an exact science.

What next? The ongoing debate over remedies

In its June 2017 decision, the Commission imposed a fine of €2.4bn. It did not impose a remedy, instead placing the burden on Google to propose a remedy that solved the Commission’s competition concerns within 90 days (on penalty of further fines).

From a public policy perspective, this is somewhat unsatisfactory after eight years of investigation. It means that there is still limited clarity over what is allowed and what is not allowed, and over how the right balance should be struck between consumer benefits and innovation on the one hand, and harm to competition and competitors on the other.

The outcome could have been very different. In 2014, when the investigation was still underway, Google and the Commission came close to agreeing a remedy whereby Google would present search results in such a way that competing offerings would appear as prominently as Google’s own.11

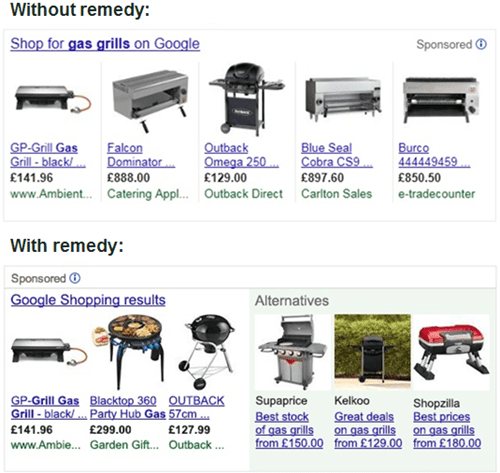

From a behavioural economics perspective, these commitments appeared to go a long way towards mitigating concerns about a lack of exposure for competing comparison shopping services. It would be made clear on the screen which were the Google Shopping results and which were the alternatives. Both sets would be presented in the same manner; if the Google results had photos or a picture then the alternatives would as well. In presenting the remedies, the Commission gave illustrations of a search for gas grills and one for cafés in Paris. The first of these is shown in Figure 3. The top picture shows the search results without the remedy. The most prominent listings are from five vendors of gas grills who have paid Google for the advertising. The bottom picture shows what would happen with the remedy. The first search results shown are now three options from Google Shopping (by vendors who paid Google directly), and right next to it, and equally salient, are three options from rival vertical search providers (SupaPrice.co.uk, Kelkoo and Shopzilla).

Figure 3 Display of Google ‘OneBox’ without and with the proposed remedy

However, the proposed remedies were ultimately rejected, as many parties still objected. The main concern was that Google would be able to extract vast rents from its competitors due to the auction mechanism underlying the allocation of OneBox space.12 In effect, competitors wanted access to this valuable advertising space at much lower rates, or even for free.

Similar concerns reportedly still exist with regard to the remedies that Google has proposed following the decision.13 Google Shopping now allows comparison shopping rivals to bid to appear in the OneBox space alongside merchant platforms. However, these rivals contend that this auction-based competition will remain ineffective as long as Google’s businesses are not structurally separated. It is therefore still far from clear where the ultimate balance will be struck.

Google has appealed the Commission’s decision on the Google Shopping case to the General Court.14 At the same time, EU policymakers have been considering options for regulating online intermediation platforms (including search engines) directly.15 All this means that the debate on the benefits and limitations to product integration on digital platforms is likely to continue for some time. Meanwhile, with or without remedies, Joanne and millions of other consumers will continue to use Google to shop online for running shoes, gas grills or anything else.

1 Press release: European Commission (2017), ‘Antitrust: Commission fines Google €2.42 billion for abusing dominance as search engine by giving illegal advantage to own comparison shopping service’, press release. Decision: European Commission (2017), ‘Commission Decision of 27.6.2017 relating to proceedings under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area’, Case AT.39740.

2 ‘OneBox’ is a dedicated space at the top of a Google results page that directly provides the information that Google considers most important to the user. For example, if the user typed ‘London weather’, Google would provide an illustrated weather forecast before any other search result. The OneBox for Google Product Search (as Froogle was renamed in 2008) provided images of the products that Google considered most relevant and, when clicked on, redirected the user to the stand-alone Google Product Search website.

3 European Commission (2017), ‘Commission Decision of 27.6.2017 relating to proceedings under Article 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and Article 54 of the Agreement on the European Economic Area’, Case AT.39740, table 2.

4 US v Microsoft, Civil Action No 98-1232 (TPJ), US District Court for the District of Colombia, Court’s Findings of Fact, 5 November 1999.

5 European Commission (2015), ‘Antitrust: Commission opens formal investigation against Google in relation to Android mobile operating system’, Fact Sheet, 15 April.

6 European Commission (2004), ‘Commission concludes on Microsoft investigation, imposes remedies and a fine’, press release, IP/04/382, 24 March.

7 Microsoft (2016), ‘Microsoft to acquire LinkedIn’, Microsoft News Center, 13 June.

8 Vanian, J. (2018), ‘Google Flights will now tell you about flight delays’, Fortune, 31 January.

9 Federal Trade Commission (2013), ‘Statement of the Federal Trade Commission Regarding Google’s Search Practices In the matter of Google Inc., FTC File Number 111-0163’, 3 January.

10 Streetmap.EU Limited v Google Inc. (2016) UK High Court of Justice, EWHC 253(Ch). Oxera acted as experts for Streetmap on this matter. Oxera has also advised Google on several matters (not the shopping case).

11 European Commission (2014), ‘Antitrust: Commission obtains from Google comparable display on specialised search rivals – Frequently asked questions’.

12 Duhigg, C. (2018), ‘The case against Google’, The New York Times Magazine, 20 February.

13 Titcomb, J. (2018), ‘Google still abusing search engine monopoly, rivals tell EU’, The Telegraph, 28 February.

14 European Commission (2017), ‘Action brought on 11 September 2017 — Google and Alphabet v Commission’, Case T-612/17), Official Journal of the European Union, 30 October.

15 Financial Times (2018), ‘Google targeted under EU plan to regulate search engines’, 14 March.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More