Margins of error? Prices vs margins in cartel overcharge estimation

In follow-on claims for cartel damages, a key step is to estimate the cartel overcharge—the amount by which the cartel raised prices to purchasers. Margins analysis and price analysis are two widely used approaches for estimating overcharge. What are their strengths and weaknesses, and is one more appropriate than the other?

Effective cartels can affect competition and market outcomes in a variety of ways. They can lead to higher prices and lower quantities, or reduce the incentives to cut costs and to innovate.

Estimating the cartel overcharge often involves evaluating and comparing the prices paid by the purchaser, or the margins earned by the cartelist, with those that would have been paid, or earned, without the cartel. Numerous methods have been applied to estimate the overcharge, and the suitability of each depends on the economic context and data availability, and the specifics of each case. The most commonly used methods—‘comparator-based’ approaches—use data that is not affected by the cartel behaviour to estimate the level of the overcharge.

Oxera has advised several claimants and defendants in follow-on claims in recent years. Drawing on lessons from these cases, this article discusses two key approaches—margins analysis and price analysis—and looks at where each one may be more appropriate.

Estimating the overcharge

An estimate of a cartel overcharge should take into account the full increase in the prices paid by the relevant party as a result of the cartel only, separating out the effects of other factors. Indeed, when cartels are not effective, price movements will still be being driven by other factors, such as cost and demand changes.

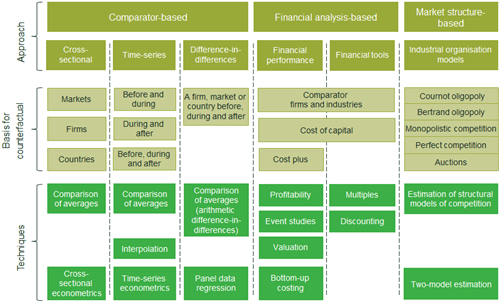

There are three broad groups of methods and models for estimating the cartel overcharge: comparator-based, financial analysis-based, and market structure-based, as shown in Figure 1. The classification has three levels: the approach, the basis for the counterfactual, and the estimation techniques that can be used.

Figure 1 Classification of methods and models

Comparator-based models seek to compare prices paid by customers, or margins earned by the sellers, during the cartel period with those that would have been paid or earned without the infringement (the ‘but for’ scenario). The but-for prices or margins are hypothetical values that cannot be directly observed and therefore need to be estimated. This is often done using econometrics with data from a period or market that is not affected by the defendants’ behaviour. Comparator-based analysis is typically undertaken using one of two approaches:

- margins (or price–cost) analysis—comparison of during-cartel margins with other relevant margins, either as a simple comparison or using an econometric approach. A price–cost econometric approach that does not restrict the relationship between prices and product-specific costs can also be used;[1]

- price analysis—comparison of the during-cartel prices with other relevant prices, using proxies for costs that are independent of the cartel (such as product characteristics). This approach is robust to cost-measurement issues and any cartel effect on costs.

The main difference between the two is that margins analysis controls for the product-specific costs reported by the defendants, while price analysis instead uses cost proxies that are considered to be independent of the cartel.

An economic expert may rely on a number of approaches, and use either analysis to conclude on the level of overcharge. Although different methods are often complementary, they may still lead to different estimates in practice. These differences may arise due to differences in the data, methodological issues, or both. The potential reasons for the difference in estimates should be taken into account when deciding which approach to favour.

Margins analysis: advantages

Margins analysis estimates the level of the overcharge by taking into account the reported costs incurred by the defendants in relation to the production and/or distribution of the cartelised good. In essence, this method assumes that the effect of the cartel agreement is fully reflected in the profit of the defendant.

If high-quality and comparable information is available on margins (i.e. prices, revenues and costs) both during and after the cartel period (or from a comparable market unaffected by the cartel), margins analysis can be expected to produce a reasonable estimate of the cartel overcharge, assuming that the cartel did not affect costs. In this context, margins analysis has a number of advantages over other approaches, as follows.

- It can help to control for variations in the relevant cartelised products by using the costs of the product, as reported by the defendants. This can be useful where the products are bespoke or change over time (although if the products are too bespoke, the cost data may be complex and incomparable, as discussed below).

- Reported costs incurred by the defendant are taken into account directly, so it is not necessary to proxy for the change in these costs, for example with inflation.

- The results are easy to present and understand.

However, acquiring high-quality, comparable information is not always feasible, particularly for costs. Data that might be readily available, such as accounting information, is often not granular enough and may not reflect the relevant economic costs. Furthermore, if the cartel affected costs directly or at the level of innovation, margins analysis may underestimate the overcharge.[2]

Margins analysis: disadvantages

The disadvantages of margins analysis fall into two main areas:

- the assumption that the effect of the cartel is fully reflected in the profit measure;

- measurement issues.

Cartel effect on costs

Although the aim of many cartels is to raise profits by charging higher prices, costs may also be higher than in the competitive outcome.[3] For example:

- if the cartel raises prices, this could reduce financial pressure on firms to lower their costs, which in turn could be associated with slack in the form of lower productivity. This could occur if there is a separation between ownership and control of the firms, where managers may have objectives other than simply maximising profits. The lack of competition makes such inefficiencies possible, and this effect is known in the economic literature as ‘X inefficiency’;[4]

- by shifting the incentive structure for firms in the market, the members of a cartel may innovate less than they would ‘but for’ the cartel. This is due to the reduced rivalry between firms, which can slow the rate of development.[5]

If the cartel has affected costs in these ways, margins analysis will produce a biased estimate of the overcharge. If actual costs are higher as a result of the cartel, all else being equal, margins analysis will underestimate the level of the overcharge.

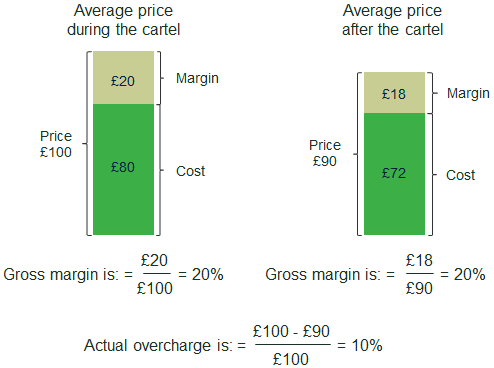

The stylised illustration in Figure 2 shows a case where the cartel affected reported costs while maintaining a constant percentage margin. The overcharge might appear to be equal to 0% according to margins analysis, while the actual overcharge, based on the prices the customer paid, is 10%.[6]

Figure 2 A case where a cartel effect on costs reduces the overcharge estimate

Source: Oxera.

The extent to which a cartel has affected costs can be tested empirically if appropriate data is available.

Quality of cost information available

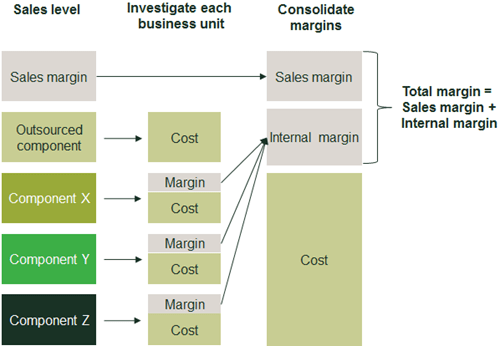

As noted, margins analysis requires high-quality, comparable information on costs over time. Many companies are made up of several business units, potentially in different countries, with each contributing different components to the final product. Internal transfers (purchases) among these business units mean that a margin for one entity is a cost for another. In such cases, forming consolidated margins, which are required for an accurate overcharge analysis, can be a data-intensive and complex task.

Figure 3 shows a stylised example of margin consolidation.[7] At the sales level, the total price is calculated by adding the heights of the individual bars. However, each of the costs associated with an internal transfer contains a margin, which is available from the financial information of the relevant business unit. The overall consolidated project margin is then formed by summing all the individual margins.

Figure 3 Consolidated margins: stylised example project

While the overall principle is simple, in practice there may be a number of issues, such as the following.

- The definition of a gross margin may vary between, or even within, the defendants (i.e. across business units).[8] In particular, the treatment of indirect costs may vary, which may affect the classification of costs, and can lead to a sample containing margins that are not comparable.

- Even for a given business unit of a single defendant, the treatment of indirect costs may vary over time as accounting practices change.

- Some of the key information required to construct consolidated gross margins may be missing or inaccurately recorded:

- if a significant amount of the required margin information is missing during the cartel period, margins analysis could lead to an underestimate of the cartel overcharge;[9]

- if there is a systematic pattern in the missing information during the cartel period (e.g. for the first five years of the infringement), the cartel sample period will not be representative.

- Reported accounting costs may not be representative of the actual economic costs of interest.[10] The economic cost of the cartelised product should include all variable and avoidable costs in relation to the production and/or distribution of the units bought by the claimant.

If many of these, or related, data issues are present, and it is believed that the cartel may have increased costs, margins analysis could lead to a biased estimate of the cartel overcharge, and an alternative method may be more appropriate.

Price analysis—the solution?

Many of the potential problems with margins analysis described above relate to cost information. Price analysis, on the other hand, avoids the need to obtain reported cost information from the defendants by using suitable proxies (such as a labour cost index). As such information is more readily available, price analysis has the following advantages:

- it has lower data requirements, and is therefore likely to cover a more representative sample of the cartel period. This is important if the effectiveness of the cartel varies over time;

- by using proxies for costs that are independent of the cartel, this analysis is unaffected by most of the potential biases of margins analysis;

- the price information and cost proxies are often easily observed and known to claimants and defendants;

- it is not subject to the cost definition issues of margins analysis.

However, other issues often need to be considered when relying on price analysis—in particular, the effect of changes in production costs (i.e. cost inflation). Many cartels span a decade or more, so accounting for this is usually important. In particular, if cost inflation is not properly accounted for, the estimate of the cartel overcharge may be obscured. This is because the overcharge increases the prices in the earlier (cartelised) period relative to the after-cartel prices, whereas cost inflation generally works in the opposite direction, resulting in increased prices in the later (competitive) period relative to the earlier (cartelised) period. Given that the effects of the overcharge and cost inflation work in opposite directions, they may cancel each other out. If this is the case, a simple comparison of the actual prices paid in both periods could be misinterpreted as showing evidence of an ineffective cartel with zero or even negative overcharge.

Cost indices can be used to proxy the inflation of input prices over time. As cost inflation is an important aspect, the choice of cost index is important in estimating a robust overcharge, as different indices lead to different overcharge estimates. A bespoke cost index can ensure that the general inflation of the specific input costs relevant to the cartelised product is captured, rather than general economy-wide inflation. However, even bespoke indices may not be able to capture all the cost inflation factors and specificities of the relevant products. This is why margins analysis, using the defendants’ product-specific reported costs, is appealing.

Beyond cost inflation, there is also the question of which other product characteristics, such as technical specifications, should be taken into account, and how good these characteristics are at predicting costs. However, technical characteristics alone may not be able to accurately capture all the differences in costs across products, particularly for highly bespoke products. In such cases it is important to ensure that the products included in the analysis are comparable, and that any unusual types are adequately controlled for or excluded.

Conclusion

Margins analysis has a number of advantages: it controls for product heterogeneity, does not require the use of a proxy (such as an inflation index) to control for changes in production cost, and may be more readily understood by judges and business executives than other methods. However, it can be less reliable under certain circumstances, for example if the product is complex and produced by firms with complicated internal structures, or if there is evidence that the cartel may have affected costs.

In such cases, price analysis may be a better solution as it is robust to problems associated with reported cost information, including a potential cartel effect on costs. However, it can have its own disadvantages, particularly in terms of how to control for inflation and whether the cost proxies can adequately control for product heterogeneity and changes in production costs over time.

In cartel overcharge estimations, it is therefore necessary to weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of each type of analysis undertaken, and consider why their estimates may vary.

[1] The terms ‘margins’ and ‘price–cost’ analysis are used interchangeably in this article, as the relevant feature, the reported cost variable, is common to both approaches. The distinction is that price–cost analysis does not restrict the relationship between prices and costs. Technically, a margins analysis has prices and costs on the left-hand side of the equation as the dependent variable, while a price–cost analysis has prices on the left-hand side as the dependent variable and costs as a control on the right-hand side. This article focuses on percentage margins rather than cash margins, although both forms rely on reported costs.

[2] This assumes that the cartel increases costs relative to the but-for scenario (for example, limited competition may mean less pressure on reducing costs).

[3] For example, see chapters 2.3 and 2.4 of Motta, M. (2004), Competition Policy: Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press. See also Günster, A., Carree, M. and van Dijk, M.A. (2012), ‘Do cartels undermine economic efficiency?’, American Economic Association 2012 Annual Meeting, 8 January.

[4] Leibenstein, H. (1966), ‘Allocative efficiency vs. “X-efficiency”’, The American Economic Review, 56:3, pp. 392–415.

[5] The relationship between the competitive structure of the industry and the level of innovation has been debated in the economics literature since Schumpeter, J. (1942), Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, Harper & Brothers; and Arrow, K. (1962), ‘Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources to Invention’, in Universities-National Bureau Committee for Economic Research and the Committee on Economic Growth of the Social Science Research Councils (ed.), The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity: Economic and Social Factors, Princeton University Press, pp. 467–92. Although there is no clear consensus on the issue, one major contribution concludes that innovation shows an inverted-U relationship with the level of competition: see Aghion, P., Bloom, N., Blundell, R., Griffith, R. and Howitt, P. (2005), ‘Competition and Innovation: An Inverted-U Relationship’, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120:2, pp. 701–28.

[6] Defined as the increase in price paid as a result of the cartel, as a proportion of the price paid.

[7] In practice, the relationship between business units may be more complex—for example, there could be several layers of purchases and transfers between business units.

[8] For example, if the defendants are global firms, accounting practices may vary across countries.

[9] Where margins information is missing, the margin is implicitly treated as a cost. If a significant amount of margins information is missing during the cartel, this therefore lowers the during-cartel margins, biasing the overcharge estimate downwards.

[10] See, for example, Davis, P. and Garces, E. (2009), Quantitative Techniques for Competition and Antitrust Analysis, Princeton University Press, p. 125.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More