Move fast and analyse things: sensible regulation for digital markets

Fast-moving digital markets require equally nimble regulatory authorities to oversee them. However, speed of action must not come at the cost of robust market analyses, unless we are to risk jeopardising the benefits digital markets have to offer. In this article—the first of a new series—we set the scene as governments around the world grapple with how to regulate digital business models. Throughout the series, we will tackle many of the questions regulators must answer if they are to rise to this challenge, asking what can be learned from decades of regulation in other markets.

As the presence of new and disruptive digital services has expanded within the economy, there are growing concerns that the traditional tools of antitrust and consumer protection are ill-equipped to deal with them in a timely fashion. Digital markets are frequently characterised by strong network effects, economies of scale and scope, data advantages and/or ecosystem effects. This can mean that by the time an ex post antitrust case concludes—which can take half a decade or more—the ‘horse has bolted’ and the market has tipped to a ‘winner takes most’ equilibrium.

Indeed, a frequent complaint of those competing in digital markets has concerned the (lack of) speed of traditional ex post competition tools when it comes to assessing and adjudicating on new forms of behaviour. This is unsatisfactory all round: for consumers, who may miss out on the benefits of more vigorous competition in the form of new services; for competitors, who may be denied market opportunities; and for the firms subject to investigation, who face years of uncertainty as a result of lengthy legal proceedings.

On a more fundamental level, the objective of ex post competition law (specifically, Article 102 TFEU and its national equivalents) is not to eliminate or reduce dominant positions, but rather to prevent the abuse of dominance. As such, there are inherent limitations to what this tool can be expected to achieve on its own. This has led to growing calls from authorities and policymakers around the world for new ex ante tools and powers that they can use to pursue different objectives, such as actively intervening in markets to prevent or erode dominant positions; as well as promoting fairer and more competitive market outcomes. While this may be beneficial in some cases—and even necessary where enforcement gaps have opened up—care must be taken to properly understand the wider implications of these new provisions before acting.

In this article—the first of a new series—we set the scene for the journey ahead and ask what lessons we can learn from existing regulation in other sectors as policymakers around the world begin to debate new legislative proposals. Principal among those is the European Commission’s Digital Services Act package, unveiled on 15 December 2020.1 The package comprises both the Digital Services Act (DSA), focused on the responsibilities and liabilities of all digital service providers, and the Digital Market Act (DMA), targeting issues of unfairness and lack of contestability in digital markets. At the same time, the UK Government is taking the first steps toward creating a new digital regulator in the form of a Digital Markets Unit (DMU) within the Consumer and Markets Authority (CMA), following the publication of the CMA’s Digital Markets Taskforce recommendations on 8 December 2020;2 while on 14 January 2021, the German Parliament passed the proposed “Competition Law 4.0” amendments to impose new competition regulations on digital platforms.3

Despite this progress by policymakers, many fundamental questions remain unanswered. To date, much of the economic research into digital markets has centred on the traditional issues of competition policy (i.e. market power, barriers to entry, and exploitative and exclusionary conduct) and the trade-off that may exist between ex ante and ex post intervention to tackle these. However, the policy debate extends well beyond this relatively familiar territory, encompassing issues as diverse as data privacy, online intermediary liability, fairness, online harms and media plurality. Future articles in this series will examine a selection of these issues in more detail, addressing questions such as the following.

- If data access is going to be mandated, how can you value the data a business holds, and set fair charges for access to it?

- How can dynamic competition be accounted for and further fostered by the regulatory proposals?

- Are the traditional tools of profitability analysis effective in assessing competition between digital businesses?

- Is there a tension between privacy and competition and/or between fairness and competition?

- What can we learn from the regulatory approach in other sectors?

Answering these—and many other—detailed questions will be imperative to ensure that any new regulatory provisions are robust, effective, and forward-looking.

Where are the market failures?

Given the wide range of digital services now on offer, it is unsurprising that an equally wide range of issues have emerged for policymakers to contend with. However, the key to designing sensible regulation is to first identify and categorise those problems that cannot be resolved—or that are exacerbated by—free market dynamics. In economics, we refer to these problems as market failures. Once these are identified, clear regulatory objectives can be determined that will guide the analysis and determine the suitability of different remedy options.

To aid our understanding of the potential market failures that may warrant regulation in digital markets, the various concerns that have been raised in different studies (most notably, the EU’s Special Advisers Report,4 the UK’s Furman Review,5 and the Chicago School’s Stigler Center Report)6 can be grouped into four broad pillars:

- competition dynamics and market power: this covers a wide range of issues arising from the existence of strong network effects and scale economies, which can result in ‘gatekeeper’ positions by large digital platforms. Proposed remedies include changes to (or even the reversal of) the burden of proof in antitrust and merger control, as well as the creation of dedicated regulators to impose ex ante remedies that will promote entry and competition and prevent any potential abuse of market power;

- data protection and privacy: an important enabler of many digital business models is the insight gleaned from collecting large amounts of user data (including from both private individuals and businesses). This data can provide a detailed understanding of consumers’ behaviours and preferences, enabling the improvement and customisation of products and services; and it is also highly valued by advertisers and other businesses. However, questions have arisen as to whether consumers are free to exercise meaningful choice over how their private data is used, as well as whether their privacy is adequately protected. Legislation such as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the proposed Data Governance Act,7 and the forthcoming e-Privacy Regulation8 will continue to shape the market in this regard;

- liabilities and safe harbours: ‘Move fast and break things’ was Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s famous motto for his fledgling company, neatly encapsulating an era in which Internet intermediaries were shielded from liability for any third-party content they carry—a provision granted by the eCommerce Directive in the EU and Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act. However, the debate has grown around the appropriate balance of responsibilities between digital service providers and their users, as well as the wider impact these services are having on societal concerns such as democracy, freedom of speech and online harms. While the DSA starts to address these in the context of internet intermediaries, the Commission is set to publish further proposals in 2021 around the liability attached to the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI). These follow from the principles for trustworthy AI outlined in the Commission’s AI White Paper, published in February 2020;

- fairness: as the importance of some large online platforms in the economy has grown, concerns have arisen that their bargaining power may allow them to impose unfair commercial conditions on businesses that have become economically reliant upon them, without necessarily falling foul of competition rules. This was indeed one of the prime motivations behind Europe’s Platform-to-Business (P2B) Regulation.9 In addition, concerns have been expressed about the fairness of certain market outcomes and practices, such as the distribution of value between platforms and content creators; the ranking and prominence given to different businesses by algorithms; and the use of data to personalise pricing, offers and advertising to consumers.

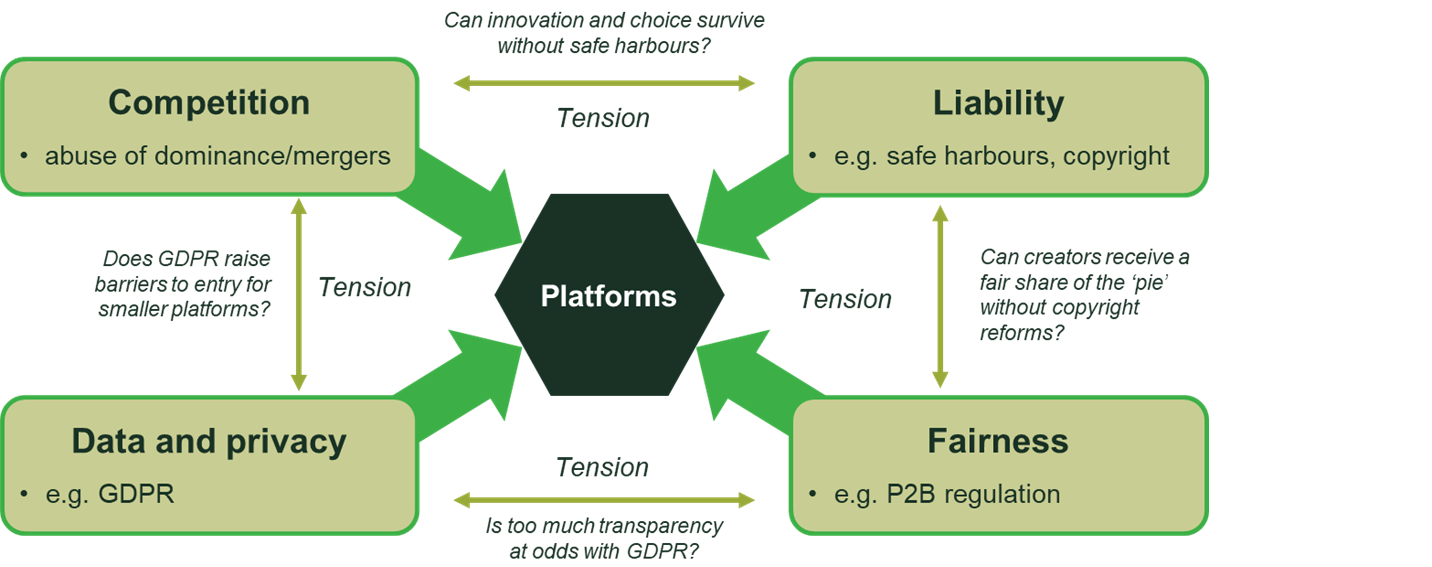

As the debate around digital regulation unfolds, the tensions that exist within and between these different objectives are coming to the fore (see Figure 1). We expand on several of these key tensions below.

Figure 1 Tensions between different aspects of digital regulation

Static versus dynamic competition

In general terms, competition policy has developed a keen focus on the static contestability of markets—a perspective that has permeated the debate around digital regulation. However, in these rapidly changing markets, this raises the question of whether too little attention is being paid to dynamic competition and the critical role innovation plays as a driver of consumer welfare.

Dynamic competition relies on two important market features:

- that markets are contestable—that is to say, firms with new ideas or innovative solutions can compete fairly for customers in the market;

- that the gains from innovation are sufficiently appropriable—meaning innovators can capture a fair share of the value generated by their innovation, so as to justify their risky investment of time and capital.

While the contestability concept appears frequently in regulatory discourse, there is much less focus on appropriability. For example, the Impact Assessment accompanying the DMA mentions contestability more than 100 times, but makes no direct mention of appropriability.10 Crucially, measures designed to increase the contestability of markets are also likely to reduce the perceived appropriability of value by potential innovators. This creates an acute policy trade-off requiring greater focus and further detailed analysis, to ensure an optimal balance that fosters innovation and strengthens dynamic competition.11

Privacy and competition

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) was heralded by many around the world as a pioneering piece of legislation enhancing consumers’ protection of and control over their personal data. However, concerns have been raised that it may also be having the unintended consequence of raising barriers to entry for smaller firms, which could increase concentration and market power in some digital markets.

Indeed, both Apple12 and Google13 have come under scrutiny for practices that restrict the use of cookies to track users across sites, with the CMA having opened an investigation into Google’s ‘Privacy Sandbox’ project in December 2020.14 While these practices likely enhance the privacy of data subjects, a by-product is that it may become harder for some third-party digital service providers to compete effectively.

For example, the tracking of users around the web is integral to many key activities in the online advertising value chain, including audience targeting, measuring campaign reach, and calculating conversion metrics. However, in the absence of key browser features—particularly third-party cookies—effective tracking will become considerably harder for those smaller publishers with a limited number of online sites.

In contrast, large digital ecosystems that can combine data from prime consumer-facing websites, as well as gateway interfaces such as apps and browsers, may be found to have an increasingly advantageous position when it comes to effective ad-targeting. The CMA has committed to work closely with the UK Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) as it examines Google’s Privacy Sandbox, to ensure that the design of new measures do not protect privacy at the cost of competition, or vice versa.

Liability versus contestability

A similar tension arises when it comes to the liability borne by digital services for any third-party content they carry. Many digital business models operate as multi-sided platforms, creating value by bringing different user groups together. For example, an online marketplace facilitates trade between buyers and sellers of goods and services; while online video sharing websites connect content creators, viewers and advertisers, creating value for all parties.

This raises the question of who should be liable if defective or illegal products, substandard services, or illegal content are shared across a platform. Currently, platform operators enjoy a broad limitation on their liability for any such problematic goods and services. This acts as an important enabler of innovative start-ups—which might otherwise face an unmanageable level of legal risk—promoting their growth and contestability in the market.

However, a debate is unfolding as to the appropriate balance of responsibility between platforms and society, particularly as the impact of inappropriate content spills over into broader societal concerns such as freedom of speech and the integrity of democracy. Within the EU, the Commission’s DSA proposals maintain a limitation on platforms’ liability for third-party content, but introduce new procedural obligations that platforms must follow to protect consumers and promote trust in online services. Importantly these provisions must remain clear and proportionate if they are to avoid disadvantaging smaller platforms as they compete with deeper-pocketed competitors.15

Efficiency versus fairness

The central role online platforms play in the global economy is, in part, due to the economic efficiencies this type of business model can unlock. For example, by helping realise scale and scope economies for their users, online platforms can increase trade and reduce costs. Similarly, ad-targeting can help consumers discover products and services they would not otherwise have found; while product and price personalisation can enable businesses to reach a broader range of customers, expanding the market and maximising total welfare.

However, the key characteristics of digital services that give rise to these efficiencies can also be a cause for concern. For example, the wide reach of online platforms—in terms of geography and user base—is an important benefit for business users. At the same time, there are concerns that some online platforms may become so strong that they can impose unfair terms on users. This could mean gathering and combining consumers’ personal data by default, or imposing strict terms of access on business users.

Building on the existing provisions laid down in the Platform-to-Business (P2B) Regulation, the Commission’s DMA proposals include several provisions that appear to target perceived issues of fairness. For example, Article 5(a) prohibits gatekeepers from combining personal data from different services without explicit user consent; while Article 6.1(k) ensures fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) access to gatekeepers’ app stores for all software vendors. This only scratches the surface, with many other provisions for free or FRAND access to data and gatekeeper services being included in the DMA.

Importantly, when assessing these provisions it must be recognised that many practices that appear unfair to one party (e.g. restricting access) can be critical to the proper functioning of the platform ecosystem as a whole (e.g. ensuring quality and security, or continued investment in the service provision). In general terms, provisions that focus on fairness in process are more likely to lead to a good overall balance; while provisions that have a set outcome in mind (i.e. a predetermined view of what fair should look like) are more likely to risk unintended consequences that reduce efficiency and value overall.16

The road ahead

While it is tempting to think of ‘digital’ as a single sector or market (particularly that of online platforms), in reality this is not the case. There are a wide variety of different digital services, operating in varied market environments and employing a range of different business models. The result is that ‘digital markets’ in fact comprise a large number of unique permutations of business model, market environment and competitive forces, each creating a particular set of incentives for businesses and producing different issues for regulators.

The scope of these fast-moving businesses to create significant gains for consumers in a short period of time is not in doubt, but nor is the speed at which any existing market failures can be amplified. At the same time, however, inappropriate regulation could give rise to considerable harm. It is therefore imperative that regulators and practitioners alike continue to study and understand the different market dynamics in digital activities as diverse as: eCommerce, mobile operating systems, cloud computing, online storage, photo sharing, online searching, online advertising, music streaming, video services, smart assistants, navigation services and smart home devices. Indeed, interventions that might be beneficial in one context may be inappropriate—or even harmful—in another.

Many questions remain unanswered that will no doubt keep us all on our toes seeking answers for many years to come. In future articles of this series, we will aim to provide some answers to these questions while, almost inevitably as our understanding of the issues expands, posing new ones.

1 European Commission, ‘The Digital Services Act package’.

2 CMA (2020), ‘A new pro-competition regime for digital markets: Advice of the Digital Markets Taskforce’, December.

3 See: https://www.bundestag.de/dokumente/textarchiv/2021/kw02-de-digitalisierungsgesetz-gwb-814250.

4 European Commission (2019), ‘Competition policy for the digital era: Final report’.

5 HM Treasury (2019), ‘Unlocking digital competition: Report of the Digital Competition Expert Panel’, March.

6 Stigler Center (2019), ‘Stigler Committee on Digital Platforms: Final Report’, September.

7 EU COM/2020/767 final ‘Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on European data governance (Data Governance Act)’.

8 See: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-a-europe-fit-for-the-digital-age/file-jd-e-privacy-reform.

9 EU Regulation 2019/1150 on promoting fairness and transparency for business users of online intermediation services.

10 Oxera analysis of European Commission (2020), ‘Commission Staff Working Document: Impact Assessment report accompanying the document Proposal for a regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on contestable and fair markets in the digital sector (Digital Markets Act)’, 15 December.

11 For more detail on this topic see Oxera (2020), ‘The impact of the Digital Markets Act on innovation: Helping or hindering innovation and growth in the EU?’, report Commissioned by Amazon, November, section 5.

12 See Barker, A., McGee, P. and Abboud, L. (2020), Financial Times, ‘Apple hit with antitrust complaint in France over privacy controls’, 28 October.

13 Lomas, N. (2020), ‘Digital marketing firms file UK competition complaint against Google’s Privacy Sandbox’, TechCrunch, 23 November.

14 Gov.uk, ‘CMA to investigate Google’s “Privacy Sandbox” browser changes’, 8 January.

15 For more detail on this topic, see Oxera (2020), ‘The impact of the Digital Services Act on business users’, 20 October.

16 For more discussion on the different aspects of fairness, see Oxera (2019), ‘Fairness and competition in online markets: friends or foes?’, Agenda in focus, April; and Oxera (2020), ‘Platforms at the gate? Initial reactions to the Commission’s digital consultations’, Agenda in focus, June, section 4.

Download

Related

Leveraged buyouts: a smart strategy or a risky gamble?

The second episode in the Top of the Agenda series on private equity demystifies leveraged buyouts (LBOs); a widely used yet controversial private equity strategy. While LBOs can offer the potential for substantial returns by using debt to finance acquisitions, they also come with significant risks such as excessive debt… Read More

Company valuation in post-M&A disputes—the Mahtani v Atlas Mara ruling

Post-merger and acquisition (‘post-M&A’) disputes can take many different forms, such as breach of representations and warranties, fraud and misrepresentation claims, and post-completion breach of contractual obligations. This article discusses the valuation issues in a post-completion breach case based on the ruling handed down by the Hon Mr Justice Butcher… Read More