Private retreat: are we witnessing the decline of public equity markets?

Public equity markets bring substantial benefits. However, in recent years there has been a fall in the number of initial public offerings (IPOs), and an increase in delistings as companies seek to remain or become private. What is driving this decline in listings? Should policymakers be concerned?

This article is based on Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November, prepared for the European Commission.

While stock markets were first developed in Europe, European public equity markets have since fallen behind in global terms. While Europe’s economy is of a similar size to that of the USA, its public equity markets are much smaller—and they are smaller than Asia’s markets when measured by market capitalisation relative to gross domestic product (GDP).1

Public equity markets provide an effective way to share risk and allocate capital efficiently between savers and borrowers. A steady flow of companies onto the market, via IPOs, is essential to this process. IPOs enable firms to raise funds and their profile as they scale up and grow. Early-stage investors can use IPOs as an exit route. Well-functioning public markets also exert market discipline on firm valuations and organisational behaviour.

However, our analysis for the European Commission shows that between 2010 and 2018 the total number of listed companies in the EU-28 declined by 12%—from 7,392 to 6,538—while GDP grew by 24% over the same period. Although there was an increase in listings in some small financial centres (such as Stockholm and Warsaw), the larger financial centres (such as Frankfurt, Paris and London) all experienced declines.

So what’s going on? Why are we witnessing the decline of public equity markets in the larger financial centres?

Long-term trends

The decline in the number of listed companies is not a recent phenomenon in some geographies. In a 1989 Harvard Business Review article, Professor Michael Jensen from Harvard Business School predicted ‘the eclipse of the public corporation’, arguing that the publicly held corporation had outlived its usefulness in many sectors.2

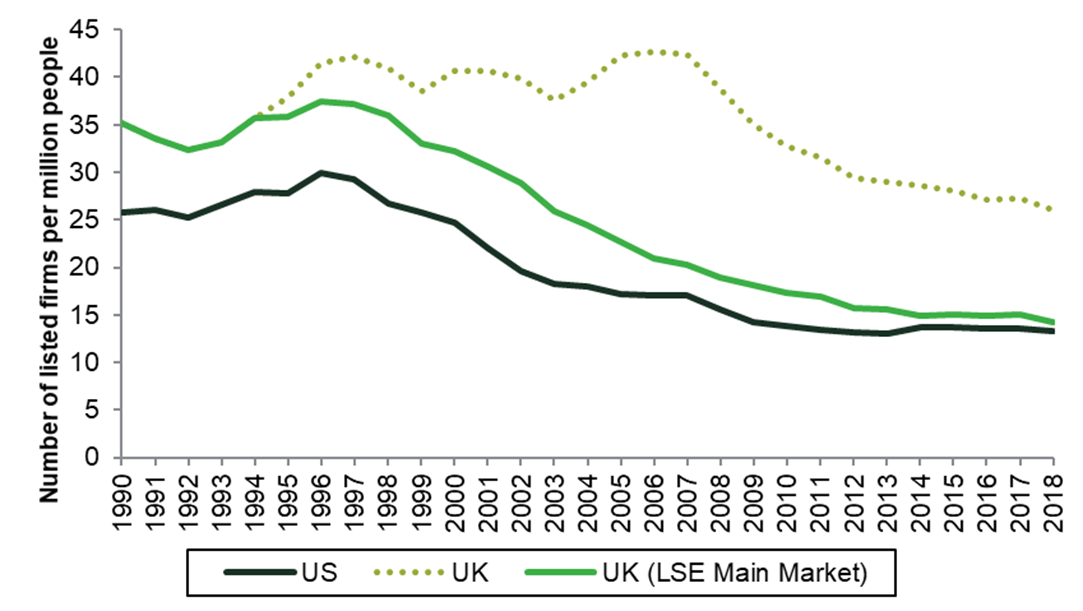

Figure 1 highlights how the number of listed companies per capita has declined significantly in the USA and UK.

Figure 1 Number of domestic listed companies

Source: Oxera analysis of data from stock exchange factbooks and the World Bank.

In the USA, there has been a continual decline in the number of public companies since 1996, leading some academics to estimate that the ‘listing gap’ (defined as the difference between the actual number of listed firms and the number that could be listed) in the USA was around 5,000 companies in 2012.3

As shown in Figure 1, the UK has seen an even more pronounced fall in the number of main market domestic listed companies. This decline has partly been driven by a substitution effect towards the AIM market (the LSE’s junior market segment for small and medium-sized growth companies) from 1995 onwards. However, after accounting for this, there has been a clear decline in the overall number of domestic listed companies per capita after 2008 (the dotted line in Figure 1).

Why do firms seek to list?

When thinking about future trends in European equity markets, as well as potential policy implications, it can help to revisit the decision to list from the perspective of the firm.

Ultimately, the choice to list is a function of the benefits and costs of listing relative to alternative sources of finance and governance models. The owners of the firm will choose to list if the benefits of listing outweigh the costs.

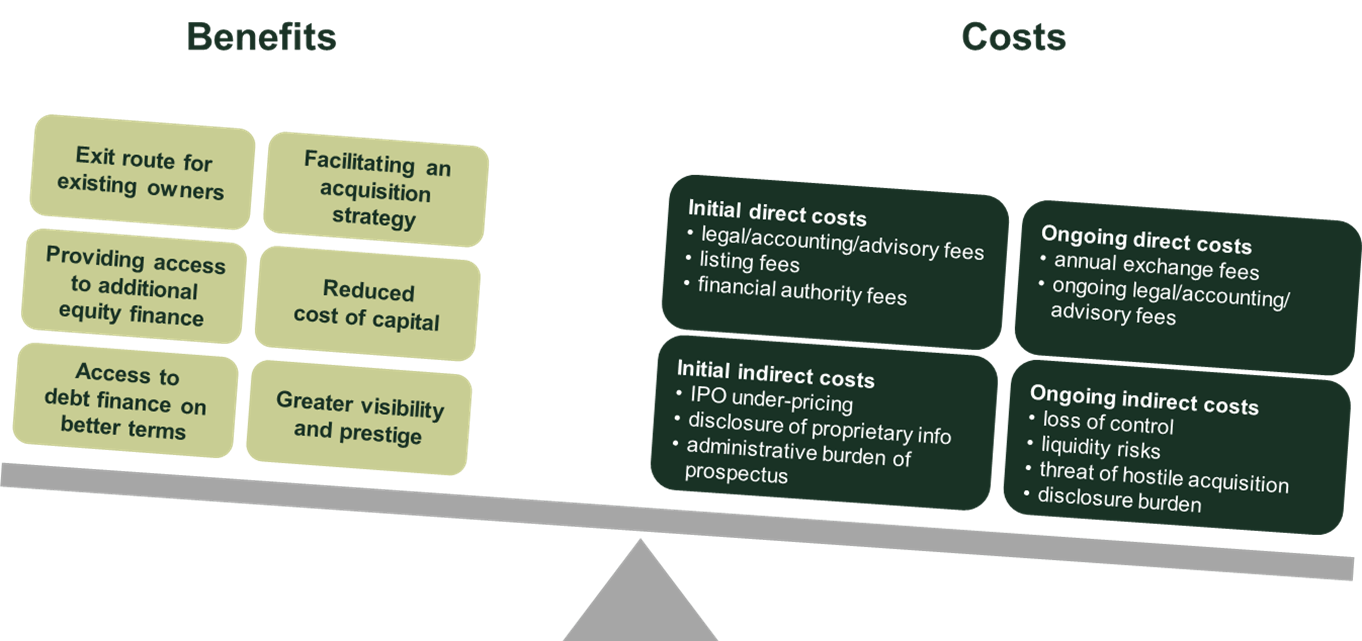

Figure 2 summarises the main costs and benefits associated with listing, based on a review of the academic literature and our interviews with a range of EU listed companies.

Figure 2 Costs and benefits of listing

Our analysis highlighted that the chief reasons for listing for EU firms are: (1) to provide an exit route for existing shareholders, (2) to facilitate an acquisition strategy, and (3) to access additional equity finance.4 For some companies, enhanced recognition or reputation is also an important consideration.

Companies trade off these benefits against the initial and ongoing costs associated with being listed. These costs can be both direct (e.g. listing or advisory fees) and indirect (e.g. under-pricing, disclosure burdens, and costs associated with control).

Why is the public market shrinking?

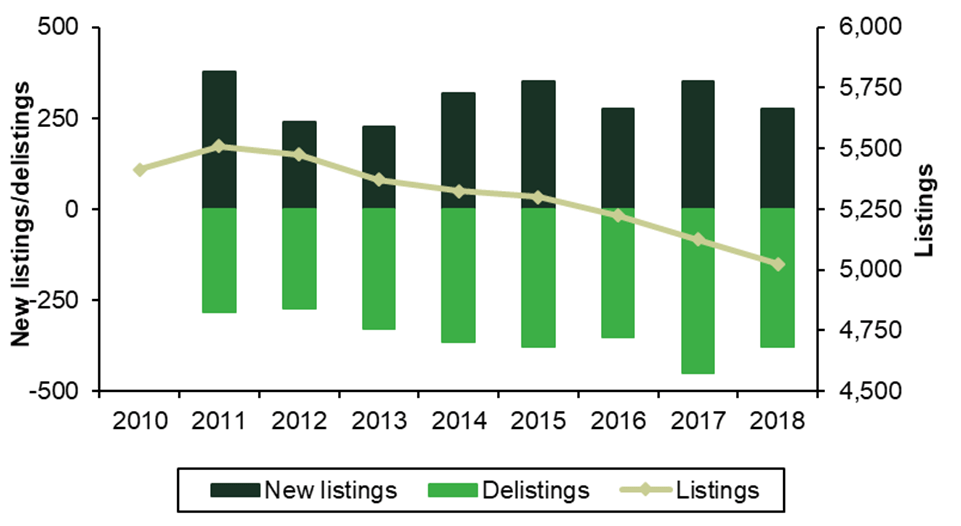

The only way there can be a fall in the number of listed companies is if the number of companies exiting public markets exceeds the number of new listings. This has been the case in the EU in the past decade, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Number of listed companies in the EU-27, 2010–18

Source: Oxera analysis of stock exchange data; WFE.

A relevant policy question here is: what is driving the fall in listed companies—too few listings, or too many delistings?

As discussed above, fewer companies will choose to list if the relative costs exceed the benefits. Feedback from the market indicates that the initial and ongoing costs of becoming a public company have risen considerably in recent decades, both in absolute terms and relative to private companies. We estimate the total financial costs of listing to be in the region of 5–15% of gross proceeds, and typically more for those raising smaller sums.5

While regulation may not be a primary driver for the decline in listings, the regulatory costs associated with listing are particularly relevant for smaller issuers, for which alternative private funding options are less readily available.

Developments in private equity markets have reduced some of the benefits of listing. For example, as the extent of private equity funding has increased, and with companies staying in private equity hands for longer, the IPO exit route has been less common.6

Data from the major EU exchanges indicates that delistings have predominantly been driven by increased M&A activity.7 Some delistings have been the result of acquisitions by companies that are already listed. Some delistings have also resulted from the acquisition of listed companies by private equity, alongside some technical delistings.

Policy implications

Relative to public markets, private markets have become significantly more attractive in recent decades. Should policymakers care?

For many companies, staying private makes sense. For others, the listing on public markets reduces the company’s cost of capital and allows them to scale up—supporting jobs, growth and market discipline in Europe at a time when this is much needed.

In one sense, this shift reflects the thriving nature of private capital markets: the developments in private equity, bond markets and non-bank lending offer a wide variety of financing options.

However, there are costs to having so few companies in the public domain. As well as the impact on efficient price formation and market discipline, there is a social policy dimension to this, as public markets democratise wealth creation.

While pension funds and insurers can invest in private companies, the general public cannot. Passive investors using indices have access to increasingly fewer companies and, as a result, may see smaller returns on their investments if more wealth creation occurs in private markets, pre-IPO. For this reason, among others, US regulators are considering whether private equity could be included in individuals’ defined-contribution pension plans.8

There are different ways to develop equity markets in the EU—such as by rebalancing the relative attractiveness of public markets relative to private markets, and/or embracing the development of private equity markets—each requiring different policy choices depending on the political inclinations of policymakers.

Public equity markets are a type of platform, on which the buyers and sellers are investors and investees in shares of companies. Platforms need to attract buyers and sellers, and succeed as more buyers and sellers join. Balancing the interests of investors and investees is therefore important in setting policy proposals.

Our study for the European Commission identifies five key areas to boost public equity markets:

- revisiting the rules around disclosure to reduce the imbalance between private and public companies—for example, by evaluating the incremental benefits of disclosure requirements for secondary listings, of quarterly and half-yearly reporting requirements, and reconsidering the merit of the exemption for unlisted companies from some non-financial reporting requirements, such as those related to environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations. Policies to support the development of junior market segments are also important, as they reduce the minimum efficient scale for listing;

- encouraging flexibility in the use of control-enhancing mechanisms where national rules or practices prevent this. One approach is to allow companies to issue various types of shares (with different voting rights) on a time-limited basis, to encourage more family-owned firms to seek a listing on public markets without owners having to relinquish control.9 Over 4,600 family-run companies above €50m in size remain unlisted in 14 EU member states:10 this could be a significant source of new listings;

- promoting institutional investor participation in IPOs—by reconsidering regulatory costs or restrictions on pension funds, insurers, and possibly other financial firms investing in public equity markets.

- improving corporate governance standards to keep down agency costs. In countries where ownership is fragmented, reducing impediments to the control of blockholders (i.e. those investors who own a large amount of shares) may make the ownership of a public company relatively more appealing;

- attracting retail investors—a potentially large source of capital—to invest in public equity markets. Policymakers could require underwriters of the IPO process to use technology to make a small proportion of allocations directly available to retail investors. There are examples of this in Singapore and Hong Kong; and in Australia the technology has been considered, but has not yet been implemented.11 For smaller stocks, policymakers could explore whether lighter regulation could catalyse the development of investment vehicles focused on small and medium-sized enterprises.

Public markets represent the outcome of a complex value chain requiring successful interactions between issuers, exchanges, advisers, brokers, banks, investors, and the like. These interactions can give rise to coordination failures and outcomes that could be improved. When considering interventions, policymakers should ensure that the individual actors’ incentives are aligned to produce the desired outcome. This can only happen if the operation of the EU’s equity markets is considered in the round.

1 Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November, Figure 1.1.

2 Jensen, M. (1989), ‘The Eclipse of the Public Corporation’, Harvard Business Review, 67:5, pp. 61–74.

3 This was calculated by comparing the actual number of listed companies to a prediction based on a cross-country econometric model, taking into account factors such as GDP and corporate governance standards. See Doidge, G., Karolyi, A. K. and Stulz, R. M. (2017), ‘The U.S. listing gap’, Journal of Financial Economics, 123:3, pp. 464−87.

4 As part of our study for the European Commission, we spoke to around 300 market participants across Europe, and conducted a survey of issuers.

5 Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November.

6 Recent data shows that European (EU and non-EU) private equity IPO values in 2019 were at their lowest levels since 2012, although the fall in IPO exits has been offset by an increase in private equity sales to corporates. See PitchBook (2020), ‘European PE breakdown: 2019 Annual’.

7 For the European data, see Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November, Figure 4.9. In the USA, Doidge, Karolyi and Stulz attribute the fall in US listings per capita to a historically high level of acquisitions of US-listed companies. See Doidge, G., Karolyi, A. K. and Stulz, R. M. (2017), ‘The U.S. listing gap’, Journal of Financial Economics, 123:3, pp. 464−87.

8 See, for example, SEC (2020), ‘Private Investment Sub-Committee Update: SEC Asset Management Advisory Committee – 16th September 2020’.

9 The advantage of introducing control-enhancing mechanisms is to reduce agency costs typically associated with fragmented ownership. However, the elimination of one market failure may give rise to another. Owners, even if they do not have a majority share in the company, can derive private benefits of control from such control-enhancing mechanisms, such as the power to appoint friends to the Board and other management positions, or the ability engage in related-party transactions. This change of control should be priced into the value of the shares by investors. This trade-off has led to calls for control-enhancing mechanisms to include sunset clauses after a fixed period of time, unless approved by shareholders. See Bebchuk, L. A. and Kastiel, K. (2017), ‘The untenable case for perpetual dual-class stock’, Virginia Law Review, 103:4, pp. 585–631.

10 The 14 countries are Bulgaria, Croatia, Estonia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, and the UK. See Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November, Figure A5.1.

11 See Box 8.2 in Oxera (2020), ‘Primary and secondary equity markets in the EU’, November.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More