Regulating oligopolies in telecoms: the new European Commission guidelines

In February 2018 the European Commission published draft guidelines on determining significant market power (SMP) in electronic communications markets. This is one of several policy developments in the regulation of these markets, which are increasingly oligopolistic rather than monopolistic. What are some of the new (and old) issues raised by these developments?

Telecommunications markets across Europe have seen significant change in recent years. The deployment of next-generation access (NGA) networks, competition from cable networks, technological convergence, and a wave of mergers and acquisitions in the sector have contributed to the emergence of ‘oligopolistic’ markets: a small number of competitors using their own infrastructure to offer bundles of fixed, TV and mobile services.

In September 2017 Oxera published a discussion paper that reviewed a large body of empirical evidence on infrastructure competition among cable, copper and mobile networks.1 A crucial finding of this review was that competition was the main driver of investment in NGA networks and innovation, while also delivering good outcomes to consumers such as higher penetration of broadband services, speed and coverage, and competitive prices.

The policy developments since the publication of that discussion paper include the European Parliament and Council’s presentations of their respective amendments to the European Electronic Communications Code proposals, and the European Commission’s publication of draft revised SMP guidelines.2

The draft guidelines set out the main principles and criteria for determining single-firm SMP and joint SMP. As such, they are general in nature, and the devil will be in the detail of how national regulators apply them in specific cases. In this regard, Oxera has made a further contribution to the debate through a supplementary discussion paper commissioned by Liberty Global.3 This paper is relevant for when regulators carry out SMP-specific assessments, and its key findings are summarised in the box.

Key findings of Oxera’s supplementary discussion paper

- It is not sufficient in SMP assessments to show the existence of a higher static (short-term) price and conclude from this that there is a market failure that might indicate joint SMP. Given that price is just one of many dimensions of competition and consumer outcomes, intervening could be thought of as a transfer of surplus from ‘tomorrow’s’ consumers to ‘today’s’ consumers.

- Suggestions that refusal to supply access could be a leading indicator of tacit collusion, or might be enough to show consumer harm at the retail level, are incorrect and would result in an undue lowering of the threshold for intervention.

- The requirement for ex ante analysis is not in itself a reason to put more emphasis on structural elements (for example, the number of operators in the market), and as such an analysis will inevitably be incomplete. An integrated approach that takes into account behavioural factors (i.e. assessing how competition works among existing operators) remains appropriate.

- A forward-looking ex ante SMP assessment that controls for the effects of pre-existing ex ante regulation but takes into account regulation in related markets—the modified Greenfield approach1—is required in order to correctly identify the counterfactuals and the theories of harm that need to be remedied using regulatory tools.

- The theories of harm related to joint SMP are likely to be different from in the past, where the market was characterised by single SMP.

Note: 1 The modified Greenfield approach is included in the European Commission’s 2014 Recommendation on relevant product and service markets within the electronic communications sector susceptible to ex ante regulation.

Source: Oxera (2018), ‘Regulating oligopolies in electronic communications markets’, supplementary discussion paper prepared for Liberty Global, January.

Recent policy developments

Oxera’s first discussion paper provided extensive evidence in response to the European Council’s suggestion that the SMP framework based on the SMP guidelines is insufficient to guarantee effective competition in all circumstances.4

The relevant question for policymakers is not simply whether an enforcement gap exists, as this provides little guidance for good policymaking. Rather, the relevant question concerns what the size of the gap needs to be for intervention to occur, and also whether ex ante regulation is the answer (weighing up the costs and benefits). Only then is it possible to assess whether additional ex ante regulation is appropriate.

The first discussion paper concluded that the concept of UMP (unilateral market power) proposed by the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) in 20175 would be unworkable in practice, since it remained unspecified and open to interpretation. In particular, the proposal by BEREC to include UMP in addition to SMP in the regulatory framework would mean that regulators would be able to intervene in markets that are more competitive than ones in which SMP can be found, but not as effectively competitive as the regulator would like. The legal uncertainty caused by such a test would be significant. The UMP concept does not appear in any of the recent proposed amendments to the Code, and nor is it mentioned in the Commission’s draft revised SMP guidelines.

However, other developments raise a number of issues that continue to be debated by policymakers. This article addresses the following.

- The suggestion by BEREC that the standard of proof for finding joint dominance under the SMP framework is too high and that (high) prices and profits are indicators of market failure.6

- The suggestion by the European Parliament that refusal to supply wholesale access on terms that remain unspecified (in conjunction with high rents downstream at a level that also remains unspecified) could be evidence of joint dominance.7 The Commission’s draft SMP guidelines also refer to this concern.8

The role of price in analysing market outcomes under oligopolistic competition

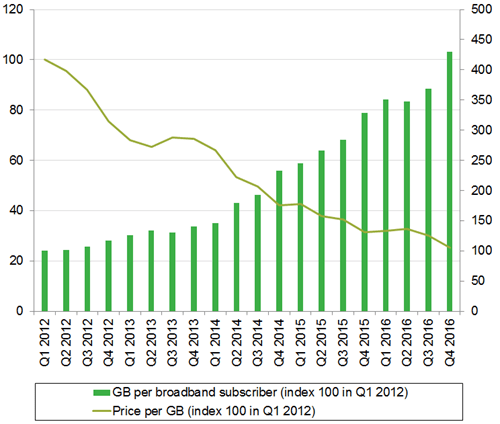

A wide range of differentiated retail offers are available in the telecommunications market, with multiple quality dimensions that evolve over time. For example, inclusive Gigabyte (GB) data allowances across Europe have been increasing over time while prices (per GB per broadband subscriber) have fallen. Figure 1 illustrates the case of Belgium.

Figure 1 Fixed broadband price per GB and GB usage per broadband subscriber in Belgium, 2012–16

Given the multidimensional and dynamic characteristics of competition, regulatory intervention based on the finding of a market failure according to a subset of indicators may not benefit consumer outcomes in the long run. In particular, focusing primarily on short-run price levels ignores the dynamic aspects of competition and consumer benefits—such as investments in network upgrades and new technologies, product and service innovation, and the quality of service and experience enjoyed by consumers.

Even where prices appear to be high (for example, based on comparisons across member states)9 or have been trending upwards after remaining at low levels for a long time, there needs to be an assessment of whether this is justified by investment levels and/or improvements in quality of services (such as larger data allowances or faster speeds) in a given market.

A conclusion that a particular level of price is ‘too high’ or ‘excessive’ based on a comparison with costs may not be appropriate. There are many reasons why prices may deviate from costs over a given time period, without this being inconsistent with competitive market dynamics. For example, investments are often lumpy, whereas prices are (typically) more stable. As a result, a snapshot in time may show a large deviation between prices and costs (or profits and the cost of capital), without this being indicative of a competition problem. It is therefore also important to look at profitability over a longer time horizon.

The Commission’s draft SMP guidelines highlight that, in terms of joint SMP, coordinated behaviour is easier in less complex and more stable economic environments.10 In this regard, the multidimensional and dynamic characteristics of competition in electronic communication markets, and the fact that infrastructure operators compete using different technologies (for example, cable and copper-fibre network operators come from different core-product backgrounds and enjoy different comparative advantages), make it difficult to coordinate on retail prices. Furthermore, even if alignment of prices on a small number of flagship products is possible,11 this does not automatically mean that competition on other service attributes is weak.

The role of (regulated) wholesale access under oligopolistic competition

Economic theory and the empirical evidence show that oligopolies come in many flavours. Even two-player markets can be highly competitive—with technology-leapfrogging and rapid product and service innovation by competing networks. This is the result of high product substitutability, asymmetric cost structures, and technological cycles.

The Commission’s draft SMP guidelines state that ‘a refusal by network owners to provide wholesale access on reasonable terms may be a potential focal point of a common policy adopted by members of an oligopoly’.12

However, in practice, the lack of credible punishment mechanisms at the wholesale level (access deals are infrequent) means that collusion at the wholesale level is unlikely to occur unless there is also a credible punishment mechanism at the retail level. Indeed, the Commission’s draft SMP guidelines suggest that short-term price wars in related retail markets could be a credible retaliatory mechanism when the focal point for coordination consists of refusing to supply access.13

Nevertheless, a closer examination of this logic reveals that, in fact, refusal to supply access cannot be a focal point of coordination on its own, since oligopolists also need to coordinate on keeping retail prices high in order to use the threat of a price war as a credible deterrent. In other words, coordination at the wholesale level (refusing to supply access) is a strategic instrument that provides stability to the coordinated outcome at the retail level. It is therefore unlikely that joint refusal to supply access alone can be a leading indicator of tacit collusion.

This ‘coordination of coordination’ at both levels of the supply chain is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Retail coordination depends on wholesale coordination, and wholesale coordination depends on retail coordination

![a cycle: wholesale coordination (to prevent disruption from access seekers), [arrow implying "leads to"] requires ability to punish deviations in retail market (given lack of credible punishment in wholesale market), [arrow implying "leads to"] requires high retail market profits (above competition Nash equilibrium levels), [arrow implying "leads to"] requires retail co-ordination, [arrow implying "leads to"] first point](https://www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Agenda-February-18-regulating-oligopolies-figure-3-1.png-1.png)

Although wholesale access can provide additional competitive constraints, its absence is not necessarily indicative of a lack of competition (e.g. as a result of coordination), and should not be automatically associated with higher prices and slower upgrades. The important question is whether the competitive constraint provided by access seekers using regulated wholesale offers is likely to be material in a particular case.

In this regard, there is a danger of overstating the challenges with undertaking ex ante SMP assessments. Challenges with forward-looking analysis are not unique to the SMP framework. As a first step, it should be possible to analyse whether the competitive constraint provided by access seekers using regulated wholesale offers is likely to be material in a particular case. Under the modified Greenfield approach, this would involve analysing a counterfactual of no regulated access (but, for example, taking into account obligations resulting from approval of merger transactions), and assessing whether competition continues to deliver good consumer outcomes.

Any forward-looking market review should also consider that there is likely to be increasing infrastructure competition from the development of next-generation mobile networks (5G), the growing coverage of cable networks and alternative (fibre access) networks, and the deployment of fibre networks utilising the passive infrastructure of utility providers (such as electricity and water companies).

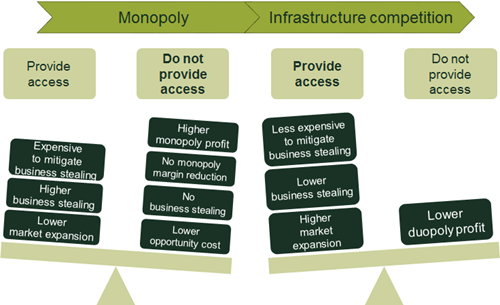

Commercial and competitive incentives to provide wholesale access in the absence of regulation

If the wholesale broadband market is deregulated, a decision about whether to intervene in retail competition would also need to consider whether infrastructure operators are likely to supply wholesale access on a voluntary basis—and the competitive dynamics introduced in the market by such commercial offers.14

Where there are two infrastructure operators rather than just one, there are often higher incentives for at least one of the infrastructure operators to provide access.

Consider first the incentives of a vertically integrated monopolist to supply access. A monopolist’s decision about whether to supply wholesale access will depend on how the wholesale profits from providing access compare with the impact on retail profits from providing such access. If the monopolist provides wholesale access it can earn wholesale profits, but it will face a competitor downstream that can steal retail customers from it. The impact on retail profits will depend on the volume of customers won by the access seeker and whether these customers are diverted from the infrastructure operator (business stealing) or are gained as a result of increasing sales that did not occur previously (market expansion).15

Now consider a situation where there is a competing infrastructure operator (even one that does not supply wholesale access). In this case, the access seeker’s business stealing effect is less harmful (muted) for the access provider (the former monopolist), and it is less expensive for it to mitigate the business stealing effect.

- The business stealing effect is muted because the access seeker attracts customers from the other infrastructure operator as well (this is equivalent to expanding the market for the wholesale access provider and is especially relevant if there is asymmetry in the retail offering of the two operators).

- It is less expensive for the access provider to mitigate the business stealing effect because retail margins in the market are lower than the monopolistic case as there is infrastructure competition. This means that the retail profits earned will be low regardless of whether the infrastructure operator decides to provide wholesale access.

This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3 Higher unilateral incentives to supply wholesale access in the presence of a competing infrastructure operator

An integrated approach and designing remedies to address specific theories of harm

Based on the discussion above, it is appropriate that an integrated approach following the well-established case law set out in the Airtours/First Choice case (and subsequent cases such as Impala)16 is followed in a regulatory context. The Commission’s draft SMP guidelines also refer extensively to this case law when setting out the principles for determining joint SMP.

The case law clearly states that joint dominance does not include any oligopolistic interdependence, but only interdependence involving tacit collusion. Greater focus on structural elements, and in particular a checklist approach, would therefore not be appropriate. This is acknowledged in the draft SMP guidelines.

Furthermore, when imposing ex ante regulation under the SMP framework, it is important that regulators clearly articulate the nature of the market failure that is present (or would be expected to be present) in the retail market absent any form of retail or wholesale regulation—i.e. the theory of harm that ex ante SMP regulation is intended to address.

In particular, remedies need to adapt to reflect the nature of competition in the market. This principle takes on particular significance where it is no longer obvious that there is just one firm with single SMP in the market, and the regulator is considering whether, nevertheless, there could be a situation of joint SMP as set out above based on the possibility that a subset of market factors might not work well in the future. It is beyond the scope of this article to propose what type of remedies may be suitable in these situations, and this does not (yet) seem to be covered in the Commission’s draft SMP guidelines or the new Code discussions. It will therefore fall on National Regulatory Authorities, BEREC and the Commission to define an appropriate and proportionate remedies package in oligopolistic markets.

1 Oxera (2017), ‘Regulating oligopolies in electronic communications markets’, discussion paper prepared for Liberty Global, September. See also the previous Agenda article: Oxera (2017), ‘Regulating oligopolies in telecoms: a solution in search of a problem?’, Agenda, September.

2 European Council, Council of the European Union (2017), ‘New EU telecoms rules – Council ready to launch talks with Parliament’, press release 574/17, 11 October. See proposed European Council amendments to Recitals 139–141 and 143, as well as amendments to Article 59(2) of the Code. European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February.

3 Oxera (2018), ‘Regulating oligopolies in electronic communications markets: supplementary discussion paper’, prepared for Liberty Global, January.

4 European Council, Council of the European Union (2017), ‘New EU telecoms rules – Council ready to launch talks with Parliament’, press release 574/17, 11 October.

5 BEREC provides the following definition of UMP: ‘An undertaking shall be deemed to have unilateral market power where, in the absence of significant market power, it enjoys a position of economic strength by virtue of the weakness of competitive constraints in an oligopolistic market, enabling it to act in a manner which is detrimental to consumer welfare.’ See BEREC (2017), ‘BEREC views on non-competitive oligopolies in the Electronic Communications Code’, BoR (17) 84.

6 BEREC (2017), ‘BEREC views on non-competitive oligopolies in the Electronic Communications Code’, BoR (17) 84.

7 European Council amendments to Recitals 139–141 and 143, as well as amendments to Article 59(2) of the Code.

8 European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February, para. 82.

9 The existence of many and evolving service permutations across member states and over time means that comparing prices for telecoms services is not a trivial exercise. For example, the level of competition, network topology, investment levels, availability of innovative services, quality of service, etc. vary across member states. Prices charged by different operators vary with these factors as well as with macroeconomic factors such as differences in income levels. This means that comparing prices across member states may not be an appropriate basis on which to decide whether prices in a particular member state are ‘high’.

10 European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February, para. 71.

11 European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February, para. 72.

12 European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February, para. 82.

13 European Commission (2018), ‘Guidelines on the market analysis and the assessment of significant market power under the EU regulatory framework for electronic communications networks and services’, February, para. 85.

14 By ‘wholesale broadband market’ we mean wholesale local access (Market 3a) and wholesale central access (Market 3b).

15 To the extent that the access seeker expands the market, this will result in additional wholesale profits for the infrastructure operator. To the extent that the access seeker steals business from the infrastructure operator, this will result in lower retail profits for the infrastructure operator. The monopolist can mitigate the business stealing effect by lowering its retail price, but this will also reduce its margin below the monopoly margin on all its sales.

16 Case T-342/99, Airtours v Commission, para. 62; and Case T-464/04, Impala v Commission.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More