State aid spotlight on tax: the General Court’s judgments on Fiat and Starbucks

In 2015, the European Commission ordered Starbucks and Fiat to each pay €20m–€30m in the Netherlands and Luxembourg, respectively, as their tax arrangements were found to constitute illegal state aid. On 24 September 2019, the General Court upheld the Commission’s Fiat decision, but annulled the Starbucks decision. What were the key economic issues in these cases, and what are the implications of the judgments?

Since 2014, there have been a number of high-profile state aid investigations by the Commission into multinationals’ corporate tax arrangements in a number of EU member states. While the application of state aid rules to corporate taxation is not new, the investigations have been the subject of significant debate.1

Following appeals of the Starbucks and Fiat decisions, on 24 September 2019 the General Court upheld the Commission’s Fiat decision, but annulled the Commission’s Starbucks decision.2

The General Court’s judgments provide clarification regarding the economic and financial framework that is used to assess whether tax arrangements confer an advantage on the companies under investigation.3 In this article, we discuss the framework adopted and the General Court’s conclusions, as well as the implications of the judgments for how companies could mitigate state aid tax risks.

Do tax rulings confer an economic advantage? The application of the arm’s-length principle

The General Court upheld the Commission’s use of the arm’s-length principle to assess whether intra-group transactions, and hence the level of taxable profit, are on market terms.4 That assessment is based on the OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines, which were last updated in July 2017 and represent an internationally agreed standard for transfer pricing.5 The OECD’s Transfer Pricing Guidelines are designed to ensure that the outcomes of intra-group transactions between different entities of a multinational are in line with those that would be observed between independent entities.6

However, as noted by the General Court, the arm’s-length principle is only approximate in nature. In order to conclude that a tax ruling confers an economic advantage, according to the General Court, it would need to be shown that the terms and conditions fall outside a reasonable approximation of what is implied by an arm’s-length pricing method.7

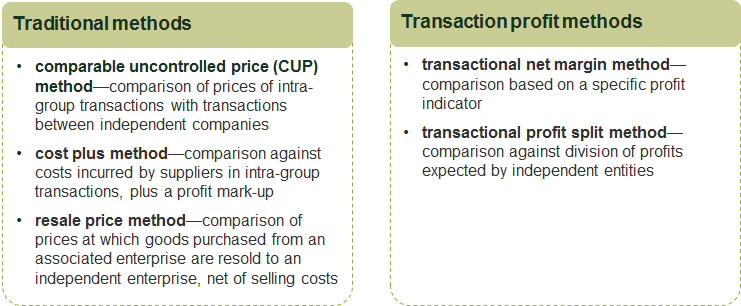

The OECD Guidelines outline five methods to approximate the arm’s-length principle (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Overview of the OECD’s methods to approximate the arm’s-length principle

Among these methods, the Commission has expressed a preference for the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method, which involves comparing the prices of intra-group transactions with the prices of transactions between independent entities.8 However, the Commission also noted (in the Fiat case) that, as the CUP method is not always applicable, other methods, such as the transactional net margin method (TNMM), can be used instead.9 The TNMM involves comparing the profit indicator that is used to calculate taxable profit with those observed in independent transactions (see the box below).

The steps to apply the TNMM

The TNMM method is usually applied as described below.

- Choice of the tested party. The first step is to select the entity (i.e. the tested party) on one side of the transaction within the multinational for which it is possible to benchmark the profit margin earned in the transaction against the profit margin earned by comparable independent companies in similar transactions. The tested party is typically identified by analysing the functions, assets and risks of the different parties to the transaction.

- Choice and estimate of the profit-level indicator. A financial indicator (such as a profit margin) that reflects the activities performed by the entity is required. If it can be robustly demonstrated that the financial indicator for an entity within the corporate group is in line with those observed in transactions between independent companies, the transaction can be deemed to be on an arm’s-length basis.

Source: OECD (2010), ‘Transfer Pricing Guidelines 2010’, para. 3.18.

Why did the General Court annul the Commission’s conclusion that the tax ruling conferred an economic advantage on Starbucks?

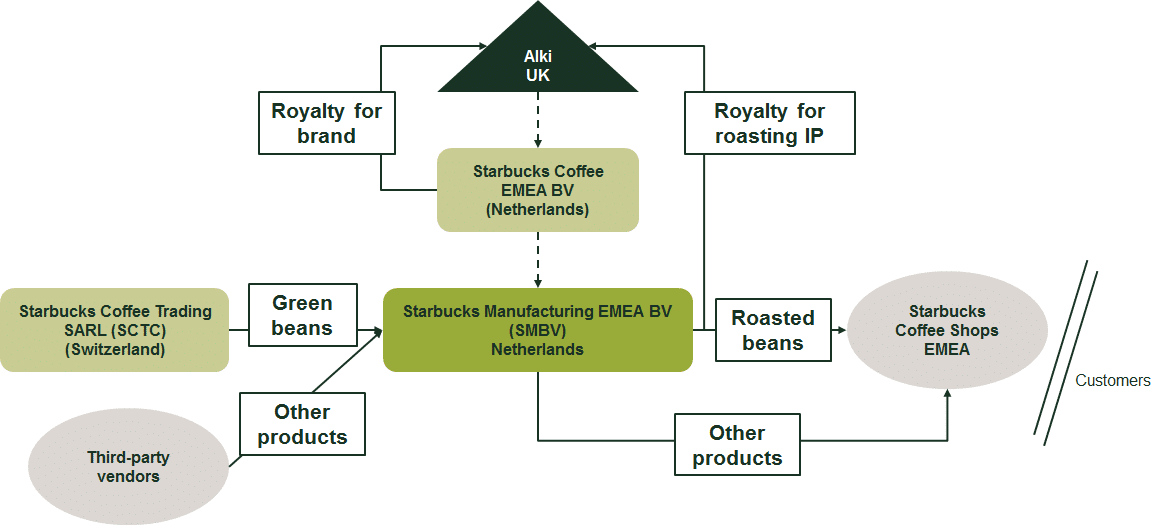

In the Starbucks case, the Commisson’s investigation focused on the Advance Pricing Agreement (APA) between the Netherlands and Starbucks Manufacturing EMEA BV (SMBV). SMBV is a subsidiary of the Starbucks group in the Netherlands that processes green coffee and sells roasted coffee to both Starbucks and independent third parties (see the Figure 2 below for further details).

The APA set out the following methodology for determining SMBV’s taxable profit in the Netherlands from its production and distribution activities.

- It used the TNMM methodology—i.e. a profit margin on SMBV’s eligible operating costs—to calculate SMBV’s taxable profit. The eligible operating costs excluded the costs of cups, paper napkins, green coffee beans, and payments for logistics and distribution activities for services provided by third parties;10

- The eligible costs used for calculating SMBV’s taxable profit also excluded the royalty payments from SMBV to Alki, an entity of the Starbucks group based in the UK, for the use of coffee blends and coffee roasting technology (the roasting IP). The royalty payments that were made by SMBV were calculated as the difference between SMBV’s realised operating profit from its production and distribution functions and the estimate of the taxable profit that was derived from the TNMM.11

The APA did not stipulate the price at which SMBV would purchase green coffee beans from Starbucks Coffee Trading SARL (SCTC), a subsidiary of the Starbucks group based in Switzerland.12

Figure 2 Overview of the arrangements between SMBV and other entities of the Starbucks group

The Commission concluded that the methodology set out in the APA conferred an economic advantage on Starbucks, as it allowed Starbucks to underestimate its taxable profits. In contrast, the General Court determined that the Commission had failed to demonstrate that the APA conferred an economic advantage, and annulled the Commission’s decision. Specifically, in its assessment of whether the APA conferred an economic advantage, the General Court reached different conclusions from the Commission in three areas, as we discuss below.

Were the royalty payments on an arm’s-length basis?

The Commission concluded that the methodology adopted for determining the royalty payments by SMBV for the use of the roasting IP was not in line with the arm’s-length principle, and that the variable nature of the payments suggests that they were not related to the value of the IP.13 The Commission also argued that the CUP method should have been used instead of the TNMM in order to estimate the applicable royalty payments.14 Based on agreements between Starbucks and third parties, as well as agreements between Starbucks’s competitors and third-party roasters, the Commission concluded that SMBV should not have paid any royalty.15

However, the General Court noted that the OECD does not express a preference for the use of the CUP method over the TNMM. The General Court concluded that the Commission had not shown that the choice of the TNMM led to an over-estimation of the royalty payments to be made by SMBV (and hence, an under-estimation of SMBV’s taxable profits in the Netherlands).16 According to the General Court, the Commission had incorrectly compared SMBV’s activities against those of companies that were not sufficiently similar, and the Commission had incorrectly used information on contracts concluded subsequent to the APA.

Did SMBV pay the market price for purchasing green coffee beans?

The Commission concluded that, from 2011 onwards, SMBV paid above the market price for green coffee beans, which led to lower taxable profits for SMBV. According to the Commission, Starbucks had not provided any ‘valid’ justification for the increase in the price from 2011 onwards.17

However, the General Court noted that the Commission did not explain how the increase in the price from 2011 onwards could have been foreseen at the time of adopting the APA.18 Furthermore, the General Court highlighted that the Commission had not compared the price paid for the coffee beans with the price paid by a stand-alone roaster in a comparable situation, and had not demonstrated that the price exceeded the market level.19

Did the APA implement the TNMM appropriately?

The Commission argued that, even if it had been appropriate to apply the TNMM, there were a number of errors in its implementation in the APA. However, the General Court disagreed with the Commission for the following reasons.

- The choice of the tested party. According to the Commission, SMBV had been incorrectly identified as the tested party.20 However, the General Court concluded that the Commission had not shown that applying the TNMM to Alki (and allocating the residual profits to SMBV) would have led to higher taxable profit for SMBV.21 The Commission had also not demonstrated that more reliable data was available to apply the TNMM to Alki.22

- The choice of the profit-level indicator. The Commission had concluded that, instead of using a return on operating costs as the profit-level indicator, sales should have been used, which would have led to higher taxable profit, as sales had increased more quickly than operating costs.23 The General Court, however, concluded that, even if it could have been foreseen at the time of signing the APA that SMBV’s sales would increase more quickly than its operating costs, the Commission had not shown that it was inappropriate to use a profit indicator based on operating costs.24

- Estimates of the profit-level indicator. The Commission’s arguments that the comparators used to estimate the profit-level indicator were not appropriate were dismissed by the General Court, on the basis that the comparator companies selected by the Commission were sufficiently different from the Commission’s own description of SMBV’s main functions.25

Why did the General Court uphold the Commission’s conclusion that the tax ruling conferred an economic advantage on Fiat?

In contrast to its conclusion in the Starbucks case, the General Court upheld the Commission’s decision that the tax ruling conferred an economic advantage on Fiat.

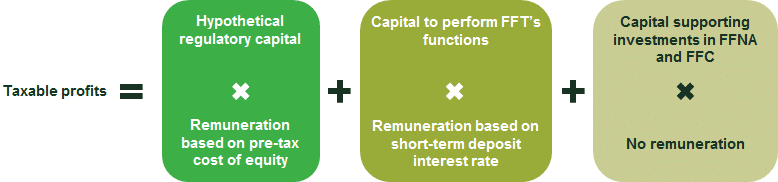

The tax ruling between Luxembourg and Fiat Chrysler Finance Europe (FFT), an undertaking in the Fiat group that provides treasury and financing services to group companies in Europe, set out the following two steps to derive FFT’s taxable profits, based on the TNMM (see also Figure 3 below):

- a ‘risk remuneration’, calculated by multiplying FFT’s hypothetical regulatory capital by an expected return of 6.05%;

- a ‘functions remuneration’, calculated by multiplying FFT’s capital used in performing its functions by the market interest rate applicable to short-term deposits.

The taxable profits excluded any return on FFT’s equity that supported FFT’s financial investments in Fiat Finance North America (FFNA) and Fiat Finance Canada Ltd (FFC).26

Figure 3 Illustration of the estimation of FFT’s taxable profits

Unlike in the Starbucks case, there was no debate about whether the TNMM represented the appropriate arm’s-length pricing methodology.27 Instead, the debate focused on the choice and estimation of the profit-level indicator.

What was the appropriate profit-level indicator?

The General Court agreed with the Commission that FFT’s hypothetical regulatory capital did not constitute the appropriate profit-level indicator to determine the taxable profits of FFT’s intra-group financing and treasury activities, as regulatory capital represents the minimum capital that FFT is required to hold.28 In line with the Commission, the General Court concluded that FTT’s accounting equity should have been used, which was reported to be ten times the level of FFT’s hypothetical regulatory capital.29

What was the appropriate estimate of the profit-level indicator?

The General Court agreed with the Commission that the segmentation of FFT’s equity capital, to which different rates of return were applied, did not approximate the arm’s-length principle.30

The General Court also agreed with the Commission that it was incorrect to exclude the remuneration of FFT’s equity underpinning its investments in FFNA and FFC. It was concluded that this led to FFT’s capital base being significantly underestimated by almost 60%.31

What are the implications of the General Court’s judgments? How can state aid risks be mitigated?

The economic and financial issues raised by the General Court, and by the Commission in both cases, include the determination of royalty payments and the choice and application of the OECD arm’s-length pricing approach.

The General Court’s judgments highlight the importance of ensuring that the arm’s-length pricing method is supported by robust contemporaneous economic and financial evidence at the time when the tax ruling is agreed.

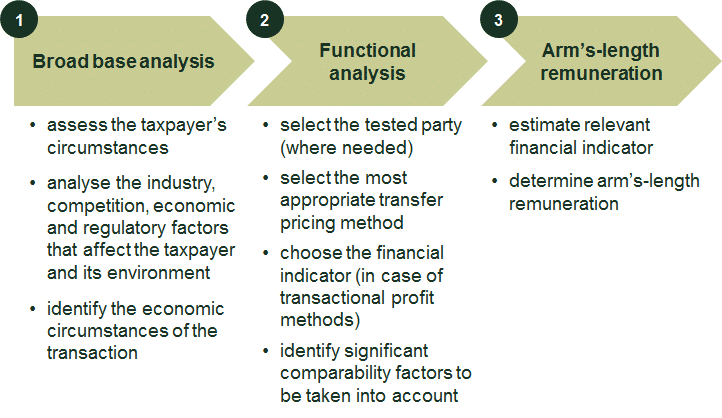

The main steps from the OECD’s Guidelines are summarised in Figure 4 and are discussed further below.

Figure 4 The main steps from the OECD’s Guidelines

- Broad base analysis. The first step is to assess the key factors that affect the taxpayer’s circumstances, such as the competition, economic and regulatory framework and the contractual arrangements between the parties.

- Functional analysis. The next step is to identify the functions, assets and risks of the relevant entities of the multinational to select the most appropriate transfer pricing methodology and to determine how the methodology should be applied (e.g. the identification of the tested party). For example, in the Starbucks case, the Commission argued that the functional analysis had been undertaken incorrectly, which, according to the Commission, resulted in the incorrect choice of operating costs as the profit-level indicator.32 However, the General Court did not conclude on the appropriateness of the definition of SMBV’s main functions, on the basis that the Commission had not demonstrated that the use of operating costs would not lead to an arm’s-length outcome.33

- Arm’s-length remuneration. The final step is to identify an appropriate comparator set in order to estimate the profit-level indicator. In both the Fiat and Starbucks cases, the Commission contested the comparator analyses produced by the companies, which highlights the importance of a robust analysis to identify the most appropriate comparators.

More cases on the horizon?

The General Court upheld the Commission’s approach of applying state aid rules to tax rulings based on the OECD’s arm’s-length pricing principles. Recently, European Commissioner for Competition, Margrethe Vestager, has announced that the state aid investigations into multinationals’ tax arrangements will continue, and that further information on tax rulings has been requested from member states.34

Although the Starbucks judgment, in particular, raises the bar in terms of the level of economic and financial evidence that must be provided by the Commission to demonstrate that a tax ruling confers an economic advantage, in the future, multinationals may see greater scrutiny from the Commission regarding the methodologies followed in tax rulings and the supporting contemporaneous evidence.

1 For an overview of the state aid tax cases, see Robins, N. (2019), ‘Tax rulings: an overview of EU state aid cases’, foreword to Concurrences e-Competitions Special Issue on tax rulings, 1 August.

2 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September; and Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September.

3 For a tax measure to constitute state aid, in addition to conferring an economic advantage on the companies in question, the following three conditions must be met: (1) it must be granted directly or indirectly through state resources and be imputable to the state (as the tax rulings are agreed with tax authorities, this is deemed to be met); (2) it must have the potential to distort competition and trade between member states (as the multinationals are typically based in a number of member states, this is often considered sufficient by the Commission to meet this criterion); and (3) the arrangements must be selective (as the rulings relate to specific multinationals, this criterion is also deemed by the Commission to be met). See Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, para. 385.

4 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, para. 172; and Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, para. 187.

5 The General Court points out, however, that the Commission is not formally bound by the OECD Guidelines.

6 OECD (2010), ‘Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations’, 16 August; and OECD (2017), ‘Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations 2017’, 10 July.

7 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, para. 207; and Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September‚ para. 199.

8 European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38374 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP)—Netherlands Alleged aid to Starbucks’, 11 June, para. 116.

9 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October, para. 246.

10 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, para. 15.

11 Ibid., paras 206 and 367.

12 Ibid., para. 53.

13 European Commission (2014), ‘State aid SA.38374 (2014/C) (ex 2014/NN) (ex 2014/CP)—Netherlands Alleged aid to Starbucks’, 11 June, paras 278, 289 and 317.

14 Ibid., para. 445.

15 The Commission also considered that SMBV did not benefit from the IP, and that the coffee-roasting activity did not generate sufficient profits to allow SMBV to make any royalty payments. See European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October, paras 291–309.

16 The General Court also argued that the Commission was incorrect to conclude that SMBV did not exploit the roasting IP directly on the market. See Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, paras 212, 215, 259, 265 and 346.

17 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, para. 46.

18 Ibid., para. 396.

19 Ibid., paras 398 and 401.

20 Ibid., para. 54.

21 Ibid., para. 430.

22 The General Court highlighted that, according to the applicable OECD Guidelines at the time, the tested party is the company for which the most reliable data on the most directly comparable transactions can be identified. See Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, paras 434 and 435.

23 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, paras 54 and 442.

24 Ibid., paras 467 and 468.

25 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, paras 478 and 492. The Commission had also argued that it was not correct to exclude costs associated with the resale of certain products from SMBV’s eligible costs. The General Court, however, concluded that the Commission had not demonstrated that SMBV generated profit from the resale of products, such as napkins and paper cups, and hence whether it was appropriate to exclude these costs. See Judgment of the General Court (2019), Cases T-760/15 and T-636/16’, 24 September, paras 523 and 540.

26 Sources: European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxembourg granted to Fiat’, 21 October; and Judgment of the General Court (2019), Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15, 24 September, paras 11 and 12.

27 As FFT concluded transactions with different counterparties of the Fiat group on different terms, the CUP method could not be applied. European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38375 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) which Luxemburg granted to Fiat’, 21 October, para. 246.

28 Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, para. 255.

29 In light of this, the General Court concluded that the appropriateness of the rate of return that was applied to FFT’s hypothetical regulatory capital base to calculate the taxable profits did not need to be assessed. Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, paras 281 and 282.

30 This was on the basis that FFT’s total equity would be taken into account if the company were to enter into insolvency. Judgment of the General Court (2019), ‘Cases T-755/15 and T-759/15’, 24 September, paras 222, 238, 241, 242 and 273.

31 Ibid., paras 244, 276, 273 and 274.

32 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October, para. 388.

33 European Commission (2015), ‘Commission Decision of 21.10.2015 on state aid SA. 38374 (2014/C ex 2014/NN) implemented by the Netherlands to Starbucks’, 21 October, para. 460.

34 Crofts, L., Acton, M. and McNelis, N. (2019), ‘Vestager asks EU governments for tax rulings info’, MLex, 8 October; and European Parliament (2019), ‘Answers to the European Parliament Questionnaire to the Commissioner-Designate Margrethe Vestager, Executive Vice-President-designate for a Europe fit for the Digital Age’, p. 16.

Download

Contact

Nicole Robins

PartnerContributors

Related

- Energy

- Financial Services

- Pharmaceuticals and Life Sciences

- Telecoms, Media and Technology

- Transport

- Water

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More