The Heathrow third runway: what next?

Given the approval of the UK government’s National Airports Policy Statement on 5 June 2018, observers may think that the last remaining major obstacles have been removed and the bulldozers are ready to roll in to clear the site for the third runway at Heathrow. But in truth, as Mike Toms, Oxera Director, explains, there are still many hoops to jump through before the project gets off the ground.

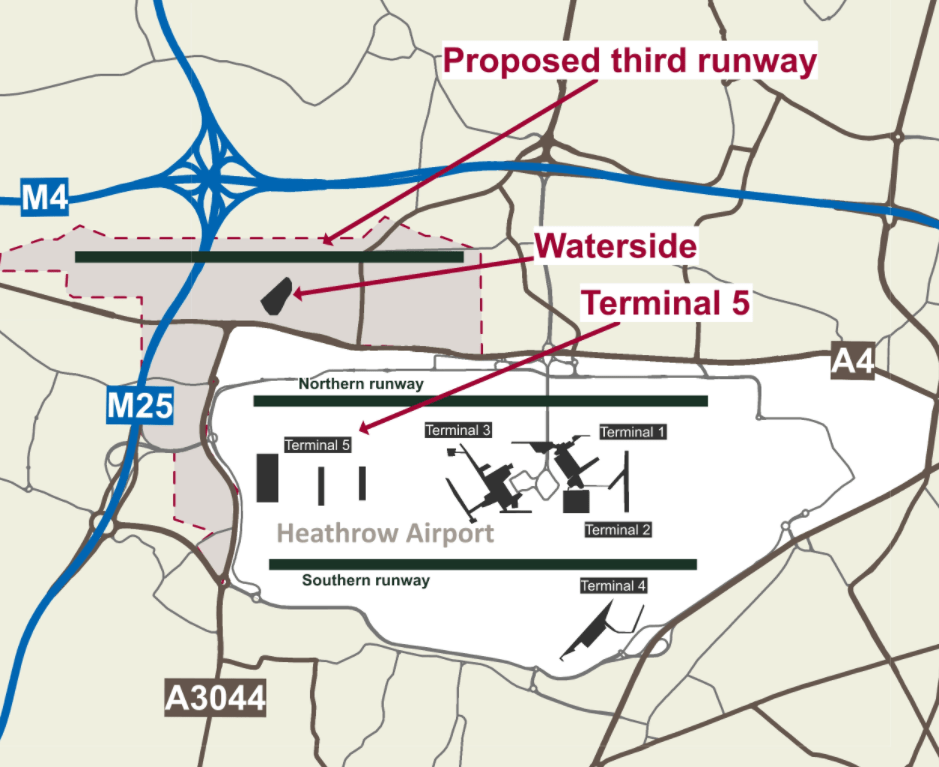

The first of these relates to the plan. Although the third runway was tabled by Heathrow as long ago as 2011, key elements are still undecided. We know the alignment of the runway, but we don’t know its length and, more significantly, we don’t know where the essential passenger terminal and aircraft parking capacity will go, or indeed how much car parking will be proposed and where. These are not trivial points; a number of options have been tabled. So far, each plan has had significant shortcomings, and the choice has major implications for the cost and impact of the scheme. The main features of the current airport and the proposed developments are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Heathrow Airport

Only when the overall master plan is resolved can the planners move forward with designing what will be large and complex structures and buildings. This will not be quick or simple. The architectural and engineering solutions will require much work.

At the same time, it is only when the master plan is firmed up that major decisions on road access can be made. We know that there will need to be a realignment of the M25 motorway along a stretch which currently carries around 20,000 vehicles in a typical hour. We also know that junction alterations will be needed from the M25 to the M4 and Heathrow’s Terminal 5. The A4 and A3044, which are key parts of the west London highway network and local access to the airport, will also be cut by the new runway, as will the airport’s main perimeter road. Some possible options have been presented for realignment of the A roads but there is nothing yet to show how a fully functioning local and regional road network will operate around the airport. Resolving these issues will almost certainly involve Highways England, Transport for London and local authorities.

At the same time, the Airport’s commitment that the runway will result in no increase in car traffic1 appears on the face of it to require the construction of new and complex rail schemes taking passengers from the airport west to Reading and south to Staines, where they will need to transfer to the existing main lines. In principle, both these schemes have been around for many years, but only the Heathrow West scheme is essentially fully planned, and neither has been financed or been submitted for formal development consent. The involvement of Network Rail and its approval of the schemes and their effects on timetables for existing services will be essential.

The Airport is now working on the principles which will underlie the changes to flight paths and procedures which will be necessary to operate three runways. When the principles are agreed, work will have to start on detailed airspace design and then the systems changes required to ensure the safe and efficient operation of a three-runway airport. When the work is sufficiently advanced, Heathrow will need to make an assessment of the likely airspace design to feed into updated estimates of the impact of the development on noise. This part of the project will lie in the hands of NATS (the UK air traffic control services provider) and the regulator, the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), and delivery will have to be integrated into broader long-term work on precision-based navigation.

Much work has already been done on other environmental impacts, but it has necessarily been quite ‘broad brush’ in the absence of a worked-up plan. When conclusions have been drawn on the points outlined above, the Airport will be in a position to undertake the full and detailed environmental appraisal which will be required before the plan can be submitted for a Development Consent Order (DCO) with minimum risk of a successful legal challenge.

While all this is happening, some tricky logistical issues will have to be resolved, mainly concerning the need to replace major pieces of infrastructure before the site can be cleared for work to start. Among these is the removal and replacement of Waterside, the headquarters of International Airlines Group, which is the parent company of British Airways (BA), Aer Lingus and Iberia. Waterside lies in the path of the runway, and is particularly important since it is also BA’s Heathrow base and the workplace for thousands of BA staff. New premises will have to be built or found for this huge, unique and complex building developed 20 years ago at a cost of £200m.2 Agreement will have to be reached with BA on how the switchover will happen to allow Heathrow to make the application for compulsory purchase of the site, which will need to accompany the DCO. Failure to deal properly with this challenge would pose a threat to the operation of Heathrow’s major passenger airline, which would be unthinkable. Lest this sounds straightforward, it is worth bearing in mind that the original development of Waterside took more than eight years.

At the same time, teams will no doubt be working on how to deal with the need to demolish, and possibly reconstruct, the major power station which also lies in the path of the runway, as well as a host of commercial, government and residential properties.

When clarity has been achieved on these issues, and allowing for the inevitable local and national consultations, the Airport will be in a position to submit its DCO application to the Planning Inspectorate. The process of approving the application is quite specific and should in theory be completed in around a year, but the clock cannot start in earnest until the preconditions for an application have been met.

But the approval of the DCO would not itself signify the firing of the starting gun. Even if the decision escapes legal challenge, two further practical challenges will have to be overcome before work can start in earnest.

The first is the delivery plan. The scheme will create massive upheaval both in the local area and in the operation of the airport itself, and there will be a need for careful and elaborate work-sequencing with a high level of resilience if chaos is to be avoided over a number of years. This will be particularly sensitive in relation to BA’s hub at Terminal 5. A programme will have to be worked out which allows continuing access to the terminal for more than 30m passengers a year, while all its motorway, A road and local vehicle accesses are being closed, diverted or realigned, and its railway station is being reconfigured for the new services to the west. Clearly all this cannot be done at once, and the maintenance of accessibility will have implications for the length of the construction programme.

And finally…there will have to be a mechanism for financing and remunerating the project and translating this into contracts. High-level work on this subject is already taking place. Heathrow, the CAA and the Department for Transport have all been turning their minds to how the project will work financially. Real deal-making will follow on from the greater clarity on cost and timing, which in turn can emerge only when the work outlined above is much closer to completion. At that stage, one can envisage a set of packages being assembled which involves landowners, contractors, current and new equity-holders, lenders, government, Highways England, Network Rail, NATS, BA, airline groups, utility providers and the CAA. And somewhere in this mix there will need to be a resolution to the current challenges from third parties that they, not Heathrow, should be given the opportunity to develop the scheme.

At that point the diggers can move in (although some enabling works may well have started in the meantime). How long will it take to build? Are claims correct that it might be completed as early as 2026?3 We know that the runway will be competing with HS2 for resources.4 It is not clear at this stage but, as a benchmark, the construction programme for Terminal 5—a rather smaller and simpler project—was around five years.

All of which leads to the economist’s quandary. As Danish physicist, Nils Bohr, is reported to have said, ‘Forecasting is difficult, especially forecasting the future.’ It would be a brave person who confidently forecasts if, when, and at what cost the third runway will open.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone. The UK government’s National Airports Policy Statement is available at Department for Transport (2018), ‘Airports National Policy Statement: new runway capacity and infrastructure at airports in the South East of England’, presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 9(8) of the Planning Act 2008, 5 June.

1 Department for Transport and The Rt Hon Chris Grayling MP (2017), ‘Airport capacity and airspace policy’, written statement to Parliament, 2 February.

2 Topham, G. (2016), ‘BA boss shocked to find out that third Heathrow runway will raze his HQ’, The Guardian, 23 November.

3 See BBC (2018), ‘Heathrow Airport: Cabinet approves new runway plan’, 5 June.

4 HS2, or High Speed 2, is a planned high-speed railway in the UK linking London, Birmingham, the East Midlands, Leeds and Manchester.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More