The right price for intellectual property rights: the debate continues

As discussed in a July 2017 Agenda article, we have recently witnessed an increased focus on cases involving alleged excessive pricing under competition rules in a wide range of sectors. This includes investigations by competition authorities (including the European Commission) and commercial disputes brought before courts.1

A number of these cases involve the pricing of intellectual property (IP) such as music copyright or standard essential patents (SEPs). A notable case in which the UK High Court issued a judgment earlier this year was Unwired Planet v Huawei, where the court assessed (and ultimately dismissed) excessive pricing allegations in the context of a commitment to license on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.2 Another case (AKKA/LAA) where the EU Court of Justice (CJEU) recently issued a preliminary ruling involving alleged excessive pricing by the Latvian collecting society for the remuneration of creators of musical works.3 In both cases, the question was whether the royalty rate being demanded by the IP-owner was excessive under competition law rules (and therefore an abuse of a dominant position), and/or whether it was otherwise unfair (e.g. under FRAND rules).4 So, how can the existing tests for excessive pricing be applied to the pricing of IP?

The legal framework for excessive pricing

According to case law, excessive pricing is where a price is ‘excessive in relation to the economic value of the service provided’ (General Motors, United Brands).5

In United Brands, the court set out that the test should include a comparison of the price of the product/service with its cost of production to assess whether the gap—i.e. the profit margin of the supplier—is high; and if it is, that a comparison should be made of the price imposed and the one charged for competing products.

However, other cases have found that the price–cost tests proposed in United Brands may not be sufficient for a finding of an abuse. This is because the economic value could be high due to customers’ willingness to pay for a specific feature, and this may not involve higher production costs. In other words, if a customer derives a high economic value from the product or service, then the supplier may be able to legitimately charge a high price, even if it involves high margins.

This approach was adopted by the European Commission in Port of Helsingborg, and by the UK Court of Appeal in Attheraces v British Horseracing Board.6 Under the approach, the key question for an excessive pricing assessment is whether the prices imposed distort downstream competition and harm consumers; or whether it is purely about the sharing of the total profits available in the value chain between the upstream supplier and the downstream player without there being a material impact on the downstream market.

For example, in British Horseracing Board, the court found that, even though the prices charged by British Horseracing Board could be seen as high and unfair, that alone did not indicate an abuse of dominant position. The key reason stated by the court was that the aim of competition law was to protect consumers, and there was no evidence that British Horseracing Board’s prices distorted competition in the market in which Attheraces operated.7

Fair pricing of IP: balancing creation and distribution

In an IP setting, the approach to assessing royalty rates depends on the market context and the legal framework used in a specific dispute or investigation. Specifically, in addition to competition law rules, other legal frameworks such as copyright law and, in the case of telecommunications patents, the FRAND rules of relevant standard-setting organisations, could be used to assess what constitutes a fair and reasonable royalty rate. For instance, the Latvian copyright case mentioned above used only competition law rules, while in Unwired Planet, Huawei alleged both a breach of the relevant FRAND rules and an infringement of competition law.

While a price–cost test could be used to assess allegations of excessive pricing or fairness/reasonableness in specific settings, in general the economic value approach adopted in British Horseracing Board is likely to be more relevant for IP. For example, one reason why cost-based tests may not be suitable is because the development of IP typically involves large fixed costs with high risk of failure, and the price that a specific IP commands often does not have a direct relationship with the cost of its development specifically (even if this component can be reliably estimated, which is often not the case). Nonetheless, profitability analysis may still be useful in such a setting, for example, to test whether the impact on the user of the IP is significant enough that downstream competition is distorted.

When considering the question of excessive or unfair prices in an IP context, it is critical to strike a balance between the creation of IP on the one hand, and the distribution or implementation of it on the other. This is because the total economic value generated from the IP (the ‘pie’) is driven by the quality of the invention embodied in the IP, as well as the extent and quality of its distribution/implementation through a final product that consumers value and are willing to pay for. Disputes about unfair or excessive royalty rates between the owners and users of IP are in essence about the division of this pie. In many cases, it also involves division of the pie among multiple ‘creators’ or ‘contributors’ to the total size of the pie (i.e. total economic value), only some of whom may own any IP. Some examples are given below.

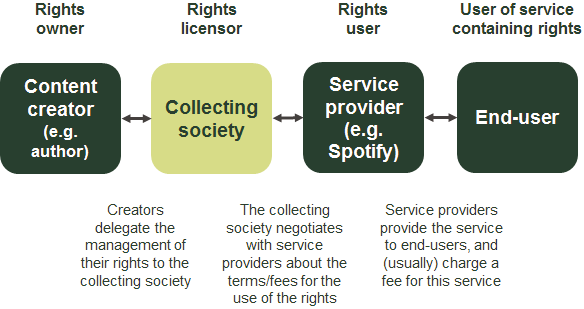

- In the context of copyrighted works such as music, the creation of total economic value starts with a rights owner, such as a songwriter or performer. However, it does not stop there. In fact, each entity in the value chain adds to the economic value of the work by transforming the creative work into products that are available to (and valued by) end-consumers. Ultimately, the total economic value of this final product is determined by consumers’ willingness to pay for it. The box below illustrates the supply chain for musical works and the value added by each layer of the chain.

- In the context of telecommunication standards such as 4G, there are typically thousands of SEPs (owned by multiple IP rights holders such as Ericsson, Qualcomm and Nokia) that work together to deliver the service and create value. In addition, downstream providers such as Apple, which implement the SEPs in their smartphones, also have their own patents (e.g. for designs of the phones used by the consumers) that contribute to the final value of the device (or the contract).

Whatever the setting, in assessing the pricing of IP, there is a need to ensure that IP-owners have the incentive to innovate further and hence create more economic value in future. At the same time, downstream players need to have the incentive to disseminate the innovation widely for the benefit of consumers, which increases still further the extent of its use and hence the economic value of the IP. This approach increases long-run consumer surplus, as the right balance ensures that each layer in the value chain makes sufficient profits to continue to create value in the form of variety and quality of content that is available to consumers at a reasonable price.

The value chain and value added in copyrighted music

The value chain for the consumption of music or audio-visual content is broadly composed of the following layers, each of which adds to the total economic value of the final product.

- Rights owners, who develop the content. This serves as the starting point of economic value, which is influenced (for example) by the quality of content created by the songwriter.

- Collecting societies, which bring together rights owners and rights users. In its position as the intermediary, a collecting society has to: (a) manage and maintain relationships with the rights owners—as failure to do so could lead to the withdrawal of rights by the rights owners; and (b) negotiate tariffs with as many rights users as possible for the licensing of the creative works within its repertoire. Where effective, collecting societies therefore facilitate better market functioning, for example by reducing search and transaction costs and exploiting the benefits of the network effects of their platforms.

- Rights users—i.e. commercial service providers such as digital platforms, physical distributors and retailers, which can, for example, enhance the value proposition to consumers by innovating in content delivery (for example, through online media distribution, or new content delivery formulas such as video on demand).

Methods of assessment

In principle, therefore, the question of whether a specific royalty rate is fair and reasonable should be assessed in relation to the contribution of each player in the value chain.

Direct method of assessing contribution

While a direct method of measuring contribution would be ideal, its feasibility depends on context. For example, it is likely to be very difficult to measure the contribution of a collecting society, because this would require a comparison of the current model with one in which each author manages their own rights and licenses directly to service providers (which at present is not a very common model).

In the context of SEPs, such a direct approach may be used, although it is no doubt a difficult exercise. It would involve two steps: (a) an assessment of the contribution of, say, 4G technology, to the final value of a smartphone to inform the total royalties that 4G SEP owners should receive (the rest of the final value would go to the implementers); and (b) allocating this total royalty amount among the various 4G SEP owners. This could be implemented using a range of methods. For instance, in step (a), a conjoint survey of consumers could assist in measuring the contribution of specific technologies or features of the phone in the final value to consumers,8 while the allocation of royalties in step (b) could be based on the number and value of patents in the portfolios of different SEP owners.9

Assessment of the bargaining process and impact on downstream competition

An alternative way to assess whether the distribution of economic value is ‘fair’ or ‘reasonable’ is to look at which outcomes allow the set of participants to obtain sufficient remuneration to make their long-term participation in the value chain a worthwhile economic activity (akin to the court’s approach in British Horseracing Board), and the process of reaching these outcomes.

To assess the process of ‘dividing the pie’, it is useful to think about a bargaining game, where the bargaining power and strategy of each party and the ultimate terms of the agreement are determined by several factors. These include:

- the attractiveness of the outside options that each party has in the event of a breakdown in negotiations, and its ability to credibly commit to these;

- the value that each party brings to the table;

- the information set that each party holds;

- the patience of each party to endure prolonged bargaining.

The box below illustrates the potential bargaining strategies of a service provider in a copyright context. The assessment of the strategies can inform the bargaining power of each side, and hence the assessment of fairness. For example, if a service provider of musical works is making high profits and is found to be engaging in ‘hold-out’ of royalties, and there is a low chance of an injunction, this may indicate that it has a high bargaining power and that there is a low likelihood that the collecting society can charge excessive or unfair royalties.

Potential bargaining strategies in copyright

In the bargaining game over the licensing of the rights managed by a collecting society, downstream service providers can, in principle, use a range of the following strategies.

- Stopping (or threatening to stop) making use of the rights within the collecting society’s catalogue. Whether such an action (or threat) will be practicable or credible depends on how essential the copyrighted material is for the proper functioning of a service provider’s business.

- Focusing (or threatening to focus) their catalogue on other content for which the collecting society does not own the rights. This would involve changing the rights usage to no longer rely on those rights provided by a particular collecting society, and instead using royalty-free works or even starting self-production.

- Seeking (or threatening to seek) direct licensing with rights owners, thereby by-passing the collecting society altogether—the feasibility of which depends on the transaction costs involved.

- Strategic ‘holding out’ of payment: despite exploiting rights within the repertoire of the collecting society, a rights user may opt to refuse or delay payment (usually referred to in the literature as ‘hold-out’ or ‘reverse hold-up’). This is because, in the case of IP, the rights holders (or patent owners) cannot easily prevent the use of the IP by downstream service providers, even if they do not pay royalties, as the information embodied in the IP is publicly available. IP owners can, however, take recourse to legal measures, such as injunctions, depending on the broader legal landscape in the jurisdiction in question.1

Note: 1 For a discussion of the economics literature on hold-up and hold-out in the context of SEPs, see, for example, Lemley, M.A. and Shapiro, C. (2007), ‘Patent Holdup and Royalty Stacking’, Texas Law Review, 85; Geradin, D., Layne-Farrar, A. and Padilla, J. (2007), ‘Royalty Stacking in High Tech Industries: separating myth from reality’, CEMFI Working Paper No. 0701; and Camesasca, P., Langus, G., Neven, D. and Treacy, P. (2013), ‘Injunctions for Standard-Essential Patents: Justice Is Not Blind’, Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 9:2, pp. 285–311. See also In the Matter of Certain Wireless Devices with 3G and/or 4G Capabilities and Components Thereof, United States International Trade Commission Investigation No. 337-TA-868, p. 114.

Comparators or benchmarks

Another common method to assess fairness of royalties is the use of comparators. This has been used in many past cases, and the judgments in Unwired Planet and AKKA/LAA have also confirmed it as a valid approach.

This method uses agreements in the same or similar market(s), and/or involving similar parties as benchmarks.

For example, in a royalty dispute between a collecting society and a specific service provider, a good comparator might be the agreements between the same collecting society and other service providers in the same market and country. If a similar royalty rate is widely accepted by other users, and they are thriving in the market, this would provide evidence that the rate is indeed fair and reasonable, and not excessive given the specific market context. The benchmarking could also involve a comparison of the disputed rate with that charged by collecting societies in other countries. An important factor in this comparison is the ‘comparability’ of the benchmark country (as it is with any benchmarking exercise). If there are likely to be systematic differences, it is important to account for these. This was discussed in depth by the CJEU in AKKA/LAA, where the court ruled that:

For the purposes of examining whether a copyright management organisation applies unfair prices…it is appropriate to compare its rates with those applicable in neighbouring Member States as well as with those applicable in other Member States adjusted in accordance with the PPP [purchasing power parity] index, provided that the reference Member States have been selected in accordance with objective, appropriate and verifiable criteria and that the comparisons are made on a consistent basis.10

The comparator approach was also relied on by the court in Unwired Planet in assessing whether the royalty offers were FRAND, and whether these offers could amount to excessive pricing.11

As to when a high price would amount to excessive pricing under competition rules, the above judgments provide some guidance. Specifically, the CJEU in AKAA/LAA clarified that, for a rate to be considered an abuse, the difference between the rate and comparators must be significant and persistent. It also noted that, even in such a case, it is possible for the rights owner to justify the differences based on objective reasons (which might include differences in administrative costs or quality).12 This case has been sent back to the Supreme Court of Latvia.

In Unwired Planet, the royalty offer for the relevant SEPs was found to be above FRAND. Notwithstanding that the judgment is on appeal, the court found that the offer(s) did not amount to excessive pricing under competition law, because (a) they were offers rather than a final price; (b) the offers were not so high as to hinder Huawei’s ability to make counteroffers and for the negotiation to proceed; and (c) the offers did not distort downstream competition.13

Concluding remarks

The recent excessive pricing cases in IP provide useful guidance on the various methods that can be used to assess royalty rates. While the appropriateness of the methods will vary depending on context, these cases support the use of the economic value approach à la British Horseracing Board and the use of comparators in assessing the price of IP. It remains to be seen what these cases imply for the threshold for a finding of excessive pricing in the presence of patents and copyrights.

1 It includes multiple cases in pharmaceuticals, musical works and telecommunications across Europe. See Oxera (2017), ‘Excessive pricing: excessively ignored in competition law?’, Agenda, July.

2 Unwired Planet International v Huawei Technologies, [2017] EWHC 711 (Pat), judgment of 5 April 2017. Oxera acted as experts for Unwired Planet in this matter.

3 CJEU, Case C-177/16, AKKA/LAA v Konkurences padome, judgment of 14 September 2017.

4 There are several other cases in these sectors. These include Nokia Technologies OY v Apple Inc and others, High Court of Justice, Case: HP-2016-000066; Apple Retail UK v Qualcomm, High Court of Justice Chancery Division, HP-2017-000015; and Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia (2015), ‘Resolución (S/0500/13 AGEDI/AIE RADIO)’, November. The pharmaceutical sector has also seen a number of excessive pricing investigations by various authorities. While IP plays an important role in this sector and influences the price of drugs, these cases have concerned the final prices to consumers/payers. In this article, we focus on the price of the IP itself.

5 Case 26/75 General Motors Continental NV v Commission [1975] ECR 1367, para. 12; Case 27/76 United Brands v Commission [1978] ECR 207; [1978] 1 CMLR 429, paras 250–2.

6 Scandlines Sverige AB v Port of Helsingborg (Case COMP/A.36.568/D3), Decision of 23 July 2004, para. 209; Attheraces v British Horseracing Board [2007] EWCA Civ 38, para. 218.

7 The court recognised that ‘this theoretical answer leaves the realistic possibility of a monopoly supplier not quite killing the goose that lays the golden eggs, but coming close to throttling her’. Attheraces v British Horseracing Board [2007] EWCA Civ 38, para. 217. See Oxera (2017), ‘Excessive pricing: excessively ignored in competition law?’, Agenda, July.

8 Conjoint analysis is a well-established method that is widely used in consumer research. It uses consumer surveys and statistical analysis to determine consumer preferences and willingness to pay for certain features relative to others in the same final product, in order to find the value of the relevant feature(s). Such analysis has been used in competition cases as well as in some patent cases (such as Oracle America, Inc. v. Google, Inc., No. C 10–03561, 2012 WL 850705, (N.D. Cal. Mar. 13, 2012); and TV Interactive Data Corp. v. Sony Corp., 929 F. Supp. 2d 1006, 1019–20 (N.D. Cal. 2013)). Although courts have not admitted such evidence in all cases, they have accepted the concept of using conjoint surveys, provided that they are well-structured and applied appropriately to the case at hand.

9 There are a range of metrics for this, including family size, patent renewals, the number of claims, and backward and forward citations.

10 CJEU, Case C-177/16, AKKA/LAA v Konkurences padome, judgment of 14 September 2017, para. 72(2).

11 Unwired Planet International v Huawei Technologies, [2017] EWHC 711 (Pat), judgment of 5 April 2017, paras 170–174.

12 CJEU, Case C-177/16, AKKA/LAA v Konkurences padome, judgment of 14 September 2017, paras 56–57.

13 Unwired Planet International v Huawei Technologies, [2017] EWHC 711 (Pat), judgment of 5 April 2017, paras 153 and 756–784.

Download

Contact

Dr Avantika Chowdhury

PartnerRelated

- Antitrust

- Commercial Litigation and International Arbitration

- Finance and Valuation

- Intellectual Property

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More