A guide to revising tariff structures

A vital aspect of the design of regulated markets is the definition of tariff structures. There are many influences on this, with potentially conflicting pressures, and as a result there is a wide range of potential outcomes. This article discusses both influences and outcomes and identifies factors to consider when revising a structure. It then considers some contemporary pressures that are forcing a reconsideration of existing tariff structures Finally, the article proposes a practical process for enacting change.

Why tariff structure is important

The effects of a tariff structure are felt far and wide.1 Not only will it affect the stability of the regulated company and the consumption behaviours of its customers, but it will also impact on adjacent markets, and wider society, especially as regards the costs and benefits of externalities. Moreover, there are many influences on tariff structure design, with potentially conflicting pressures that can lead to a wide range of potential outcomes, even in the same sector operating under common regulations intended to create a single efficient market. This is graphically illustrated for the case of rail track access charges (see Box 1).

Box 1 Disparity of tariffs in the case of rail track access charges

Rail access charging is governed by the Recast Directive (2012/34/EU) and the EU Regulation on infrastructure charges (215/909), intended to create an efficient single market. Despite the presence of a directive and a regulation intended to ensure uniformity of tariff setting principles in a single market, in it was observed:2

- In Germany, a principle of cost recovery was applied, but segments must comply with statutory obligations to avoid cross-subsidy between federal states.

- In France, the objective was also cost recovery but there is a wide range of mark-ups, especially on high-speed trains, to support policy objectives.

- In Sweden, tariffs were set on a marginal costing basis to promote economic efficiency, through recovery of maintenance and renewal costs, which are set through econometric analysis.

- In Britain, tariffs were also intended to reflect marginal costs, though wear and tear costs are set on an engineering basis that leads to lower estimates than an economic approach.

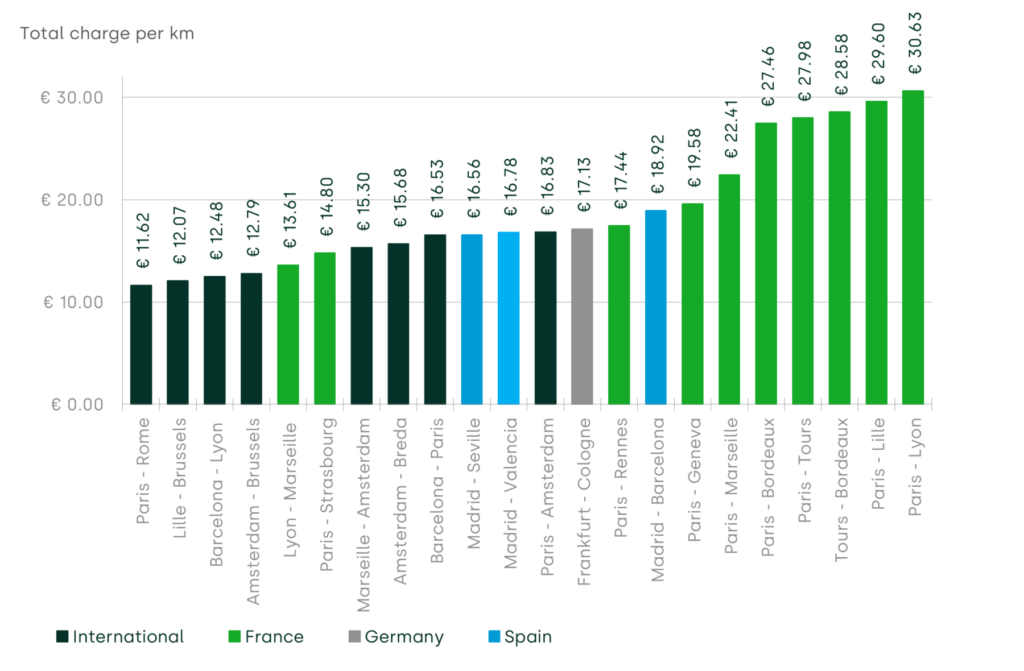

In practice, the constraints posed by the directive and regulation were not particularly constraining, as although they require the recovery of direct costs, they permitted a wide leeway for recovery of indirect costs, and the use of congestion charges and environmental levies (e.g. for noise). The regulations also permitted policy-driven mark-ups. Therefore, it is not surprising that there is a wide range of track access charges per km between origin/destination pairs. The figures for High-Speed Rail are shown in Figure 1, below, and appear to bear little relation to underlying costs (e.g. cost per km for Paris to Lyon is almost three times the rate of Paris to Rome). There are also consistent differences between national and international routes.

Figure 1 Track access charges per km (2017)

Principles for designing tariffs

Given the wide range of factors that influence tariff-setting and the consequent impact on the tariffs themselves, it would be useful to develop a set of principles to consider, before applying a process to revising tariffs. Bonbright (1961)3 4 and those listed below are similar, but the principles referenced here are adapted for contemporary European parties with a greater emphasis on social and environmental considerations, including demand management.

The following wide range of objectives are now relevant when designing tariffs:

| Efficiency | Encourage market efficiency, e.g. charging at marginal cost and recognising costs of externalities. |

| Recovering efficient costs of the existing network, including asset renewal to ensure resilience. | |

| Avoiding market distortions when there is competition with substitutes. | |

| Finance | Obtaining funds for the expansion of a network, to serve the future market. |

| Ensuring financial stability of the utility in the face of macroeconomic or supply shocks. | |

| Demand | Adjusting demand profiles to avoid peaks that lead to unused capacity during quiet periods. |

| Growing demand and fostering economic growth, if sustainable. | |

| Social | Discouraging unnecessary demand and waste, if necessary, to promote sustainability. |

| Promoting social equity and protecting the vulnerable who may struggle to pay. | |

| Providing a universal service to the whole population at an affordable price. | |

| Practicality | Keeping data collection requirements to a practicable level, e.g. on usage and timing. |

| Producing a simple tariff structure that the consumers can understand and which is perceived as ‘fair’.5 |

Many of the above principles rely on the principle of ‘cost reflexivity’, which may be a statutory requirement, and even if not, customers are generally more willing to accept a charge that is related to the cost of providing a service. However, infrastructure networks share many costs across services and customers, and this immediately leads to a question of how those shared costs will be allocated. An authoritative text for cost allocation was provided by Oxera for the former Office of Fair Trading.6

It is also apparent that some objectives are potentially contradictory, e.g. whether to grow or reduce demand. The issues around demand management are discussed in more detail below.

Demand management of peaks

Peaky demand is the enemy of supply chain efficiency—it leads to the need for local storage, if practicable, or excess capacity to service peak demand, if not. The use of tariffs to reduce the peak is commonplace, e.g. off-peak train fares and electricity tariffs. If there is a need to demonstrate cost reflexivity, then consumers can be charged in proportion of capacity used, with a premium charge for capacity used at ‘critical peaks’, when simultaneous demand places maximum strain on the system. Options include Peak Demand tariffs (based on the consumer’s individual peak demand in a period), or Time-of-Use tariffs that reflect the peak demands of the whole system (this is simpler for the consumer to monitor).

Price discrimination to increase demand

Price discrimination, if pro-competitive, is not only legal but widely practiced, to attract new customers, increase volume and hence recover fixed costs. It is typically divided into three degrees: the first degree aims to appropriate consumer surplus by individual pricing for consumers (becoming more feasible with the advent of algorithmic pricing7); the second degree that prices through special offers, e.g. quantity discounts; and the third degree that discriminates by targeting demographics, e.g. elderly customers or students being offered discounted train fares. The tariff structure may seek to level demand and grow demand simultaneously, and enhance social equity by allowing the participation of disadvantaged groups.

An example of aiming for demand growth is the introduction of flat tariffs, discussed in Box 2.

Box 2 How tariffs can make a difference

There have been recent cases where dramatic changes in consumer tariffs have been enacted in pursuit of policy objectives. One such example is the flat-fare tariff for public transport.

In Germany, the Deutschland Ticket (D-Ticket) has been introduced that allows for use of all means of local public transport (but not inter-city) for just 49 euros per month. This is intended to address multiple policy objectives, including sustainable travel and the cost-of-living crisis, and follows similar schemes introduced during the Covid epidemic.

A similar but not identical concept applies to English busses. For the remainder of 2024, the £2 fare cap for a single journey will apply. This is an extension of a previous scheme, and Monitoring and Evaluation reports8 show increased bus usage and a positive impact on the cost of living, thus providing a robust link between a tariff change and a change in behaviour.

Declining demand

Tariff structures may also require modification in the light of falling demand. For example, this could apply in the following circumstances.

- In postal services, where there is the universal service obligation that necessitates the maintenance of a network whose nodes have increasing unused capacity and whose fixed costs would make the service unaffordable, if priced on a cost-reflective basis.

- In gas distribution, where forecast declining volume raises the question of how the cost of the assets in the regulatory asset base will be recovered; this can also lead to a negative reinforcement effect whereby a reduction in demand could lead to higher prices, which in turn, further reduce demand.

In these circumstances, conflicting objectives apply to setting tariffs and a key consideration is often to maintain the financial stability of the infrastructure provider in the face of falling demand, thus continuing an essential service to remaining users.

Non-linear tariffs

Volumetric tariffs may be constant with volume, or they may rise or fall, with increasing volumes. Perhaps the most extreme example of a falling tariff is the retail Buy One Get One Free (BOGOF) deal, where the marginal cost of the second item to the customer is zero; however, there are less extreme forms of incentives to increase volume and design of incentives using discounts is a key aspect of sales and marketing. In many cases, reduced prices for increased volume will also be cost reflective as average cost can fall with increased volume, if there are fixed costs in supply of goods and services.

However, in some regulated sectors, such as water, where conservation is an issue, there is also an interest in Increasing (or Rising) Block Tariffs (IBTs), to provide disincentives for high consumption.9 In the UK, IBTs have been trialled but limited IBT trials in the UK did not yield promisingoutcomes’.10 Nonetheless, several other trials are underway or are planned.11 Internationally, ‘experience of IBTs from the US, Spain and Australia suggests mixed evidence regarding the effectiveness of IBTs’. 12 In summary, IBTs may have a contribution to make to conservation, though their success is not assured, and non-price interventions (discussed in the next section) should also be considered.

Apart from IBTs, there are other price interventions that can assist small-volume consumers who may struggle to pay—for example, the elimination of the standing charge. One instance of this can be found in Ireland, where water is free up to a certain threshold (deemed to represent essential water) and costs are recovered through a volumetric charge only.13

Social tariffs

It is recognised that some tariffs that are intended to help the disadvantaged, such as the elimination of the standing charge and the use of IBTs, can have unintended impacts on some households, e.g. those with a large number of dependents. For this reason, an alternative approach is a ‘social tariff’ aimed at those in receipt of certain welfare benefits. The behavioural implications also need to be considered, especially as regards the disincentives for coming off welfare benefits if too many additional benefits are tied to it. However, recent research on the cost-of-living crisis was revealed by Oxera as part of its ‘Great Squeeze’ study14, and there may be a case for extending social tariffs beyond those claiming benefits.

Behavioural economics

Non-price interventions can be effective, e.g. providing information on consumption can modify behaviour. Moreover, some very minor tariffs can be used to induce major changes; for example, in the UK, the introduction of a minor plastic bag charge in supermarkets led to a 98% reduction in use.15 This is an example of a ‘nudge’, which is a means of inducing a voluntary change in behaviour through an understanding of consumer psychology.

Another example of nudge is the use of an ‘anchor’. A customer may be offered a low or a medium price option, and opt for a low option; however, if a premium price offer is introduced, this acts as the ‘anchor’ in their mind and, subsequently, their interest switches to the medium price option. An alternative approach is to exploit the tendency for consumers to opt for a default option, so revenue can be increased by making the higher price option the default, with an option to downgrade, compared to the reverse of being offered an upgrade from a lower price.

Nudges are applicable to regulated sectors and an overview of the topic with examples from the financial services sector is available in Oxera’s publication ‘Understanding and influencing behaviour: economics vs science’16 and, in energy markets, ’Summoning the energy: consumers and competition’17; further details are available in the Behavioral Economics Guide 2022.18 Other recent research, however, questions the effectiveness of nudges.19

Shrouding

Less ethically, and a practice best avoided, is also the behavioural malpractice of obfuscation where firms design tariff structures that are difficult to compare to lower the intensity of competition and hence boost profitability, creating a ‘shrouded economy’.20 Regulators are keenly aware of the problem, but a lack of clarity can exist in tariff structures in fields that are as diverse as financial services,21 mobile phones,22 and rail and air fares.

Another confusing tactic is to use add-on fees—a ‘salami tactic’. The consumer is enticed with a low base price but is then presented with add-on fees during the selling process; airlines are adept at this, charging additional fees for choosing a seat, or checking baggage that customers may have assumed were included in the additional price; to counter this, in the UK, the sector regulator attempts to inform customers by publishing comparison tables.23

Rate setting process

Once objectives have been clarified and a potential tariff structure (with alternative options) is designed, there remains the process of introducing the new structure to the market. The following process provides a structured approach.

- Review regulatory and legal constraints, to confirm that the potential structures are compliant.

- Begin a consultation process with current and future customers, and other stakeholders.

- Review experience of charging models from comparable sectors.

- Summarise pricing options in a position statement, to seek stakeholder feedback.

- Analyse organisational costs and drivers, to forecast costs, including impact of volume changes.

- Research future demand forecasts and price elasticities of demand.

- Forecast impact of pricing options on finance-ability of the organisation.

- Recommend a preferred tariff option and calculate the new tariffs.

- Obtain approval for the change, if necessary.

- Develop a communication programme to explain the need and principles of the new tariffs.

- Develop a programme plan for transition and define a project management structure.

- Create steering groups to guide and monitor the change management process.

This process stresses the consultative aspect of changing tariffs. Even if not a legal requirement, there will be a benefit in bringing customers along and communicating the benefits from their own point of view.

Conclusion

Changing circumstances, ranging from the sustainability imperative to the cost-of-living crisis, are forcing the need to revise many tariff structures. This article has highlighted the issue of conflicting objectives when setting new tariffs, alongside the wide array of options to respond to those objectives. When reviewing tariffs, it is important to undertake a consultative process, not least to explain to customers the intentions behind the new tariffs.

1 A tariff structure will typically comprise a fixed time-based charge, a volumetric rate that itself may vary with volume, time or season, and additional adjustments, e.g. social to account for low-income households.

2 Centre on Regulation in Europe (2018) ‘Track access charges: reconciling conflicting objectives’, 9 May.

3 Bonbright, J.C. (1961), Principles of Public Utility Rates, Columbia University Press.

4 Bonbright proposed the following: (i) Rate attributes: simplicity, understandability, public acceptability, and feasibility of application and interpretation (ii) Effectiveness of yielding total revenue requirements (iii) Revenue (and cash flow) stability from year to year (iv) Stability of rates themselves, minimal unexpected changes that are seriously adverse to existing customers (v) Fairness in apportioning cost of service among different consumers (vi) Avoidance of undue discrimination (vii) Efficiency, promoting efficient use of energy and competing products and services products and services.

5 The concept of fairness in tariffs was discussed in Oxera (2019) ‘Fair ground: a practical framework for assessing fairness’, March.

6 Office of Fair Trading (2003) ‘Assessing profitability in competition policy analysis. Economic Discussion Paper 6. July 2003. A report prepared for the Office of Fair Trading by OXERA.’, July. Available from www.oxera.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/OFT-Assessing-profitability-1.pdf.

7 Shiller, B.R. (2013).’First-Degree Price Discrimination Using Big Data’. Brandeis University, Department of Economics.

8 See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/evaluation-of-the-2-bus-fare-cap/2-bus-fare-cap-evaluation-interim-report-february-2023.

9 Whittington, D. and Nauges, C., (2020), ‘An Assessment of the Widespread Use of Increasing Block Tariffs in the Municipal Water Supply Sector’, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Global Public Health.

10 Center for Competition Research (2018), ‘Price and Behavioural Signals to Encourage Water Conservation’, July (p. v). Available from www.ofwat.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/20221102-_ANH_UEA_CCP-report-_Price_and_Behavioural_Signals_to_Encourage_Water_Conservation.pdf.

11 See https://www.ofwat.gov.uk/regulated-companies/company-obligations/ofwat-regulating-the-industry-compliance-requirements-charging/household-charging-trials/#current.

12 Center for Competition Research (2018), ‘Price and Behavioural Signals to Encourage Water Conservation’, July (p. iii). Available from www.ofwat.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/20221102-_ANH_UEA_CCP-report-_Price_and_Behavioural_Signals_to_Encourage_Water_Conservation.pdf.

13 See https://www.water.ie/help/domestic-account/household-conservation-charge/.

14 Oxera (2023), ’The Great Squeeze’, Agenda, May.

15 See https://www.gov.uk/government/news/plastic-bag-use-falls-by-more-than-98-after-charge-introduction

16 Oxera (2023), ’Understanding and influencing behaviour: economics vs science’, Agenda, May.

17 Oxera (2016), ’Summoning the energy: consumers and competition’, December.

18 Samson, A. (Ed.) (2022), The Behavioral Economics Guide 2022. Accessible from https://www.behavioraleconomics.com/be-guide/the-behavioral-economics-guide-2022/ .

19 Maier, M., Bartoš, F., Stanley, T.D., Shanks, D.R., Harris, A.J. and Wagenmakers, E.J., (2022), ’No evidence for nudging after adjusting for publication bias’ Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119:31, p. e2200300119.

20 Halpern, D., Makinson, L., Costa, E., Szreter, B. and Broughton, N. (2024) ’The Shrouded Economy’, March. Accessible from www.bi.team/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Shrouded-Economy-Working-Paper.pdf.

21 Agarwal, S., Song, C. and Yao, V. (2022), ’Banking Competition and Shrouded Attributes: Evidence from the US Mortgage Market’. Accessible from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2900287.

22 Oxera (2016), ’Please leave a message: has telecoms become too complex for cosnumers’, Agenda, August.

23 See www.caa.co.uk/media/mu0dbn4j/airline-charges-2023.pdf.

Contact

Dr Rupert Booth

Senior AdviserRelated

- Energy

- Financial Services

- Postal and Logistics

- Retail and Consumer

- Telecoms, Media and Technology

- Transport

- Water

Related

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More