Adaptive planning for pathways through uncertainty: from theory to practice

Traditional methods of infrastructure planning, based on the concept of ‘predict and provide’, are becoming less useful as the level of uncertainty about the future increases. New methods are being developed that emphasise adaptability, and keeping options open. What do these methods involve, and how might they be applied in the UK water sector? What challenges arise in terms of both analytical capacity and stakeholder management?

‘Prediction is very difficult, especially if it’s about the future’ is a Danish joke attributed to Niels Bohr, Nobel laureate and father of quantum mechanics. Now, prediction is even more difficult, given a rise in uncertainty that is in large part caused by climate change. This is a problem for infrastructure provision, which in the past has generally followed a ‘predict and provide’ principle against a fairly predictable backdrop. It is now recognised that this principle faces a fundamental difficulty—namely, increasing uncertainty making predictions less reliable.1This may arise due to the provision of the infrastructure itself affecting the prediction (as is the case with the issue of induced demand for transport), or the impact of external factors, such as climate change or epidemics. These are best described as ‘grey swans’—events that are to be expected, but whose timing and magnitude cannot be predicted.

The need for a new approach for infrastructure appraisals has not gone unnoticed in government guidance or regulatory approaches. The UK Department for Transport (DfT) has recently released an ‘uncertainty toolkit’ to assist in the analysis of risk and uncertainty in investment appraisals.2 Most of the toolkit arranges well-established methods in a unifying format, but the toolkit also mentions ‘other decision-making approaches’ for analysing ‘deep uncertainty’. It states that these techniques are likely to be appropriate when the contextual uncertainties are major, the policy framework has many degrees of freedom, and system complexity means it is difficult to link policies.

Delving into ‘deep uncertainty’

Before describing these approaches, it is useful to further clarify the meaning of ‘deep uncertainty’. This has been defined as a situation:3

…where analysts do not know, or the parties to a decision cannot agree on, (1) the appropriate conceptual models that describe the relationships among the key driving forces that will shape the long-term future, (2) the probability distributions used to represent uncertainty about key variables and parameters in the mathematical representations of these conceptual models, and/or (3) how to value the desirability of alternative outcomes. In particular, the long-term future may be dominated by factors that are very different from the current drivers and hard to imagine based on today’s experiences.

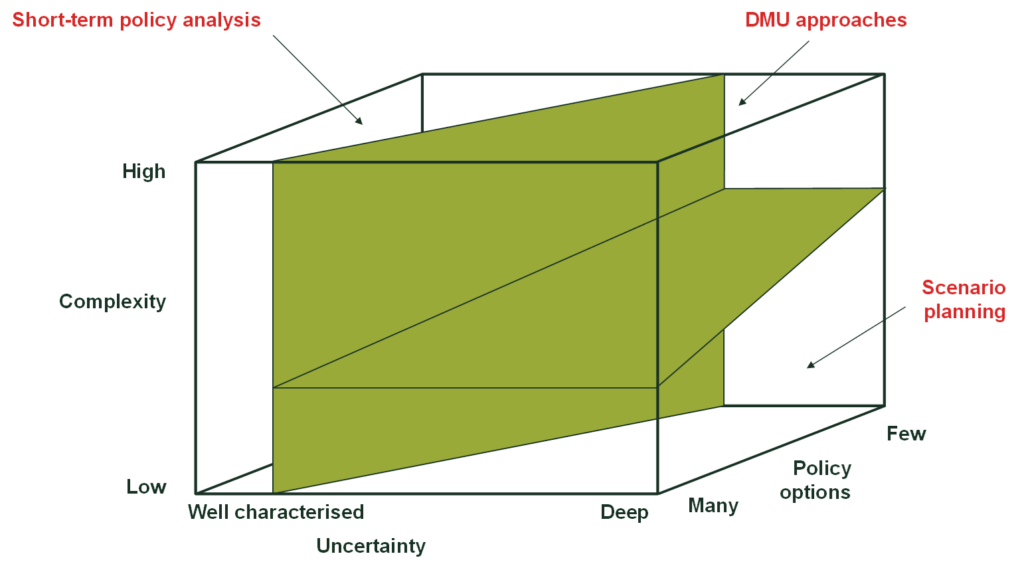

The second point is especially relevant in an era when non-normal probability distributions with ‘fat tails’ are increasingly observed, with a greater than expected probability of extreme values than in a normal distribution. Marchau et al. (2019) covers several approaches to decision-making in more detail, and provides case studies of their use.4 However, which of the range of tools in this toolkit should be used? Figure 1 provides a guide put forward by the authors, and identifies three critical dimensions: the degree of uncertainty, the level of complexity, and the number of policy options.

Figure 1 Decision-making under uncertainty

For well-characterised uncertainty, and medium uncertainty with few policy options, the authors note that the traditional ‘predict and provide’ approach is appropriate—for example, this might involve Sensitivity Analysis and Monte Carlo Analysis. However, in the ‘deep uncertainty’ environment, ‘Scenario Planning’ should be deployed where there is low complexity with many options, or medium complexity with few options. In these cases, ‘Scenario Planning’ can be supported by expert intuition.

A summary of the ‘Scenario Planning’ process is given in Lyons et al. (2021), which also includes case material from New Zealand and Scotland. It provides advice on scenario development by answering ten commonly posed questions, namely:5

What is a scenario? Why or when are scenarios worth developing? Who should be involved in developing scenarios, how and why? How is the scope of a set of scenarios clarified? Do scenarios have to be tailored to a particular application? How far should the bounds of future possibility be stretched? How many variables are needed and how many scenarios? How are the scenarios developed? How is a scenario brought to life? How much time and effort are needed for scenario development?

While the Lyons et al. paper is focused on transport, its content is equally applicable to any sector facing uncertainty, especially those considering adaptation to climate change, such as water and energy.

In the remaining cases shown in Figure 1, including ‘deep uncertainty’ with high complexity and many policy options, the authors propose that DMDU approaches should be used. However, a recent and comprehensive literature review of these approaches by Stanton and Roelich (2021) found only 37 case studies, 80% of which were ‘could do’ studies rather than reports of actual application.6 Of the 37 case studies for infrastructure studies, 76% were in the water sector, and 16% in transport. Regarding the methods, 53% of cases used Robust Decision Making (RDM) and 44% used variants of the approaches based on adaptive pathways.7

How do the multiple approaches differ?

RDM was developed by the RAND corporation and considers how one can make good decisions without first needing to make predictions.8 RDM comprises the following iterative process that may follow on from an earlier scenario analysis exercise.

- Decision Framing, where stakeholders work towards a shared understanding of the problem to be solved. A key facet is the XLRM matrix of Uncertainties (X), Policy Levers (L), Relationship Models (R) and Performance Metrics (M).

- Evaluate Strategies Across Futures, an analytical step of running a model over many possible futures, to calculate the key performance metrics for each.

- Vulnerability Analysis, which considers the set of uncertain conditions that causes a strategy to miss its goals.

- Trade-off Analysis, a deliberative stage where the trade-offs between strategies are discussed, such as cost versus performance metrics.

The process then iterates and considers new futures and strategies, until it concludes with robust strategies and scenarios that are relevant to the decisions being contemplated.

RDM will not, however, provide a pathway for future investments, contingent on future uncertainties. This is provided by the methods that are based on adaptive pathways. Although there is variation in how these methods are applied, a common theme noted by Werners et al. (2021) is that they ‘are broadly understood as sequences of actions, which can be implemented progressively, depending on future dynamics’.9 One variant that seeks to combine ‘adaptive policy making’ and ‘adaptation pathways’ is the ‘Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways’ (DAPP) approach, proposed by Haasnoot et al. (2013).10 Ramm et al. (2018) suggest combining the RDM and DAPP approaches to understand a problem and then develop an adaptable solution.11

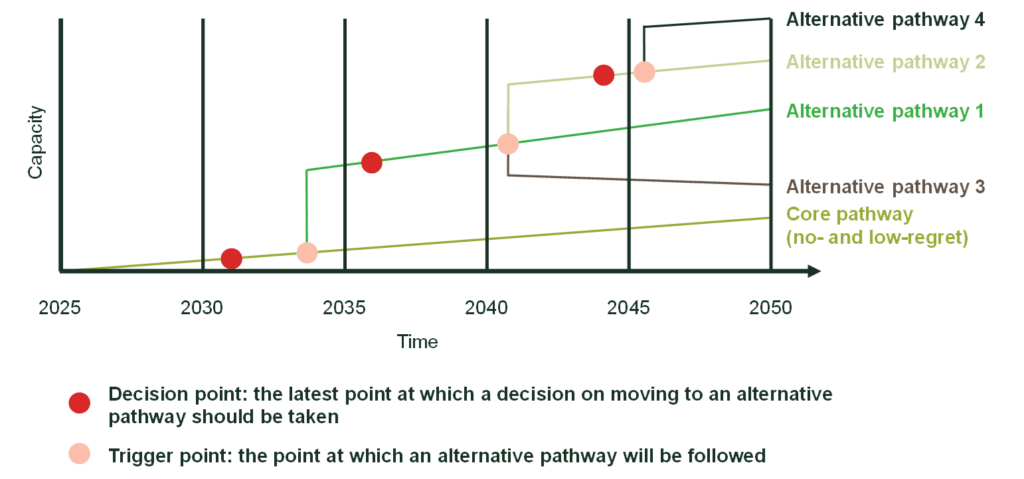

Interestingly, DAPP is similar to the approach proposed by Ofwat, the economic regulator of the water industry in England and Wales, which it calls ‘Adaptive Planning’, and which also extends to defining investment pathways.12 In setting out what Ofwat expects from water company business plans as part of PR24, the regulator has stated that ‘Adaptive Planning should be at the heart of the long-term delivery strategy’ and that ‘adaptive pathways set out how decisions will be made under different plausible circumstances’. Crucially, according to Ofwat ‘the strategy should present a core adaptive pathway of enhancement activities. It should then set out alternative adaptive pathways which could be triggered depending on how future uncertainties develop’. Ofwat’s proposed approach is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Adaptive planning in the water sector

In Figure 2, the ‘core pathway’ does not simply reflect a central scenario. It should include the no- and low-regret investments that are needed in a range of plausible positive and negative scenarios, and investments that are required to keep future options open.

To identify the potential for triggering, it is necessary to undertake scenario analysis and to ensure some consistency. Ofwat has set up reference scenarios in terms of climate change, technology, demand, and water abstraction, as well as permitting a category of company-specific factors. The reference scenarios are intended to represent ‘plausible extremes’.

What is feasible in practice?

The fly in the ointment is that the analytical workload required to undertake adaptive planning is considerable. Not only is extensive scenario analysis essential, but a set of pathways (core and alternative) must also be defined to respond to the scenarios. These pathways comprise investments that reflect customer expectations and meet regulatory requirements. Furthermore, the triggering criteria must be defined.

Defining this decision support framework is likely to involve Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis,13 and the financial analysis of options is likely to involve Real Options theory.14 Furthermore, the data requirements are onerous; there is a need to model the impacts of the different scenarios in order to choose appropriate alternative pathways.

Quite apart from these technical challenges, there is the issue of retaining stakeholder engagement when discussing a range of distant future hypothetical events. Many infrastructure planners are all too aware of the hostile reactions that can arise from planning a rational response to a single, near-certain, short-term scenario.

Whatever the difficulties, the days of predict and provide are over. The name of the game is now adaptability (or ‘flexibility’ and ‘agility’, to use alternative terms), and keeping options open for an uncertain future. The imminent use of Adaptive Planning approaches for infrastructure planning in the water sector will advance the science for the benefit of other infrastructure sectors, and public policy in general.

1 Kristalina Georgieva, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has stated: ‘If I had to identify a theme at the outset of the decade it would be increasing uncertainty’ (17 January 2020). In response, the IMF has produced a World Uncertainty Index. See Ahir, H., Bloom, N. and Furceri, D. (2020), ‘60 years of uncertainty’, International Monetary Fund, March (last accessed 26 October 2022).

2 Department for Transport (2022), ‘TAG: uncertainty toolkit’ (last accessed 26 October 2022).

3 Lempert, R., Popper, S. and Banks, S. (eds) (2003), Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative, Long Term Policy Analysis, RAND.

4 Marchau, V.A.W.J., Walker, W.E., Bloemen, P.J.T.M. and Popper, S.W. (eds) (2019), Decision Making under Deep Uncertainty: From Theory to Practice, Springer Nature (last accessed 24 October 2022).

5 Lyons, G., Rohr, C., Smith, A., Rothnie, A. and Curry, A. (2021), ‘Scenario planning for transport practitioners’, Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives, 11, September.

6 Stanton, M.C.B. and Roelich, K. (2021), ‘Decision making under deep uncertainties: A review of the applicability of methods in practice’, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 171.

7 The variants include Adaptation Pathways (26%), Dynamic Adaptive Planning (13%) and Dynamic Adaptive Policy Pathways (5%).

8 Lempert, R.J., Popper, S.W. and Bankes, S.C. (2003), Shaping the Next One Hundred Years: New Methods for Quantitative, Long-Term Policy Analysis, RAND (last accessed 26 October 2022).

9 Werners, S.E., Wise, R.M., Butler, J.R., Totin, E. and Vincent, K. (2021), ‘Adaptation pathways: A review of approaches and a learning framework’, Environmental Science and Policy, 116, pp. 266–75.

10 Haasnoot, M., Kwakkel, J.H., Walker, W.E. and ter Maat, J. (2013), ‘Dynamic adaptive policy pathways: a method for crafting robust decisions for a deeply uncertain world’, Global Environmental Change, 23:2, pp. 485–98.

11 Ramm, T.D., Watson, C.S. and White, C.J. (2018), ‘Strategic adaptation pathway planning to manage sea-level rise and changing coastal flood risk’, Environmental Science and Policy, 87, pp. 92–101.

12 Ofwat (2022), ‘PR24 and beyond: Final guidance on long-term delivery strategies’, April.

13 A decision-making approach that takes into account multiple factors.

14 Real Options theory applies the theory of financial options to tangible investments in the ‘real world’.

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More