Allocation of indirect costs

There is no right or wrong way to allocate indirect costs, only good or bad ways of supporting policy objectives, either of the company itself or an industry regulator or competition authority. This article reviews the many allocation options, before proposing a process for selecting the most promising option to meet the mix of objectives that apply in a particular situation.

Introduction

The recent Competition Appeal Tribunal verdict in favour of BT,1 which dismissed a £1.3bn claim for excessive and abusive pricing, is a reminder of the importance of the issue of cost allocation, one of the major issues of contention in the case. In this article, we take a broad view of indirect2 cost allocation, and consider the wide range of stakeholders that have an interest—so wide it is unlikely that a single set of principles could ever satisfy them all. These stakeholders include shareholders, taxation and competition authorities, economic regulators, customers and, not least, the corporate management. Each of these stakeholders will have different information needs, and we begin by considering the basic statutory requirements for accounts, which also provide a reliable source of historical data on fully allocated costs (FAC).3

Accounting standards

The simplest case is a single domestic company that needs to prepare annual accounts. These accounts support two main purposes—namely, calculating the tax due and providing shareholders with a fair valuation. For shareholders, there is a need to avoid overvaluation of inventory by including overheads unrelated to the cost of production, and for depreciation profiles to reflect the useful life of assets. The relevant International Accounting Standards (IAS) are IAS 24 ‘Inventories’ and IAS 165 ‘Property, Plant and Equipment’. IAS 2 requires that the allocation of indirect costs is done on a ‘rational and consistent basis’. IAS 16 determines how changes in asset value are recognised as costs, to be subsequently allocated via depreciation charges.

Matters become more complicated for a multinational corporation. Cost allocation can be used to shift profitability between jurisdictions—for example, towards a low taxation jurisdiction. National tax authorities are well aware of this, and hence take a keen interest in the calculation of transfer prices—which should be set at an arm’s length price, if possible—as well as prices and the allocation of intragroup charges. Regarding the latter, the OECD guidelines6 require confirmation that a service has been delivered, and that the basis for allocation is ‘an appropriate measure of the usage of the service that is also easy to verify’; an example is provided of payroll cost being allocated according to number of staff, i.e. recognising the principle of causality. Although transfer pricing and intragroup charging can be complex, the allocation of indirect costs is usually a matter of divisional accounting.

Product costing

The examples so far have involved the calculation of FAC in cases where the implications of the distortions of over-estimating the costs of some products, and under-estimating others, may not be that serious, provided that the aggregate figure is broadly correct. However, this is not the case once costs are used to support pricing decisions. In regulated sectors ‘cost reflective pricing’ or ‘cost orientation’ can be an explicit requirement. Even if there is no such requirement, then setting prices below a cost threshold may lead to a legal claim of ‘predatory pricing’, and setting prices far above FAC can lead to claims of ‘excessive pricing’.7 Therefore the allocation of substantial indirect costs to individual products and services is of paramount importance.

Given the often explicit need for cost orientation, it is hardly surprising that regulators are drawn to activity-based costing (ABC), which aims to allocate on the basis of causality. Some regulators fit ABC into a hierarchy of preference—for instance, the UK’s Payment System Regulator (PSR) requires,8 in Article 4, the following.

- Expenses that are directly attributable shall be allocated to the relevant activity.

- Expenses that are not directly attributable, i.e. are indirect, shall be allocated using ABC.

- Expenses that cannot be allocated using ABC shall be allocated according to an alternative method with a supporting explanation.

On the last point, some indirect costs cannot be allocated by ABC (see Box 1, below) and the simplest alternative method is equi-proportional mark-up (EPMU), where indirect costs are allocated in proportion to direct costs. However, there are many alternative allocation approaches, as explained below, and no single approach can be regarded as uniquely correct.

Box 1 Common and joint costs (CJCs)

A distinction should be drawn between common costs and joint costs, which is often not made and some sources even use the terms interchangeably or describe all non-incremental costs as ‘common’. To clarify, non-incremental costs, which may comprise the majority of costs, are of two types. Common costs occur where activities are combined together out of choice, usually to obtain economies of scale. This is typical in administrative activities where a single service centre will serve multiple customers with multiple services. It is possible to disaggregate common costs using ABC given sufficient effort (e.g. timesheets) and clarity on the relation between an activity and the support of a product and service, though in practice the latter may be obscure, so an alternative non-causal method may be used. Joint costs arise from a production or operational process producing products or services in tandem; the creation of the multiple outputs is inseparable and often in fixed proportions.9 An example from the energy sector is the production of oil and gas from a well—the joint costs between them cannot be allocated by considering cost causality and ABC. Instead there must be a view of the downstream prices, margins or price elasticities of the multiple products.

Source: Oxera

Incrementality

Regulators and competition authorities also have a particular interest in long-run incremental costs (LRIC) when setting prices or assessing pricing policies because it leads to allocative efficiency in markets.10 It is important to note that ABC, in itself, does not provide insight into cost variability11 or incrementality, though by clarifying cost causality at a disaggregated level, it may assist. This can be useful if there is a wish to adapt the ABC system to estimate LRIC costs on a top-down basis, as explained in the first Agenda article in this series, Blending Incremental Costing in Activity-Based Costing Systems.12

Often however, companies, especially in the telecommunications sector, build separate bottom-up LRIC models based on the cost–volume relationships (CVRs) of business processes to estimate the LRIC of products, typically on a forward-looking basis.13 This exercise also reveals the presence of CJCs that remain even when an increment is removed, to be allocated to products to support cost-orientated pricing.

Another relevant cost parameter for pricing purposes is the stand-alone cost (SAC) of a product, which is the cost of providing an increment in isolation and therefore includes all relevant common costs. SAC has its origins in the theory of contestable markets,14 which postulates that if prices were set above SAC and there were no barriers to entry, it would attract new entrants into the market and would not be sustainable as a result.

The two parameters, LRIC and SAC, allow for a range of allocation of indirect costs to support pricing, with the lower bound being set at pure LRIC,15 and the upper bound at SAC, to ensure that no product is being subsidised with a cost allocation lower than is incurred in production, and that no product is penalised by being allocated cost greater than if it was made in isolation. While this is a basis for implementing cost-oriented pricing, an issue that arises is that the range between pure LRIC and SAC can be broad, especially where there are significant CJCs such as in multiproduct network industries. Consequently, if all products are priced at LRIC, the firm would not be able to recover its CJCs, and prices could be viewed as ‘too low’; conversely, if all products are priced at SAC, the firm would over-recover its CJCs, and prices could be considered as ‘too high’.

One way of assessing whether a particular price might be regarded as being ‘too low’ or ‘too high’, is to consider whether the prices for different combinations of products lie between their LRIC and SAC. Where all the different combinations satisfy this test, there is no under- or over-recovery of common costs. This is the so-called combinatorial testing approach that is consistent with the theory of contestable markets. Despite issues of practicality—for example, in situations where the firm offers a particularly large number of products—this is an approach that could be feasible to implement, and one that is entirely appropriate.16

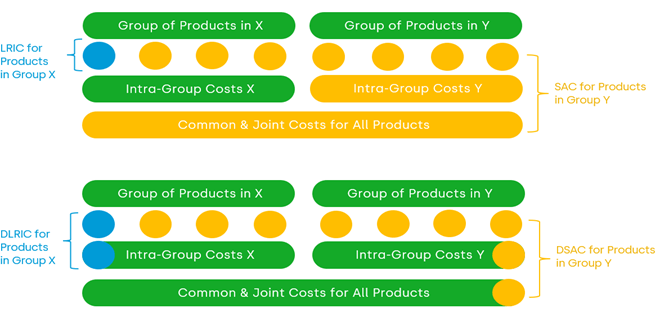

Another response developed in telecommunications has been to narrow the range by considering large increments of project groups, as shown in Figure 1 below. This approach defines a ‘distributed LRIC’ (DLRIC) and a ‘distributed SAC’ (DSAC) and reflects the inclusion of the CJC of intra-group activity that would be considered fixed for a single product.

Figure 1 Calculation of DLRIC and DSAC

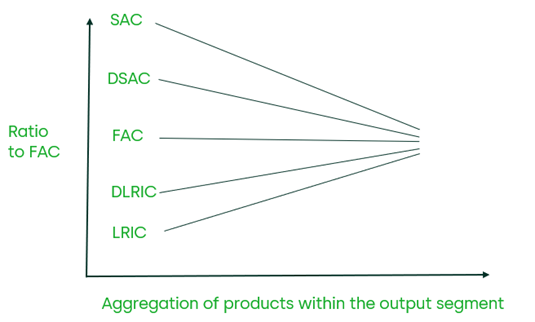

The effect of enlarging the increment is shown in Figure 2, below. It can be seen for increments that approach the size of the product portfolio of the firm—the distributed parameters approximate to FAC.

Figure 2 Convergence to FAC

However, there is still a need to identify systematic basis for product cost allocation (within the range of DLRIC and DSAC) and the chosen basis is commonly EPMU due to its simplicity, but other allocation methods could also be used. The product costs can then be compared to confirm cost-orientation. A degree of flexibility in pricing is often permitted and this can have some advantages for the price-setter and the DLRIC and DSAC bounds need not be the final word.17 Below, under ‘Alternative approaches’, we consider various allocation methods that draw upon a range of disciplines, including economics and game theory.

Short-run average costs

In addition to the LRIC discussed above, competition authorities and tribunals have also shown an interest in a set of related short-run average costs, because these are simple to calculate in the absence of an LRIC costing system. In terms of decreasing magnitude, these are:

- average total cost (ATC), that is the FAC divided by Quantity;

- average avoidable cost (AAC), namely the cost that would be avoided immediately if a product were stopped, divided by Quantity;

- average variable cost (AVC), namely the short-run variable cost divided by Quantity.

Relating these to LRICs is not straightforward, though an LRIC averaged across a segment (sometimes called a long-run average incremental cost, i.e. LRAIC) is usually higher than AAC, as it includes the long-term costs as well as the short, and will be lower than ATC.

Peak costing and bottlenecks

A further complication is that some supply chains have to satisfy peak demands, or premium products that use additional or out-of-hours capacity. This incurs additional indirect cost, which needs to be traced to the products requiring the premium service. An example is first class post.

Additionally, some supply chains have bottlenecks, and the use of the bottleneck capacity precludes alternative uses that may generate a financial contribution, i.e. there is an opportunity cost with their use. This can be reflected in a surcharge being applied to products using this scarce resource. This principle has been accepted in access pricing for rail infrastructure.

Alternative approaches

We now consider alternative approaches to EPMU, which works by simply marking-up the direct cost to account for the indirect CJC, without any further consideration of cost dynamics. For economists, there is the attraction of Ramsey pricing,18 where costs are allocated according to the inverse of the price elasticity of demand (PED), essentially loading a higher proportion of the CJC onto products with more inelastic demands. While this can be shown to maximise social welfare (the sum of producer and consumer surplus) and support allocative efficiency, it can in some situations be perceived as inequitable and therefore politically toxic. Moreover, there is the practical issue of estimating the PED for the various products.

It is important not to underestimate the appeal of ‘fairness’ in cost allocation. Efforts to clarify this subjective concept have been made—for example, by developing axioms for fairness, and defining a set of conditions that any proposed allocation must meet to be considered fair. One such set of conditions are the Core conditions from game theory,19 which represent a distribution where no subgroup of players has an incentive to be disengaged and create a solution on their own. It has been shown that designing a cost allocation of CJC in proportion to SAC can produce a Core solution. This was developed after vigorous academic debate during the 1980s20 and is termed the Moriarty/Louderback approach, but it suffers from heavy information demands, not least to estimate the SAC for all increments. Nonetheless, it has found application in postal markets21 by La Poste.

Similar comments on informational feasibility apply to using the Shapley value approach to design a cost allocation system that is deemed fair to different groups of products and customers. The use of the approach is discussed in academia for allocating costs in electrical transmission, mobile infrastructure and the cost of landing slots for airports, though confirmed examples of its use in public regulatory decisions are rare (one example is its use by ARCEP, the French postal regulator22).

Choosing between approaches

Context will affect the choice of approach. The first issue is the relative size of the CJC. If the ratio of the CJC costs to other costs is small then the use of a simple method such as EMPU may well be acceptable. The second issue is informational practicality; many alternatives have not found widespread use because the necessary information is not available. Where the way is open to assess alternatives, the key issue is the purpose of the product cost estimates.

- If the intention is to consider prices for access to a downstream supply chain, then a variation on LRIC (or a short-run AVC or AAC) may be appropriate. This may include ‘pure’ LRIC where the CJC costs would need to be recovered from other products or LRIC+, where the access price makes some contribution to CJC costs.

- If there is concern about foreclosure of a market against potential competition, for example, for prices that might be set too low, then LRIC costs are relevant. This would be relevant to an action regarding predatory pricing.

- If the concern is a claim focused on excessive prices then relevant cost standards might include ATC/FAC and the SAC, SAC Combinatorial or DSAC, which could all be important factors in justification of prices. A key principle in such cases, as explained by the CAT in Le Patourel v BT, is that firms in competitive conditions should enjoy a considerable degree of flexibility in how those costs are recovered, recognising of course that this flexibility is not unbounded.23

- For a periodic price control review by the regulator, there will usually be an interest in FAC, often supported by ABC, and those costs that cannot be traced by ABC will require an allocation basis. One approach, other than SAC, SAC Combinatorial or DSAC considered above, could be a Ramsey method if the prime objective is allocative efficiency. Alternatively, if the allocation must be perceived as fair by stakeholders, the Moriarty/Louderback or Shapley approaches could be used. These approaches aim to establish cost-oriented prices that stakeholders will view as advantageous compared to going-it-alone, thereby avoiding subsidy of any party

Conclusion

The hazard of unjustifiable cost allocations of indirect cost is growing with the advent of class actions against multi-product firms regarding their pricing policies, adding to the existing threat of actions from regulators and competition authorities. The penalties for predatory, excessive or discriminatory pricing can be large, so it makes sense to confirm in advance the acceptability prices vis-à-vis alternative cost allocation methods.

1 Le Patourel v BT Group Plc and Anr [2024] CAT 76 (hereafter, Le Patourel v BT).

2 ‘Indirect’ here means costs that are not directly allocated to products or services.

3 It is also possible to model costs on a forward-looking basis and to make selective adjustment to historic costs—for example, as regards depreciation.

4 International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (2024), IAS 2 Inventories (online). Available at https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/, accessed 28 February 2025.

5 International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) (2024), IAS 16 Property, Plant and Equipment. Available at: https://www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/, accessed 28 February 2025.

6 OECD (2022), ‘OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations’, January, p. 321.

7 ‘Discriminatory pricing’ is another hazard if there are unaccountable price differences for different customers.

8 Payment System Regulator (2018), ‘Onshoring EU Regulatory Technical Standards under the Interchange Fee Regulation’, November.

9 Some production processes can vary their ratio of outputs of multiple products, and in this case cost analysis depends on the mix being specified, usually to maximise the profitability of the firm.

10 Allocative efficiency refers to the efficient allocation of resources within a market, in contrast to productive efficiency that refers to the efficient conversion of input to output.

11 Unless corporate management have opted to include this functionality in the system, to provide decision support in their own work.

12 Oxera (2025), ‘Blending Incremental Costing in Activity-Based Costing Systems’, Agenda, February.

13 It is, however, possible to calculate the LRICs on a historic basis.

14 See Baumol, W.J., Panzar, J.C. and Willig, R.D. (1982), Contestable Markets and the Theory of Industry Structure, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

15 The ‘pure LRIC’ is the version of LRIC that includes no CJC whatsoever.

16 In the PPC case (BT v Ofcom [2011] CAT 5) the CAT noted at para. 254 that ‘combinatorial tests are one way of assessing whether or not a firm is over-recovering its common costs, and in some cases will be an entirely appropriate approach.’ Furthermore, in Le Patourel v BT, the CAT noted at para. 661 that ‘[…] in the context of PPC, [SAC Combinatorial] was simply impracticable. On the other hand, the exercise might not be impracticable in respect of a firm which had only 2 or 3 products.’

17 UKCTA (2011), ‘Call for Inputs: Review of cost orientation and regulatory financial reporting in telecoms’, December, remarks that ‘the DSAC/DLRIC approach may be appropriate and reasonable as a first order test. However there are examples of where such an approach simply does not work. For example in the context of [recent dispute], the difference between the floor and the ceiling is vast. If the obligation is to be between the floor and the ceiling, it therefore sets a range which is so wide as to become effectively completely meaningless’, p. 12.

18 Oxera (2005), ‘One size fits all? Cost allocation in postal services’, Agenda, August.

19 Serrano, R. (2009), ‘Cooperative games: Core and Shapley value’, in R. Meyers (ed.), Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science, New York: Springer.

20 Biddle, G.C. and Steinberg, R. (1984), ‘Allocations of joint and common costs’, Journal of Accounting Literature, provides an extensive review of the literature at the time, including the SAC approach.

21 Kalevi Dieke, A. et al (2012), ‘Cost standards for ex-post price control in the postal sector’, WIK discussion paper.

22 Op cit.

23 Le Patourel v BT, para. 907.

Related

Ofgem’s RIIO-ED3 SSMC

On 8 October 2025, Ofgem published its Sector Specific Methodology Consultation (SSMC) for the forthcoming RIIO-ED3 (ED3) price control for GB electricity distribution networks. We look at some of the key themes emerging from the consultation ahead of the final methodology decision, which is expected to be published in December… Read More

What are the challenges of decarbonising industry in the transition to a green economy?

Earlier this year, the European Commission set out its recommendations for implementing its clean industrial deal—aimed at supporting the EU’s decarbonisation goals while maintaining global competitiveness. Although sectors like electricity generation have seen substantial emissions reductions, many industrial areas still face a steep path ahead. In this episode of Top… Read More