‘Brexit means Brexit’, but will state aid rules in the UK be lost in transition?

State aid control became a focal point of the Brexit referendum debate in the UK in 2016. In a joint article with Dr Leigh Hancher, Professor of European Law at the University of Tilburg and Special Counsel at Baker Botts (Belgium) LLP, we discuss the government’s proposals for state aid rules in the UK if there is no deal, as well as a number of associated practical challenges.

During the Brexit referendum campaign, some proponents argued that leaving the EU would mean that the UK would have greater flexibility to embark on an active industry policy without the need to comply with state aid rules.1 Currently, there are various demands in the UK for greater public support, with the latest proposals branded as the ‘Kingfisher’ project.2

At first sight, the future application of the EU state aid regime within the UK after Brexit appears to be taken care of, irrespective of whether there is a deal.3 However, as discussed in this article, in the event of a no deal Brexit, the transition from an EU to a domestic state aid regime may not be entirely smooth, and it is possible that the framework adopted in the UK could diverge from its EU heritage.4 The prospect of a no deal Brexit therefore raises a number of questions about state aid enforcement procedures in the UK, particularly in relation to existing European Commission decisions, appeals in front of the EU courts that are ongoing at the time of exit, as well as aid that has been notified to the Commission where a decision is pending.5

What might happen to the control of state aid in the UK after Brexit?

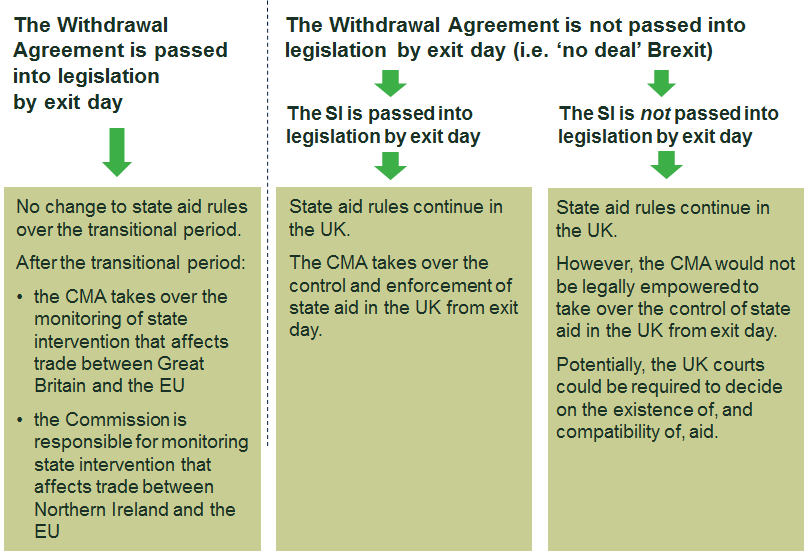

If the draft Withdrawal Agreement is approved, after exit day there would be no change to state aid rules until after the end of the transition period.6 At the end of this period, provisionally set for 1 January 2021, the UK’s competition authority, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), would become responsible for monitoring aid that affects trade between Great Britain and the EU.7

In the event of a no deal Brexit, the EU’s state aid regime, as it stands, would be transposed into domestic law in the UK as of exit day.8 If the proposed secondary legislation that adapts the EU’s regime to the UK context is passed into legislation by exit day, the CMA would become responsible for monitoring the new ‘domestic state aid regime’ as of exit day.9

However, if the secondary legislation is not passed in time, while state aid rules would continue in the UK, based on the EU’s current framework, there would be question marks about the authority that would be required to enforce state aid rules in the UK. Under the EU Withdrawal Act 2018, the UK government would be prevented from granting aid until it has been approved as compatible with state aid rules; however, neither the Commission nor the CMA would have the authority to do this.10 It is possible that UK courts could be required to decide on the existence of, and compatibility of, aid in such circumstances until the secondary legislation is passed.11

Figure 1 summarises these possible scenarios.

Figure 1 What could happen to the control of state aid in the UK post Brexit?

Source: Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, as endorsed by leaders at a special meeting of the European Council on 25 November 2018; the EU Withdrawal Act 2018; and the Draft State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 Statutory Instrument.

The absence of any deal could lead to a number of changes to the state aid framework in the UK.

The test under Article 107 TFEU of whether state intervention has the potential to distort trade between EU member states would be replaced by a test of whether state intervention has the potential to distort trade between the UK and the EU (see the box below). Although there would be no equivalent obligation on the EU to consider the impact of aid in the EU on the UK, the implications of this are likely to be limited in practice, as such measures would be likely to affect trade within the EU, and thereby fall within the scope of state aid rules.12

The definition of state aid in the UK according to the draft secondary legislation

Under the draft EU Exit Regulations 2019 SI, state aid is defined as:

Any aid granted by the state or through state resources in any form whatsoever which distorts or threatens to distort competition by favouring certain undertakings or the production of certain goods shall, in so far as it affects trade between the United Kingdom and the European Union, be prohibited unless it is approved in accordance with Article 108(3) of the TFEU. [Emphasis added]

Source: HM Government (2019), ‘The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, 3(2) and (4).

Under the draft secondary legislation, the CMA would take over from the Commission as the state aid regulator in the UK. Although the CMA would be required to adopt the Commission’s existing state aid guidance, in a number of areas the state aid framework in the UK may differ from the Commission’s approach.13

First, the UK would not be required to follow the ‘common rulebook’ to ensure full consistency over time with the EU’s state aid rules and precedent from the European Court of Justice.14 This could lead to uncertainty for aid grantors and recipients, at least until there is a sufficient number of precedent cases under the domestic UK regime.

Furthermore, the CMA would be required to have regard to guidance to be issued by the Secretary of State when assessing whether aid is compatible with state aid rules.15 As any analysis of whether the positive effects of aid outweigh any negative effects inevitably involves some degree of subjectivity, there is potential for certain aspects to differ from the Commission’s approach. In particular, given that the UK would be outside the EU, it is possible that the weight placed on the assessment of whether state intervention unduly affects trade with the EU could differ from the Commission’s approach, as well as the interpretation and assessment of whether state intervention contributes to objectives of common EU interest.16

Second, the CMA would not be granted the power that the Commission has to set aside an Act of the UK Parliament on the basis that it involves incompatible state aid. While the CMA could report on whether an Act of the UK Parliament such as a tax exemption involves state aid, and if so, whether it is compatible, the UK Parliament would not be required to take into account the CMA’s opinion.17 In such a scenario, if there are no obligations on the UK government to notify a general act to the CMA, there would be few rights for third parties such as competitors.

Despite this, there would, however, be some advantages relative to the Commission’s framework in terms of state aid procedure.

- Notification to the CMA could be made by the aid grantor directly, avoiding the need for all communication to be via the UK government.18

- Shorter timescales are targeted compared with the Commission’s regime in certain areas. In contrast to the Commission’s framework, if the CMA fails to meet a deadline of 40 working days to approve aid after the final notification has been submitted, or to start an in-depth investigation, the aid could be implemented providing that the CMA is informed.19

In the event of a no deal Brexit, could transitional problems arise?

In the absence of pre-agreed rules to govern a smooth transition in the event of a no deal, there are several scenarios where ‘transitional’ problems may arise. In particular, there would be no clear arrangements to deal with ‘live’ state aid cases, which would create potential risks and uncertainty for business. Three problematic scenarios are considered below.

What would happen to aid that has been notified to the Commission, but not yet approved, prior to Brexit?

According to the draft secondary legislation, any aid measures or schemes not yet approved by the Commission as of exit day would have to be re-notified to the CMA. However, would that mean that the Commission would automatically lose jurisdiction? Any investigation allocated a case number by the Commission could potentially remain a ‘live’ EU case, especially if the aid measure or scheme in question has affected trade with the EU prior to the UK’s exit.

It is important to recall that the Commission’s eventual decision on a live case after Brexit would no longer be addressed to the UK, as it would no longer be a member state. The Commission’s Procedural Regulation envisages only the member state as an addressee for state aid decisions, irrespective of the type or stage of the procedure.20 This distinguishes the state aid regime from other areas of EU competition law, such as a merger filing, where Commission decisions are addressed to the undertakings concerned. For these reasons, it is unclear what might happen to aid that has been notified to the Commission, but not yet approved, prior to Brexit.

What would be the implications of a no deal Brexit for aid deemed unlawful by the Commission prior to Brexit but not yet recovered?

In the event of a no deal Brexit, there are question marks about whether the UK would be required to honour recovery orders from the Commission for aid that had been deemed unlawful before Brexit by the Commission, with an order for recovery that is addressed to the UK as a member state.

Although recovery orders against the UK have been relatively rare, the ongoing case relating to the group financing tax exemption under the UK’s Controlled Foreign Company (CFC) rules is a notable exception, and illustrates the potentially problematic issues that could arise in the event of no deal (see the box below).

The Controlled Foreign Company investigation

On 2 April 2019, the Commission concluded that a tax break introduced in the UK through the reforms to the CFC rules under the Finance Act 2012 constituted unlawful state aid to certain multinationals. Between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2018, the UK’s CFC rules included a tax exemption—the Group Financing Exemption (GFE), which provided a full or partial (75%) exemption for finance income (specifically, interest payments on loans) between non-UK members of a corporate group.

The Commission concluded that:

- if the GFE relates to finance income that is not generated from UK activities, the exemption is justifiable and proportionate and therefore does not constitute aid;

- if the GFE relates to finance income derived from UK activities, the exemption is not justified, as it provides a selective and unjustified advantage to multinationals that could benefit from the exemption relative to their competitors that are required to pay the UK standard rate of tax.

The UK has been directed by the Commission to reassess the tax liability of companies that have received unlawful state aid by using the GFE in respect of finance income from UK activities.

Source: European Commission (2019), ‘Commission Decision (EU) 2019/1352 of 2 April 2019 on the State aid SA.44896 implemented by the United Kingdom concerning CFC Group Financing Exemption’, Official Journal of the European Union, 20 August, L 216/1.

In the event of a no deal Brexit, there would appear to be no legislative obligation for the UK to be required to recover the aid, as the UK would cease to be a member state.21 However, the UK was a member state at the time of the Group Financing Exemption, and when any alleged advantage would have accrued to the beneficiaries prior to Brexit.

On 19 June 2019, the UK applied to the General Court for annulment of the Commission’s decision, and actions for annulment have also been lodged by various companies that would be affected by the recovery order.22 The General Court will have to consider whether the UK and the beneficiaries would still have formal standing to bring annulment actions. If the General Court allowed the action to proceed and concluded in support of the Commission, what would happen next?

The CFC case is not the type of ‘live case’ that could eventually be assessed by the CMA, as the CMA would not have the power to assess general legislative acts, and it would therefore not be able to take over the recovery process.

What would happen if, after Brexit, the European Courts set aside a pre-Brexit Commission decision declaring aid to be compatible?

In November 2018, the General Court annulled the Commission’s approval of the UK’s capacity market scheme.23 The General Court found that the UK’s capacity auction rules appeared to be prima facie discriminatory, and that the Commission should have opened a full investigation before declaring the aid to be compatible.

The Commission has appealed the General Court’s ruling to the European Court of Justice. If it is successful, at least in theory, the case could be sent back to the General Court. However, if the measure—which relates to events in 2014—is held to be discriminatory, and if, on the conclusion of the Commission’s ongoing formal investigation, it is held to be unlawful state aid, what would be the consequences? Can the aid still be recovered, and which authority would enforce the recovery? The CMA may be unlikely to assess a past measure if it is no longer applicable in the UK post Brexit.

It should be noted that the draft secondary legislation is entirely silent about appeals of CMA decisions24—the only remedy for anyone wishing to challenge a CMA decision would be judicial review in the High Court.25

Will state aid rules be lost in transition?

The answer to this question is ‘no, subject to some important caveats’. As discussed in this article, state aid rules would continue in the UK, based on the EU’s current framework, if there is a no deal Brexit.

However, a number of challenges could arise if there is no deal, with the potential for the UK state aid regime to differ over time from its EU heritage. In the short to medium term, this may lead to additional uncertainty for aid grantors and potential aid beneficiaries, at least until there are a sufficient number of precedents under the domestic UK regime.

With exit day looming, it therefore appears that state aid rules may yet continue to attract attention and debate in the UK.

1 Institute for Public Policy Research (2019), ‘State Aid Rules and Brexit’, Briefing, January, p. 3. Article 107(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) defines state aid as state intervention in any form from any level of government that gives a business or another entity a selective economic advantage that could not be obtained in the normal course of business that has the potential to distort competition and trade between member states. If state intervention meets the criteria for the existence of aid, it would typically need to be notified to the European Commission, unless the aid met the criteria of the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER) or fell under the de minimis rules. The Commission would then assess whether the aid is compatible with state aid rules.

2 Holehouse, M. (2019), ‘Comment: UK state aid regime shrouded in Brexit fog’, MLex, 23 August.

3 HM Government (2018), ‘The Future Relationship Between The United Kingdom and The European Union’, July, section 1.6.1; and HM Government (2019), ‘Explanatory memorandum to the State aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, para. 7.1.

4 Such concerns were already highlighted in late 2018. See Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2018), ‘Government Response to the House of Lords EU Internal Market Sub-Committee Report on the Impact of Brexit on UK Competition and State Aid’, 29 March.

5 This article does not discuss the World Trade Organization rules on subsidies (namely, the Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures), and their potential application to the UK as a third country.

6 The Commission would have the power to take actions to address any unlawful state aid awarded during the transition period and for four years afterwards. According to the draft Withdrawal Agreement, Commission decisions that result from these investigations would be binding ‘on and in’ the UK, and private parties as well as the UK government would be bound by the Commission’s decisions.

7 However, according to the draft Withdrawal Agreement, state intervention that affects trade in goods between Northern Ireland and the EU would remain subject to EU state aid rules, including enforcement by the Commission and the European Court of Justice. This distinction has the potential to lead to legal disputes, with measures such as a government grant scheme open to all UK businesses potentially falling under both regimes. For further details, see Draft Agreement on the withdrawal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland from the European Union and the European Atomic Energy Community, as endorsed by leaders at a special meeting of the European Council on 25 November 2018.

8 EU Withdrawal Act 2018, section 4. The EU Withdrawal Act 2018 transposes the EU state aid regulations and certain Commission decisions into domestic law as they stand as of exit day. Under section 8 of the EU Withdrawal Act, the Secretary of State may introduce statutory instruments to correct any failure of retained EU law to operate effectively in the UK when it is a third country.

9 At the time of writing this article in early September 2019, the secondary legislation—the State aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019 Statutory Instrument—has not yet been passed into legislation.

10 The exception is that aid that meets the requirements of the General Block Exemption Regulation (GBER) would not need to be notified.

11 This point has been informed by discussions with George Peretz QC at Monckton Chambers.

12 In light of the low threshold under the state aid framework of what may constitute a potential impact on trade, an intervention by the state in one EU member state is likely to have the potential to distort trade with other EU member states, thereby remaining within the scope of state aid rules.

13 HM Government (2019), ‘Explanatory memorandum to the State aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, para. 7.12.

14 Under the new ‘domestic’ regime, interested parties, such as competitors, can exercise their rights before the domestic courts to ensure notification and standstill (i.e. the prohibition on the implementation of the measure) until the CMA decides on the status and eventual compatibility of the aid. However, in contrast to the Commission’s current approach, the only remedy to challenge a CMA decision would be judicial review in the High Court.

15 HM Government (2019), ‘Exiting the European Union, Competition, The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, 5(2); and HM Government (2019), ‘Explanatory Memorandum to The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, para. 11.1.

16 The assessment of common interest objectives is typically undertaken from the perspective of the EU as a whole, and provides a tool for assessing whether aid leads to ‘positive integration’. See Blauberger, M. (2008), ‘From Negative to Positive Integration? European State Aid Control Through Soft and Hard Law’, Max Planck Institute Discussion Paper, April, p. 7.

17 Although there are no specific provisions to this effect, it is likely that the Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish governments would be fully subject to the notification requirements, and would be required to take into account the CMA’s findings. HM Government (2019), ‘Explanatory Memorandum to The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, para. 6.27.

18 However, in the CMA’s draft guidance, ‘central coordinators’ have been proposed, particularly in Scotland and Wales. See Competition and Markets Authority (2019), ‘Draft procedural guidance on state aid notifications and reporting’, 4 March, para. 4.1. HM Government (2019), ‘Exiting the European Union, Competition, The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, 7(1).

19 HM Government (2019), ‘Exiting the European Union, Competition, The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, 8(1). Peretz, G. (2019), ‘The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019: some initial comments’, UK State Aid Law Association, 19 February.

20 According to the Commission’s Procedural Regulation, following a finding of unlawful state aid, the member state is obliged to take action to recover the funding from the beneficiary with interest backdated to when the aid was awarded.

21 There would also be no basis on which to do this through World Trade Organization rules.

22 For details, see European Commission, ‘SA.44896 State aid scheme UK CFC Group Financing Exemption’.

23 General Court of the European Union, Judgment in Case T-793/14, Tempus Energy Ltd and Tempus Energy Technology Ltd v Commission, 15 November 2018.

24 Apart from a reference in Schedule 5 to appeals to the court against administrative penalties.

25 HM Government (2019), ‘Explanatory Memorandum to The State Aid (EU Exit) Regulations 2019’, section 7.15.

Download

Related

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More