Can the private sector help to get the rail industry back on track?

The GB rail industry is facing considerable challenges. Low passenger numbers mean that a massive increase in state subsidy has been necessary to keep services running, which is unsustainable. To what extent could revenue growth be incentivised in train operators’ contracts? Oxera analysis commissioned by Rail Partners has found that a shortfall in passenger revenue can be offset by changing contracts to grant greater commercial flexibility to operators, while providing stronger incentives to grow revenue.

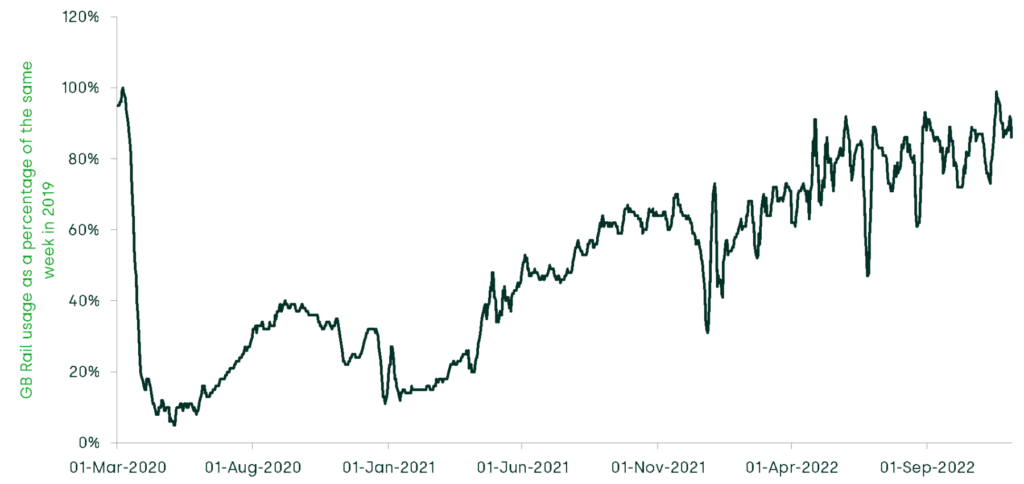

The GB rail industry faces an uncertain future in a post-COVID-19 world. Rail usage has recovered somewhat following the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, but still remains below its pre-pandemic peak. As of December 2022, passenger numbers on Britain’s railways were c. 85% of what they were before COVID-19.

Figure 1 Rail usage in Great Britain from March 2020 to December 2022

This decline in patronage has had a considerable impact on the sector’s finances: government funding of the rail industry in the year to March 2022 was £13.3bn, which is almost double the level of funding provided in the year before COVID-19 (i.e. £6.8bn).1 While the financial sustainability of the industry was already being called into question before the pandemic, this deterioration in circumstances is worse than even the greatest critics of the old franchising model might have foreseen.2

This shock to the industry’s finances is exacerbated by recent industrial action, which may be causing further shifts in travel habits, as passengers reassess how—and, indeed, whether—they travel.

Two approaches could be undertaken to resolve the industry’s finances. One would involve the state continuing to contribute cash, to ensure that services are maintained despite the fall in demand. Such an approach appears untenable given funding pressures elsewhere in the UK public sector, including notably in the NHS and supporting consumers through the energy crisis.

Another approach would be to eliminate the funding shortfall by modifying the price/service combination provided to passengers. This would mean raising fares, reducing services, or some combination of the two—although this would only further reduce demand.

In practice, the solution could also involve a rebalancing of services, with fewer commuter trains and more long-distance services to serve leisure markets. This would require careful analysis and coordination to avoid a ‘death by a thousand cuts’, which would otherwise emerge from piecemeal service reductions that could harm connectivity and network effects.

This raises two questions in particular: how can the downward spiral be stopped? And what role, if any, should the private sector have in this?

Oxera supported Rail Partners, the GB trade body for rail passenger owning groups, their train operating companies and rail freight companies in addressing these questions in a recent report.3 The report concludes that much can be done to improve the industry’s finances by providing stronger incentives, and greater commercial freedom, in rail contracts for operators to grow revenues.

Oxera’s analysis demonstrated that the contracts introduced by the Department for Transport (DfT) following the pandemic—under which train operators share no revenue risk and have limited commercial flexibility—are costing the rail industry between £800m and £1.1bn per year in reduced revenues. Were these effects to persist over the remaining two years of the current spending review period, the total loss in revenue would be between £1.6bn and £2.1bn.4

In light of this evidence, Rail Partners’ report outlines the following four recommendations:

- mechanisms that are available within train operators’ existing contracts with the DfT to incentivise operators to grow revenue should be immediately activated;

- operators should be provided with greater influence over commercial levers, including timetabling, marketing and fares, to respond to new incentives to grow revenue by improving the offer to customers;

- in future, Great British Railways (GBR, the new state-owned body envisaged in the ‘Plan for Rail’5) should tender a spectrum of ‘Passenger Service Contracts’, with revenue incentives calibrated to fit the specific market in question;

- the DfT should take a holistic view of revenues and costs, rather than continuing to focus exclusively on cost reduction, which is negatively affecting passenger experience and the industry’s finances.6

It appears that some parts of the government may be moving towards a similar position. Recent reports suggest the GBR Transition Team—responsible for setting up the new state-owned body—now favours ‘progressively dialling up the level of cost and revenue incentivisation and risk transfer within service contracts, starting immediately’.7 This is despite the fact that, at least in theory, the Plan for Rail envisages GBR taking revenue risk across most of the network.8

In light of this, it may be reasonable to conclude that the solution is simple: give train operators the freedom to tailor their services based on their customers’ needs, and let them share in the upside (and downside) so that they have an incentive to grow revenue. This will help to close the funding gap, which should in turn help to solve the downward spiral outlined above. Right?

We address this reasoning below—but first it is helpful to have a brief look at the history of franchising in GB rail, from privatisation to COVID-19.

How did we get here?

Immediately following privatisation, most franchises were tendered under full revenue risk. This meant that, when bidding for franchises, owning groups would forecast the costs and revenues that they thought they could deliver from running services, and—after accounting for their profit margin—offer to pay the state the difference (or offer to receive a payment for the difference, where expected costs exceeded expected revenues).9

Initially, train operators were able to earn positive returns. However, subsequent franchises were tendered on less generous terms,10 with operators soon running into financial difficulties. There is evidence that this was driven in part by overly optimistic bidding.11

To help improve financial stability, in the next round of franchising the newly created Strategic Rail Authority developed a new risk allocation mechanism, called ‘cap and collar’. This committed the government to providing revenue support to the operator if revenue fell below pre-determined levels, and allowed the government to share in any outperformance in revenue above predetermined levels.12

While ‘cap and collar’ helped to improve financial stability, it had two key drawbacks. First, the mechanism diluted incentives for train operating companies (TOCs) to grow revenue, particularly when an operator was in the outer bands of revenue share or revenue support (an 80% sharing rate usually applied at this point, meaning that a TOC in revenue support would have no incentive to invest in a scheme unless it expected a payback at least five times greater than its investment costs). Second, the comparatively weak incentives for operators to grow revenue created problems for the government in forecasting and managing public expenditure.13

Following the collapse of the InterCity West Coast franchise competition in 2012, the government commissioned a review from Richard Brown into the DfT’s rail franchising programme. The review outlined a number of recommendations, including that:

- contingent capital requirements (setting out the minimum amount of capital that franchise operators were required to hold) should be set at a level that would create financial robustness, deter defaults and protect the government up to a reasonable limit for a loss of premium (or increase in support) in the event of any default;

- to ensure that TOCs were not exposed to risks outside of their control (which risked increasing default risk and/or raising the profit margins that TOCs would bid to operate franchises), the DfT should introduce ‘exogenous risk share mechanisms’ to protect franchisees from the impact of movements in GDP on revenues.14

In the years that followed, the DfT tendered a number of franchises using these new exogenous risk share mechanisms. The first, InterCity East Coast, included a GDP indexation mechanism: this specified the revenue support (or share) payments that would apply in the event that GDP growth fell below (or exceeded) the growth-rate forecast at the time when the franchise was tendered.15 Later franchises were tendered using similar mechanisms, including ‘CLE’ mechanisms, which provided revenue support or share payments to commuter TOCs based on unexpected movements in central London employment.16

Alongside this, the DfT introduced a new method for setting contingent capital requirements for franchises, with the amounts set based on how ambitious owning groups’ financial projections (and therefore bids) were.17

While the new framework was initially deemed successful—with high levels of appetite from owning groups to bid for franchises—problems gradually began to emerge. The GDP/CLE mechanisms still left operators exposed to large amounts of risk outside of their control, since mechanisms could not be calibrated to shield operators from all forms of external risk. This was manifested most notably with the collapse of the East Coast franchise in 2018.18

This drove large capital requirements for franchises, with owning groups tying up large amounts of shareholder capital on individual franchises.[19] This, in turn, reduced interest for UK rail franchises tendered in the latter half of the last decade, with only two bids for the West Midlands and South Western franchises.20

To address these issues, the DfT introduced a new risk transfer mechanism, known as the Forecast Revenue Mechanism (FRM).21 This was similar to ‘cap and collar’, albeit with some key differences, including that:

- revenue support and share payments could be triggered earlier in the franchise term;

- contractual incentive mitigations (CIMs) were introduced.

CIMs were a set of obligations imposed on operators in the event that FRM payments were triggered during the franchise term. Their aim was to minimise the risk of perverse behaviours by train operators materialising as a result of FRM payments diluting incentives to grow revenue. Examples included minimum requirements for annual marketing expenditure; DfT scrutiny regarding proposed changes to fares; and surveys of passengers travelling without tickets (with high levels of ticketless travel sanctioned through penalty payments by train operators).22

The West Coast Partnership and the East Midlands franchise were tendered under the FRM.23 The mechanism was also used for a number of directly awarded (non-competed) contracts.24

Finally, following the onset of the pandemic in early 2020 and the resulting decline in passenger numbers, the DfT suspended all rail franchise agreements for six months. The existing contracts were initially replaced with new Emergency Measure Agreements, and subsequently Emergency Recovery Measures Agreements. Under these contracts, the government effectively retained all revenue and cost risk.25 More recently these contracts have been replaced with National Rail Contracts (NRCs). While these contracts include incentives for train operators to grow revenue, they have not yet been fully activated. In any case, the potential upside for operators is so limited that—in practice—the government continues to retain all revenue risk (and most cost risk).26

Where do we go from here?

The status quo, in which government retains all revenue risk and leaves train operators no real flexibility to tailor services for customers, is unlikely to be sustainable. Given the industry’s current financial difficulties, there is an opportunity to create an incentive framework that leverages the commercial expertise and innovation of operators.

At the same time, however, a quick review of the history of revenue risk allocation in GB rail contracts demonstrates that designing an ‘optimal’ contract is inherently challenging. In particular, the DfT (and, eventually, GBR) could ensure that any form of revenue risk allocation does the following.

- Provide good incentives—in particular, for TOCs to grow revenue by delivering the best price and service offer for passengers, good value for taxpayers, and wider benefits to the economy, while also avoiding perverse incentives (both at the point when contracts are tendered and during the life of the contract).

- Promote financial stability. While there is always a risk that commercial counterparties will enter financial difficulty, the DfT/GBR could avoid allocating risk in ways that increase the risk of mass defaults across the board.

- Ensure that contracts are attractive to owning groups, and that margins offered reflect an appropriate balance of risk. It can be tempting for policymakers to design contracts that minimise any opportunities for profit making—but squeezing profit margins too far can make contracts commercially unattractive. This can result in train-operator owning groups being less willing to invest, and—when contracts are ultimately retendered—reduce the number of bidders per contract, which in turn can lead to worse outcomes for taxpayers.

Rail Partners recommends that contracts should be tailored to reflect the nature of the market in question. Where contracts cover flows with large degrees of discretionary travel (usually long-distance markets) and operators have a greater degree of flexibility with regard to timetabling and fares, it suggests that this could be achieved through the re-introduction of the FRM. In contrast, it suggests that more narrow revenue incentives may be appropriate where train operators have less flexibility and there are lower degrees of discretionary travel, which is more likely to be the case when contracts cover commuter-dominated flows.27 This is consistent with Oxera’s analysis, which indicates that more risk should be allocated to operators where they have the commercial flexibility to manage those risks.

Importantly, this appears to be consistent with the Plan for Rail, which acknowledges that:

Revenue incentives will be built into contracts to grow passenger numbers, foster a culture of innovation and introduce efficiencies that deliver real benefits for passengers.28

This demonstrates that there is scope, within the original framework of the Plan for Rail, to develop a spectrum of contracts with different degrees of revenue risk allocation tailored to the market in question.

If so, the next question is this: how can the DfT and GBR develop contracts that transfer a greater degree of revenue risk to TOCs, while avoiding some of the issues experienced historically?

Solving this problem is beyond the scope of this article. However, the answer is likely to involve the following.

- Addressing long-term forecasting risks. Where a greater degree of risk transfer is appropriate,contracts are likely to be allocated (at least in part) based on operators’revenue projections. Where this is the case, the DfT and GBR need to recognise that forecasting revenues over a long time horizon is challenging. This means that, to allocate a greater degree of revenue risk to an operator while keeping default risk constant, the DfT/GBR must either:

- introduce reset mechanisms into contracts;

- reduce the contract term; or

- increase contingent capital requirements.

Shorter contracts may reduce train operators’ incentives to deliver initiatives during the contract term, since the benefits of any investments made by the train operator may be reaped by another operator (should the incumbent fail to re-secure the contract when it is next re-tendered). Shorter terms would also entail higher transaction costs.29 Meanwhile, increasing contingent capital requirements could reduce the bidding appetite for contracts. Accordingly, periodic reset mechanisms in contracts—where feasible—may be preferable.

- Financial ‘pain’ for poor performance. Where train operators deliver poor performance, this should affect their bottom line. This will ensure that TOCs have the right incentives to deliver good performance during the life of the contract, and minimise the risk of owning groups ‘overbidding’ for franchises.

- Close monitoring of the efficacy of the FRM. We agree with Rail Partners that the FRM could be one way of allocating revenue risk in future. Unfortunately, the arrival of the pandemic in 2020 meant that there was an insufficient time horizon to properly evaluate the efficacy of this mechanism, and in particular, whether the CIMs helped to mitigate perverse incentives. Accordingly, if the FRM is used in future, the DfT/GBR would ideally commit to fully evaluating the efficacy of the mechanism and making changes to it if issues are identified in future.

The bottom line

The rail industry is facing challenging times. With UK public finances under significant pressure and a weak macroeconomic outlook, continued state funding to cover rail’s financial hole is unlikely to be sustainable. It is now incumbent on everyone in the rail industry—from the private sector to Whitehall—to work together to find a way through.

Oxera’s analysis of existing contract structures demonstrates that there is a missed opportunity to grow passenger revenue—owing to a lack of effective incentives. This is clearly undesirable, given the current context that the industry faces. At the same time, past experience demonstrates that the state cannot simply transfer all revenue risk to TOCs. Creative solutions are needed to ensure that operators once again have incentives to grow revenue, but which, at the same time, promote financial stability across the sector and avoid the problematic incentives that can arise under poorly designed contracts.

Our analysis provides some ideas for how this could be achieved. We recognise that none of this is easy, and that a lot more work is needed if the industry is to navigate around some of the tricky issues highlighted in this article.

But doing nothing is not a viable option. If the answer is for the government to retain existing contract structures—and continue telling TOCs how to set fares and services—the cycle of decline is set to continue.

1 Office of Rail and Road (2022), ‘Rail industry finance (UK) April 2021 to March 2022’, 29 November (revised 22 December 2022).

2 Since the 1990s, rail passenger operations in Great Britain have operated predominantly under a franchising model where the government runs competition for the right to run passenger services for groups of services in different parts of the country.

3 Rail Partners (2022), ‘A Fork in the Tracks: Attracting customers back to the railway’.

4 We used a fixed-effects regression model to isolate the impact that contract specification had on rail revenue from other drivers of rail revenue. We identified two forms of contract specification: i) where operators were contracted by the DfT; ii) where operators had ‘commercial freedom’, which included two Open Access operators (Grand Central and Hull Trains) and Merseyrail. For more details, see Rail Partners (2022), ‘A Fork in the Tracks: Attracting customers back to the railway’, November, pp. 18–24.

5 Department for Transport and Williams Rail Review (2021), ‘Great British Railways: The Williams-Shapps Plan for Rail’, May.

6 Rail Partners (2022), ‘A Fork in the Tracks: Attracting customers back to the railway’, November, p. 17.

7 Financial Times (2023), ‘Rail bosses urge ministers to restore powers to train operators’, 6 January.

8 Department for Transport and Williams Rail Review (2021), ‘Great British Railways: The Williams-Shapps Plan for Rail’, May, p. 30.

9 Brown, R. (2012), ‘The Brown Review of the Rail Franchising Programme’, p. 14.

10 House of Commons (2001), ‘Public Accounts – Fifteenth Report’.

11 It is notable that franchises that were let later in the process tended to see more aggressive subsidy reduction profiles in winning bids. Some have suggested that the winning bidders may have intentionally overbid strategically, with the aim of later re-negotiating the agreements. For example, see Nash, C.A. and Smith, A.S.J. (2006), ‘Passenger Rail Franchising – British Experience’, ECMT Workshop on Competitive Tendering for Passenger Rail Services, p. 9; and Oxera (2012), ‘Sold to the slyest bidder: optimism bias, strategy and overbidding’, Agenda, September.

12 Brown, R. (2012), ‘The Brown Review of the Rail Franchising Programme’, p. 14.

13 Department for Transport (2011), ‘Reforming Rail Franchising: government response to consultation and policy statement’, p. 9.

14 Brown, R. (2012), ‘The Brown Review of the Rail Franchising Programme’, p. 8.

15 The Secretary of State for Transport, Inter City Railways Limited, East Coast Main Line Company Limited (2014), ‘FRANCHISE AGREEMENT – INTERCITY EAST COAST’, p. 389.

16 For example, the East Anglia franchise included a joint GDP/CLE mechanism. See The Secretary of State for Transport, Abellio East Anglia Limited (2016), ‘EAST ANGLIA FRANCHISE AGREEMENT’, pp. 342–345.

17 For example, bidders for the Intercity East Coast franchise were required to commit £50m minimum Parent Company Support (PCS) and 7% of the difference between the winning bidder’s bid franchise payments and the DfT’s baseline franchise payments. See Department for Transport (2014), ‘InterCity East Coast – Invitation to Tender’, p. 111.

18 The Guardian (2018), ‘State takes back control of east coast mainline’, May.

19 For example, Stagecoach committed £165m in PCS for the Intercity East Coast franchise. See House of Commons (2018), ‘Transport Committee – Oral evidence: Intercity East Coast rail franchise’, p. 27.

20 Barrow, K. (2016), ‘MTR pulls out of West Midlands Franchise contest’, International Rail Journal;

Railway Pro (2016), ‘UK unveils South Western franchise documents for bidders’.

21 The DfT made it clear that the FRM was designed to address these specific issues in its response to the Transport Select Committee’s report on rail franchising; see Department for Transport (2017), ‘Rail franchising: government Response to the Committee’s Ninth Report of Session 2016–17’.

22 For example, see Department for Transport (2018), ‘WEST COAST PARTNERSHIP FRANCHISE AGREEMENT—VOLUME TWO’, pp. 249–263.

23 The West Coast Partnership was tendered with both the FRM and a GDP risk share mechanism.

24 For example, see The Secretary of State for Transport and First Great Western Limited (2020), ‘DIRECT AWARD FRANCHISE AGREEMENT NO 3 UNDER THE RAILWAYS ACT 1993 (AS AMENDED) relating to Great Western Franchise’, p. 599.

25 FirstGroup plc (2020), ‘Statement re further rail agreements with UK government’.

26 Under NRCs, operators are exposed to limited cost risk, since they are exposed only to costs borne in excess of an annual budget (unless otherwise agreed in advance with the DfT).

27 Rail Partners (2022), ‘A Fork in the Tracks: Attracting customers back to the railway’, November, p. 15.

28 Department for Transport and Williams Rail Review (2021), ‘Great British Railways: The Williams-Shapps Plan for Rail’, May, p. 58.

29 A key consideration here relates to the DfT/GBR’s capacity, since shorter terms would result in tendering and contracting being undertaken more frequently.

Related

Grey or Green Giants? Sustainability and (Exclusionary Abuse of) Dominance under Article 102 TFEU

The intersection of sustainability and competition law has gained increasing attention in recent years—particularly in the context of agreements, as evidenced by the new Horizontal Co-operation Guidelines from the European Commission,1 but also in discussions around merger control.2 However, one area remains underexplored: the role of… Read More

Collective actions: are consumers reaping the benefits?

When companies engage in price fixing, abuse their market dominance, or form illegal cartels, consumers and businesses can suffer but since 2015 in the UK and 2020 across the EU, collective actions are challenging these anti-competitive practices and are seeking compensation. Many of us may even be members of a… Read More