CMA PR19 Final Determinations

On 17 March, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published its summary of Final Determinations (FDs) of Ofwat’s PR19 price review for four disputing companies (Anglian Water, Bristol Water, Northumbrian Water and Yorkshire Water), following a reference from Ofwat at the request of each company.

This article provides commentary on three key areas:

- finance issues;

- cost assessment;

- outcome delivery incentives (ODIs).

We expect the CMA to publish its full report in approximately two weeks and will supplement this note with further details in due course.

Finance

Allowed return on capital (WACC)

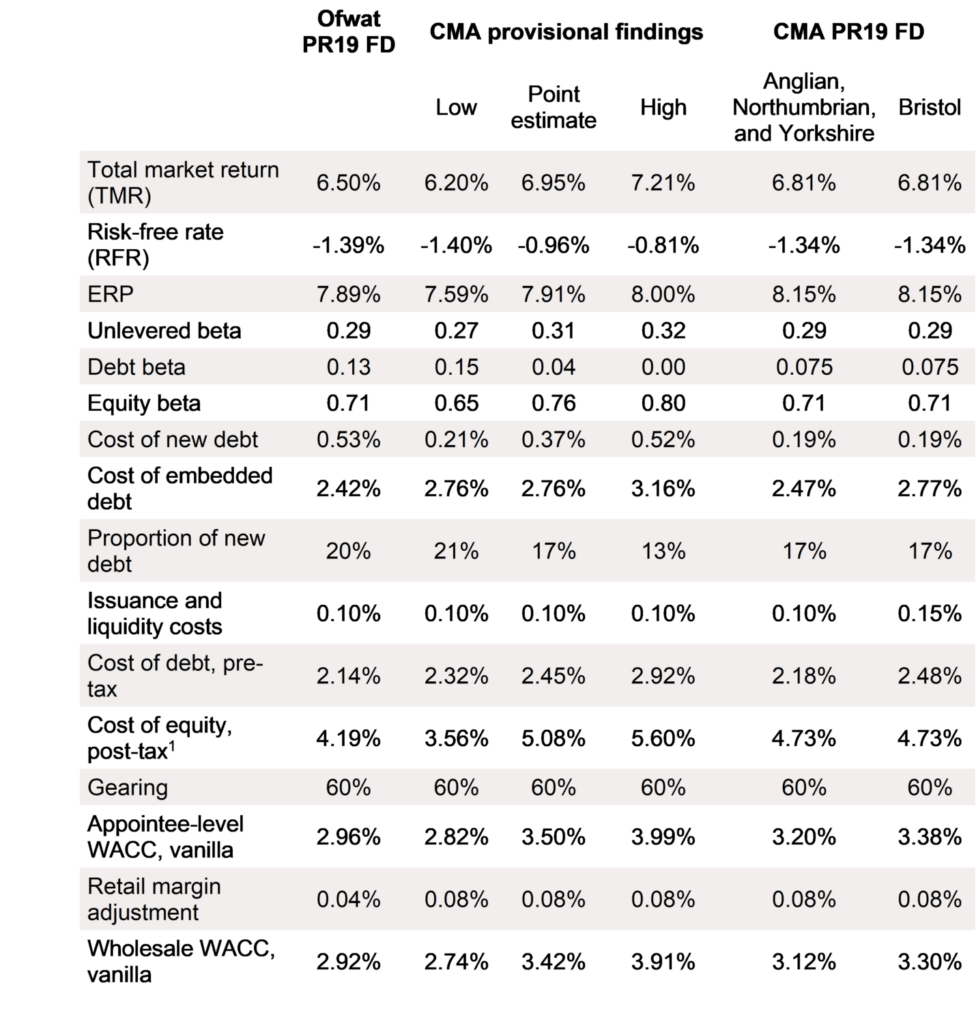

The CMA has set the wholesale allowed return on capital at 3.12% (CPIH, real) for Anglian, Northumbrian and Yorkshire. This is an increase of approximately 20bps for each company relative to Ofwat’s PR19 FDs, but approximately 30bps lower than the CMA’s provisional findings (PFs). The wholesale WACC for Bristol is 3.30% (CPIH, real) reflecting a relatively higher allowance for the cost of embedded debt and issuance and liquidity costs of 0.30% and 0.05% respectively.

Table 1 below shows the WACC parameters for the Ofwat FDs, CMA PFs, and CMA FDs.

Table 1 Allowed return on capital (CPIH, real)

Source: CMA (2020), ‘Anglian Water Services Limited, Bristol Water plc, Northumbrian Water Limited and Yorkshire Water Services Limited price determinations: Provisional Findings’, 29 September. CMA (2021), ‘Anglian Water Services Limited, Bristol Water plc, Northumbrian Water Limited and Yorkshire Water Services Limited Price Determinations, Summary of Final Determinations’, 17 March.

Cost of equity (CoE)

The CMA’s CoE estimate is 54bps higher than Ofwat’s FD, which is largely due to an increase in the total market return (TMR), a change in methodology for the risk-free rate (RFR), and explicit aiming-up of 25bps above the midpoint. Oxera made multiple submissions to the CMA on these parameters, mostly on behalf of the Energy Networks Association and Heathrow Airport. The increase in the CoE is the same for all four appellant companies, as the CMA has rejected Bristol’s application for a company-specific uplift on the CoE.

However, the CoE has decreased significantly at the FD—it is 35bps lower than at the PFs. This largely reflects a lower degree of aiming up on the CoE. The CMA aimed up to the 75th percentile on all the CAPM parameters at the PFs, which resulted in a point estimate 50bps above the mid-point. However, at the FD, the mid-point of each parameter is used and then an explicit 25bps adjustment is made to the CAPM-implied CoE estimate.

- TMR: the decline in the TMR point estimate stems from a change in methodology for aiming up on the CoE. The overall range, however, has increased from 6.2–7.2% to 6.2–7.5%, which indicates a change in the CMA’s estimation methodology. Oxera evidence focused on two issues: deflation of historical equity returns using RPI or CPI, and the calculation of average returns from the historical data.

- RFR: the decline in the RFR at the CMA PR19 FD is mainly due to a decline in market interest rates, as well as the methodological change to aiming up. However, the RFR is higher than the spot yields on government bonds, consistent with analysis provided to the CMA by Oxera.

- Unlevered beta: the unlevered beta has decreased from 0.31 at the CMA PFs to 0.29 at the CMA PR19 FD. At this point it is unclear how much of this is being driven by changes in methodology or market data.

- Debt beta: the CMA has increased the debt beta from 0.04 at the PFs to 0.075 at the FD, again due to the methodological change to aiming up.

- Equity beta: the lower unlevered beta and higher debt beta both result in a lower equity beta from 0.76 to 0.71.

Cost of debt

The allowed cost of debt is 2.18% (CPIH, real) for Anglian, Northumbrian, and Yorkshire, which is 4bps higher than Ofwat’s FD. Bristol’s allowed cost of debt is 2.48%.

- Cost of new debt: the CMA uses a six-month trailing average of iBoxx yields, as opposed to Ofwat which takes a spot estimate of the iBoxx yields and adjusts for the forward-curve implied premium and expected outperformance. Though these methodological changes are significant, the CMA’s FD estimate for the cost of new debt is approximately 35bps lower than Ofwat’s FD because it looks at more recent market data and yields have continued to decrease since Ofwat’s FD (and only recently begun to increase). The cost of new debt will be adjusted using an index at the end of AMP7, with the main change from Ofwat’s FD being the removal of the 15bp deduction for expected outperformance of the debt index.

- Cost of embedded debt: Ofwat and the CMA allow a similar final estimate for the cost of embedded debt—2.42% and 2.47% respectively. Bristol’s allowance in the CMA’s FD is 30bps higher than the allowance for Anglian, Northumbrian, and Yorkshire to reflect the higher historical financing costs of a small company (the small company premium) relative to an allowance that is based on the actual financing costs of larger companies.

- Issuance and liquidity costs: the CMA has kept the allowance the same at 10bps, except for Bristol which receives 15bps to reflect the higher average fees small companies may incur in interacting with financial markets. Ofwat’s allowance is 10bps for all companies.

Gearing outperformance sharing mechanism (GOSM)

Ofwat introduced the GOSM in PR19. Under this mechanism, companies with gearing above the ‘trigger’ level are required to share with customers some of the difference between the allowed cost of equity and debt. Ofwat argued for this by claiming equity investors benefit from the higher equity returns associated with their increased risk, but there is no substantive benefit passed to customers.

The CMA, in both its PFs and at the FD, found that there is not enough evidence to support the implementation of the GOSM in PR19. According to the CMA:1

We consider that the GOSM as designed was ineffective either as a benefit sharing mechanism or as a tool to improve financial resilience. […] we consider that Ofwat had not adequately evidenced the existence of the benefits from high gearing that it said would be available to share.

Financeability

The CMA finds that the appellant companies should be able to achieve strong investment-grade credit ratings based on the notional capital structure and allowed returns. In a reasonable downside scenario, the financial ratios deteriorate, yet they remain in investment-grade territory. The CMA considers that the overall package of risk and return has become less skewed than at Ofwat’s FD as the CMA has reduced risks in several areas.

In the event of a financeability constraint developing over AMP7, the CMA considers remedies would be available such as reducing headroom on financial ratios; foregoing dividends; or injecting fresh equity capital. The CMA finds that appellants’ determinations are financeable, and as a result it realigns pay-as-you-go (PAYG) rates with the ‘natural rate’ for each appellant. It does not consider advancing cash flows from future periods through Ofwat’s changes to PAYG rates to be credit positive. In particular:2

Our approach to assessing whether the Disputing Companies’ determinations are financeable is more consistent with the approach taken by the rating agencies. We were concerned that Ofwat’s approach would increase bills in the current price control without any confidence that it will in practice improve the credit-worthiness of the companies or, indeed, that on the contrary it might adversely affect financial resilience in the future which could result in higher costs for the companies and their customers.

For Bristol, Northumbrian, and Yorkshire, the ‘natural’ PAYG rate is the same as in Ofwat’s FD. For Anglian, the PAYG rate has increased to reflect the lower proportion of capital expenditure than in the CMA’s FD.

Cost assessment

The appellants’ total expenditure (TOTEX) allowances were adjusted upwards by the CMA relative to Ofwat’s PR19 Determinations, as shown in the table below. For three of the appellants, this TOTEX allowance was also higher than what the CMA had ruled in its PFs. However, Anglian’s TOTEX allowance in the CMA’s FDs is slightly lower than what the CMA had determined at the PFs.

Table 2 CMA Final Determinations on TOTEX (%)

| Anglian | Bristol | Northumbrian | Yorkshire | |

| Modelled base | 1.8 (0.5) | 7.9 (7) | 3.1 (3.4) | 3.9 (4.3) |

| Un-modelled base | 2.8 (2.2) | 2.4 (-2.3) | 6.9 (2.8) | 2.5 (2.2) |

| Enhancement | 2.9 (-3.7) | -1.0 (3.4) | 3.1 (-0.5) | 4.2 (-6.4) |

| TOTEX | 2.1 (-0.7) | 6.6 (5.4) | 4.3 (3.4) | 3.9 (1.6) |

Source: CMA (2020), op. cit.; CMA (2021), op. cit.

In PR19, Ofwat assessed base costs3 separately from enhancement costs. For base costs, this was primarily undertaken by benchmarking costs across the industry. The CMA has generally endorsed Ofwat’s base cost models and base cost assessment approach in its PFs and FDs.

Modelled base costs

While the CMA’s assessment of base costs was broadly similar to Ofwat’s, the CMA made several adjustments at the PFs. These adjustments include (i) excluding the alternative econometric models that were used by Ofwat in the PR19 determinations; (ii) updating cost driver forecasts with the latest data; and (iii) excluding one of Ofwat’s sewage collection models (SWC1) from its suite of models as the CMA ruled that the model was counterintuitive. The first two adjustments remain in the FDs, while the last adjustment is not discussed.

The use of most recent data

The CMA highlights that the largest contributor to the increased modelled base cost allowances for the appellants is related to the incorporation of 2019/20 data (that was unavailable to Ofwat for PR19) into its analysis. The use of 2019/20 for this redetermination has been intensely disputed, with Ofwat arguing that the use of the data will lead to an upward bias in the estimated cost allowances because it considered that 2019/20 was a high-cost year, while the appellants (and some third parties) argued that the most recent data must be used to ensure that expenditure cycles are properly captured. Indeed, the CMA provisionally decided not to use the 2019/20 data in a working paper published in January 2021,4 and has subsequently updated its view in response to parties’ submissions. Oxera made several submissions on this issue, representing three of the four appellants, arguing that the 2019/20 data must be used.

This decision (and the process that led to it) illustrates some important considerations. First, the use of any data that feeds into the benchmarking models should be robustly examined and challenged if necessary. Data can be excluded from the modelling if there are material concerns regarding its quality or its representativity. Second, there should be a high evidential bar for omitting data points from the dataset, particularly if there are conceptual advantages to including said data.

The incorporation of the 2019/20 data created novel modelling challenges due to the merging and reorganisation of Severn Trent Water and Dee Valley Water. Oxera proposed key guiding principles that should be followed when estimating econometric models and efficiency scores in this context to ensure consistency from an operational, modelling and benchmarking perspective. It appears that the CMA has followed similar principles in arriving at its decision. To the extent that industrial reorganisations are likely to occur in future price controls, these guiding principles may need to be developed further into a comprehensive framework.5

Accounting for the impact of quality on costs

In their statements of case, the appellants argued that there was a cost–service disconnect in Ofwat’s PR19 framework whereby service improvements were being set without consideration of the costs required to achieve those improvements. Oxera worked with two of the appellants and developed robust statistical and optimisation models incorporating measures of service quality into the cost assessment process. While we understand that the CMA has not updated its base cost models in the FD, the CMA has strongly supported principled statements regarding the operational reality that efficient companies require more expenditure to improve some outcomes. For example, the CMA states:

We [the CMA] have concluded that there is a link between maintaining higher performance on leakage and costs such that the base cost model we used will not adequately compensate all companies that are maintaining performance above the upper quartile […] the Disputing Companies which demonstrated that further enhancement allowances were needed to meet the ambitious leakage PCs should be allocated an allowance for the efficient costs of these enhancements. [emphasis added]

As a result of this view, the CMA increased the base allowances for one appellant to reflect the cost associated with maintaining high leakage performance. The CMA also made an enhancement allowance for three of the appellants to reflect the costs associated with improving their leakage performance.

Stringency of the benchmark

A key part of Ofwat’s cost assessment framework involved identifying a benchmark for setting efficient cost levels for companies. With regard to this aspect of Ofwat’s framework, the disputing companies challenged Ofwat’s choice of third or fourth company as the benchmark, which was more stringent than the upper-quartile (UQ) benchmark that Ofwat had applied in the draft determinations and previous price controls. Ofwat argued that the increased stringency of the benchmark was justified, given the supposed improvements in model quality and the increased cost allowances generated from changes to the framework.

At the PFs, the CMA considered that the quality of the econometric models was the key factor in determining the appropriate benchmark. It determined that Ofwat’s benchmark was too stringent and provisionally decided to move the benchmark back to the UQ. The CMA has retained this decision in its final determination with the incorporation of the 2019/20 data consistent with the Oxera submissions on behalf of the three disputing companies. It has noted that the UQ provides a ‘challenging benchmark whilst acknowledging the limitations of […] econometric modelling’.6

Frontier shift and real price effects

As well as identifying efficient cost levels by benchmarking companies’ costs, Ofwat applied an ongoing efficiency assumption of 1.1% p.a. to capture technological progress. Oxera supported one disputing company and the Energy Networks Association on the issue. In the PFs, the CMA reduced Ofwat’s frontier shift assumption to 1.0% p.a. but applied this to more wholesale costs (including all enhancement expenditure). The CMA reasoned that the frontier benchmark was based on the total cost base of comparator sectors. In the final Decision, the CMA has retained the 1% challenge, but has amended its application, either by excluding it on some of the cost items or applying it in a way that avoids double counting.

In line with Ofwat’s approach, the CMA has provided a real price effect adjustment for labour costs and a reconciliation (or true-up) mechanism for these labour costs if there are differences between forecasts and actual wage inflation.

Unmodelled base costs

At PR19, Ofwat identified several base cost categories that were unsuitable for econometric modelling (such as business rates, abstraction charges and costs associated with the Traffic Management Act (TMA)) and assessed these separately. The CMA’s approach to assessing this type of expenditure is similar to Ofwat’s, with the following key distinctions.

- The cost sharing rates for some of these expenditure items (such as business rates) should differ from those applied to other aspects of the cost base given the relatively limited management control over these costs. At the PFs, the CMA determined that a 90:10 (customer:company) sharing rate was appropriate.

- In a change from the PFs, the CMA concluded that frontier shift efficiency challenges should not be applied to business rates and abstraction charges, owing to the fact that these costs are largely outside of management control.

These changes to the framework (and a correction to Northumbrian’s data) lead to an increase in appellants’ unmodelled cost allowances of c. £46m. Given the cost sharing rates, most of the outperformance or underperformance on these allowances will be shared with or borne by the consumers.

Enhancement expenditure

On leakage, Ofwat encouraged companies to submit challenging performance targets in their business plans, but only allowed enhancement expenditure for those companies that were already strong performers on leakage. The CMA disagreed with this approach, and allowed Yorkshire £28m compared to a £0m allowance under Ofwat’s determination. While this is a material increase relative to Ofwat’s determination, it is still significantly below the c. £90m that the company requested.

Meanwhile, WINEP is a large driver of enhancement costs for wastewater. Relative to Ofwat’s PR19 FDs, the CMA has accepted that phosphorus removal (P-removal costs) is a complex area where costs are driven by a range of different factors. In particular, the CMA has recognised key areas that Oxera and the appellants have submitted on, including the impact of first-time consents and catchment solutions on P-removal costs. This builds on previous developments in Ofwat’s assessment of WINEP costs, where Oxera has submitted evidence on the role of treatment complexity at the PR19 draft determinations and legislative drivers at the PR19 FDs.

Finally, in line with its PFs, the CMA has decided to apply a frontier shift efficiency challenge to all enhancement expenditure, leading to reductions in enhancement allowances for all companies. Oxera highlighted, on behalf of two appellants, that this would lead to a double-count of the frontier shift efficiency challenge, as frontier shift is already baked into the companies’ business plan data (that feeds into the enhancement models) and the company-specific efficiency challenges that are applied to deep and shallow dives. The CMA now states that it has applied the efficiency challenge ‘in a way that avoids double-counting’,7 but the exact method of doing so is not presented in the summary. We will comment on this further once the full findings are published.

Outcome delivery incentives (ODIs)

Changes in the CMA’s position since its PFs

The CMA has largely maintained the same position on outcomes as in the PFs. There are minor changes in three areas.

- Leakage: the CMA provisionally adjusted base allowances for Anglian and Bristol, both of which typically perform better than their peers on leakage reduction. At the FD, this adjustment is now only retained for Anglian. This is because when the CMA uses the most up-to-date data then Bristol is adequately funded for this outcome already.

- Enhancement funding: the CMA flagged in its PFs that it intended to do further work on the appropriate level of enhancement funding for leakage reduction. At the FD, the CMA has concluded its analysis, which has resulted in funding allowances for Anglian, Bristol and Yorkshire. The magnitude of these allowances will become clear when the CMA’s full report is published.

- Compliance risk: the CMA at the FD reverted the deadband levels for the compliance risk index back to Ofwat’s DD position. This is in contrast to the PFs where the CMA set the deadband levels using Ofwat’s FD position.

This will be updated with possible further changes once the full report is released.

Company concerns raised with ODIs and the CMA’s response

In PR19, most of the performance commitments (PCs) included in the FDs were accompanied by financial ODIs. These were designed by companies but amended by Ofwat. Some ODIs were symmetrical, whereas others were penalty-only. Some ODIs included caps on the level of outperformance rewards to protect customers, some included penalty collars to limit company risk, and some included deadbands. Ofwat’s approach to PCs and ODIs at PR19 included:

- assessing companies’ bespoke PC and ODI proposals;

- setting three common PCs on the basis of forecast UQ performance, with the remaining 12 common PCs set with reference to the ranges of anticipated performance included in companies’ business plans;

- setting a minimum reduction of 15% for leakage across the sector (itself a common PC);

- limiting any outperformance or underperformance ODIs to 3% gross return on regulated equity (RORE).

The CMA made adjustments to the Ofwat FDs of bespoke company PCs and ODIs in only a very limited number of cases. Indeed, the main points of contention raised by the companies concerned the common PCs and ODIs adopted by Ofwat, and its interventions at the FDs. The 15 common PCs were:

- the three UQ measures—supply interruptions, pollution incidents and internal sewer flooding;

- reducing water demand—leakage and per capita consumption;

- statutory measures—the compliance risk index (CRI) and treatment works compliance;

- asset health measures—mains repairs, unplanned outages, and sewer collapses;

- resilience measures—risks of sewer flooding in a storm, and severe restriction in a drought;

- vulnerability measures—the priority services register;

- customer experience—the customer measure of experience (C-MeX) and the developer services measure of experience (D-MeX).

The appellant companies advanced the following claims.

- There were difficulties in comparing companies on a like-for-like basis in a way that took adequate account of topographical differences.

- Ofwat had ignored the link between the service performance targets that were set and the increased costs of meeting these targets.

- Ofwat’s approach gave insufficient weight to each company’s own engagement with its customers.

However, the CMA argued as follows.

- Ofwat was right to intervene in company business plans to take account of comparisons between companies.

- There was no simple cost–service relationship whereby more demanding PCs should always be accompanied by higher allowed costs (although given the particularly stretching PC target for leakage, the CMA recognised the need for additional funding here—see below).

- While the extensive engagement undertaken by companies had gone a long way to reflect the specific priorities of customers, the CMA considered that there were limits to the weight that can or should be placed on customer research evidence in this area, as customers for example may have less information about comparators.

The CMA judged that the PC levels for the three common performance measures (the forecast UQ) were appropriate, although the collar for pollution incidents was increased in the case of Anglian, and the collar for internal sewer flooding was increased in the case of Yorkshire. Moreover, the CMA made adjustments to some of the other common PCs and ODIs.

- The CMA makes some adjustments to the ODI rates, caps, and collars for the common PCs relating to unplanned outages and mains repairs (with deadbands to limit downside exposure to factors that are outside companies’ control).

- For leakage, the CMA retained the 15% minimum PC commitment required by Ofwat in the FDs, but determined that some of the companies could require an additional allowance.

On this latter point, the CMA has concluded that there is a link between maintaining higher performance on leakage and costs—one that is not adequately compensated for in the base cost modelling for all companies. The CMA has therefore adjusted the base cost allowance for Anglian. In a departure from the PF the CMA now considers that Bristol is adequately funded already after the most recent data is included.

In addition, the CMA is minded to provide additional enhancement funding to Anglian, Bristol, and Yorkshire to achieve the future required level of performance.8

At the same time, it has removed enhanced ODIs for leakage (for all four appellant companies) and has amended the companies’ penalty rates for underperformance.

In sum, therefore, the CMA is in agreement with much of Ofwat’s overall approach to PCs and ODIs. However, the CMA has sought to reduce the risk exposure of the companies to certain limited aspects of the PC and ODI package. In addition, the CMA recognises that for at least three of the companies, attaining the ambitious leakage PCs will require further enhancement funding.

The CMA has largely endorsed Ofwat’s PR19 approach to assessing enhancement expenditure, but has made some amendments to individual assessments. The most material changes related to the CMA’s assessment of ‘deep dives’ (detailed, bottom-up assessments), where the CMA increased companies’ enhancement allowances by c. £75m relative to Ofwat’s PR19 determination. Two areas of enhancement expenditure received particular attention during the CMA appeal: enhancement to reduce leakage and enhancement to address the Water Industry National Environment Programme (WINEP).

1 CMA (2021), ‘Anglian Water Services Limited, Bristol Water plc, Northumbrian Water Limited and Yorkshire Water Services Limited Price Determinations, Summary of Final Determinations’, 17 March, para. 102.

2 Ibid., para. 7j.

3 Base costs represent operating expenditure and capital maintenance expenditure. Ofwat also modelled growth expenditure in its base cost models.

4 CMA (2021), ‘Water Redeterminations 2020: 2019/20 data for base cost models – Working Paper’, 13 January.

5 It is unclear from the summary whether Oxera’s guiding principles were adopted by the CMA for its final decision. We will comment on this further when the full decision is published.

6 CMA (2021), ‘Anglian Water Services Limited, Bristol Water plc, Northumbrian Water Limited and Yorkshire Water Services Limited price determinations: Summary of Final Determinations’, 17 March, para. 36.

7 Ibid., para. 56.

8 However, the net adjustment for Anglian was £1.2m for base expenditure and -£3.4m for enhancement expenditure, as the CMA had also removed other leakage-based allowances for Anglian (by dropping Ofwat’s alternative base cost models and Ofwat’s allowance of £71.4m for leakage enhancement expenditure).

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More