Company valuation in post-M&A disputes—the Mahtani v Atlas Mara ruling

Post-merger and acquisition (‘post-M&A’) disputes can take many different forms, such as breach of representations and warranties, fraud and misrepresentation claims, and post-completion breach of contractual obligations. This article discusses the valuation issues in a post-completion breach case based on the ruling handed down by the Hon Mr Justice Butcher at the UK High Court on 7 February 2024 on the Mahtani v Atlas Mara case.

The Mahtani v Atlas Mara case is a dispute between (i) Dr Rajan Lekhraj Mahtani (‘Dr Mahtani’) and others (the ‘Claimants’) and (ii) Atlas Mara (ATMA) and another (the ‘Defendants’). It concerns the Defendants’ acquisition of Finance Bank Zambia from the Claimants in June 2016 (the ‘Acquisition’).1

In his judgment, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher dismissed all claims by the Claimants, and assessed in detail the valuation of a Zambian building society that the Defendants acquired from the Claimants as part of the larger transaction.2

Oxera Partner, Dr Min Shi, CFA, was instructed by DLA Piper UK LLP, the solicitors for ATMA (the First Defendant), to act as ATMA’s valuation expert in this dispute.

The background of the dispute

ATMA is a financial services company founded in 2013 that operates in Sub-Saharan Africa. It was listed on the London Stock Exchange until 2021. At the time of the Acquisition, Finance Bank Zambia was a Zambian bank with several subsidiaries.

In this dispute, the Claimants alleged that ATMA breached certain terms of the sale and purchase agreement of the Acquisition (the ‘SPA’), and brought several claims against ATMA. One specific claim is the Building Society Claim, which relates to one of Finance Bank Zambia’s subsidiaries, i.e. Finance Building Society (‘FBS’), that ATMA acquired as part of the Acquisition.

At the time of the Acquisition, ATMA was not keen to purchase FBS. However, it was part of the sellers’ package, and Dr Mahtani was confident that he would be able to facilitate a sale of FBS from ATMA after the completion of the Acquisition. Against this backdrop, the SPA specified that certain escrow shares would be released to the Claimants if Dr Mahtani were to purchase, or procure a third party acceptable to the Defendants (acting in good faith) to purchase, FBS from ATMA by 31 December 2016.

On 20 December 2016, Dr Mahtani offered to purchase FBS for one Zambian Kwacha (‘ZMW’). This offer was not accepted by ATMA and no sale of FBS was completed by 31 December 2016. The Claimants alleged that ATMA’s refusal to accept Dr Mahtani’s offer was a breach of the SPA, which caused them to suffer substantial damages as it prevented them from realising substantial profits from a subsequent sale of FBS.

To quantify the Claimants’ alleged damages under this Claim, both sides’ valuation experts assessed the fair market value of FBS as at different valuation dates under the following two scenarios:

- the actual scenario, where FBS was owned and managed by ATMA;

- the counterfactual scenario, where Dr Mahtani would have purchased and managed FBS.

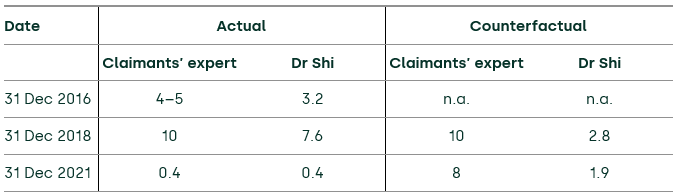

Both experts adopted the multiples method in their valuation assessment.3 Table 1 below summarises the Claimants’ expert and Dr Shi’s valuations of FBS at three valuation dates requested by the court.

Table 1 The Claimants’ expert and Dr Shi’s valuations of FBS (USD million)

In February 2023, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher issued his judgment and dismissed all claims brought by the Claimants. For the Building Society Claim, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher also assessed the Claimants’ expert and Dr Shi’s valuations of FBS in detail, and concluded that:4

where they disagreed, the approach and conclusions of Dr Shi were generally to be preferred, as her analysis was, in my view, superior and her approaches more realistic.

In reaching his conclusion, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher considered the following three questions.

- What are the relevant and appropriate comparators for valuing FBS in the actual scenario?

- What is the realistic and appropriate counterfactual scenario for valuing FBS under Dr Mahtani’s ownership and management?

- Are the valuation estimates supported by cross checks based on contemporaneous market data?

The relevant and appropriate comparators for valuing FBS in the actual scenario

The multiples method is based on the idea that two comparable companies ought to have similar valuation multiples (e.g. the price-to- earnings ratio). While both experts relied on the multiples method to value FBS, they differed in their opinion regarding the most relevant and appropriate comparators in the actual scenario.

In his analysis, the Claimants’ expert selected a set of comparable publicly listed companies, and used their valuation multiples to value FBS as at both 31 December 2016 and 31 December 2018.

In contrast, for the 31 December 2016 valuation date, Dr Shi started with the valuation multiples implied from the Acquisition, which reflected the contemporaneous assessment of the Defendants and the Claimants at the time of the Acquisition (i.e. 30 June 2016, which was close to the valuation date). She applied these multiples to FBS’s financial metrics as at end-2016, and made further adjustments to account for other contemporaneous factors affecting the value of FBS relative to that of Finance Bank Zambia as a whole.

After hearing both experts’ evidence, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher concluded that, for the 31 December 2016 valuation date:5

[Dr Shi’s] approach, which starts from an actual and recent arms’ length transaction, is more reliable than [the Claimants’ expert]’s reliance on a comparable companies method, especially as [the Claimants’ expert]’s comparable companies were selected for the original purpose of assessing the value of FBS as at 31 December 2018.

For the 31 December 2018 valuation date, Dr Shi valued FBS based on valuation multiples of a smaller set of comparable publicly listed companies that she considered to be more comparable to FBS than those relied on by the Claimants’ expert.

Dr Shi also assessed the offers from third parties for purchasing FBS in 2018. Given that none of the offers led to the sale of FBS, Dr Shi considered that the offered amounts were not reliable indications of the value of FBS as at 31 December 2018.

In his judgment, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher agreed with Dr Shi’s analysis, and concluded that:6

I accepted her evidence [regarding the number of the comparable companies] that ‘it is not the more the better’.

[N]one of the offers [received by ATMA in 2018 from third parties for purchasing FBS] proceeded to a transaction, and Dr Shi gave cogent evidence as to why the offers were not reliable indications of FBS’s value as at 31 December 2018.

The realistic and appropriate counterfactual scenario

For the valuation of FBS in the counterfactual scenario, both experts relied on the price-to-earnings multiples of comparable companies.7 However, the experts differed in their assumptions regarding FBS’s level of costs in the counterfactual scenario, which led them to arrive at significantly different estimates of earnings and valuation for FBS.

Specifically, the Claimants’ expert assumed that the level of FBS’s costs in the counterfactual scenario would have been the same as in the actual scenario—which was particularly low, as FBS was part of a larger financial institution (i.e. the ATMA group) and enjoyed significant cost savings thereof in the actual scenario.

In contrast, Dr Shi assumed that FBS would have operated as an independent entity had Dr Mahtani purchased FBS from ATMA, and estimated the level of FBS’s costs in the counterfactual scenario based on the average cost-to-income ratio of Zambian banks. Under this approach, Dr Shi arrived at much lower valuation of FBS as at 31 December 2018 in the counterfactual scenario.

After hearing both experts’ evidence and considering the factual evidence in relation to the Claimants’ pleaded case, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher concluded that:8

[The Claimants’ expert’s assumption] depends on saying that FBS could and would have been operated as part of a wider group, but it was unpleaded and not properly evidenced that this would have occurred.

In the absence of it being established that, in the counterfactual, FBS could have had a lower cost to income ratio [than an average bank in Zambia], [Dr Shi’s approach] is a reasonable approach.

For the 31 December 2021 valuation date, Dr Shi applied a similar approach as the one discussed above to forecast FBS’s counterfactual financial performance during 2019–21. Again, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher considered Dr Shi’s approach ‘to be a reasonable approach’.9

The cross checks

In reaching his conclusion regarding the valuation of FBS in the counterfactual scenario, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher also considered the cross checks based on the contemporaneous market data.

Specifically, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher compared (i) the experts’ valuation estimates as at end-2018 and 2021 with (ii) the valuation estimates implied from FBS’s value in 2016 and the movements of the value of comparable companies and the relevant equity markets during 2016–21. Based on the evidence presented in Dr Shi’s expert report, the Hon Mr Justice Butcher concluded that:10

This would have produced a figure [as at end 2018] in the same region as that under Dr Shi’s approach based on average costs.

[Dr Shi’s estimate as at end-2021] may be cross-checked against another approach, of taking the change in the market value of comparable companies from 31 December 2016 to 31 December 2021 […] I consider that to support the reasonableness of the valuation of [Dr Shi].

Lessons for valuation experts

This case offers several important lessons for valuation experts.

The first is that the fair market value of a company corresponds to the price in a hypothetical arm’s length transaction between a willing buyer and a willing seller. If the company being valued was recently involved in an actual and arm’s length transaction, the valuation implied from such a transaction may provide the most direct and relevant contemporaneous evidence on the company’s fair market value. In the current case, as FBS was part of an actual transaction that took place shortly before the first valuation date, the implied value from the transaction serves as a good starting point for valuing FBS.

Second, the valuation estimates implied from offers that did not lead to actual transactions may not provide reliable indications of the fair market value. This is because offers may be made by potential buyers who do not have complete information about the company (e.g. they may be made before a full due diligence), or by potential buyers who do not have sufficient funding and resource to complete the transaction.

Third, when valuing the company in the counterfactual scenario, the assumptions adopted by the valuation expert should be realistic and consistent with the contemporaneous evidence. In the current case, there was no evidence suggesting that FBS would have continued to be part of a much larger financial group to enjoy the cost savings thereof. This means that it was inappropriate to reflect such cost savings when valuing FBS in the counterfactual scenario.

Finally, where possible, the valuation experts should cross-check their estimates against contemporaneous market data and evidence, and/or the estimates from other reasonable approaches. This would help the valuation experts to identify and correct any issues in relation to their analyses and make their expert evidence more credible.

Footnotes

1 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm).

2 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), paras 219–229 and 244.

3 The only exception is for the 31 December 2021 valuation date under the actual scenario, for which both experts relied on the net book value of FBS, as it had ceased operation as a standalone entity by then.

4 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), para. 224.

5 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), para. 225.

6 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), para. 226.

7 Besides the price-to-earnings multiple, both experts also used the price-to-book multiples of comparable companies to value FBS. In addition, the Claimants’ expert used the price-to-revenue multiple in his analysis.

8 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), para. 227.

9 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), para. 229.

10 Mahtani & Others v Atlas Mara Limited & Another [2024] EWHC 218 (Comm), paras 227 and 229.

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More