Competition between airports in Europe soars… but where next for regulation?

Where airports do not face effective competition, it may be necessary to introduce economic regulation to protect passengers’ interests. Regulation can help to ensure fair prices, sufficient investment, high-quality service, and efficient costs. At the same time, it is important that regulatory interventions are targeted at areas where competition will not deliver the desired outcomes. With increasing competition between airports, what tools are available to help policymakers decide whether regulation is required?

The 2009 Airport Charges Directive (ACD) established a common European framework for regulating elements of airport charges, airports’ operations and their interactions with users. Any airport with more than 5m passengers per annum (mppa) is covered by the ACD, as is the largest airport in each EU member state. In many cases, these airports are often covered by additional price and service-quality regulations imposed by their national regulators.

In the decade since the ACD was introduced, there has been a significant increase in competition between airports.1 Airports compete for passengers, both with airports in their local catchment areas and with airports further afield for transfer passengers, and also more widely for airline business. Regulators and government bodies have acknowledged that effective competition can deliver significant benefits;2 the European Commission stated that there is no need for regulation if airports are subject to such competition.3 However, the ACD considers size rather than market power as the determining factor of whether an airport should be regulated.

Oxera, in partnership with CMS Belgium, undertook analysis on behalf of Airports Council International (ACI) Europe to identify the most appropriate approach to determining whether airports should be regulated.4 Over the past year, we have been engaging with the Thessaloniki Forum, a group of European aviation regulators, on our proposed process.5 In November 2018, the Forum published a paper proposing the use of criteria to distinguish airports that may have significant market power (SMP) from those that do not—the objective being to inform decisions about undertaking SMP assessments, and to decide on appropriate economic regulation.6 These proposals take account of many of the elements of the framework developed by Oxera and CMS Belgium for ACI Europe. This article sets out the main features of this framework.

Determining whether to regulate

One way to determine whether it is appropriate to apply regulatory intervention to airports is by undertaking an analysis of significant market power (SMP), as applied in other regulated sectors and consistent with the concept of dominance in competition law. This is the approach adopted by the European Commission in a number of other sectors. For example, in the electronics communications sector, the Commission sets out three cumulative criteria to determine whether a market ‘is susceptible to ex ante regulation’.7 National regulators must then review the markets susceptible to ex ante regulation to determine whether there are firms with SMP in these markets. Only where firms do have SMP do these markets become subject to regulation.

The Commission has stated that, in this respect, its objective is to ‘[limit] the number of markets within the electronic communications sector where ex ante regulatory obligations are imposed’.8

SMP assessments can be detailed and resource-intensive exercises that take many months to complete. Therefore, if a market power test were to be used to determine whether to apply the ACD, it would need to take account of two factors:

- that airports representing just under 80% of EU passenger traffic fall within the scope of the Directive;[9]

- that these airports, and their regulators, are of very different sizes, face different market conditions, and have different capacities.

Proposed process

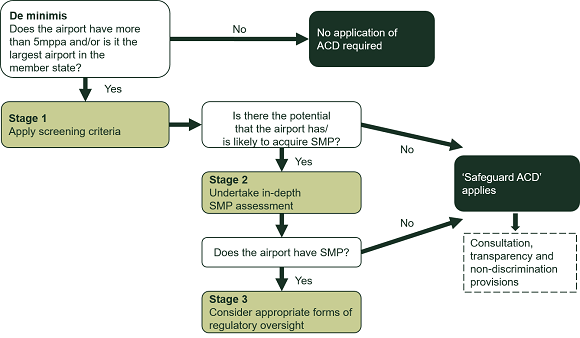

Taking account of these factors, we have proposed a process for implementing SMP assessments for European airports. The process, which involves a two-stage SMP test followed by a remedies stage, is a practical way for member states to determine which airports face effective competition and can therefore be subject to reduced levels of regulatory intervention, while also regulating where required to protect consumers against SMP. The process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Proposed two-stage SMP and remedies process

Stage 1: screening criteria

SMP assessments can impose a significant burden, and the ACD covers approximately 80 airports. Therefore, a relevant first consideration is to look at the factors that are typically examined as part of an SMP assessment and also able to be analysed with limited data and resources. This can help to determine whether a more detailed SMP assessment is required.

We have established ‘screening criteria’ as initial indications of whether an operator could have and/or is likely to acquire SMP. They are not a ‘full’ competition assessment, and a detailed SMP assessment would take into account a number of additional factors. Rather, the stage 1 criteria have been developed so that they can be applied easily (e.g. based on readily available data) and objectively (e.g. based on numerical cut-offs).

As these criteria are necessarily high-level, they need to be set on a conservative basis. In other words, the application of the screening criteria should minimise the possibility that an operator with SMP would be found not to have market power at this stage in the process—i.e. stage 1 would aim to minimise false negatives. The screening criteria are therefore intended only to identify the potential for an airport to have or acquire SMP, not to confirm the existence of SMP. An airport needs to meet all the criteria in order for it to be determined that it does not have SMP. As the Thessaloniki Forum notes, any one criterion may be sufficient in isolation, and therefore having multiple criteria represents a conservative approach.10

If it is determined at this stage that an operator potentially has SMP, a more detailed assessment in stage 2 determines whether this is in fact the case. At the same time, it is important to ensure that the more detailed stage 2 assessments are not undertaken across all airports. Therefore, the criteria, and the thresholds at which they are applied, need to be reasonable.

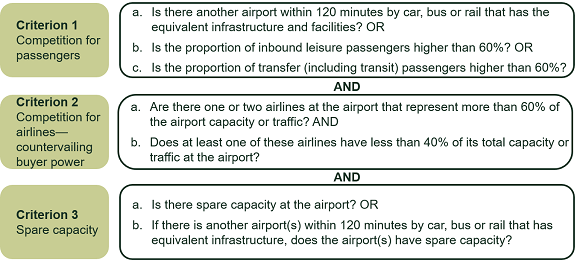

Figure 2 sets out the stage 1 screening criteria that could be included by the Commission in a revised ACD. The criteria are based on elements that would typically be considered as part of an SMP assessment, to determine whether airports are subject to effective competition.

Figure 2 Screening criteria

Criterion 1: competition for passengers

This reflects the ways in which airports compete for passengers, which in turn can influence competition between airports for airlines. Various factors are incorporated into this criterion through three sub-conditions, applied as ‘or’ conditions. Therefore, only one of the three conditions needs to be met in order for the airport to be determined to meet criterion 1. We consider that this is appropriate since individual airports will face different competitive constraints depending on their circumstances.

Criterion 2: competition for airlines—countervailing buyer power

In some cases, an airport may have a degree of market power, but it may be mitigated by the countervailing buyer power of airlines. If an airline(s) represents a large share of the airport’s traffic, and if in response to a price increase the airline(s) can shift at least some capacity away from the airport, a price increase may not be profitable.

Buyer power is more likely to play a significant role at airports where a small number of airlines make up the majority of capacity. This is because the switching of just some of the aircraft of one (or a few) airlines could have a significant effect on the airport’s profitability. Therefore, switching—or even just the credible threat of switching some capacity away from the airport—may be sufficient to constrain the behaviour of the airport.

At the same time, if one airline has most of its capacity at an airport, it may be that the airline is dependent on the airport. This does not mean that the airline is unable to switch, but it may be less likely to do so than an airline that has multiple bases. Therefore, it is also important to consider the co-dependence of airlines on airports as part of this criterion by looking at the proportion of an airline’s overall business that is at the airport.

Criterion 3: spare capacity

While congestion at an airport is not necessarily an indicator of market power, if an airport is capacity-constrained, it may have reduced incentives to compete strongly with other airports. The bargaining power of airlines may also be weakened, as there are other airlines willing to serve that airport if current airlines leave.

The extent to which capacity constraints affect competition also depends on the capacity constraints at other airports to which airlines and/or passengers could switch. For example, if a given airport is capacity-constrained, but there are other airports in the catchment area with spare capacity, then airlines and/or passengers may be able to switch. In contrast, if other airports in the catchment area are also capacity-constrained, airlines and passengers may be less able to switch.

Therefore, in cases where an airport passes criterion 1 solely because there is another airport in its catchment area (i.e. condition 1a), either the focal airport needs to have spare capacity or the other airport in the catchment area needs to have spare capacity in order to pass this criterion (i.e. an airport needs to meet either criterion 3a or 3b).

However, as noted above, passengers and airlines do not just consider airports in a particular local catchment area when deciding which airport to use. If there is no other airport within the catchment area, the focal airport would have passed criterion 1 because it competes for transfer traffic or inbound leisure traffic. In this case, it would not be practical to consider the capacity constraints of all competing airports, and at least one of these airports is likely to have capacity available. However, there may be some origin and destination passengers who would only be willing to travel to/from this city. Therefore, the focal airport itself needs to have capacity available—i.e. condition 3a needs to be met and 3b does not apply.

Stage 2: SMP assessment

If an airport meets all the screening criteria in stage 1, it is unlikely to have or acquire SMP, and a detailed assessment as part of stage 2 is not necessary. Conversely, if the airport does not meet all of the criteria, the existence or absence of SMP cannot be definitively determined based on these criteria alone and a more detailed SMP assessment would be necessary to determine whether: (i) the airport does not have and is unlikely to acquire SMP; or (ii) the airport has or is likely to acquire SMP.

SMP assessments can be quite detailed exercises. While various documents provide guidance on how to undertake these assessments and the factors to take into account, these tend to be general guidelines or specific to individual sectors, not for the airport sector per se.

We have set out proposed SMP assessment guidelines, which draw on the Commission’s guidance and decision-making practice but are specific to the airport sector. These guidelines are intended to provide regulators, airports and other stakeholders with an overview of the steps of an SMP assessment and the analysis needed to determine whether an airport has the ability to ‘behave to an appreciable extent independently of competitors, its customers and ultimately of consumers’.11

Stage 3: determine the appropriate form of economic regulatory oversight

If there is a finding of SMP at stage 2, the assessment proceeds to stage 3. As part of stage 3, the national regulatory authority undertakes an assessment of whether any additional regulatory oversight is appropriate, and if so the form of this regulatory oversight.

The Thessaloniki Forum has proposed using regulatory criteria, in addition to screening criteria, to inform a decision about whether to impose economic regulation and in what form. These regulatory criteria are intended to be between screening criteria and a full SMP assessment in terms of complexity and burden, although the Forum notes that ‘relying on regulatory criteria rather than a MPA [market power assessment] would result in a less robust assessment about the degree of market power of the airport.’12 As a result, the remedy could lead to too much or too little regulation. We do not consider this a viable alternative to an SMP assessment as the risk of sub-optimal decision-making is too high.

We also do not consider that this is appropriate in determining the form of regulation at the airport. This is because the outcome of the regulatory criteria is binary—i.e. it determines that an airport has SMP or that it does not. However, there remains a question about the degree of market power held by the airport. There may also be evidence that points in different directions. Therefore, the balance of evidence needs to be weighed in the round when deciding on the appropriate form of regulatory oversight. Broadly, it would be expected that the greater the competitive constraints, the lower the extent of regulatory intervention in decision-making.

Conclusion

In 2017, the European Commission conducted an evaluation of the ACD to determine whether it had achieved its objectives and to ‘assess to what extent EU regulation of airport charges as foreseen by the Directive is still relevant to the current needs.’13 The evaluation was also meant to consider the role of SMP assessments, as set out in the Commission’s Aviation Strategy.14 The Commission has noted that:15

The evaluation is aimed to provide not only an up-to-date overview of the application of the Directive in the member states and to enquire into the benefits it delivered, but should seek to identify areas of concern in its implementation (if any), based on existing evidence and taking into account the current market reality.

As identified in our 2017 report, which covers the period from the time the ACD was implemented across member states, there has been a significant increase in competition at European airports, particularly for those with more than 5m passengers.15 Therefore, the market reality is quite different from what existed at the time when the Directive was introduced.

Overall, our proposed approach to SMP testing and remedy design could be used in a revised ACD to assist in fostering the continuing development of airport competition and ensuring that regulation is applied only where needed and in a manner proportionate to the degree of market power. It also provides a practical process that balances simplicity and reliability, which should make the application of market power tests tractable for individual national regulators while maintaining a common framework of principles and safeguards for the protection of passengers at a European level.

1 See, for example, Oxera (2017), ‘The continuing development of airport competition in Europe’, September.

2 See, for example, Civil Aviation Authority (2015), ‘Guidance on the Application of the CAA’s Competition Powers’, CAP 1235; Department of Transport, Tourism and Sport (2017), ‘National Policy Statement on Airport Charges Regulation.’

3 European Commission (2015), ‘An Aviation Strategy for Europe’.

4 Annabelle Lepièce and Hanne Baeyens from CMS Belgium assisted in the legal assessment of the study. The full report can be found at: Oxera and CMS (2017), ‘Market power assessments in the European airports sector’, prepared for ACI Europe, 17 November.

5 The Thessaloniki Forum was tasked by the European Commission to make recommendations for how the ACD could be implemented more effectively.

6 Thessaloniki Forum of Airport Charges Regulators (2018), ‘The Use of Selective Criteria in the Economic Regulation of Airports’, November.

7 European Commission (2014), ‘Commission Recommendation on relevant product and service markets within the electronic communications sector susceptible to ex ante regulation in accordance with Directive 2002/12/EC’, 9 October.

8 European Commission (2014) ‘Commission Recommendation on relevant product and service markets within the electronic communications sector susceptible to ex ante regulation in accordance with Directive 2002/12/EC’, 9 October.

9 As at 1 September 2016. European Commission (2016), ‘Evaluation of the Directive 2009/12/EC on Airport Charges’, 1 September.

10 Thessaloniki Forum of Airport Charges Regulators (2018), ‘The Use of Selective Criteria in the Economic Regulation of Airports’, November, para. 5.10.

11 Case 27/76, United Brands v Commission.

12 Thessaloniki Forum of Airport Charges Regulators (2018), ‘The Use of Selective Criteria in the Economic Regulation of Airports’, November, para. 4.13.

13 European Commission (2016), ‘Evaluation of the Directive 2009/12/EC on Airport Charges’.

14 European Commission (2015), ‘An Aviation Strategy for Europe’.

15 Oxera (2017), ‘The continuing development of airport competition in Europe’.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More