Conduct risk management—high five?

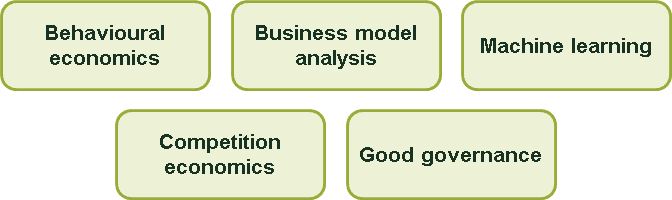

Financial services providers around Europe are subject to clear expectations from regulators regarding conduct risk (or ‘the risk of misconduct’ that can cause poor consumer outcomes or undermine market stability or competition). What are these expectations, and how can providers meet them? In our experience, managing conduct risk requires a new toolkit based on behavioural economics, business model analysis, machine learning, competition economics, and good governance.

The past five years or so have seen a profound shift towards outcomes-based regulation of financial services. Rather than ‘just’ complying with a prescribed set of rules, providers are being encouraged to think about what outcomes they want to achieve for their consumers, and how best to deliver them.1 However, it is important to recognise that the regulators are on a journey, developing their understanding of what it means to focus on outcomes.

What are the regulatory expectations?

In a speech earlier this year, Andrew Bailey, Chief Executive of the UK Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), stated that:2

Rules are a crucial mechanism for delivering outcomes, but can also be interpreted so rigidly as to become a box-ticking exercise. This is a lesson we want to see reflected in firm behaviour – any organisation that prioritises being within the rules over doing the right thing, will not stand up to scrutiny for long.

In implementing outcomes-based regulation, regulators are turning towards conduct risk frameworks, encouraging firms to create their own frameworks and thus be on the front foot when managing conduct risk. Regulators have set out the high-level factors that such frameworks must consider, and many firms, in our experience, have formulated effective frameworks.

Firms can get caught out when regulators drill down into the specific detail of the consumer outcomes delivered by the firm. Responding to this challenge requires a new toolkit of behavioural economics, business model analysis, machine learning, competition economics, and good governance. Furthermore, firms are required to embed this toolkit into their organisations and not just to rely on ‘tick-box’ compliance.

In May 2019, the FCA concluded that:3

Many firms have made significant strides in improving their policies, processes, training and identification of conduct risk. However, overall progress or embedding in some cases has been patchy or in danger of stalling.

Similarly, in July 2019, the European Banking Authority (EBA) stated that:4

In many instances, the responses provided by manufacturers suggested that, in a large number of cases, the interests of the consumers, although taken into account at a high level, did not quite attract the same attention as compliance with prudential requirements. In other words, while the manufacturers surveyed had implemented the required processes, this was not necessarily done in a way that put the necessary focus on ensuring that consumers’ needs are met.

Below, we briefly explore the latest conduct risk frameworks designed by the EBA, the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) and the FCA, before exploring what tools providers need in order to operationalise these frameworks.

EBA ‘Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance’

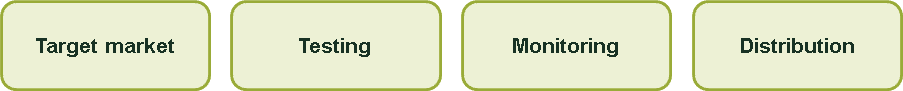

The EBA published its ‘Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance’ in 2015, and published an updated report on these in July 2019.5 The EBA focuses on four pillars: identifying the target market; product testing; product monitoring; and the distribution process (see the figure below).

Figure 1 The four pillars of the EBA’s ‘Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance’

For example, the guidelines make clear that defining the target market is a key step in product design, and that it must be carefully defined to be ‘appropriate for the interests, objectives and characteristics of the identified target market’.6 Thus the product manufacturer must go beyond simplistic demographics in defining the target market; it must carry out detailed customer segmentation.

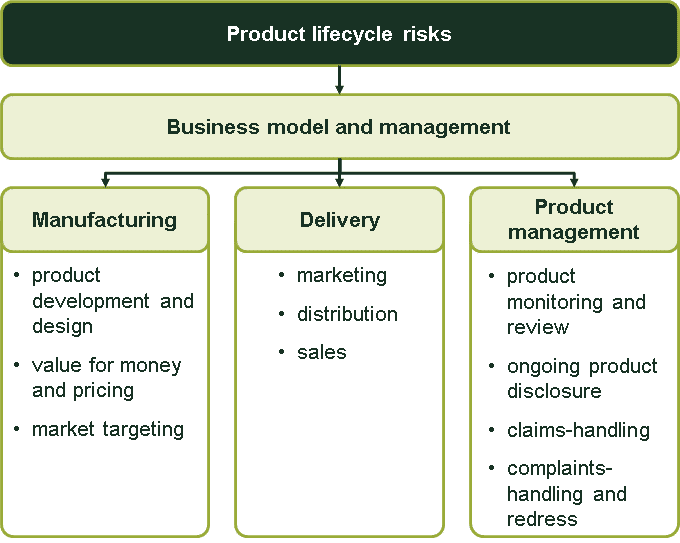

EIOPA’s ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk through the Product Lifecycle’

In 2019, EIOPA published its ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk through the Product Lifecycle’, in which it notes that:7

Conduct risks arise in the context of consumer and firm behaviours that are constrained in ways that traditional economic analysis did not fully grasp […].

For example, EIOPA states that product testing must consider insights from behavioural economics:8

Appropriate testing of insurance products should take into consideration consumers biases (e.g., over confident target market), attitudes, and behaviours […].

Figure 2 EIOPA’s framework for assessing conduct risk through the product lifecycle

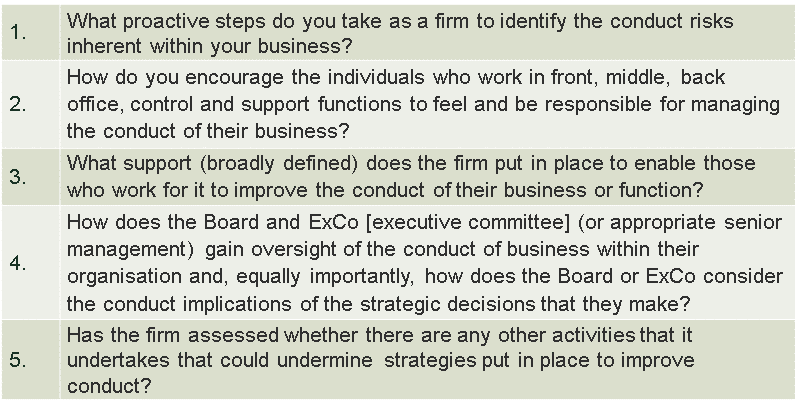

The FCA’s ‘5 Conduct Questions’

The 5 Conduct Questions, as listed in the table below, provide the high-level basis for the FCA’s supervisors to assess a firm’s conduct risk management. While the FCA began using these questions in the supervision of wholesale banking, we have observed the FCA using them across a variety of financial services markets.9

Table 1 The 5 Conduct Questions

These high-level questions begin to unpick how providers identify and control conduct risk. Importantly, the questions also assess whether Boards have sufficient oversight of their firm’s conduct (through management information, for example) and are comfortable with the trade-offs being made in managing the conduct.

However, it is not as simple as answering the FCA’s 5 Conduct Questions alone. The questions are sufficiently broad and principles-based that they can apply to many manifestations of conduct risk. For example, providers must also demonstrate that they are treating their customers fairly (see box below); in practice, this means that they must analyse the full distribution of consumer outcomes.

Treating customers fairly

While conduct risk covers an extremely broad spectrum and is highly complex, the Treating Customers Fairly (TCF) outcomes comprise an important component. The FCA’s predecessor (the Financial Services Authority, FSA) produced a discussion paper on TCF outcomes 15 years ago. In its subsequent progress report of July 2006,1 the FSA listed a number of TCF outcomes it aimed to achieve for retail customers. These six outcomes remain the same in the FCA’s more recent guidance from 2015 and 2019.2

• Outcome 1: Consumers can be confident they are dealing with firms where the fair treatment of customers is central to the corporate culture.

•Outcome 2: Products and services marketed and sold in the retail market are designed to meet the needs of identified consumer groups and are targeted accordingly.

•Outcome 3: Consumers are provided with clear information and are kept appropriately informed before, during and after the point of sale.

•Outcome 4: Where consumers receive advice, the advice is suitable and takes account of their circumstances.

•Outcome 5: Consumers are provided with products that perform as firms have led them to expect, and the associated service is of an acceptable standard and as they have been led to expect.

•Outcome 6: Consumers do not face unreasonable post-sale barriers imposed by firms to change product, switch provider, submit a claim or make a complaint.

Notes: 1 Financial Services Authority (2006), ‘Treating customers fairly – towards fair outcomes for consumers’, July. 2 Financial Conduct Authority (2015), ‘Fair treatment of customers’, 12 May. Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘Consumer credit – Treating customers fairly’, 23 April.

Source: Oxera.

How can providers meet these regulatory expectations?

Across the different conduct risk frameworks, the common denominator is the tools and skills required to manage conduct risk. These are shown in the figure below.

Figure 3 Tools to manage conduct risk

Behavioural economics

Behavioural economics uses insights from psychology to explain the effects of cognitive and behavioural processes on consumer behaviour and market outcomes.10 Providers and regulatory bodies have increasingly turned to behavioural economics when exploring perceived problems in consumer markets, and in designing remedies aimed at improving outcomes.

For example, EIOPA has stated that:11

Positive consumer outcomes are at risk when products are designed to deliberately take advantage of demand side biases or human behaviour.

[…]

Sophisticated Big Data analytical tools can also be used to take advantage of behavioural biases, raising concerns from an ethical perspective. For instance, customers identified as less likely to complain, switch products and shop around or less sensitive to pricing, may obtain less favourable terms and conditions or be offered more expensive products.

Furthermore, the EBA recognises the importance of customer research:12

Manufacturers have set up processes and steps to identify whether a product meets the interests, objectives and characteristics of the target market, but the approach followed is not always clear, suggesting that further clarity may be beneficial. Most seem to carry out some form of customer research, but such research is often more focused on marketing or the commercial interests of the manufacturer than on customers’ needs.

Providers can use behavioural economics to achieve the following.

- Identification of the biases driving customers’ behaviour. This will help to mitigate conduct risks in the design of products, communications and advice.13

- Review and test customer communications. This will reveal where biases are being triggered and whether these can lead to poor outcomes. It is often in communication and engagement where things go wrong. For example, FCA enforcement cases and Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) decisions have ruled against firms offering products that arguably could provide good consumer value, but which were not properly communicated to consumers.14

- Definition of what each product is for. It is important to be clear internally and externally about the purpose of a product. Understanding how consumers will use a product helps to inform the outcomes the firm expects to see. Getting product, marketing and other teams around the same table can be highly illuminating; inconsistencies between them can lead to discrepancies in how a product is designed and marketed, which can result in poor consumer outcomes.

Business model analysis

Business model analysis explores whether the interests of the consumer and provider are aligned.15 One can expect that the commercial returns to the provider should arise predominantly from consumer outcomes that are consistent with the core purpose of the product (i.e. good consumer outcomes).

Any misalignment can lead to conduct risk. With hindsight, misalignment of business and consumer interests often seems obvious—such as with banks selling payment protection insurance to people not in employment (and therefore unable to claim). In practice, however, the inappropriate use of products can continue unchallenged if the core purpose has not been well defined. For example, the FCA found that many overdraft customers used overdrafts to provide credit over long periods, which might not be the most appropriate form of borrowing for them.16

Having segmented the customer base—for example, according to customer behaviour and product usage—business model analysis will highlight the range of consumer outcomes and where profits are generated, and also what type of consumer and consumer behaviour the business model may be relying on. This is the first step in assessing the sustainability of the business model and fairness of consumer outcomes.

Machine learning

It is important to understand the full distribution of consumer outcomes. There are various ways to segment consumers—for example, according to behaviours, characteristics or vulnerability. Regulators and firms may use cluster analysis (with the benefit of machine learning, a form of ‘artificial intelligence’), which allows them to quickly analyse large amounts of data to assess the behaviour of different customer segments.

The FCA’s analysis of bank overdrafts used a clustering approach to identify customer groups that were not using the product as intended, resulting in bad consumer outcomes.17 This led to regulation and the banning of unarranged overdrafts. The process is not based on predetermined thresholds or rules; rather, the data itself identifies cohorts that exist within the population of customers. Having identified clusters, providers can start to describe them and see how outcomes differ for different parts of their customer base.

Providers should, however, be careful to ensure that there is effective governance of complex machine-learning algorithms in pricing models.

Competition economics

It is important to consider the options that customers may or may not have, thereby avoiding the exploitation of customers with limited choice. There are several aspects to this, including that providers should not act to restrict the choice of consumers without good reason. This does not mean that a firm cannot limit the availability of new-customer discounts to existing customers, for example, but it would need to be confident that sufficient choice exists for consumers to shop around for the best deal.18

More broadly, understanding the market dynamics and the degree and nature of competition in the market inform the management of conduct risks. For example, in the payday loans market, understanding the product dimensions upon which providers competed informed the FCA’s findings.19

Good governance

Historically, firms have relied heavily upon the ‘three lines of defence’ model to comply with their regulatory requirements (i.e. risk, compliance and audit). While it is undoubtedly important to have such checks and balances in place, conduct risk clearly crosses multiple business functions, and prevails across the entire organisation. The old ‘tick-box’ methods and frameworks no longer suffice.

In our experience, Boards of Directors with a responsibility to both regulators and shareholders (and wider stakeholders) can find it difficult to adapt to the new regulatory approach or to devote sufficient time to conduct risk oversight in addition to their other corporate duties.20 In particular, they can find it challenging to balance the shareholders’ desires of driving a profit-focused culture, centred on increasingly short-term results, and a more customer-centric model with reduced risks.

The regulatory expectations (both by the FCA and EU regulators as per EU Directives)21 are that firms will have an appropriate product governance framework, including product-focused committees, and that senior manager functions were involved in all stages of the decision-making process. Committees and Board of Directors should be provided with relevant management information to assist in effective product governance.

Good governance includes the following.

- Developing a framework for assessing fairness. Fairness is a subjective matter. Enabling sensible discussion by the Board requires a clear framework within which the outcomes can be reviewed from both business and consumer perspectives using the right metrics. These perspectives may be conflicting, but they are worth calling out given that trade-offs are inevitable.

- Developing insightful MI dashboards. Boards need the latest figures to be able to monitor consumer outcomes. Therefore, metrics must be developed that capture the distribution of outcomes, rather than just the average, across the customer base and over time.

- Clarify responsibilities and accountability. Greater emphasis on both individual accountability and corporate accountability—for example, through the Senior Managers & Certification Regime (SM&CR) in the UK—is adding pressure to minimalise any exposure to the wide-ranging holistic regulatory agenda. For example, the SM&CR aims to make staff working for financial services providers ‘more accountable for their conduct and competence’.22

Conclusions

Financial services providers in the EU are subject to clear expectations from regulators regarding conduct risk. The development of appropriate conduct risk frameworks is essential, as is having appropriate governance and senior management arrangements. The skills listed above are crucial for implementing these frameworks; providers can effectively use these tools to mitigate conduct risk.

Going forward, regulators are likely to focus increasingly on whether providers are managing the conduct risks around the greater use of big data and artificial intelligence throughout the product lifecycle.23 Providers will find themselves using the tools listed above in ways that are ever-more sophisticated. Further, EIOPA has highlighted the need for ‘auditability and explainability’ of artificial intelligence, hinting that providers will find themselves using the tools listed above in ever-more sophisticated ways.24

1 See, for example, Oxera (2019), ‘Fair ground: a practical framework for assessing fairness’, Agenda, March.

2 Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘Andrew Bailey speech at the Annual Public Meeting 2019’, 17 July.

3 Financial Conduct Authority (2019), ‘“Progress and challenges” 5 Conduct Questions, Industry Feedback for 2018/19 Wholesale Banking Supervision’, May, p. 3.

4 European Banking Authority (2019), ‘EBA Report on the Application of the Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance (POG) arrangements’, EBA/GL/2015/18, 5 July, para. 17.

5 European Banking Authority (2019), ‘EBA Report on the Application of the Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance (POG) arrangements’, EBA/GL/2015/18, 5 July, para. 17. European Banking Authority (2016), ‘Guidelines on product oversight and governance arrangements for retail banking products’, para. 3.2.

6 European Banking Authority (2015), ‘Guidelines on product oversight and governance arrangements for retail banking products’, para. 3.2.

7 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2019), ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk through the Product Lifecycle’, p. 5.

8 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2019), ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk through the Product Lifecycle’, p. 14.

9 Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘“5 Conduct Questions” Industry Feedback for 2016 Wholesale Banking Supervision’, April.

10 Oxera (2015), ‘Behavioural economics, competition and remedy design (revisited)’, Agenda, April.

11 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2019), ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk Through The Product Lifecycle’, p. 15.

12 European Banking Authority (2019), ‘EBA Report on the Application of the Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance (POG) Arrangements’, EBA/GL/2015/18, 5 July, para. 55.

13 UK Finance (2019), ‘Behavioural economics: making an impact’, March.

14 For example, Financial Conduct Authority (2014), ‘Financial Conduct Authority fines Credit Suisse and Yorkshire Building Society for financial promotions failures’, press release, 16 June. For example, Financial Ombudsman Service (2018), ‘Paying the price?’, Ombudsman News, Issue 144, April.

15 Oxera (2017), ‘Should we be cross about cross-subsidies? Experience from the financial services sector’, Agenda, March.

16 Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘High-Cost Credit Review: Overdrafts consultation paper and policy statement’, December, CP18/42.

17 Oxera (2019), ‘Big data and AI: risks and opportunities for insurers’, Agenda, 19 September.

18 Oxera (2019), ‘Fair ground: a practical framework for assessing fairness’, Agenda, March.

19 Financial Conduct Authority (2018), ‘High-Cost Credit Review: Overdrafts consultation paper and policy statement’, December, CP18/42.

20 For a wider discussion on responsibility to various stakeholders, see https://www.oxera.com/beyond-the-bottom-line/

21 See MiFID Directive; Insurance Distribution Directive; EIOPA (2019), ‘Framework for Assessing Conduct Risk through the Product Lifecycle’; and European Banking Authority (2019), ‘EBA Report on the Application of the Guidelines on Product Oversight and Governance (POG) Arrangements (EBA/GL/2015/18), 5 July.

22 Financial Conduct Authority (2015), ‘Senior Managers and Certification Regime’, 7 July, last updated 9 December 2019.

23 Oxera (2019), ‘Big data and AI: risks and opportunities for insurers’, Agenda, 19 September.

24 European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (2019), ‘Big data analytics in motor and health insurance: a thematic review’, April.

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More