Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the potential for unintended consequences. Below, we explore the range of approaches used in the UK and EU.

Introduction

When applying CBA to public policy decisions, problems that can arise include: (i) unexpected behavioural responses from diverse stakeholders (including different categories of consumer); (ii) complex distributional effects (perhaps requiring the application of different weights to the various group interests); (iii) the valuation of non-market services and intangible effects. Even when analysed retrospectively, it can be difficult to separate out the additionality of an implemented policy. Given these difficulties, there have been recent initiatives to provide guidance on applying CBA to public policy decisions .

In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has produced CBA guidelines, while the Payment Systems Regulator (PSR) has published a CBA policy for consultation. In the EU, policy appraisal is instead favouring multi-criteria analysis1 (MCA). CBA of public policy are often conducted in the context of a regulatory impact assessment (RIA)—below, this will be discussed further to discern how CBA can be effectively used to support public policy decisions.

Regulatory impact assessments (RIAs)

Policy changes have both intended and unintended changes on a range of stakeholders, and it is natural to assess their impact before implementation to lower the risk of unexpected negative effects on stakeholders , especially those who are least able to cope with adverse consequences. RIAs achieve this by following a logical process, summarised in eight steps:

- defining the problem that requires intervention;

- confirming the objectives of the policy change to resolve the problem;

- reviewing the range of considered policy options;

- identifying the affected stakeholders;

- analysing the impact on the affected stakeholders;

- conducting distributional analysis where there is an uneven stakeholder impact;

- consultation on contentious issues;

- preparing monitoring and evaluation plans.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is also a strong advocate of RIA. In 2012,2 the OECD noted that a well-functioning regulatory framework is essential for restoring growth (a key UK government objective) and more recently proposed3 a set of principles for an RIA, including a six-step guide.4 CBA are vital tools for developing well-functioning regulatory frameworks and robust impact assessments.

CBA guidance in the UK

The foundation for CBA in the UK for the public sector is HM Treasury’s ‘Green Book’ ,5 which defines an approach to CBA grounded in welfare economics. Many other guidelines relevant to UK regulation claim to conform to the Green Book, but there is still considerable difference between those guidelines and an example from the financial sector is explored below.

In the financial sector, the FCA published its CBA guidance in July 2024.6 It states:

‘Doing CBA allows us to judge whether a policy is consistent with our proportionality principle. This says that any cost we impose on a person, or on the carrying on of an activity should be proportionate to the benefits we expect as a result. CBA also tells us whether a policy would disproportionately affect any firms or groups in society…The process of conducting CBA can produce valuable insights for the policy-making process, which help to refine the final policy decision.7

CBA are published as part of a consultation on a policy proposal, before the final policy is finalised. We note, though, that the guidance says that the FCA undertakes ‘CBA by identifying and estimating the costs and benefits of our preferred option’. 8

Given the FCA’s primary objectives of consumer protection, market integrity, and competition, the guidance places particular emphasis on impacts on consumers (e.g. harm, ease of access, protection from fraud, wellbeing) and impacts on markets (e.g. market stability, systemic risk, liquidity, innovation).

A feature of the FCA guidance is the use of standard cost models to estimate the costs of regulation. These are not novel (e.g. they were proposed by the EU in 2004,9 and in 2005 the UK published its own guidance to a standard cost model.10 Some stakeholders are concerned about the relevance of these costs,11 but there is also the possibility of bespoke compliance cost surveys used for more complex interventions.

More recently, the UK’s PSR has published a consultation on the use of CBA.12 The PSR’s view on CBA is conventional, and avoids a one-size-fits-all approach (it does not include the use of standard cost models). It applies ‘standard best practice principles of economic appraisal, such as those set out in the Green Book, 13 but does allow for some deviation. CBA will be used when legally required and also when desired, although the PSR may opt for ‘higher-level appraisal’14 instead. Furthermore, the intention of CBA are not to produce single point estimates, but to explain the costs and benefits to stakeholders by using CBA as a communication tool.

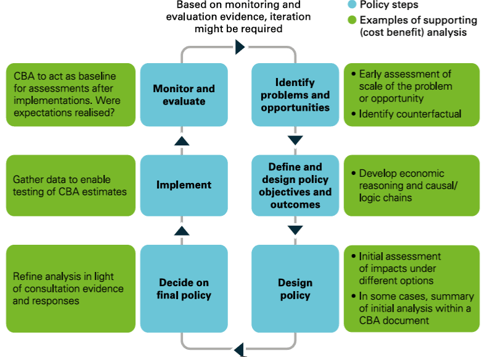

The PSR states that CBA should be integrated into policy development, not used to confirm a final policy. The role of CBA at each stage of the policy cycle is shown below:

The consultation on the proposal has just concluded, and the final proposals may differ, though points that could be addressed include the below.

- The assessment is purely economic and is not a full business case for policy change, using for example HM Treasury’s Five Case Model 15 that identifies four other dimensions, namely strategic, commercial, financial and management.

- Risk and uncertainty are recognised, as are ‘causal chains’, but behavioural issues are given only a token mention. See Box 1 for how causal diagrams can be used to expand the one-dimensional view of causal chains, and include the more subjective factors.

- Estimation bias is mentioned (e.g. optimism bias on the cost of compliance), but no remedies are proposed, e.g. benchmarks.

However, there is also a need to maintain proportionality of the assessment to the scale of the impact being assessed. Therefore, the above enhancements might only be appropriate in the more complex cases.

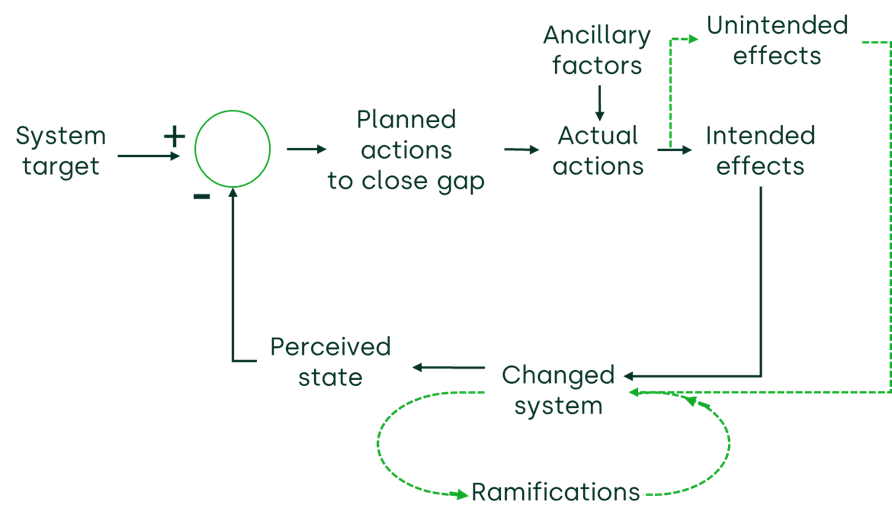

Box 1 Causal diagrams

Although CBA guidance refers to a ‘causal chain’, in practice there are causal loops, applying reinforcing or adverse effects. System-thinking models can help to clarify possible effects, though the diagrams of models can become very complex. A simplified version is shown in the model below; the basic cybernetic loop is shown in a solid line, where a difference between the target and perceived state triggers a corrective response to bring the system back on target. However, in practice there may be ancillary factors within the organisation and outside that influence the corrective planned action. Furthermore, the action implemented can have both the intended effects and some unintended side-effects. The intended actions change the system, but so do the side-effects, and as the system changes it can lead to ramifications that lead to further autonomous changes within the systems.

In the commercial world, the most common source of ramifications is competitors who respond, often to frustrate the initial intention. In the public policy sphere, institutional rivalries or disadvantaged stakeholders may act to frustrate change.

The energy transition to net zero offers a contemporary example where the desire to follow a target faces repeated challenges from ancillary factors of affordability, the unintended effect of the visual impact on the environment from new power lines, as well as the ramifications of the ‘carbon leakage’ of some affected industries moving abroad, with impact on employment.

EU practice

The European Parliament’s Committee on Legal Affairs commissioned a report on the current initiatives for better regulation.16 The main findings include the below:

- ‘a transition from the use of cost-benefit analysis towards multi-criteria analysis;

- a move from pure evidence-based towards evidence-informed and also foresight-based policies;

- the completion of the policy cycle with the introduction inter alia of ex post evaluations and fitness checks;

- the emergence of a strong (but still insufficiently funded regulatory oversight body;

- the growing role of the European Parliament in the better regulation domain; and

- the slow and partial development of the better regulation agenda in the Member States .’17

The most striking contrast with the UK is the moving away from CBA to MCA—however, this does not preclude the use of a benefit–cost ratio (BCR) as one of the criteria. The report emphasises that there is not a move away from quantification of impacts, but recognition of other factors such as sustainability and resilience. It should be noted that MCA is susceptible to distortion by those with a preferred solution in mind—the exercise should therefore be conducted with expert facilitation and a rational method used for determining weights and scores, such as Analytic Hierarchy Processing (AHP), discussed below. Ex post evaluation should also be used and include a quantitative estimate of impacts.

Is there divergence between the UK and EU?

One can view the EU’s move to MCA as either a rejection of CBA or an enhancement of it recognising that there are many other factors to be considered, not only the monetary. This is not in opposition to the UK’s Green Book, where there is an entire annex dedicated to non-monetisable factors, including environmental techniques and effects, land values, energy efficiency and greenhouse gases, life and health, and travel time. The environmental category proposes a natural capital approach18 and there is also the potential for considering qualitative factors. In short, the UK’s CBA approach encompasses many of the sustainability and resilience criteria that are included in the MCA preferred by the EU.

The Green Book also permits the use of MCA (referred to as ‘MCDA’ in the Green Book) for moving from a longlist of options to a shortlist, but requires a particular form of MCA, namely the ‘swing weights’ technique, based on SMARTS (Simple Multi Attribute Rating Technique with Swings) and SMARTER (SMART Exploiting Ranks), both developed by Edwards and Baron (1994).19 There are many more MCA approaches that have been developed—one popular method is AHP, which offers a pair-wide comparison approach to identifying the relative importance for both of the decision-making criteria and the performance of an option for each criterion. This appeals to decision-makers as it allows their expert judgements to be pooled—though there are several theoretical limitations to this popular method.20

Way forward

The need to assess the impact of public policies and regulation prior to implementation will ensure a future for impact assessments. They will be supported by the analysis of benefits versus costs, though the exercise will not always be termed CBA. It is beneficial for the exercise to be part of the policy formulation process, rather than simply being applied to confirm the suitability of an already-developed policy.

The exercise can also be used as part of the change-management process, to communicate the benefits to stakeholders. An ancillary benefit is also to safeguard the reputation of the regulators themselves, as they are able to show that their decisions stem thorough assessments and rigorous analysis . Whatever the label, the exercise will not be constrained to considering monetisable factors only, and there is increasing recognition of factors linked to sustainability and resilience. Finally, to continually improve the quality of the assessment process, there needs to be post-implementation reviews of the outcomes to provide feedback on the design of future assessments.

1 Booth, R. (2021), ‘Investment appraisal in the round: why MCA?’, Agenda, February.

2 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2012), ‘Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance’.

3 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020), ‘Regulatory Impact Assessment’, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a9638cb-en.

4 Ibid., p. 6.: ‘(i) Always start at the inception phase of the regulation-making process; (ii) Clearly identify the problem and desired goals of the proposal; (iii) Identify and evaluate all potential alternative solutions (including non-regulatory ones); (iv) Always attempt to assess all potential costs and benefits, both direct and indirect; (v) Be based on all available evidence and scientific expertise; (vi) Be developed transparently with stakeholders, and have the results clearly communicated.’

5 HM Treasury (2022), ‘The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation’.

6 Financial Conduct Authority (2024), ‘Statement of policy on cost benefit analyses’, July.

7 Ibid., p. 6.

8 Ibid., p. 7.

9 Payment Systems Regulator (2024), ‘Draft statement of policy on our cost benefit analysis framework’, September.

10 Ibid.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 HM Treasury (2022), ‘The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation’.

14 Payment Systems Regulator (2024), ‘Draft statement of policy on our cost benefit analysis framework’, September, p. 5.

15 HM Treasury (2018), ‘Guide to Developing the Project Business Case’.

16 Directorate-General for Internal Policies (2022), ‘Assessment of current initiatives of the European Commission on better regulation’, June.

17 Ibid., p. 6.

18 This includes air quality, noise, waste, recreation, physical health, amenity value, landscape, water quality, flood risk and erosion, vulnerability to climate change, biodiversity, nature-based carbon reduction and soil erosion .

19 Edwards, W. and Barron, F.H. (1994), ‘SMARTS and SMARTER: Improved simple methods for multiattribute utility measurement’, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 60:3, pp. 306–25.

20 Munier, N. and Hontoria, E. (2021), Uses and Limitations of the AHP Method, Springer International Publishing.

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More