Decoupling electricity and fossil fuel prices: bright idea or lights out?

The prolonged period of high energy prices in Europe has called into question the current design of electricity markets, and in particular the direct link between gas and electricity prices. Various short-term measures have been adopted to break this link, and some more fundamental changes to electricity markets are currently under discussion. What are their benefits and potential issues?

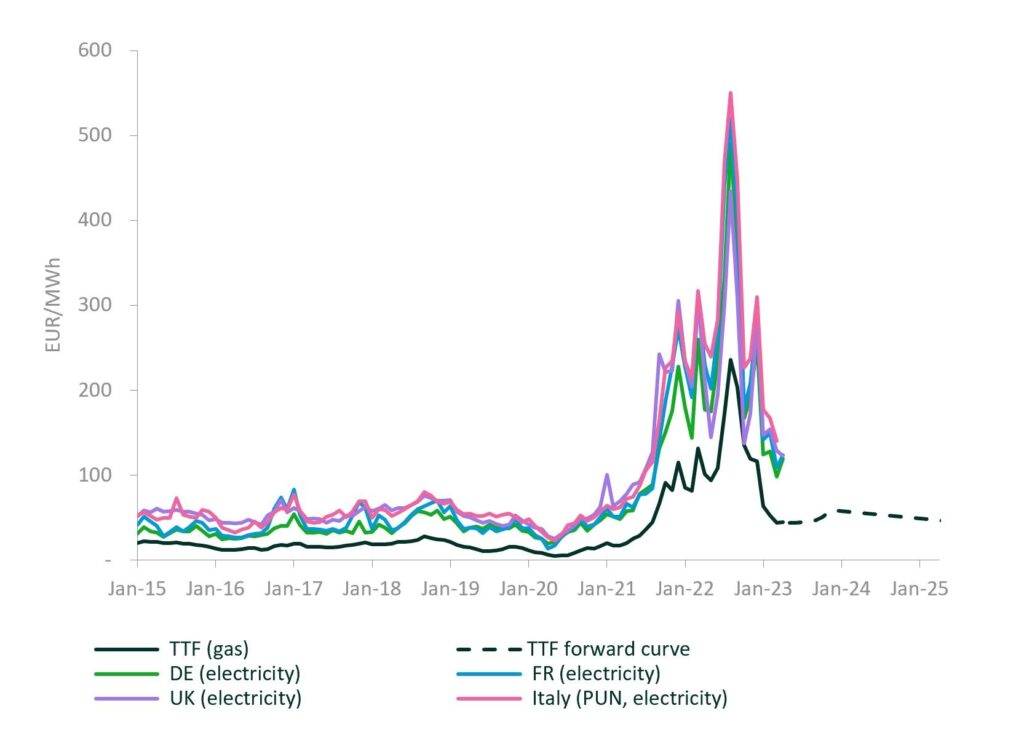

Over the last 18 months, the price of natural gas in Europe has increased substantially. To a large extent, this has reflected gradual reductions in the supply of natural gas from Russia across 2022, but the price increases actually started after COVID-19 restrictions were lifted. In more recent months, the upward pressure has eased, but prices remain higher than historical averages (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 European wholesale electricity and gas prices

Source: Oxera analysis of Bloomberg and Gestore dei Mercati Energetici data.

As Figure 1 shows, electricity prices have broadly followed changes in gas prices. This is due to the fact that, in Europe, the price of electricity is determined through hourly (and, in many countries, sub-hourly) auctions, where the clearing price (i.e. the price paid to all generators in the auction) is determined by the offered price of the most expensive generator that is needed to meet demand in a given hour.

Each hour, generators in European wholesale markets submit offers reflecting the prices at which they are willing to supply electricity, and off-takers (e.g. electricity retailers, large industrial users) submit bids reflecting the prices that they are willing to pay for the quantities of electricity that they require.

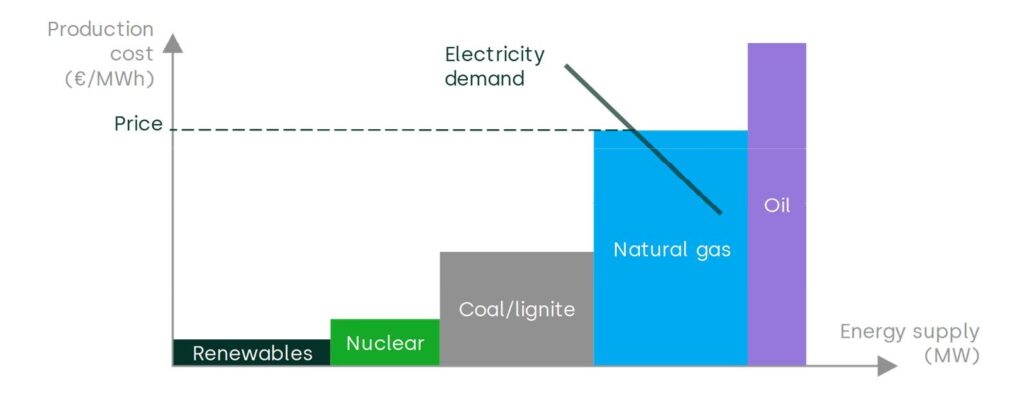

This bidding process is depicted in Figure 2 below, which shows a hypothetical demand schedule reflecting the bids made by off-takers (demand curve), and a hypothetical supply schedule reflecting the offers made by the different generators. The supply schedule increases in large part because of differing levels of variable (or ‘marginal’) costs of the various technologies (shown with different colours). While renewables have very low (or even zero) marginal costs, thermal plants incur fuel costs to generate electricity—and therefore generally have higher offers. However, all generators receive the clearing price, which is determined by the point at which the bid and offer schedules intersect.

Figure 2 Price setting in European electricity markets when natural gas prices are high

Source: Oxera.

While the marginal technology varies depending on the specific energy mix of a country, in Europe gas plants are often required to operate in order to allow the market to balance. The market price will therefore reflect the offers of gas-fired plants—thereby frequently making them the ‘marginal’ source of power. When their fuel costs increase, as has recently been the case, wholesale electricity prices will also increase. All the generators that appear to the left of natural gas plants in the merit order are ‘inframarginal’ generators, and stand to earn higher profits when market prices increase due to rising natural gas costs.

These higher profits have prompted concerns among many stakeholders and policymakers. In her 2022 State of the Union address, European Commission President, Ursula Von der Leyen, said:1

‘The current electricity market design – based on merit order – is not doing justice to consumers anymore. They should reap the benefits of low-cost renewables. So, we have to decouple the dominant influence of gas on the price of electricity.’

Similarly, when the UK government’s Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS—now the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero) launched its Review of the Electricity Market Arrangements (REMA) in July 2022, it stated that the review would:2

‘include exploring changes to the wholesale electricity market that would stop volatile gas prices setting the price of electricity produced by much cheaper renewables.’

Short-term solutions

A previous Agenda article highlighted how governments across Europe have been intervening in electricity markets, by providing support to market participants to alleviate the burden on consumers of energy price increases.3 Some of these measures have been costly, and many governments are now exploring ways to reduce their expenditure by decoupling the price of electricity from the price of gas.

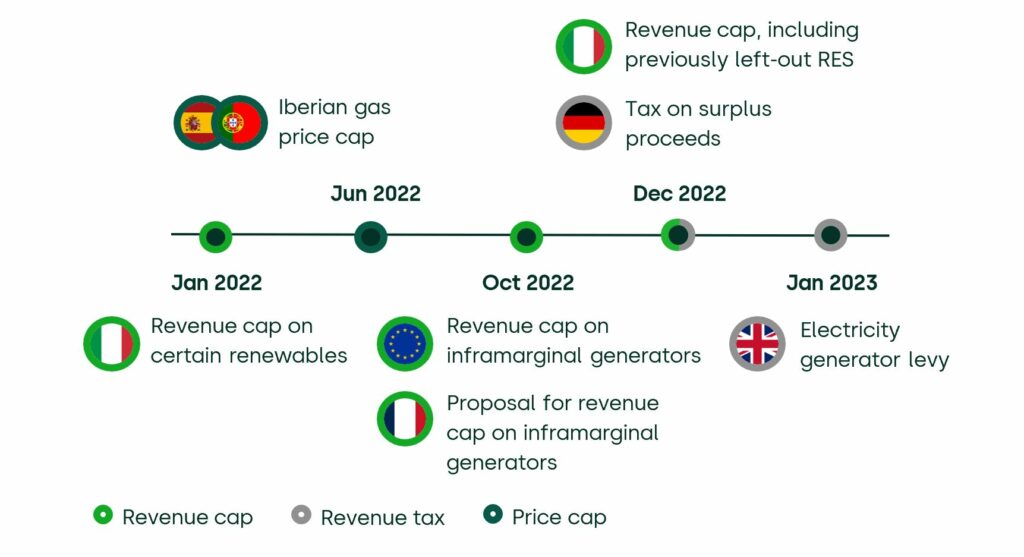

There are two main types of short-term measure,4 both of which can be considered de facto windfall taxes: capping the revenue that inframarginal generators can retain from the market; and taxing electricity revenues above a certain level. Approaches have varied across Europe. A third type of measure was adopted in Spain and Portugal, with the ‘dynamic’ price cap on gas generation. Figure 3 below illustrates when and where these different measures have been put in place.

Figure 3 Timeline of short-term policies across Europe

Source: Oxera.

Among the first attempts to reduce wholesale electricity prices was the ‘Iberian price cap’ introduced in Portugal and Spain in June 2022. This year-long ‘dynamic’ price cap on gas used for power generation set the maximum price at €40/MWh for the first six months, and is increased by €5/MWh per month until May 2023.5 As the price of gas during the energy crisis regularly exceeded €100/MWh, this effectively reduced the prices on Iberian wholesale markets relative to the price that would have prevailed absent the intervention, while only ‘compensating’ gas generators.

In most other countries, measures have more explicitly targeted inframarginal generation. In October 2022, a temporary revenue cap of €180/MWh on inframarginal electricity generators was introduced at the EU level. However, member states are allowed to implement lower revenue caps if they wish.6

As far back as January 2022, the Italian government introduced a revenue cap on certain renewables, with the cap ranging between €56/MWh and €75/MWh.7 A second measure was introduced in December 2022, capping revenues of certain renewable energy sources (RES) (excluded from the previous measure) and inframarginal generators at the EU cap of €180/MWh.8

The French Parliament has adopted a cap that ranges between €40/MWh and €175/MWh, plus an allowance for fuel and CO2 costs, depending on the technology, which applies from 1 July 2022 until 31 December 2023.9

Similar forms of taxation have been introduced in both Germany and the UK. In December 2022, Germany introduced a tax on technology-specific ‘excess profits’ from electricity generation based on renewables, lignite, nuclear and waste.10 This tax takes 90% of the revenue that a particular generator earns above the ‘reference’ price for its technology.

In the UK, the government has introduced an ‘Electricity Generator Levy’, imposing a 45% tax on ‘exceptional receipts’ generated from the sales of wholesale electricity at an average price in excess of £75/MWh over an accounting period. This levy will be in effect from 1 January 2023 until 31 March 2028.11

Long-term solutions

The current market design, which features the ‘pay-as-clear’ auction described above, was initially conceived for an electricity system that relied primarily on fossil fuels and large thermal plants.

Decarbonisation has changed this, with the current electricity grid characterised by a higher penetration of RES. Increasingly, the grid is therefore supplied by generators whose costs have not increased with the cost of natural gas, while their revenues (in some cases) have.

The increasing growth of RES also creates other problems for the grid, such as increasing the difficulty of balancing supply and demand, and depressing wholesale prices. In a decarbonised future, with RES frequently representing the marginal technology, wholesale prices are often likely to be reduced to their marginal costs (i.e. near zero), resulting in price cannibalisation, which limits the potential for RES plants to recover their capital costs.

These challenges have led to some stakeholders advocating for more fundamental changes to electricity markets. In what follows, we discuss three different long-term solutions, the first of which effectively extends some of the temporary measures described above, while the second and third reflect fundamental adjustments to market design.

Extending the current revenue cap for inframarginal generators

In a recent consultation, the European Commission discussed the possibility of extending the previously discussed revenue cap on inframarginal generators beyond its expected expiry date (30 June 2023).12 In this way, this mechanism would form an integral part of the electricity market design, rather than an ‘emergency’ measure, as initially planned. Some stakeholders, including ACER (the EU Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators) and CEER (the Council of European Energy Regulators), expressed their concerns about this measure, and put forward alternative proposals such as shock absorbers or circuit breakers, which would effectively limit inframarginal revenues only in extreme circumstances.13 The Commission has recently announced that it will continue to monitor the effects of the current measure and then form a view on its possible extension, although it seems to be cautious about making the cap a permanent feature of EU electricity markets.14

‘Decoupling’ gas and electricity prices through Contracts-for-Difference (CfDs) and Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs)

This approach involves moving many (new, but potentially also existing) inframarginal generators onto CfDs or PPAs, two types of long-term contract commonly used to support RES development.15

Under such an approach, a key question would arise over whether and, if so, how generators should be transferred to CfDs. If the generators were required to adopt CfDs, their current remuneration would be expected to be reduced and set at the level of other CfD-supported generators. If existing generators were to voluntarily adopt CfDs, this would imply that they perceived these to have some important long-term benefits, such as reducing their exposure to lower (and possibly negative) electricity prices in future as RES capacity expands. In any event, a balance would need to be struck between a ‘fair’ price that appropriately remunerates generators while ensuring lower prices in the long term for consumers, which could be particularly challenging in the context of highly uncertain future market outcomes.

While in a previous consultation the Commission explored the possibility of extending CfDs to existing generators, in its most recent proposed reform of the electricity market it has highlighted that CfDs should be limited to new investments and not applied retroactively.16 Therefore, it seems unlikely that mandatory CfDs will be introduced for existing European generators.

A split wholesale market

A number of academics have put forward proposals for how the wholesale market could be split to cater for the particular characteristics of different plant types, while also benefitting consumers. These proposals typically promote the creation of a wholesale market for either renewable or intermittent plants, and another wholesale market for dispatchable plants (typically limited to non-renewable or nuclear generators).17

Some European countries have explored the possibility of implementing the split market design. In the UK, the REMA consultation included a proposal to create two separate markets for:

- variable power—or the ‘as available’ market, whose costs would reflect the long-run marginal cost of renewables;

- firm power—or the ‘on demand’ market, which would include thermal units, with prices set in line with the short-run marginal costs, which are typically fuel costs (in line with the current system marginal price mechanism).

Splitting wholesale prices also generally involves ambitious changes on the demand side. Under the ‘split’ market, consumers will not only benefit from the lower costs of renewables, but will also bear the ‘risk’ of their variability (as they will choose their own mix of ‘as available’ and ‘on demand’ power). While a broader extension of CfDs could be achieved in the short/medium term, the changes on the consumer side seem to be more challenging.

At the EU level, there appears to be less support for a split market design, as this idea was not discussed at all in the Commission’s most recent proposal.18 Furthermore, the Greek government’s proposal from July 2022 on creating a two-stage day-ahead market, with renewables competing in the first stage and fossil generators in the second, does not appear to have progressed beyond the initial stage.19

Benefits and potential issues

All of the solutions discussed above could reduce consumer electricity prices in the short to medium term, because they all remove the link between gas and electricity prices for inframarginal generators.

It is also worth noting that some of the longer-term measures could provide a number of benefits to the energy market that go beyond reducing prices for consumers, although a full evaluation of these benefits is outside of the scope of this article. For example, splitting the electricity market between variable and firm power could allow for consumers to choose the quantities of firm power that they want to purchase. This would allow for the market to determine a price for reliability, in contrast to current market arrangements which rely on the government or the grid operator to determine how reliable the electricity system should be.

However, these policies could introduce at least three types of unintended consequence:

- reduced confidence in regulatory stability;

- shifting investment projects to more ‘favourable’ jurisdictions;

- increased incentives for avoidance of RES-specific taxes, levies and other schemes aimed at controlling profitability.

For example, confidence in regulatory regimes could be undermined if the policies are perceived by investors as unexpectedly undermining their ability to earn a reasonable commercial return. This could lead to an increase in regulatory risk, especially when market rules are changed with limited notice or consultation.

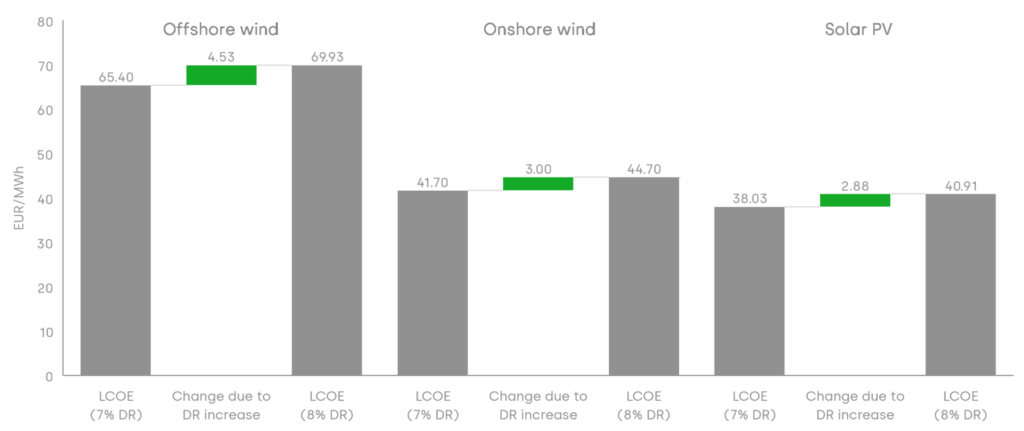

Renewable generation projects are capital-intensive, with c. 60–70% of (onshore and offshore) wind costs reflecting capital expenditure (CAPEX),20 and require a long time to build (offshore wind can take three to seven years, for example).21 Therefore, increases in the costs of capital can have substantial effects on the cost of renewables, and therefore also the prices that consumers have to pay.

To demonstrate the impact that this could have on consumer energy bills, we provide an indicative estimate of the impact that a one-percentage-point increase in the cost of capital would have on consumer electricity bills in 2030. Figure 4 below shows that a one-percentage-point increase in the cost of capital for an offshore wind generator would result in a 6.9% or €4.53/MWh increase in its levelised cost of electricity (LCOE).22 For an onshore wind generator, we found that the increase would be €3/MWh, or 7.2%. For solar PV, the same increase in the cost of capital would lead to an increase in the LCOE by €2.88/MWh, or 7.6%. If these increases in LCOE fed into consumer electricity bills, EU consumers would spend approximately €8.1bn per year more than they would in the absence of the increase.23

Figure 4 LCOE increase as a result of a one-percentage-point increase in the WACC for different renewable energy sources

Source: Oxera analysis. Assumptions to the LCOE calculations are based on the documents in the zip file available at http://jeodpp.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ftp/jrc-opendata/POTEnCIA/Central_2018/Central_2018_EU28.zip.

The increase in regulatory risk could also lead to the deferral or reduction of investments in renewable generation. This would happen if governments were unwilling to pay the higher prices that renewable generators require in order to be compensated for their additional regulatory risk. It could also happen if renewables investors decided to wait until there was more forward-looking regulatory certainty about how they would be compensated. Such an outcome would be damaging for decarbonisation, especially as countries such as the UK are decarbonising slower than is needed to achieve net zero.24

Projects may relocate to more ‘favourable’ jurisdictions

To the extent that developers consider that they can capture value from the merchant nose25 of a project, they may choose to locate in countries where inframarginal generator profits are not subject to a cap, or are at least capped at higher levels.

Incentives for tax avoidance

As is also the case in other areas of the economy when taxes rise, there may be an increase in incentives to avoid the short-term measures.26 For example, if companies are vertically integrated, the upstream entity could sell electricity to the downstream entity at a discount, meaning that it would not have to pay the tax. This would leave the company in a better position than if it sold its electricity at full price on the open market, as the price that the retailer charges is determined by the wholesale price, both when companies sell directly to their subsidiaries and when they do not (i.e. it should be roughly equal in both scenarios). However, in a scenario where the company sells its electricity at full price on the open market, it has to pay an additional tax. Such trading may be a violation of the ‘arm’s length’ transfer pricing principle,27 and many companies may therefore not want to engage in it. However, the existence of the tax will increase incentives for such avoidance strategies.

Current and future consumers: a difficult balance

The energy crisis has led to governments across Europe adopting a range of responses, some of which have been short-term measures that attempt to decouple the price of electricity from the price of natural gas. In general, these measures have reduced the remuneration of inframarginal generators relative to a situation where the measures were not introduced.

The longer-term measures that policymakers appear to be taking most seriously do not reduce the remuneration that existing generators would receive. This is because the European Commission seems to be looking unfavourably on keeping the inframarginal revenue cap as an enduring feature of European electricity markets, and does not appear to support moving existing generation onto a two-way CfD.

The shorter-term measures, introduced in response to the energy crisis, have largely affected existing rather than future electricity generation. On the one hand this could mean that, in some cases, European governments have managed to reduce customer bills (compared with a situation without these measures) without reducing the incentives for construction of future generation. On the other hand, the existence of these short-term measures could reduce the trust that market participants have in the stability of European policy and regulation. If this were the case, the biggest impact of short-term measures might be increased costs for future consumers as a result of a higher cost of capital for RES projects. The additional regulatory risk could also slow the pace of energy transition, and lead to companies being more selective in where they build future generation, which would further disadvantage future consumers.

1 European Commission (2022), ‘2022 State of the Union Address by President von der Leyen’, speech, 14 September.

2 Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (2022), ‘UK launches biggest electricity market reform in a generation’, press release, 18 July.

3 Oxera (2022), ‘Stepping on the gas: European emergency measures to deal with high energy prices’, Agenda, November.

4 That is, measures that are not intended to have lasting effects on energy market design.

5 European Commission (2022), ‘State aid: Commission approves Spanish and Portuguese measure to lower electricity prices amid energy crisis’, press release, 8 June.

6 Council of the European Union (2022), ‘Council Regulation 2022/1854’, Official Journal of the European Union, 7 October.

7 The exact threshold of the cap depends on the bidding zone in which the plants fell. See Decreto Legge 4/2022, article 15-bis, 27 January.

8 Legge 197/2022, Article 1, comma 30–38, 29 December.

9 Loi n° 2022-1726 du 30 décembre 2022 de finances pour 2023, Article 54.

10 Bundesministerium der Justiz, ‘Gesetz zur Einführung einer Strompreisbremse’, part 3.

11 HM Treasury (2022), ‘Electricity generator levy. Technical note’, November.

12 European Commission (2023), ‘Electricity Market Design: Commission launches consultation on reform to support a clean and affordable energy transition’, press release, 23 January.

13 European Union Agency for Cooperation of Energy Regulators and Council of European Energy Regulators (2023), ‘ACER-CEER Reaction to the European Commission’s public consultation on electricity market design’, 14 February.

14 European Commission (2023), ‘Reform of Electricity Market Design’, SWD(2023) 58 final, 14 March, section 3.

15 A two-way CfD is an instrument that is often used to support RES generators and represents a long-term contract that allows generators to earn (approximately) a fixed price (expressed in €/MWh) over a period of time. It works by allowing generators to earn revenues from the wholesale market. If the fixed price is above the wholesale price, a further top-up is paid to generators. If it is below the wholesale price, generators pay back some of their wholesale market revenues. A PPA is a bilateral long-term contract between a generator and an off-taker (usually an industrial client).

16 European Commission (2023), ‘Reform of Electricity Market Design’, SWD(2023) 58 final, 14 March, section 2.2.

17 While these are two different approaches to splitting the market (i.e. renewable vs non-renewable and dispatchable vs non-dispatchable), the generators participating in the two pools would generally be very similar. The only generators that might participate in different pools depending on the definitions are nuclear and biomass.

18 European Commission (2023), ‘Reform of Electricity Market Design’, SWD(2023) 58 final.

19 The Greek proposal would achieve a split between dispatchable and non-dispatchable technologies (including nuclear) by creating the following two stages in the day-ahead market:

- in the first stage, non-dispatchable sources submit volume-based offers, but not price-based bids. These generators are remunerated through (bilateral or public) CfDs and have priority dispatch;

- in the second stage, the remaining load (net of what is already covered through offers from non-dispatchable units) is covered by dispatchable sources, for which the pay-as-clear mechanism applies.

See Council of the European Union (2022), ‘Information note 11398/22 ENER 366’, 22 July.

20 National Renewable Energy Laboratory (2021), ‘2021 Cost of Wind Energy Review’, December, pp. 6–8, 30.

21 We have assumed a four-year development period when calculating this range. Iberdrola, ‘How long does it take to build an offshore wind farm?’.

22 LCOE is defined as the net present value (NPV) of costs divided by the NPV of generation. It is the main measure used to estimate the costs of renewable generation. The LCOE calculations for wind and solar generators are based on the documents in the zip file available at http://jeodpp.jrc.ec.europa.eu/ftp/jrc-opendata/POTEnCIA/Central_2018/Central_2018_EU28.zip.

23 We calculated this by multiplying the LCOE for a generator constructed in 2030 by the amount of electricity that the given generator type would produce in 2030. The assumptions on the quantity of electricity generated are taken from the average of the Global Ambition and Distributed Energy scenarios used in ENTSO-E and ENTSOG (2022), ‘TYNDP 2022 Scenario Report’, April.

24 See, for example, Climate Change Committee, ‘Advice on reducing the UK’s emissions’.

25 The ‘merchant nose’ of a renewable project is the period after the project is constructed, but before it joins its support scheme, during which it receives wholesale market revenues. As receiving wholesale market revenues is often referred to as ‘merchant exposure’, the term ‘merchant nose’ refers to merchant exposure at the start of a project’s life.

26 Chiarini, B., Marzano, E. and Schneider, F. (2013), ‘Tax rates and tax evasion: an empirical analysis of the long-run aspects in Italy’, European Journal of Law and Economics, 35:2, pp. 273–293.

27 This is a principle of transfer pricing that states that the price for a transaction agreed between two related parties must be the same as the price agreed for a comparable transaction between two unrelated parties. See Arintass, ‘Arm’s Length Principle in Transfer Pricing’.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More