Digital securities and English law: the gold standard?

The UK Jurisdiction Taskforce (‘UKJT’), part of LawtechUK, has produced a Legal Statement on how English law supports the use of distributed ledger technology in equity and bond markets (also known as ‘digital securities’).1 To inform and support UKJT’s work, LawtechUK commissioned Oxera to provide economic analysis of the value of English law being supportive of digital securities.

As part of this research, we built on our previous work on the broader value of English law2 and the impact of blockchain in capital markets,3 speaking to various industry practitioners and analysing the economics of this new technology.4

Legal systems—a critical piece of capital markets infrastructure

Transactions typically create economic value. In other words, I focus on what I am good at and then trade with you for the things that you are good at, and—in this way—we are both better off than we would be otherwise. The benefits associated with specialisation and trading are sometimes called ‘gains from trade’. The legal systems that govern those transactions are important facilitators thanks to the predictability and confidence they create. A well-defined legal system can lower transaction costs and increase the volume and complexity of the transactions that can take place. In this way, the law can be seen as a platform on which other economic activity rests, and a critical piece of business infrastructure.5

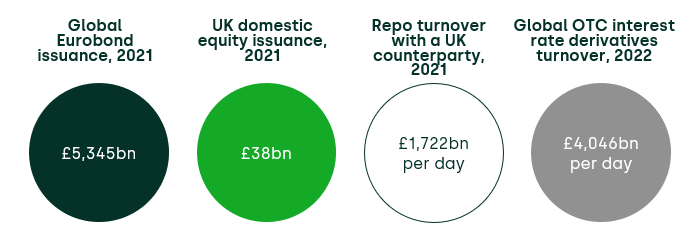

Oxera’s work was particularly focused on English law, which has been a global standard for contracts in many internationally mobile markets (e.g. shipping, commodity trading and insurance).6 Capital markets are another excellent example of this. As shown in Figure 1 below, the value of transactions under contracts governed by English law is significant.

Figure 1 Financial markets governed by English law

Source: Oxera, based on data from Bank of International Settlements, London Stock Exchange and International Capital Market Association.

English law has historically been seen as an attractive legal system in various capital markets,7 in part due to its flexibility, predictability, and constant evolution to deal with innovation and new technology. These characteristics make English law well placed to facilitate trading in digital securities, which represents a material innovation in the technology underpinning capital markets.

What are digital securities?

The term ‘digital securities’ is often used with different definitions in various settings. In this context, we are referring to the use of distributed ledger technology (‘DLT’) as a means of issuing and representing traditional securities, such as shares and bonds, in a digital form.8 A short technical summary of DLT and blockchain is provided in Box 1.1.

Box 1.1 Blockchain and distributed ledger technology

The terms ‘blockchain technology’ and ‘distributed ledger technology’ are often used interchangeably. Strictly speaking, however, ‘blockchain’ describes a technology, while ‘distributed ledger’ describes a functionality (which blockchain technology can enable).

A distributed ledger refers to the ability to record information (such as the history of transactions involving an asset) in multiple places at the same time. Unlike a centralised database, updates to a distributed ledger can be proposed by any node in the network. Since any node can propose updates to the database, a protocol is needed to ensure consensus among participants, and to determine the correct copy of the ledger. Once consensus has been reached, all participants in the network update their copies of the ledger to the latest version.

Blockchain technology allows the different (and ‘distributed’) parties to achieve consensus on the data set, effectively achieving a distributed ledger. In this case, the distributed ledger is formed of a growing sequence of records (called ‘blocks’) that are securely linked together using cryptographic ‘hash’ codes.

Source: Oxera.

In capital markets, many different issuers and investors transact with each other, producing huge amounts of information as ownership of assets changes hands. Much of the infrastructure of capital markets is devoted to ensuring the efficient flow of that information.

Technology has helped to improve the efficiency of these flows. For example, paper certificates of ownership have, over time, been replaced by entries in databases operated by specialised financial institutions, such as custodians and central securities depositories (CSDs).

Collectively, Blockchain and DLT have the potential to greatly improve the efficiency of capital markets infrastructure. There are many different ways this can be done in practice. Without going into all of these, we can categorise digital securities into two broad ‘models’:

- native digital securities—when a security is issued directly in a DLT-based system and does not have any other representation outside the DLT network;

- digital representations of existing securities—when securities are initially issued within a traditional system, while the recording and post-trade handling of the securities is subsequently enabled in a DLT environment. Here, securities in the conventional system are referenced or represented by tokens.

Why might digital securities be adopted?

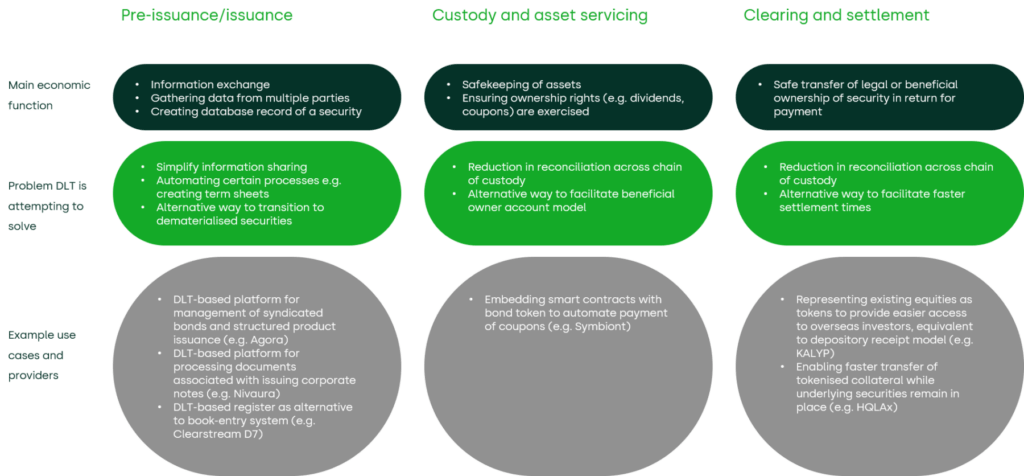

The impact of DLT on capital market efficiency is still subject to uncertainty and debate.9 Feedback from our interviews with market participants highlighted that there may be several potential benefits of digital securities. DLT-based systems have already been shown to be technically feasible, and in certain use cases they are commercially viable, particularly where they provide a solution to inefficiencies associated with conventional systems. These use cases include simplifying information sharing, reducing reconciliation costs, and automating certain processes (e.g. coupon payments or collateral repo transactions).

Figure 2 summarises existing areas of capital markets activity where DLT networks are already in use.10

Figure 2 Existing use-cases/services using DLT

In 2023, both the UK Financial Conduct Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority will launch pilot schemes that allow financial market infrastructure providers and users to test and adopt DLT-based trading and settlement systems. Outside the UK, various proof-of-concept experiments and pilot schemes have been undertaken over the last decade—along with updates to regulation and legislation to support digital securities.11

Although digital securities currently account for a small proportion of the total activity in equity and bond markets, successful commercial applications could scale up very quickly. This is because much of the infrastructure in capital markets is characterised by ‘network effects’; this means that the more users join a platform, the greater the value of the platform to the users, so the easier it is to attract more users. Markets that are characterised by network effects are prone to ‘tipping’.12

Nonetheless, there are barriers to adoption that would need to be addressed before this scaling can happen. These include security and privacy concerns around DLT networks, a lack of interoperable technological standards, the need for clear business, commercial rationale for coordinated investment, and a requirement for a suitable regulatory framework to be in place.

To some extent, many of these barriers to adoption have been (or are being) addressed. However, another key barrier is a perceived lack of private law clarity, which we turn to next.

The value of English law to digital securities markets

So how might greater clarity about digital securities within English law create economic value, both for the UK and for the English legal system more widely?

Given the use of English law outside the UK, it is useful to think about the economic value that could be created in internationally mobile transactions.13 Here, there may be both narrow and broad benefits to English law being used for internationally mobile transactions:

- narrow benefits: additional activity in the legal and professional services ecosystem that is based in the UK (and therefore familiar with English Law);

- broad benefits: internationally mobile transactions governed under English law which promote English law as the global standard.

Both types of benefits work through two overarching and mutually reinforcing mechanisms.

First, the use of English law internationally makes English law itself more valuable through the continuous building of precedent and legal expertise. Legal systems have network effects similar to those that we mentioned earlier in the context of financial transactions; specifically, the more a legal system is used, the more attractive it will be for others to use.

This means that as English law becomes a global standard for digital transactions, it provides certainty and predictability in the law, and allows the law to evolve continuously to better reflect the issues that businesses face.

Second, the widespread use of English law makes the UK a more attractive trading and financial centre in the international economy, supporting the economy directly through the location of high-value activity, and providing UK firms access to a world-leading professional and financial services cluster.

These clusters of financial, legal and professional services contribute significantly to the wider UK economy. It has been estimated that financial and related professional services contributed £238bn to the UK economy in 2020.14 In 2021, the legal services sector contributed £30.7bn to the UK.15 The UK has been a growing global Fintech hub, with the sector employing over 75,000 people,16 and it is estimated to be worth £6.6bn to the UK economy in the first half of 2022.17

Where to next?

The debate around the potential impact of digital securities is a useful reminder of the role that legal systems play as critical pieces of economic infrastructure.

The role of English law as a platform on which future digital securities markets rely depends on whether market participants have confidence that it supports transactions enabled via DLT. This is something which the UKJT Legal Statement aims to provide.

The nature of network effects in capital markets means that once a platform has gained critical mass, it can quickly pull away from its rivals in popularity. The key question for policymakers and market participants will be how to ensure that English Law is well placed to be the legal system of choice when digital securities achieve this critical mass.

1 Lawtech is a government-backed initiative established to support the transformation of the UK legal sector through technology. See Lawtech UK (2023), ‘UKJT Legal Statement on Digital Securities’, 9 February.

2 Oxera (2021), ‘Economic value of English law’, October.

3 Oxera (2016), ‘The debate about blockchain: unclear and unsettled?’, Agenda, August.

4 For further insight, see the Oxera research in Lawtech UK (2023), ‘UKJT Legal Statement on Digital Securities’, 9 February.

5 See Oxera (2021), ‘Economic value of English law’, October.

6 Markets in which the parties can choose the law that governs the contract. The legal framework is therefore not necessarily linked to the physical location of the parties, assets or processing technology.

7 There is broad academic literature on the relationship between legal systems and capital markets. See, for example, La Porta, R., Lopez-De-Silanes, F., Shliefer, A. and Vishny, R.W. (1997), ‘Legal determinants of external finance’, Journal of Finance, 52:3, pp. 1131–1150.

8 The term ‘digital securities’ is sometimes used interchangeably with ‘tokenisation’. However, tokenisation is also used specifically to refer to models in which a pre-existing security is represented in a separate DLT-based system.

9 To really understand the potential cost reductions, the costs along the entire value chain (i.e. those of fund managers, brokers, clearing agents, custodians, CCP and CSD) would need to be estimated and then compared with the costs of a transaction processed by a DLT-based system. There are few available estimates of the costs of the entire current value chain, and estimates of the costs of a DLT-based system (operating at a similar scale) have not yet been published. The cost savings are likely to vary by the type of security, as well as by the financial centre.

10 For other discussions of potential use cases see, for example, Cunliffe, J. (2022), ‘Innovation in post trade services – opportunities, risks and the role for the public sector’, speech by Sir Jon Cunliffe at the AFME Conference, 28 September; OECD (2020), ‘The tokenisation of assets and potential implications for financial markets’, OECD Blockchain Policy Series.

11 For instance, France introduced a 2017 law governing securities issued on distributed ledgers, and Germany introduced a law permitting the issuance of unregistered securities via DLT in 2021. An EU DLT Pilot regime is due to come into force in March 2023, see European Securities and Markets Authority (2022), ‘ESMA publishes report on the DLT Pilot regime’, 27 September.

12 ‘Tipping’ refers to the ‘tendency of one system to pull away from its rivals in popularity once it has gained an initial edge’ generally driven by strong network effects. See Katz, M.L. and Shapiro, C. (1994). ‘Systems competition and network effects’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8:2, pp. 93–115.

13 If English Law did not provide users of digital securities with the required level of certainty, there are a range of other legal systems that may end up being preferred. In such a scenario, domestic transactions would continue to use domestic legal systems, but internationally mobile transactions may switch from one legal system to another. We therefore focus our discussion of the benefits of legal clarity on internationally mobile transactions.

14 TheCityUK (2022), ‘Enabling growth across the UK 2022’.

15 TheCityUK (2022), ‘Legal excellence, internationally renowned’.

16 The UK FinTech market employed 76,500 people as of the first half of 2020; see TheCityUK (2021), ‘Key facts about the UK as an international financial centre 2021’.

17 The Global City (2022), ‘The UK: innovation hub for fintech’. According to analysis undertaken as part of The Kalifa Review, the UK had ten high-growth fintech clusters, see HM Treasury (2021), ‘The Kalifa Review of FinTech: Independent report on the UK Fintech sector by Ron Kalifa OBE’, 26 February.

Related

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More