Electric vehicles: a future without fuel duty?

The extension of the 5p cut to fuel duty in last week’s Budget from the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer makes this the 14th year in a row that fuel duty has been frozen or cut. While this might bring short-term relief to drivers in the ongoing cost of living crisis, the government is currently facing a future with a significant shortfall in revenues from fuel duty as the share of electric vehicles on our roads increases. Without action from government, this will lead to unwelcome trade-offs: additional government borrowing, cutting back on public investment or raising other taxes.

There is therefore a clear need to move away from the current system that is heavily reliant on fuel duty towards a more sustainable system that is sensitive to the changing nature of the roads sector. Given national net zero goals, such a system should still encourage the transition to electric vehicles (EVs) to curb emissions, but could also target some of the other negative impacts associated with road transport—such as congestion, noise, local pollution and accidents—all of which are predicted to increase along with road usage.

The design of any new tax system will therefore need to balance a range of policy objectives—but it will be particularly important to consider the distributional impacts of any new policy, both in terms of public acceptability and ensuring a ‘just transition’, as discussed below.

The road ahead

The way we drive and pay for the use of our roads is changing. Net zero goals and decarbonisation initiatives are encouraging the sale of electric vehicles (EVs), and governments around the world have been introducing schemes such as clean air zones and congestion charging to address a range of issues—from local pollution to congestion—that arise from road transport.

The challenge from an economic perspective is that, while road transport supports economic growth and development, it causes negative externalities. These are negative impacts for society as a whole (such as emissions, congestion, noise, local pollution, accidents, and wear and tear of the road surface), the costs of which are currently either not priced into the costs paid by motorists, or priced inaccurately. This means that motorists are not directly faced with prices that reflect the true environmental and wider societal costs linked to road transport, and as a result may choose to drive more than they otherwise would. This is particularly challenging given the pressure on the transport sector in the UK and elsewhere to reach net zero by 2050, coupled with the fact that that road usage is predicted to increase in the future, even with the transition to EVs.1

This is where tax policy comes in. Governments have a range of tools at their disposal to achieve their policy objectives—taxes being one of them. Taxes and charges can have a substantial impact on users and shape transport outcomes. Tax policy and its future design are particularly relevant to the road transport sector, as the shift to EVs will lead to an increasingly significant shortfall in tax receipts from fuel duty, which in the past provided an important source of revenue (£25.1bn in the UK in 2022/23).2

There is therefore a clear need to change the current system, which is heavily reliant on fuel duty, with a more sustainable system for pricing road usage and its associated negative externalities. For example, a more sustainable system could regulate traffic by targeting behaviour through pricing, while also ensuring stable tax revenues—which are vital to funding public services among other social priorities. In addition, tax levers could be used to encourage modal shift towards public transport, walking or cycling.

While a number of options are available, these need to be carefully designed and compared according to the policy objective(s) that they are trying to achieve and any resulting negative consequences. There will be trade-offs between purely fiscal objectives (implementing taxes to raise revenue) and wider economic and societal ones (supporting the net zero objective, tackling congestion, reducing accidents, etc). In this article, we set out the economics of taxation and how the various tax levers can be used to deliver different policy objectives. We then briefly discuss some of the options for replacing fuel duty, in particular drawing out the challenges arising with regard to potential distributional impacts and ensuring a just transition.

A just transition seeks to ensure that the substantial benefits of a green economy transition are shared widely, while also supporting those who stand to lose economically

Source: European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, ‘What is a just transition?’.

While this article focuses on the UK, many of the issues are felt acutely by other countries in the EU and elsewhere. Governments there face similar challenges when it comes to designing sustainable tax policy.

Taxes currently levied on the road transport sector in the UK

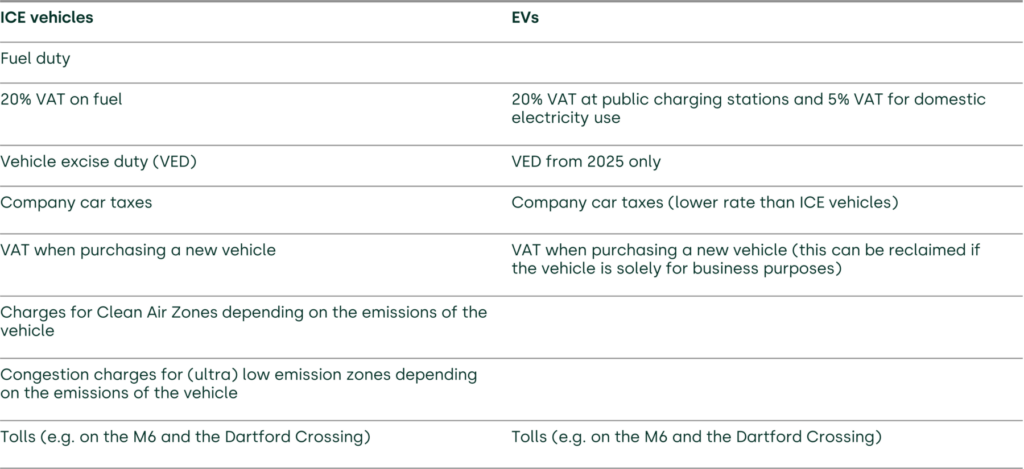

Currently, private users of the road network in the UK face a number of taxes and charges. However, these differ depending on whether the vehicle has an internal combustion engine (ICE) or is an EV. The table below provides a comparison of the taxes and charges faced by each.

Table 1 Overview of current motoring taxes and charges

Source: UK Government (2024), ‘Vehicle tax rate tables’, last accessed 13 March 2024.

The table highlights that ICE vehicles face more charges than EVs, and in some instances higher charges than EVs as a consequence of the emissions that they produce, as the current tax system encourages the use of more efficient vehicles with lower (or zero) emissions. However, currently only limited taxes (such as the London Congestion Charging Scheme) are designed to directly target some of the negative externalities from motoring that are not linked to emissions, such as noise, pollution, accidents and congestion.

In terms of raising revenue, the income from fuel duty provides the lion’s share of revenue received from motorists, at £25.1bn in 2022/23.3 This is more than three times larger than VED, which raised £7.4bn over the same period.4 EVs do not currently incur VED; however, from April 2025 both new and existing EVs will incur the lower first-year rate of VED, and the standard rate thereafter. The government has stated that this policy objective is to ensure that ‘all drivers begin to pay a fairer tax contribution’.5

Current challenges facing the road transport sector

Trends in vehicle manufacturing and consumer demand suggest that the number of EVs will rise significantly in the future.6 This will lead to fewer ICE vehicles on our roads that pay fuel duty.

The OBR forecasts that this increased take-up of EVs is expected to cost £13bn a year in lost fuel duty by 2030.7

Fuel duty is already regressive, as those households with cars on lower incomes spend a higher percentage of their household budget on petrol and diesel.8 This will only be exacerbated as higher-income households are more likely to switch to EVs (which are generally more expensive than ICE vehicles), leaving lower-income households to shoulder the burden of motoring taxes in their current form. However, any tax change that widens the tax base to include EVs will cause tension with the wider aim of supporting the transition to EVs. This is because government incentives (such as ongoing tax exemptions and past vehicle purchasing grants) have been influential in encouraging drivers to purchase an EV over an ICE vehicle.

Aside from the debate surrounding emissions and taxation, the DfT has forecast that road traffic in England and Wales will increase by 22% between 2025 and 2060,9 driven by both population growth and lower vehicle running costs (EVs have cheaper running costs than ICE vehicles). This means that the harmful impacts of road transport will also increase.

As a result, there is a need to design a future tax system that is sensitive to the changing nature of the roads sector and provides fairer and more accurate pricing of the external costs of road transport to society. However, it will be important that such a system still encourages people to make sustainable transport decisions and does not disproportionally affect households that are on lower incomes.

Designing taxes to achieve policy objectives

Different types of tax will contribute to different policy objectives. These policy objectives may compete with each other, giving rise to trade-offs between objectives, and no given tax is likely to meet all the potential policy objectives. In addition, the cost of implementation and efficiency of a tax policy in terms of achieving its objectives need to be considered carefully.

The challenges presented by the drive to decarbonise, and the resulting changing nature of our road transport sector, are likely to require a well-rounded series of policies that address the various government objectives.

Fiscal vs wider economic and societal objectives

In general, taxes can serve purely fiscal or wider economic and societal objectives.

Fiscal objectives

A major purpose of tax on road users is to raise revenue for the government, which can be used to fund the national road network as well as for other purposes.10 There are some exceptions to this on a local level (for example, revenues from London’s Ultra Low Emissions Zone (ULEZ) go straight into the London transport network)11. Even though the revenue from fuel duty is not hypothecated, sufficient funding of the road network is essential in order to alleviate some of the negative externalities (e.g. better road surfaces lead to less wear and tear).

The revenue-raising potential of any tax depends on the tax base and the rate of tax. In the case of fuel duty, as described in section 3, the shrinking pool of ICE vehicles on our roads will lead to a dramatic decline in fuel duty receipts. Without action from government this will lead to unwelcome trade-offs in terms of cutting back on public investment or raising other taxes considerably.

Wider economic and societal objectives

Taxes can also be used to reduce or manage demand for road transport by targeting the negative externalities that it causes. Fuel duty increases the price of fuel, which influences the amount of fuel purchased and encourages the use of more efficient vehicles, thus reducing emissions. VED rates are linked to a vehicle’s CO2 emissions, and thus also encourage the purchase of zero-emission vehicles.12

While supporting net zero ambitions is an important policy objective for governments, there are competing objectives surrounding tackling congestion, pollution and noise that are caused by road transport. Taxes can be used here to deter users from driving at certain times of the day or in certain locations, in order to alleviate traffic. This has been implemented in various Clean Air Zones (CAZ) across major cities in the UK as part of the government’s broader Air Quality Plan. Vehicles must pay a fee to enter a CAZ, depending on the emissions of their vehicle.13 As these schemes are linked to a specific geographic area, they can be determined by the local authority that implements them.

Equality

Any tax policy has the potential for unintended consequences, and this is particularly often the case when it comes to unintended effects on equality. Lower-income households already spend a greater proportion of their budgets on transport, are less likely to afford a zero-emission vehicle, and can be more heavily reliant on their car. A tax system that heavily penalises those who drive to work must take into account the fact that workers in more rural areas may not have the option to switch to public transport. This means that any new tax that is designed to offset the fall in fuel duty needs to be based on a thorough distributional analysis to ensure that appropriate mitigations can be included to support those on lower incomes.

A future without fuel duty?

It is clear that, as the tax base of remaining ICE vehicles on the roads continues to shrink, a new tax system needs to be designed to include drivers of zero-emission vehicles in some way. However, there is no clear equivalent to fuel duty for EV drivers—the electricity used for charging EVs could be taxed at public charging stations (and VAT is already included here), but it will not be possible for those EVs that are charged at home. This is because it is not clear how to differentiate between the electricity used to charge an EV and the electricity used for other household purposes.

Road pricing has often been presented as a possible solution, and a significant amount of work has been done on the design of such a system. There are lots of alternative options for road pricing, ranging from simple tolls to more complex and dynamic road pricing (e.g. using GPS or in-vehicle technologies). A simple system would have the benefit that it could be more easily rolled out and administered, while a more complex system would have the potential to address some of the other negative externalities from road transport. For example, the charge could be a function of distance travelled, with higher charges for those driving in busy places, in order to reduce noise and congestion. However, this might adversely affect key or shift workers who do not have flexibility when it comes to their working hours.

In response to the 2022 road pricing inquiry, the government signalled that it had no plans to consider road pricing.14 However, from a distributional point of view, road pricing could contribute towards a ‘just transition’ as it does not have to be one-size-fits-all. Rates could still vary according to emissions standards, and other adjustments could be made. For example, there could be annual ‘free’ km allowances and rebates for those on lower incomes. This would make it a more progressive alternative to fuel duty, by taking some of the burden away from those least able to pay. It is also important to note that the negative externalities of not restricting car use—such as increased air pollution or road traffic risk—also disproportionately affect disadvantaged people.15

Public acceptability is generally considered to be a significant barrier to the introduction of road pricing, as it involves the introduction of a new tax and a change to the status quo. People’s aversion to loss is a key challenge when looking to charge for something that is perceived to be free. Most motorists are used to driving where and when they like, and road pricing will be viewed as a significant curtailment of their freedom. Another challenge, related to climate change, is convincing drivers to change their behaviour now, in order to reach a goal that seems very distant (e.g. net zero by 2050). The way in which road pricing is introduced and communicated will play a vital role in the success of any new system.

A well-designed transition period could go some way to alleviating this. It could, for example, include a period in which ICE vehicles continue to pay fuel duty while EVs pay road pricing (at a lower equivalent rate). In the design, it will be important that the cost of running EVs is relatively more attractive to ensure that the overall uptake of EVs is still encouraged. Another avenue to explore is whether private finance, combined with road pricing, could help with funding pressures. It is clear that the government faces a significant challenge to design a new tax system that is both equitable and balances the various competing policy objectives. It is also clear that there is a significant urgency to do this, given the revenue implications of a future without fuel duty.

1 The UK Department for Transport’s (DfT) ‘core’ scenario projects a 22% increase in road traffic between 2025 and 2060 in England and Wales. Source: Department for Transport (2022), ‘National Road Traffic Projections 2022’, p. 7. We note that the governments in Wales and Scotland have introduced targets to reduce the number of car miles in order to reduce traffic and carbon emissions. In Scotland this includes the commitment to reduce car kilometres by 20% in 2030 (against a 2019 baseline). Source: Transport Scotland (2024), ‘20% reduction in car km by 2030’, last accessed 12 March 2024. In Wales, Net Zero Wales sets an aim to reduce the number of car miles

travelled per person by 10% by 2030 (from 2019). Source: Welsh Government (2022), ‘The Future of Road Investment in Wales’, August, last accessed 12 March 2024.

2 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023’, p. 152, Table A.5: Current receipts.

3 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023’, p. 152, Table A.5: Current receipts.

4 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023’, p. 152, Table A.5: Current receipts.

5 HM Revenue & Customs (2022), ‘Introduction of Vehicle Excise Duty for zero emission cars, vans and motorcycles from 2025’, Policy Paper, November, last accessed 13 March 2024.

6 However, it is worth noting that recent forecasts from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) have been scaled back as the steep growth in EV sales in recent years, which was boosted by early (mainly high-income) adopters, is expected to slow in the absence of low-cost EVs. Source: Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Economic and fiscal outlook – November 2023’, p. 90, Box 4.2.

7 Office for Budget Responsibility (2023), ‘Fiscal risks and sustainability’, July, p. 3.

8 We note that this is only the case for households that have access to a car. The proportion of households without a car in 2022, stood at 22% and this includes many households on low incomes. Source: National Statistics (2023), ‘National Travel Survey 2022: Household car availability and trends in car trips’, December, last accessed 13 March 2024.

9 This is based on the DfT’s ‘core’ scenario. Source: Department for Transport (2022), ‘National Road Traffic Projections 2022’, p. 7.

10 We note that in 2018 the government announced that the revenues from VED would be allocated to a new ‘National Roads Fund’ from 2020/21, to pay for major road schemes between 2020 and 2025. However, this commitment has since been abandoned and revenues from VED are not hypothecated but contribute towards general taxation. See UK Parliament (2022), ‘Electric Vehicles: Infrastructure – Question for Treasury’, November, last accessed 13 March 2024.

11 Mayor of London and London Assembly (2024), ‘What will happen to the money raised by the ULEZ?’, last accessed 12 March 2024.

12 However, from April 2025 zero-emission vehicles will also pay VED.

13 Department for Environment Food & Rural Affairs and Department for Transport (2022), ‘Clean air zone framework’, Policy paper, October, last accessed 13 March 2024.

14 House of Commons Transport Committee (2022), ‘Road Pricing; Government Response to the Committee’s Fourth Report of Session 2021-22’, March.

15 Government Office for Science (2019), ‘Inequalities in Mobility and Access in the UK Transport System’, March.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More