Exclusive dealing and foreclosure in EU sports: unpacking the economics in the European Court of Justice’s 2023 Christmas gift

On 21 December 2023, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) pulled the red card for sports associations arbitrarily excluding competing sports organisers in their prior approval rules, acknowledging the potential harm to competition. What does this mean for the future of prior approval rules of sports federations? And how should the potential benefits from these rules be taken into acccount going forward? We provide an economist’s perspective on these cases.

Key points

- The European Court of Justice (ECJ) emphasises that sports federations may not arbitrarily impose exclusive dealing restrictions on their members, as this could deny the public the benefits of competition

- Recognising the conflict of interest in handling both regulatory and commercial activities, the ECJ stops short of requiring structural separation. However, it does require that any prior approval and potential exclusion is transparent, objective and non-discriminatory.

- The ECJ recognises the potential of these measures to serve public interest objectives such as sporting merit and financial solidarity.

- A significant economic question remains: how should, and will, federations weigh these theories of benefit against any anticompetitive harm?

The ECJ released three major judgments on 21 December 2023, on the discretionary power of sports federations under EU competition law.1 The judgments in European Super League (ESL) and International Skating Union (ISU), especially, have caught the attention of many in the competition community. In essence, the ECJ has prevented the football and ice skating federations ‘arbitrarily’ prohibiting clubs and athletes from participating in events that are in direct competition with the federation’s own events.

Within two hours of the judgment being published, A22, the organisation behind the European Super League project that is challenging UEFA and FIFA’s dominance in European professional football, declared victory, stating: ‘We have won the right to compete. European club football is free. The near-70-year UEFA monopoly is finally over’.2

However, UEFA was quick to respond. It blamed the red card on a mere ‘pre-existing technical shortfall’, and emphasised in its press release that the judgment did not, in fact, endorse any super league project.3

So what should we make of these judgments? How might they be seen as a loss to sports federations and their powers and ambitions in the commercial exploitation of sporting events? And how might the judgments nevertheless be seen as a win?

And—looking forward—how do these judgments provide clarity on how to deal with exclusive dealing cases involving sports federations?4

How it all started

At the start of 2021, 12 European football clubs announced their intention to create the European Super League—a new and (semi-)exclusive breakaway league. As an immediate response, UEFA and FIFA threatened to exclude any participating clubs and their players from their own competitions.

Due to broad public resistance to the Super League project, the ESL soon crashed. However, A22—the organisation behind the ESL—still initiated proceedings against UEFA and FIFA in front of the Madrid Commercial Court No. 17, based on the allegation that the statutes of UEFA and FIFA and their threat of sanctions infringed Articles 101 and 102 TFEU. As part of these proceedings, in May 2021 the Madrid Court asked the ECJ for a preliminary ruling on the case. In this, the Madrid Court noted in particular (i) the absence of transparent, objective and non-discriminatory criteria for prior approval of third-party organisers; and (ii) the possible conflict of interest affecting UEFA and FIFA following their dual roles as sports regulator and commercial sports organiser.

The ISU case started in 2014, when two Dutch ice speed skaters lodged a complaint in front of the European Commission. They argued that the ISU infringed EU competition law by preventing them from participating in an unauthorised international speed skating event. In December 2017, the Commission concluded that the ISU authorisation rules harmed competition between sports organisers by ‘creat[ing] significant barriers to finding skaters for third parties wishing to start organising and commercially exploiting international speed skating events in competition with the ISU and its Members’, and that the rules were an infringement of Article 101 TFEU.5 In December 2021, the General Court upheld the decision of the Commission on the anticompetitive effects of the ISU’s so-called eligibility rules, which was confirmed by the ECJ on 21 December 2023.

An economist’s view of the context

Taking a quick step back: from an economics perspective, these cases show three interesting characteristics.

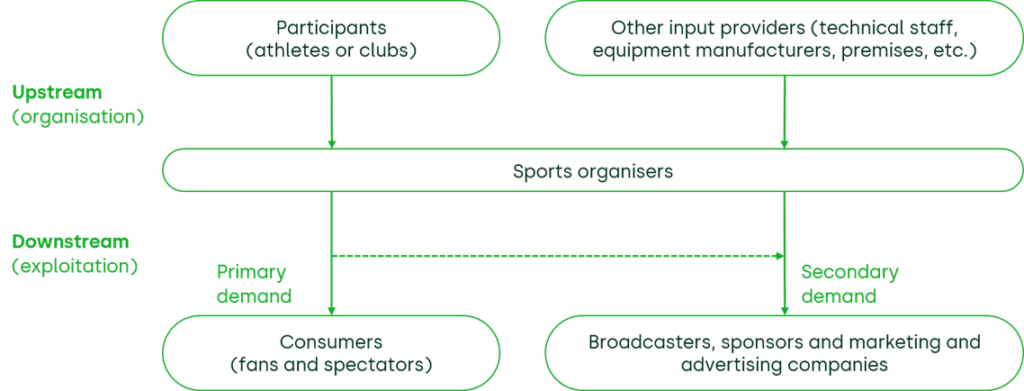

First, the market for the organisation and exploitation of sports can be characterised as a vertical chain (see Figure 1). Upstream there are clubs or athletes that provide their sporting services as input to sports organisers, as well as other input providers (such as technical staff, equipment manufacturers, premises, etc.). Downstream, there is a primary demand for sports events by consumers (fans and spectators), as well as a secondary demand by broadcasters, sponsors and marketing and advertising companies. This is a secondary demand because it is ‘derived’ from the primary demand from consumers.6

This market definition reveals that a sports organiser may actually be dominant in one relevant market (e.g. the purchasing of club or athlete services; or consumer attention), but not in another (e.g. consumer attention, or broadcaster and sponsorship services).

Figure 1 Vertical market structure for sports

Source: Oxera (2023), ‘Striking a balance: legal and economic scrutiny of exclusive dealing in EU sports’, Agenda, 30 June.

Second, the prior approval rules in ESL and ISU can be equated to exclusive dealing restrictions: absent the prior approval of third-party sports organisers, clubs or athletes are not allowed to provide their sporting services as an input to these third-party organisers. In essence, this is standard input foreclosure by a dominant buyer of upstream services.

Third, where the sports federations are controlled by clubs or athletes, this can be characterised as a vertically integrated undertaking. Again, this comes with standard concerns around input (or, indeed, customer) foreclosure.

Depriving the public of competition

The ESL and ISU judgments are clearly a step in the right direction. From an economics perspective, it makes a lot of sense to prohibit any dominant firm—which includes most sports associations—from arbitrarily excluding competitors through exclusive dealing restrictions or other types of input foreclosure.

However, it is important to really recognise why this makes sense. As mentioned by the ECJ, the organisation of sport is, ‘quite evidently’, an economic activity7—and economic activities thrive under competition, for the benefit of consumers and other stakeholders. That is why we subject them to Article 101 and 102 TFEU.

In the context of sports, competition can benefit downstream customers—for example, by decreasing prices for viewers and fans, increasing output or quality through more high-calibre matches or innovative formats, or creating more opportunities for sponsorship and broadcasting.

Competition can even benefit upstream input providers—and particularly the clubs and athletes. Generally, sports federations are democratic representations of sports participants, and one might therefore expect that the interests of these upstream input providers are taken into account. However, even sports federations may start neglecting the benefits to their members when pursuing commercial objectives—in particular when there are no alternatives to their members.

Or, as the ECJ puts it in ESL (and similarly in ISU):8

[These prior authorisation rules] completely deprive professional football clubs and players of the opportunity to participate in those competitions, even though they could, for example, offer an innovative format whilst observing all the principles, values and rules of the game underpinning the sport. Ultimately, they completely deprive spectators and television viewers of the opportunity to attend those competitions or to watch the broadcast thereof.

This raises the question of whether one can really characterise the arbitrary exclusion of competitors as a mere ‘pre-existing technical shortfall’—as UEFA has done. Exclusive dealing deprives the public of the benefits of competition, and you really need to have good reasons for doing this, especially when you are dominant.

However, it is not all a loss for the sports federations. There are at least two fields on which sports federations can claim a victory.

Referee, or player?

First, sports federations can take solace—even claim a victory—from the fact that the ECJ does not actually question the legitimacy of the sports regulator as a concurrent organiser of commercial sporting events.

This was not an obvious outcome. Structural separation between the regulatory function of federations and the commercial exploitation of sports events has been proposed. It is not difficult to see why. As the ECJ recognises in both ESL and ISU:9

To entrust an undertaking which exercises a given economic activity the power to determine, de jure or even de facto, which other undertakings are also authorised to engage in that activity and to determine the conditions in which that activity may be exercised, gives rise to a conflict of interests and puts that undertaking at an obvious advantage over its competitors

However, in response to this conflict of interest, the ECJ does not actually call for a structural separation. It does not even consider the legal or economic merits of this. Instead, it ‘merely’ demands for that power to be exercised in a way that is transparent, objective, non-discriminatory and proportionate.

In other words, sports federations may continue to impose prior authorisation rules that could lead to the exclusion of direct competitors—provided that this is done in a transparent, objective and non-discriminatory way and with sanctions that are proportionate.

Objective justifications

As a second win for sports federations, the ECJ recognises that—at least in principle—there may be objective justifications for sports federations to impose restrictive prior authorisation rules, even if these rules could distort competition. In particular, in ESL the ECJ notes the following:10

In the present case […] the Court finds that [prior authorisation] may be justified, in terms of its very principle, by public interest objectives consisting in ensuring, prior to the organisation of such competitions, that they will be organised in observance of the principles, values and rules of the game underpinning professional football, in particular the values of openness, merit and solidarity, but also that those competitions will, in a substantively homogeneous and temporally coordinated manner, integrate into the ‘organised system’ of national, European and international competitions characterising that sport.

In other words, prior authorisation in football may be justified when there are public interest objectives such as (i) open competitions based on sporting merit; (ii) financial solidarity; and (iii) a sufficiently ‘organised system’ of national, European and international competition.

Separately, although not discussed in these judgments, exclusive dealing restrictions may be necessary to prevent opportunistic freeriding behaviour by clubs or athletes. Particularly when a sport is nascent, a sports organiser may have to invest a lot in developing the sport and its clubs or athletes. In the absence of any restrictions on clubs or athletes on then switching to alternative organisers once the sport has reached a certain scale, the original incentive to invest may be undermined.

In short, the ECJ recognises that exclusive dealing restrictions in sports have the potential to be both a force for evil (foreclosing competition and depriving the public of its benefits) and a force for good (protecting legitimate public interest, or indeed economic objectives such as the prevention of freeriding behaviour).

Mind the (economics) gaps

On the one hand, the ECJ therefore recognises that exclusive dealing in sports comes with clear potential theories of harm and that dominant sports federations have an obvious conflict of interest when determining their prior authorisation rules.

On the other hand, the ECJ bestows sports federations with the right to commercially exploit the sport, as well as the legitimacy to impose prior authorisation rules. Moreover, it recognises that such rules can be used to pursue legitimate objectives. However, this raises some important questions of economics.

Gap 1: how to balance different, potentially conflicting, objectives

As discussed above, the ECJ suggests several potential objective justifications beyond purely economic pursuits. However, it does not actually provide any guidance on how to weigh these different objectives against each other, or against any anticompetitive harm.

Instead, it concludes that (i) the absence of transparent, objective and non-discriminatory rules itself is sufficient to conclude on an infringement ‘by object’; and (ii) by-object infringements cannot be justified by any pursuit of potentially legitimate objectives, even if it is proportionate (i.e. the ‘ancillary restraints doctrine’ following the Wouters judgment).11

So does that mean that, if sports federations put in place rules that are transparent, objective and non-discriminatory, they can be evaluated under the ancillary restraints doctrine?

And if so, how will this doctrine ensure that all harms from excluding competitors are sufficiently weighted against the benefit of pursuing a legitimate objective for which the restraints are considered ‘necessary and proportionate’? What risk is there that the ancillary restraints doctrine will effectively become a get-out-of-jail-free card for sports federations?

Or, if the ancillary restraints doctrine does not apply, how should the objective justifications be evaluated under, in particular, an Article 101(3) TFEU efficiency defence? Is there a risk that the strict conditions under 101(3) will be seen to be too strict—and not properly accommodative of the special characteristics of sports?

Irrespective of the legal framework, the economics toolkit may help to articulate the various effects in a coherent way, and may even be able to assist in quantifying some of these.

Gap 2: how to ensure that balancing is done properly, given the private interests involved

It remains unclear exactly how sports federations will end up conducting this balancing exercise—given that they still have the conflict of interest.

Granted, sports federations are now obliged to impose rules that are non-discriminatory. They cannot impose standards (related to public policy objectives or otherwise) on competitors that are any different from the standards that they themselves need to adhere to.

This is good: no dominant firm should be allowed to impose different standards on its competitors to those that it adheres to itself.

However—and as also recognised by the ECJ—even if standards are identical or similar, they may still be ‘impossible or excessively difficult to fulfil in practice for an undertaking that does not have the same status as an association or does not have the same powers at its disposal as that entity’.12

It will be interesting to see exactly what room this allows for sports federations such as UEFA and FIFA to devise prior authorisation rules that are non-discriminatory in form, but just as exclusive in practice—particularly in light of a new Super League proposal by A22: an open competition with admission based on sporting merit, higher solidarity payments, and free streaming for fans.13

To be continued.

1 Case C-333/21: European Superleague Company SL v Union Federaciones Europeas de Futbul (UEFA), Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA), 21 December 2023; Case C-124/21 P: International Skating Union v Commission, 21 December 2023; Case C-680/21: SA Royal Antwerp Football Club v Union royale belge des sociétés de football association ASBL (URBSFA), 21 December 2023.

2 A22 Sports Management (2023), ‘A22 proposes new open European competition’, press release, 21 December.

3 UEFA (2023), ‘UEFA statement on the European Super League case’, press release, 21 December.

4 For more background, including a discussion of the Opinion from Advocate General Rantos that preceded the ECJ judgment, see Oxera (2023), ‘Striking a balance: legal and economic scrutiny of exclusive dealing in EU sports’, Agenda, 30 June.

5 European Commission Case AT.40208 ISU’s Eligibility Rules, 8 December 2017, Decision, para. 4.

6 For more on market definition in markets involving the organisation and commercial exploitation of sports events, see Klein, T. (2023), ‘Exclusive dealing in sports after ESL and ISU’, working paper, SSRN 4351680.

7 European Court of Justice (2023), ‘The FIFA and UEFA rules on prior approval of interclub football competitions, such as the Super League, are contrary to EU law’, press release no 203/23, judgment of the Court in Case C-333/21 European Superleague Company, 21 December.

8 ESL, para. 176; and ISU, para. 146.

9 ESL, para. 133; and ISU, para. 125.

10 ESL, para. 253.

11 See ESL, para. 183; and ISU, para. 111 for a summary of the case law. We note that this last point (i.e. that the ancillary restraints doctrine would not apply to by-object infringements) has already sparked a separate legal debate—with some referring to it as ‘arguably self-evident’ (Colomo, P.I. (2024), ‘On Superleague and ISU: the expectation was justified (and EU competition law may be changing before our eyes)’, Chillin’Competition, 21 December), and others stating that ‘there is no precedent to support this and the position is illogical’ (Monti, G. (2024), ‘EU Competition Law after the Grand Chamber’s December 2023 Sports Trilogy: European Superleague, International Skating Union and Royal Antwerp FC’, working paper, SSRN 4686842, p. 18).

12 ESL, para. 151; and ISU, para. 133.

13 A22 Sports Management (2023), ‘A22 proposes new open European competition’, press release, 21 December.

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Company valuation in post-M&A disputes—the Mahtani v Atlas Mara ruling

Post-merger and acquisition (‘post-M&A’) disputes can take many different forms, such as breach of representations and warranties, fraud and misrepresentation claims, and post-completion breach of contractual obligations. This article discusses the valuation issues in a post-completion breach case based on the ruling handed down by the Hon Mr Justice Butcher… Read More