Fighting inflation with competition: the right tool for the job?

The prices of many goods and services are increasing—but so are corporate profits. In the context of a recent rise in the cost of living, we dissect the alleged role of market power, and failing competition, in driving inflation. To what extent are inflation and rising profits simply macroeconomic phenomena? Or is there a role for microeconomics and competition policy in our collective fight against rising prices?

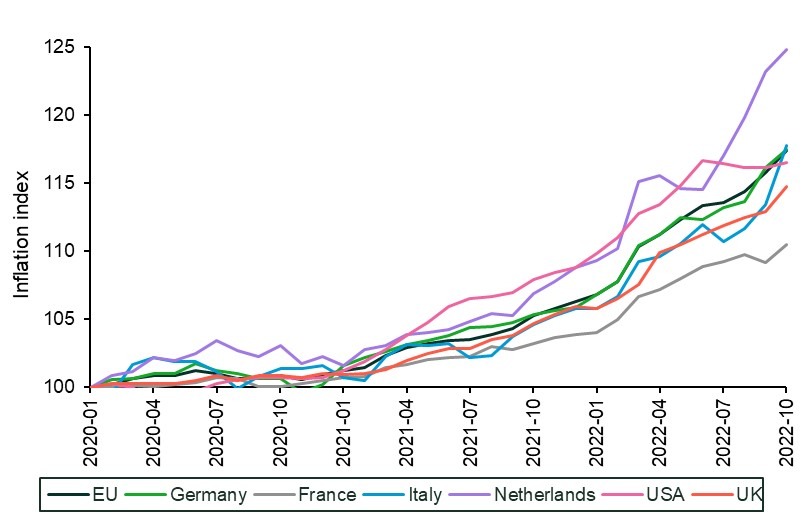

Since early 2021, prices have been rapidly increasing worldwide. To put this into perspective: goods that were worth €100 in January 2021 would cost you €115 in December 2022 (on average—see Figure 1).

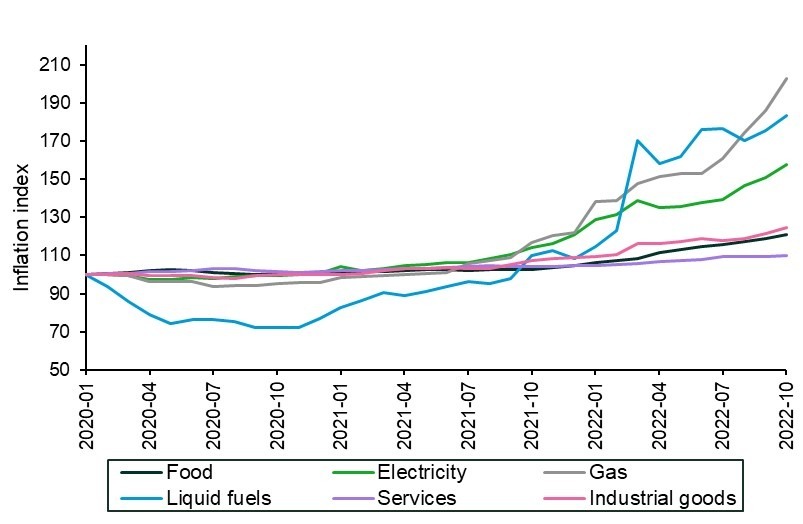

This increase in prices is driven largely by higher energy prices, with the price of electricity, gas and liquid fuels increasing between 50% and 100%. However, food, services and industrial goods have also increased by more than 10% since January 2021. The same amount of money is simply buying you less as time progresses (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Inflation index by country (2020–22)

Source: Eurostat.

Figure 2 EU inflation index by industry (2020–22)

Source: Eurostat.

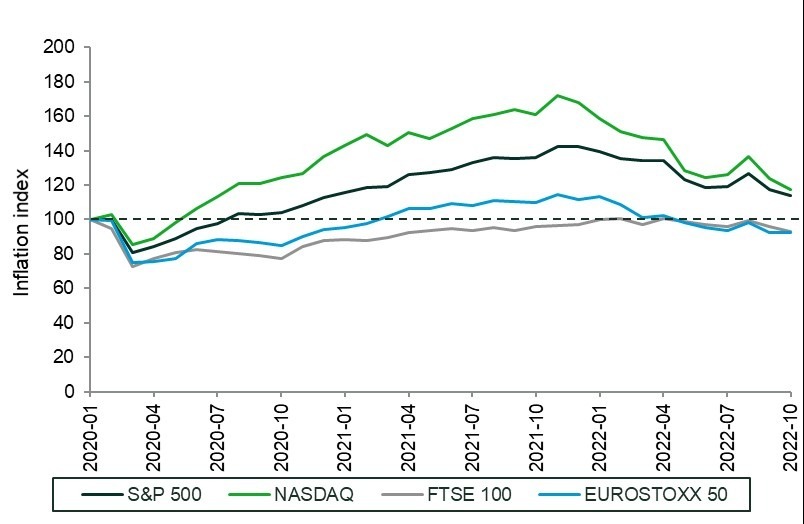

At the same time, corporate profits remain high. Although global stock prices have taken a hit in 2022, they generally remain at—or even above—their pre-COVID-19 levels, despite the high levels of inflation.

Note that stock prices are a present-day valuation of the current and future profitability of firms, and, as money becomes less valuable because of inflation, the present-day valuation of future profitability should decrease.

Figure 3 Major stock exchange indices (2020–22)

Source: Boursorama.

To what degree can the rise in prices and profits be ascribed to corporate power and failing competition? Are companies exploiting market power and undermining fair competition? Or are price increases—and profits—driven by external shocks that are outside of the control of companies?

Some make a link between inflation and failing competition. For example, in November 2021, the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) opened an investigation into the ‘market conditions and business practices’ that may have worsened supply-chain disruptions and increased prices.1 And in May this year, Matthew Boswell, the Canadian Commissioner of Competition, stressed that ‘competition has to be part of the solution [to inflation]’.2

In addition, during the EU Competition Day in Prague on 10 October 2022, Executive Vice-President Margrethe Vestager stressed that ‘[p]eople see the cost of living crisis caused by very high inflation. It is important that there is competition so that no one can take advantage of this situation’.3

Others are more sceptical. For example, both the UK Competition and Markets Authority and the French Autorité de la concurrence (which is currently led by Benoît Cœuré, former board member of the European Central Bank) have openly voiced scepticism that competition policy can be used in any meaningful way to fight inflation.4

In this article, we unpack the debate around the link between rising inflation and competition policy. Why is inflation not principally caused or resolved by competition policy? And how might competition policy—and the microeconomics underlying it—still have an important role to play in fighting this macroeconomic phenomenon?

Fighting macro problems with micro tools

The macroeconomics of inflation

It is generally recognised that falling competition is not the root cause of current inflation. Rather, the cause is seen as being excess demand and disrupted supply.

The International Monetary Fund recognises four key causes of inflation:5

- demand shocks (or ‘demand-pull’ inflation), where the sudden availability of extra expenditure (e.g. because of excess savings, lower central bank interest rates, or increased government spending) boosts demand beyond current capacity levels;

- supply shocks (or ‘cost-push’ inflation), where sudden scarcity in an input (e.g. a fuel or other raw material) increases the price of all goods and services that rely on it;

- lax monetary policy and an excessive supply of money available in an economy;

- expectations, where people or firms may anticipate higher prices in the future, and build those into their wage negotiations and contractual price adjustments, making the expectations of price increases self-fulfilling (potentially even resulting in a ‘wage–price’ spiral).

In the context of the current inflation crisis, there is a clear case for both demand and supply disruptions pushing up price levels.

On the demand side, many households have deferred spending during the COVID-19 pandemic, bringing savings rates to record highs.6 Moreover, governments have been generous in supporting households and businesses throughout the pandemic, which caused many households to have excess spending capacity once the world reopened.

On the supply side, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted many production facilities, as well as trade flows, leading to global supply-chain disruption. Moreover, the Russian invasion of Ukraine earlier in 2022, and the subsequent sanctions against Russia, have caused the price of oil and gas to skyrocket—feeding through to energy costs, petrol pump prices, and many supply chains.

Both of these disruptions have also worked to increase corporate profits in some sectors such as petrol7—which may help to explain the recovery and the moderate decline in global stock prices, despite surging inflation.

Taking these causes (demand- and supply-side disruptions) into account, the textbook response to rising inflation is straightforward:

- reduce the overall money supply;

- dampen demand through increases in central bank interest rates (i.e. monetary policy) or increased government taxation and/or reduced spending (i.e. fiscal policy);

- aim to fix supply chain disruptions;

- manage expectations of future inflation.

In short, both the root causes and textbook responses to inflation are principally macroeconomic phenomena—they deal with general economic factors that apply to the economy as a whole.

The microeconomics of competition policy

In contrast, competition policy remains a microeconomic tool. It is applied case by case, taking into account the specifics of a clearly delineated product and geographic market, and the incentives faced by the various parties (usually a limited number of large competitors). Inflation, on the other hand, occurs in a broad range of products and geographies.

Additionally, competition policy cases can take months, sometimes years, before a decision is made.8

The way in which competition policy is implemented across the globe is also a relative constant, changing course only gradually—like an oil tanker. The current levels of inflation, however, have been sudden and sharp.

Moreover, there does not appear to be a clear relationship between the degree of market concentration (as a proxy for the degree of competition) and inflation. For example, one of the markets suffering the highest inflation in the USA is that for second-hand cars. Between February 2020 and September 2022, average prices rose by around 42.5%.9 At the time, the market for second-hand cars was one of the least concentrated in the USA, with the ten largest suppliers covering less than 10% of the market.10

More market power, less inflation?

More market power implies higher price levels. However, inflation is about the change in prices. While market power may explain why price levels are high, it does not explain how price changes are passed on through the economy.

Intuitively, one might assume that a firm with a lot of market power would pass through more of the increase in any of its input costs to downstream customers. If so, that would imply that in concentrated markets—with fewer but more dominant firms—inflation would be worse. A smaller proportion of any upstream cost increase would be absorbed by firms, and a greater proportion would end up with their downstream market—this being either direct customers or an intermediary firm.

However, fundamental microeconomic theory shows that this intuition is wrong. In fact, the exact opposite relation holds: when firms have more market power, they will instead absorb more in case an upstream cost increases—and therefore downstream inflation will be lower.

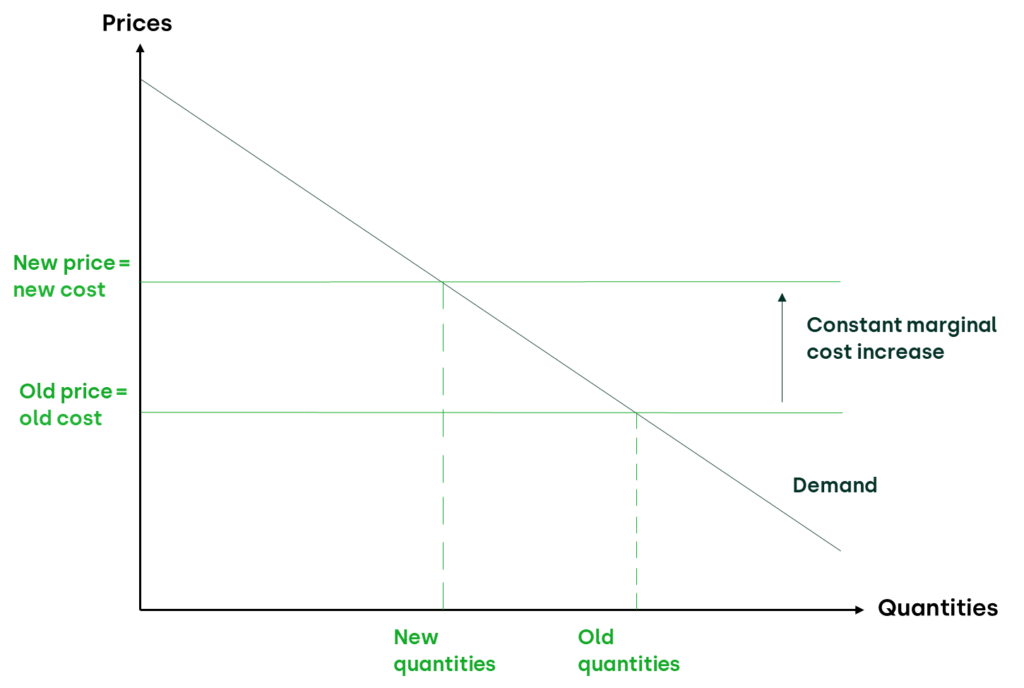

This can be explained as follows: when firms are operating in a highly competitive landscape, they will have no choice but to set prices close to cost, as doing otherwise would mean that competitors are able to easily steal customers away by setting slightly lower prices. With market prices closely tracking cost levels, any increase in a common industry cost will in turn push up market prices by nearly the same extent (see Figure 4).

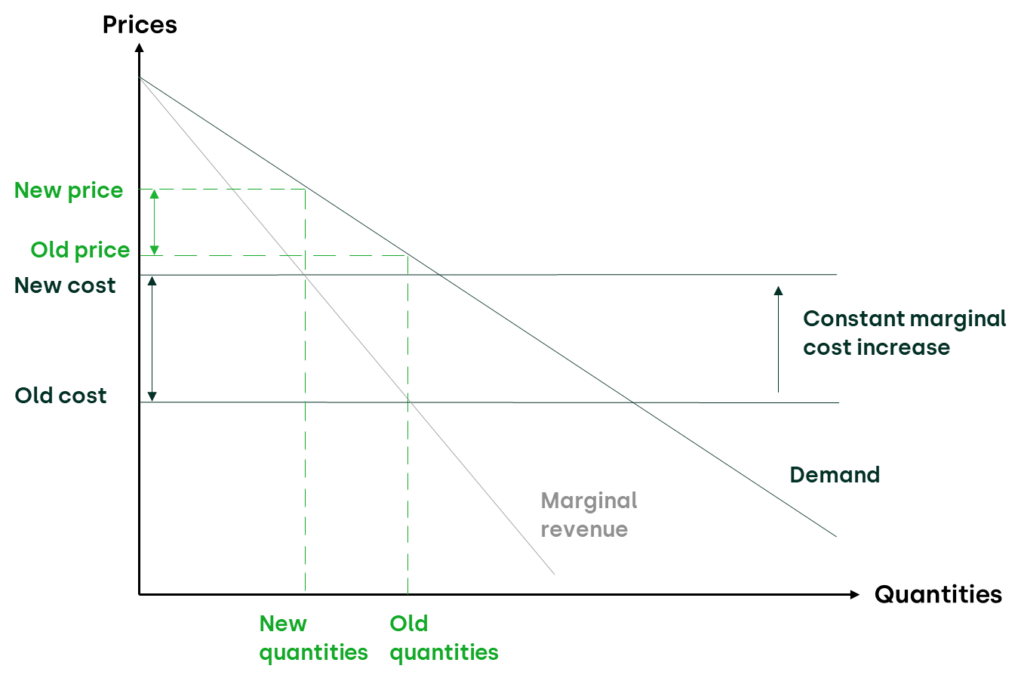

In contrast, when firms have market power and are currently selling at a large mark-up, they have the ability and incentive to absorb some of the cost increase, and keep the increase in prices limited—so as not to excessively disrupt overall demand (see Figure 5).

Figure 4 Effect of constant marginal cost increase on prices under perfect competition

Source: Oxera.

Figure 5 Effect of constant marginal cost increase in a monopolist market

Source: Oxera.

While this theoretical relationship between market power and cost pass-through has long been recognised, Christos and Pagliero (2022) show that this relationship also holds empirically—at least in one setting.11 Looking at regionally separated retail gasoline prices in small Greek islands following a common tax increase, the paper finds that pass-through in monopoly markets is around 40%, while it is around 100% in markets with four or more competitors. Moreover, the paper shows that the speed of price adjustment is around 60% higher in competitive markets than in monopoly markets.

In short, microeconomics tells us that more market power implies higher price levels—but also lower price changes when costs get passed on through the supply chain. More market power, while harmful to consumers in terms of higher price levels, also implies a dampening of any upstream inflation for downstream customers.

How can competition policy help?

If inflation is predominately a macroeconomic phenomenon and there is no clear microeconomic basis for blaming inflation on market power, does competition policy still have a role to play?

We conclude that, even if failing competition policy is not the root cause of inflation, and competition policy is not a textbook response, there are still important ways in which competition authorities can be part of the solution.

Competitive markets keep prices low

Even if more market power implies a dampening of pass-through inflation, it also implies structurally higher price levels. As such, invigorating competition policy can help to bring down price levels.

The European Commission itself claims that, over the period 2012–20, competition policy enforcement in the EU has reduced the EU’s overall price level by 0.63 percentage points.12

At the same time, a generic call for ‘more’ competition policy is unlikely to be very effective. Even if overall market power has increased beyond acceptable levels, and competition policy in general has been too lenient, competition investigations remain a tool that should be applied case by case.13

Market power leads to more rationing under positive demand shocks

Moreover, even if more market power implies a dampening of inflation following an upstream supply shock, the opposite may actually hold in the case of a positive demand shock (e.g. because of the excess savings or government spending during the COVID-19 pandemic).

As shown by Menezes and Quiggin (2022), firms with market power have a larger incentive to limit the supply of goods in the event of a positive demand shock.14 This is because firms with more market power benefit more from rationing than firms with less market power—and this benefit from rationing becomes greater when overall demand is higher.

Based on this rationing theory of harm under positive demand shocks, higher levels of market power lead to even more inflation.

However, the exact type of competition law infringement that this ‘rationing theory of harm’ may represent is unclear. As long as firms keep setting their capacities independently, and without coordinating with competitors, there is no clear infringement of competition law. Firms benefit from the situation, but this pursuit of individual profits is what we would expect firms to do—as long as it does not constitute an abuse of dominance through excessive pricing. Competition law (generally) does not expect commercial entities to sell more and at lower prices just because it is in the public interest.

Inflation may lead to coordinated price rises beyond cost

In periods of high inflation, prices change frequently. This makes it difficult for firms to anticipate the prices that rivals will be charging, and for firms to coordinate on particular prices.

However, not everyone agrees that this is the end of the story. Lina Khan, chairwoman of the FTC, has stated that ‘an inflationary environment can give cover to companies with market power or monopoly power to exploit that power’.15 Similarly, a recent economics paper has found that a crisis period may be a factor triggering firms to coordinate.16

Put differently, there may be a risk that inflationary pressures can be used or abused somehow by firms to increase their price either unilaterally or in a coordinated way.

Usually, colluding firms must come to a common agreement about which price or price increase to implement. During a period of inflation, the inflation rate may be used by firms as a focal point for price rises, facilitating the creation of a common agreement.17

However, there are two important nuances to this theory of harm.

First, there is no clear empirical evidence to date that firms are using inflation as a cover to coordinate their price increases above their own inflation rates (either explicitly or tacitly).

Second, inflation may make collusion less rather than more sustainable. The reason for this is that inflation reduces the importance of future profits relative to present profits. This, in turn, may shift the balance in favour of short-term profits due to undercutting your own competitors, thus breaking up the collusive scheme and rendering it unsustainable.18

The (modest) role of competition policy

Inflation is, first and foremost, a macroeconomic phenomenon. Its root causes and textbook responses are principally macroeconomic tools. In contrast, competition policy remains a microeconomic tool that is applied on a case-by-case basis.

Nevertheless, competition policy has a role to play when fighting inflation. Market power and high concentration levels may not be directly responsible for the current rates of inflation. However, maintaining market competition can still help to keep price levels down and dampen the inflationary effect from positive demand shocks.

Moreover, competition authorities must remain particularly vigilant in ensuring that firms are not abusing the current inflationary period by coordinating their price rises beyond the ongoing cost increases.

During a roundtable on this topic held on 30 November 2022, OECD Secretary-General Mathias Corman concluded that:19

Competition contributes to reducing long-run inflationary pressures and prevents anti-competitive behavior from exacerbating inflation. However, it should not be expected from competition agencies to solve the current inflationary pressures in the short term given some of the underlying causes: a series of highly exceptional supply shocks.

And in a statement in October 2022, the International Competition Network concluded that:20

Although inflation typically is the result of much broader factors, competition may make a difference by accelerating the adjustment of supply and demand to changing market conditions that are caused by inflation. Competition boosts economic growth and wages, which may help consumers to recover purchasing power lost due to inflation. Strong competition enforcement can prevent firms from using inflation as a cover for anticompetitive price increases and can also prevent mergers that would lead to price increases and make the effects of inflation worse. Opening up competition in sheltered sectors can reduce barriers to entry and translate into lower prices, hence giving back purchasing power to consumers.

Inflation is not principally driven or solved by competition policy. However, the competition community is starting to recognise that competition policy has a role to play in combating the cost-of-living crisis.

1 Federal Trade Commission (2021), ‘FTC Launches Inquiry into Supply Chain Disruptions’, press release, 29 November.

2 Boswell, M. (2022), ‘Building a More Competitive Canada’, speech at the Centre of International Governance Innovation, 26 May.

3 Vestager, M. (2022), ‘Fairness and Competition Policy’, speech at the EU Competition Day, Prague, 10 October.

4 Politico (2022), ‘Europe wary of following U.S. in using competition policy to fight inflation’, 8 February.

5 International Monetary Fund, ‘Inflation: prices on the rise’, (accessed 15 December 2022).

6 For example, EU-wide household savings grew from 5–6% of disposable income in 2016–19 to 13% in 2020. In UK they grew from -1–1% in 2016–19 to 10% in 2020, and in the USA they grew from 7–8% in 2016–19 to 17% in 2020. See Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2022), ‘Household savings’ (accessed 14 December 2022).

7 Reuters (2022), ‘Oil giant’s massive profits revive calls for windfall taxes’, 28 October.

8 For example, the OECD found that the average duration of an international cartel investigation is around 2.8 years. See Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2020), ‘OECD Competition Trends’.

9 JPMorgan Chase & Co. (2022), ‘Inflation and the Auto Industry: When Will Car Prices Drop?’, 14 November.

10 Mobility Foresight (2021), ‘Used Car Market in US 2021-2026’. However, this concentration level does not actually look at the most appropriate product and geographic market, and there may be higher concentration levels in specific markets that are smaller and constitute only actual substitutes. Moreover, the second-hand car market is linked to the market for new cars, which is more concentrated.

11 Christos, G. and Pagliero, M. (2022), ‘Competition and Pass-Through: Evidence from Isolated Markets’, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 14:4, pp. 35–57. In contrast to this paper, however, a recent study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston shows an opposite direction between market concentration and pass-on (i.e. that more concentrated industries pass on more costs). Brauning, F., Fillat, J.L. and Joaquim, G. (2022), ‘Cost-price relationships in a concentrated economy’, Current Policy Perspectives, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Research Department, 23 May. However, this second study does not look at antitrust markets, but at markets based on their three-digit NAICS code—which is known to lead to market definitions that are either too wide or too narrow.

12 European Commission (2022), ‘Modelling the macroeconomic impact of competition policy: 2021 update and further development’, March, p. 3.

13 In addition, the presence of competition authorities may have a deterrent effect on cases that they do not investigate. For example, the UK Competition and Markets Authority has found ‘good evidence of the existence of a substantial deterrent effect from competition authorities’ actions’. See Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘The deterrent effect of competition authorities’ work: Literature review’, 7 September. For the quantification of this effect, see Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘CMA Evaluation of CA98 cases’, May.

14 Menezes, F.M. and Quiggin, J. (2022), ‘Market power amplifies the price effects of demand shocks’, Economics Letters, 221:110908. The authors found that, in a competitive market, firms price at marginal cost. Since marginal cost does not change following a demand shock, firms do not change their prices. Hence, rationing makes no economic sense as profits do not increase.

15 Politico (2022), ‘Europe wary of following U.S. in using competition policy to fight inflation’, 8 February.

16 Stephan, A. (2021), ‘The Price Fixer: Compliance Tales from the Other Side’, CCP Working Paper 21-06, forthcoming as a book chapter in A. Riley, A. Stephan and A. Tubbs (eds), Perspectives in Antitrust Compliance, Concurrences.

17 For example, three firms operating in an industry that is subject to a 3% inflation rate, while the national inflation rate is 6%, may recognise (with no or perhaps limited communication) that it is in their shared interest to all increase prices by 3% rather than 6%.

18 Collusion essentially involves forgoing high short-term profits from undercutting your competitors in return for higher long-term profits under the collusive scheme relative to competition. Inflation may, however, change this balancing in favour of short-term profits from undercutting your competitors. The reason for this is that inflation reduces the importance of future profits relative to present profits. For example, €100 profits today allows you to buy €100 of goods, while €100 profits in the future will allow you to buy 100*(1+0.1) = €90.1 of goods in the future.

19 MLex (2022), ‘Don’t expect competition watchdogs to solve short-term inflation problems, OECD head says’, 1 December.

20 International Competition Network (2022), ‘The Role of Competition & Competition Policy in Times of Economic Crisis’, ICN Steering Group Statement, October. The International Competition Network represents different national and regional competition authorities across the world. Its objective is to discuss practical competition concerns and informally advise competition authorities.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More