Financial resilience: demonstrating long-term viability for utilities

Company failure can impose costs on customers as well as society more broadly. To mitigate this, regulators have in recent years subjected companies’ business models to increased scrutiny to enable a broader set of stakeholders to assess risks to financial viability. Stress-testing has been embedded in the banking sector and is increasingly being used elsewhere—such as in the UK water sector.

The importance of financial resilience goes beyond the financial sector—in 2014, the UK Financial Reporting Council (FRC)1 amended the Corporate Governance Code to require all listed companies to provide a clearer and broader view of the risks affecting their long-term viability:2

the directors should explain in the annual report how they have assessed the prospects of the company, over what period they have done so and why they consider that period to be appropriate. The directors should state whether they have a reasonable expectation that the company will be able to continue in operation and meet its liabilities as they fall due over the period of their assessment.

In its latest review of corporate reporting,3 the FRC went further and recommended that companies improve disclosure of the processes followed in their risk analysis, as well as assumptions made in arriving at their viability statements. Some companies already disclose information on processes, parties involved, stress-testing methodologies, and a range of assumptions used—thus setting an example that the FRC wishes other companies to follow.

In the banking sector, risk analysis is conducted and disclosed in accordance with the stress-test framework developed by the Bank of England, with similar frameworks operating in coutries around the world.4 These stress tests are conducted annually and reflect a range of scenarios.

While the focus on financial resilience has been greatest in the financial sector, the topic is rising up the agenda in other sectors. Stress-testing in the financial sector is particularly important because of the wider systemic consequences of bank failure. However, company failure in any industry can impose costs on customers and society. Failure of utilities could be particularly costly, given the importance of the public service that they provide, and therefore minimising the risk and consequences of failure is a key concern of economic regulators.

For example, Ofwat, the economic regulator of the water industry in England and Wales, has introduced a number of corporate governance principles to which all water companies are required to adhere (see the box below). These principles were intended to increase trust, confidence and transparency in a sector that provides an essential public service. The regulator also stated that it is reasonable for customers to expect companies to operate under high governance standards.5

Principles of corporate governance introduced by Ofwat

- The number of executive directors on the Board should be no greater than the number of independent directors

- The majority of directors on the audit and remuneration committees should be independent

- The Chair must be independent of management and investors

- Reporting must meet or exceed the standards set out in the Disclosure and Transparency Rules for listed companies1

- The regulated company must act as if it is a public listed company that is separate from the holding company—for example, board committees should operate at the regulated company level

- The group structure must be explained in a way that is clear and simple to understand

Note: Following Ofwat’s publication in 2014, these principles were reflected in the water companies’ licences. 1 For example, see the latest rules in Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Disclosure Guidance and Transparency Rules sourcebook’, October.

Source: Ofwat (2014), ‘Board leadership, transparency and governance – principles’, January.

In areas where the activities of the holding company could affect the regulated water company, Ofwat also introduced a number of principles for the former, including increased transparency of its structure; assurance that the regulated company is protected from risks elsewhere in the group; and support for the regulated company to operate in a sustainable way in the long term.6

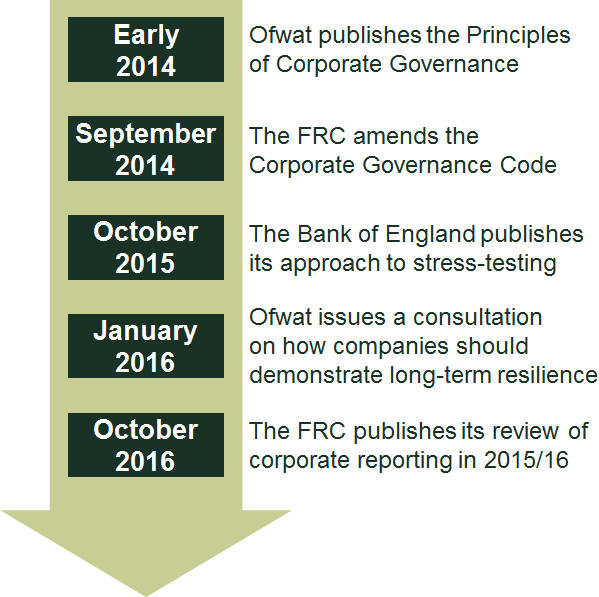

In 2016, Ofwat issued a consultation on how water companies should demonstrate long-term financial resilience.7 Consistent with the FRC’s recommendations later in the same year, the regulator proposed that water companies should stress-test their financial plans and ‘include an explicit statement in both their statutory and regulatory accounts’8 that would describe the processes followed in those tests. The onus will therefore be on the companies to assure investors, consumers and regulators that their boards have taken an informed decision when making a statement about their long-term financial viability. The first series of such statements was published as part of annual accounts for the 2015/16 financial year. Figure 1 presents recent decisions by Ofwat and the FRC in this area.

Figure 1 Timeline of decisions on corporate governance by Ofwat and the FRC

In addition to Ofwat’s requirements, utilities in the UK often have explicit requirements in their licence conditions to maintain a certain credit rating.9 While the required credit rating might differ among firms, in general it means that these companies need to consider risks that could potentially lead to a rating downgrade—i.e. any changes in the level of their financial viability.

What does this mean for the water sector?

While water companies typically maintain risk registers, their actual modelling varies and can be limited to a small number of scenarios with medium impact and probability, such as an increase in financing or pension costs, or a large and sustained decrease/increase in the inflation rate.

It is important to remember that the aim of a stress-test exercise is to assess the company’s resilience to a range of adverse shocks, and identify measures to ensure that it would be able to withstand these. Ofwat therefore expects the water companies to include the impact of severe but plausible scenarios in their modelling. For this reason, it is likely that the sector will need to go much further than the current practices. Events with a potentially large impact but relatively low probability (such as adverse Brexit scenarios) are currently mostly absent from the companies’ analyses but may need to be considered in future.

Following Ofwat’s consultation in early 2016, the FRC, in its latest review of corporate reporting of listed companies, has stated that listed companies should model risks associated with the broader environment in which they operate (in addition to conducting more traditional analysis of operational and financial risks). This could, for example, include potential future limitations on the range of tax strategies that a company can adopt, given that public and media interest in corporate tax arrangements could in future mean that the government deems some strategies unacceptable. Another risk to consider would be the potential impact of climate change—for example, the Financial Stability Board10 is currently developing voluntary guidelines on disclosure of climate-related financial risks and will publish its findings by the end of 2016. Companies across the utilities sector may wish to consider how to adapt their analysis to reflect this broader requirement.

Finally, the stress-test exercise is not just about modelling individual shocks but also about the potential interdependencies of these shocks and the probability of their occurrence. The latter is less commonly reflected in companies’ practices and would therefore require an expansion of the modelling approach.

How should water companies respond to the current and future changes?

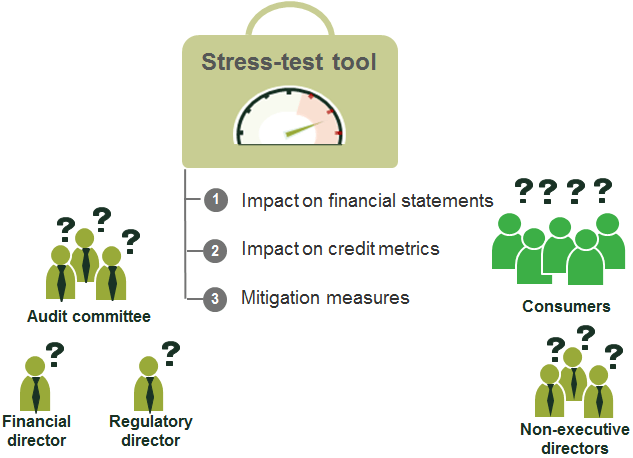

So how can water companies demonstrate that they comply with the new requirements? Ofwat has not yet specified how to undertake a stress-test exercise and has instead invited all parties to put forward proposals. This puts the onus on water companies to form a view on issues such as the definition of financial viability, the length of the period, the relevant credit metrics, appropriate mitigation measures, and how these factors are tailored to their particular business.

In relation to the length of the assessment period, the FRC has reported that most public companies currently choose a three-year time horizon, although only some give reasons for this. The FRC has highlighted that this period should not become a default option and that management should ‘give adequate thought to their company’s particular circumstances’.11 At the same time, Ofwat has clearly stated that it expects water companies to consider their viability both within and beyond the current price control period. This means that all listed companies in general, and water companies in particular, will need to carefully consider the assumptions they use in the analysis and make sure that these are clearly explained in their annual reports.

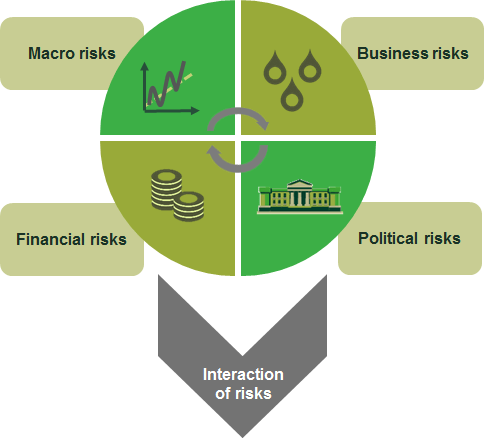

The second step (Figure 2) is for water companies to identify the set of risks to model. According to the FRC, the general focus should be on determining the nature and scale of the principal risks faced by the company, including those that the company is willing to take in order to achieve its strategic objectives. While the precise set of risks will differ across firms, all modelled risks need to be both measurable and material from a financial viability perspective (as opposed to a purely reputational perspective, for example).

Potential categories of risk include macroeconomic, operational, political and financial. While assessing each of these risks individually helps to identify those with the greatest impact, modelling a number of risks simultaneously is likely to reveal more about the level of financial resilience in the business as it will consider the compounded impact of multiple risks materialising, which is also in line with the primary purpose of a stress test. Such analysis needs to be based on thorough qualitative assessment and supported by statistical analysis. The risk combinations need to reflect severe but plausible scenarios in order to ensure reliable and realistic results.

Figure 2 Stress-testing process

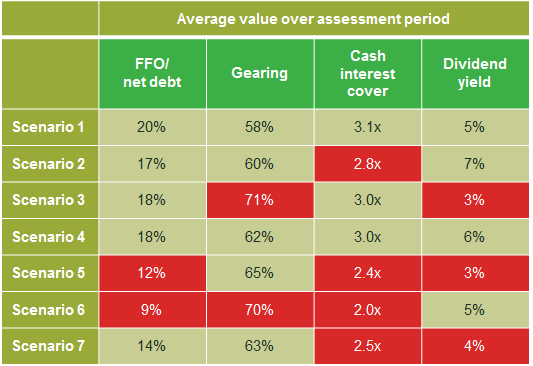

Once the set of selected scenarios is determined, the third stage is the modelling itself. Cash-flow shocks will affect financial statements, which in turn will translate into changes in credit metrics. For example, a customer payment strike would result in higher bad debt costs, reducing available funds from operations, weakening interest cover ratios, and increasing the amount of new debt that the company needs to raise. Consistently low inflation might erode the company’s regulatory asset base (RAB) and result in a higher gearing ratio. However, lower inflation would also mean that the company’s interest payments on index-linked debt would decrease, possibly improving the interest cover ratios—and the overall effect might therefore be muted through a ‘natural hedge’ in the company’s structure. An example of the output from a risk-modelling exercise is shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Stylised output

Source: Oxera analysis.

Finally, water companies have to identify appropriate measures to mitigate the impact of the risks that they have identified. For example, they might need to ask:

- what scope is there for additional CAPEX and OPEX reductions?

- could shareholders contribute via dividend cuts or an equity injection?

- could the company apply for a price control re-opener?

A relevant consideration here is whether the preferred mitigation measures are in line with consumer interests and therefore acceptable to regulators. Difficult questions such as this are part and parcel of the stress-test exercise.

Just a box-ticking exercise?

While the shift in the level of requirements is being led by policymakers and regulators, could the companies themselves benefit from such stress-testing exercises? This could well be the case.

First, the companies are likely to have to go beyond their current risk-modelling practices by considering wider impact risks, their various combinations, and provisional mitigation measures. This will provide better information about the resilience of the business and may therefore help to raise the standard of risk management within the firm and provide better-quality inputs to long-term treasury planning.

Second, a detailed financial viability assessment can help to convey key messages to company boards, non-executive directors and audit committees. In other words, the difficult questions that a company will have to answer as part of this analysis can actually improve communication between different levels of business management and other stakeholders.

Finally, public assurance that the company considers its long-term financial resilience seriously and has put in place mitigation measures that are compatible with consumer interests can help to foster consumer confidence and improve the company’s reputation. In addition, robust modelling in this area will increase the quality of the company’s business plan, which is an important consideration during a price review.

1 The regulator responsible for promoting high-quality corporate governance and reporting in order to foster investments in the UK and the Republic of Ireland.

2 Financial Reporting Council (2014), ‘The UK Corporate Governance Code’, September, p. 17.

3 Financial Reporting Council (2016), ‘Annual review of corporate reporting 2015/2016’, October, p. 32.

4 Bank of England (2015), ‘The Bank of England’s approach to stress testing the UK banking system’, October.

5 Ofwat (2014), ‘Board leadership, transparency and governance – principles’, January.

6 Ofwat (2014), ‘Board leadership, transparency and governance – holding company principles’, April.

7 Ofwat (2016), ‘Consultation on how companies demonstrate long-term financial resilience’, January.

8 Ofwat (2016), ‘Consultation on how companies demonstrate long-term financial resilience’, January, p. 4.

9 For example, see the licence conditions for Thames Water and electricity distribution networks: Department of the Environment (2015), ‘Instrument of Appointment by the Secretary of State for the Environment of Thames Water Utilities Limited as a water and sewerage undertaker under the Water Act 1989’, June; and Ofgem (2016), ‘Electricity Act 1989. Standard conditions of the Electricity Distribution Licence’, 10 August.

10 An international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system.

11 Financial Reporting Council (2016), ‘Annual review of corporate reporting 2015/2016’, October, p. 32.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More