Gender, competition policy and the grossly undervalued domestic product (GUDP)

Does modern economics value the work of men more than women, and if so, what can be done about it? The traditional approach to economics prioritises fee-earning work rather than unpaid housework and caring duties, which are undertaken largely by women. Sarah Long, Partner, Euclid Law, discusses the benefits of incorporating this unpaid contribution into competition law internationally.

This article is adapted from a speech given at the Chillin’ Competition Conference, 20 November 2018, Brussels. The views expressed are solely those of the author and were made in a personal capacity.

The 2018 Adam Smith Lecture was, for the first time, given by a woman. Sandi Toksvig, best known as a British–Danish comedian and author, but who also co-founded the Women’s Equality Party in the UK, told the story of her friend Barbara:1

Barbara is or rather she was a senior nurse. She has two children, aged five and six, and her husband Dan is in the engineering corps of the army. Dan is currently on active duty, and he goes away all the time. Meanwhile Barbara looks after the children and runs the house. Dan’s mother is disabled and lives in a granny flat so Barbara has to get her up in the morning and put her to bed in the evening. Barbara is also a Parent Governor at the school, she volunteers at a clinic and she runs a group for new mums who are having problems breast feeding. She would like to go back to work but the childcare costs make it unviable. She lives in England which has the most expensive childcare in the world. She is officially classified by the UK government as ‘economically inactive’. Zero contribution to the world.

Toksvig calls Barbara’s contribution the Grossly Undervalued Domestic Product (GUDP).

Adam Smith is, of course, known as the founder of modern economics. His most famous work, The Wealth of Nations (1776),2 is considered to be the bedrock of reformed economic thinking. In it, he states: ‘It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we can expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.’ But, as Swedish author, Katrine Marçal, writes in her book, every night his dinner was served by his mother, with whom Adam Smith lived until she died.3 As Toksvig states, it was therefore thanks to Adam Smith’s mother, to her invisible hand, to her GUDP, that he was free to write his great works.4

Much of the noise around gender equality tends to focus on the workplace: ensuring equal pay, female quotas on boards, and trying to ‘have it all’. But for every Sheryl Sandberg, Nicola Horlick and Helena Morrissey (top executives in business and finance), there are millions of women around the world all contributing to this black market of domestic work for absolutely nothing.

So what, if anything, can competition policy do about it? The OECD has been considering how greater gender awareness could be introduced into competition policy,5 and held a round-table discussion6 on the topic of gender and competition policy at the November 2018 Global Forum on Competition. The OECD background paper contains some excellent insight, including on how GUDP could be defined.7

Defining GUDP, substitute services and the double dividend

GUDP is effectively unpaid work. The key factor in defining unpaid work, and distinguishing it from leisure activities, is that a third person could be paid for undertaking such work. So that means activities relating to housework such as food and cleaning services, and activities relating to care services for children, the elderly and the ill. On average, women surveyed in 26 OECD countries and three emerging economies do almost twice as many hours of unpaid work per day as men.8 Solving the problem of GUDP would rely on ‘substitute services’—i.e. paying a third person to do the unpaid activity and releasing women to work in the formal labour market.

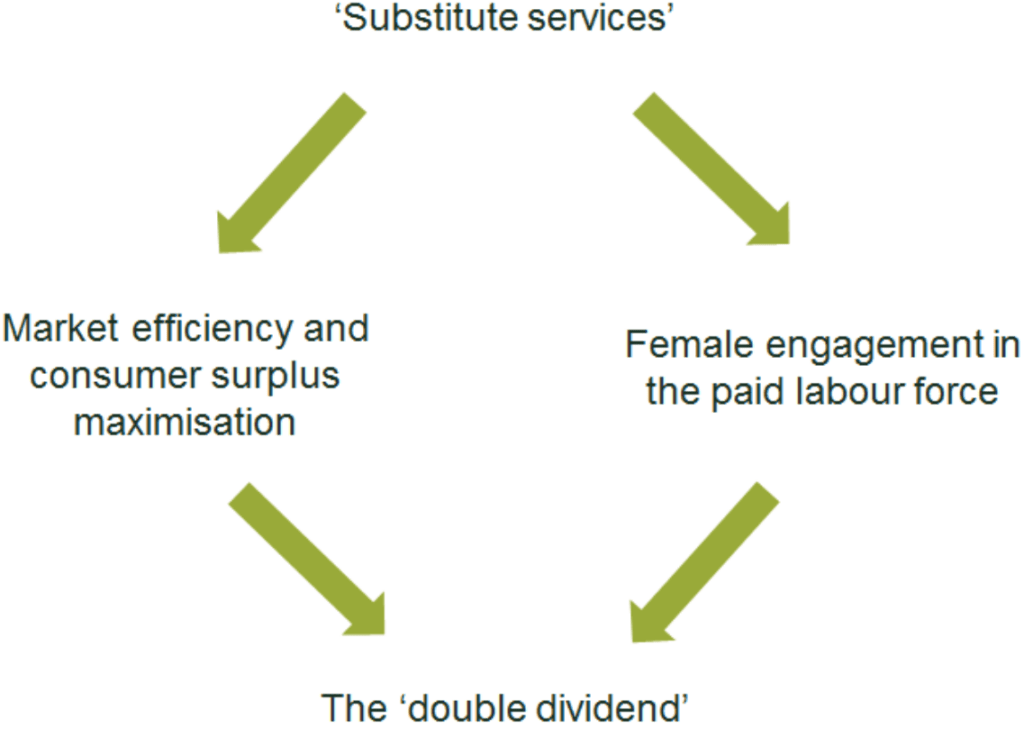

And this is where competition authorities come in. Because if competition authorities were to prioritise those markets in which women supply the biggest share of unpaid work, this could have the potential to reduce the problem of undervaluation. The OECD explains that promoting competition in a sector that provides substitute services to those services that women provide in the household could achieve two goals: first, market efficiency and consumer surplus maximisation; and second; boosting of female engagement in the paid labour force. The OECD calls this the ‘double dividend’ (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 The double dividend

The double dividend in practice

There are already some interesting examples of the double dividend in practice. The current growth plan of Japanese Prime Minister, Shinzo Abe, has recognised the need to introduce reforms in order to increase the involvement of women in the labour market. However, in Japan childcare is done mostly by women and there is not enough of it, meaning huge waiting lists for childcare and the inability of women to go back to work. In 2014, the Japanese Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) carried out a market study on the childcare sector in Japan, looking to identify the reasons for the lack of supply.9 The JFTC concluded that facilitating competition would be critical to improving both the quality and availability of these services.

Although the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has yet to look at childcare, it has carried out a market study on residential and nursing care homes for the elderly.10 This ties in with the CMA’s focus on vulnerable consumers, which is a core target area under its 2018/19 Annual Plan.11 The CMA found that greater support was needed for those requiring care, and that additional public funding was needed. However, interestingly, the market study does not explicitly take gender into account. And this is despite, as the OECD points out, the significant role of women as both informal care providers and recipients of care due to their higher life expectancy than men.

Going beyond substitute services, the concept of ‘gender mainstreaming’ (assessing how public policy affects genders differently) can also have valuable outcomes. A good example of this can be found in Sweden. In 2015, following the introduction of gender mainstreaming in infrastructure policy, Stockholm modified its snow-clearing priorities to ensure the clearing of pedestrian routes first.12 This was because evidence had found that women’s use of transport differs from that of men—generally, women combine income-generating activities with caring and unpaid activities in the household, resulting in more local and repeated trips and greater use of public transport, cycling and walking. Other examples of gender mainstreaming include altering lighting and bus transport management to ensure that women can travel safely at night.

Putting gender on the agenda

These examples are enlightening. To return to the example of Barbara, substitute services would make a big difference to her life. And of course one of the primary reasons she cannot go back to work is the cost of childcare. Without this being a plea to the CMA to open an investigation into the prohibitive cost of childcare in the UK (an issue very close to my own heart), there is a serious message here. Putting gender on the agenda of prioritisation principles for competition authorities could have significant benefits for both consumer and total welfare.

According to the World Economic Forum Global Gender Gap Report 2017, at the present rate of progress we may not achieve gender equality for 217 years.13 But we will never reach gender equality until each and every one of us, male and female, does something about it. We must therefore recognise the concept of GUDP, talk about it and consider how competition policy can tackle the inequity of those whose unpaid work goes unvalued by modern economics.

1 See Toksvig, S. (2018), ‘Extracts from Adam Smith Lecture’, 16 March.

2 Smith, A. (1776), An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations.

3 Marçal, K. (2016), Who Cooked Adam’s Smith’s Dinner?, Pegasus Books.

4 Toksvig, S. (2018), ‘The gender pay gap isn’t the half of it: our economy runs on women’s unpaid work’, The Guardian, 9 April.

5 Pike, C. (2018), ‘What’s gender got to do with competition policy?’, oecdonthelevel, 2 March.

6 OECD (2018), ‘Gender and competition’, 29 November.

7 Santacreu-Vasut, E. and Pike, C. (2018), ‘Global Forum on Competition: Competition Policy and Gender’, 29 November.

8 OECD (2018), ‘Gender and competition’, 29 November, para. 21.

9 Japan Fair Trade Commission (2014), ‘Study Report on Childcare Sector’, press release, 25 June.

10 See Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Care homes market study’, 22 March.

11 See Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘CMA puts vulnerable consumers at the heart of its annual plan’, news story, 29 March.

12 Gee, O. (2013), ‘Sweden warms to “gender equal” snow ploughing’, The Local, 11 December.

13 World Economic Forum (2017), ‘The Global Gender Gap Report 2017’.

Download

Related

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More