Green signal for the Northern rail franchise: assessing mergers in passenger rail

The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has completed its first in-depth (Phase 2) rail franchise case in over ten years—one of the largest it has ever dealt with. The investigation into the award of the Northern rail franchise to Arriva examined more than 1,000 local overlaps between Arriva’s bus services and Northern’s rail services, and over 150 rail–rail overlaps. Ultimately remedies were required on only three overlaps. What are the main insights?

Oxera advised Arriva throughout the CMA’s investigation of the Northern franchise acquisition. For the CMA’s decision, see Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Arriva Rail North and the Northern rail franchise’, A report on the completed acquisition by Arriva Rail North Limited of the Northern rail franchise, 2 November.

The operation of passenger rail services in Great Britain is based on the government awarding franchises to private train operating companies for a limited period of time, following a competitive tendering process. Arriva was awarded the Northern rail franchise—which covers passenger rail services in northern England—in December 2015 for a period of nine years.1 The turnover of the Northern franchise was £568m in the year ending 3 January 2015.2 Arriva operates other rail franchises in Great Britain, including CrossCountry and Arriva Trains Wales, and an open-access operator, Grand Central.3 It also operates bus services around the country, including in the area covered by the Northern franchise.

In January 2016, the CMA launched a merger investigation into the UK Department for Transport’s award of the Northern franchise to Arriva.4 The regulator was concerned that the award would eliminate the competition that may have previously existed between Arriva’s bus and Northern’s rail services (bus–rail overlaps), and also between Arriva’s other rail and Northern’s rail services (rail–rail overlaps).

For example, consider a situation where Arriva bus and Northern rail services are the only ways to travel between two towns (i.e. the two services ‘overlap’). Previously, if Arriva increased the prices of its bus services, customers could switch to Northern rail services (which were formerly operated by Abellio/Serco). This competition could be expected to constrain Arriva’s ability to increase its prices or reduce the quality offered on its bus services (as to do so could result in an unprofitable loss of customers to Northern rail).

With Arriva now also operating the Northern franchise, the CMA was concerned that the competitive constraint between the two services could disappear, such that Arriva would find it profitable to raise the prices of its bus services and/or its unregulated rail fares, or reduce quality. This concern is effectively the same as the concerns arising in mergers, which is why the franchise award was analysed in a similar way to merger investigations.

Following a ten-month investigation into the impact of the contract award on competition, the CMA concluded that the award raised competition concerns on only three ‘flows’ on which Northern overlaps with Arriva’s rail services, and no concerns where it overlaps with Arriva’s bus services.5

This case raises a number of economic issues that may have implications for future rail franchise cases.

What is an ‘overlap’?

In order to determine whether there are likely to be competition concerns, it is important to first define the areas in which Arriva’s bus and Northern’s rail services overlap, and where Arriva’s rail services overlap with those of Northern.

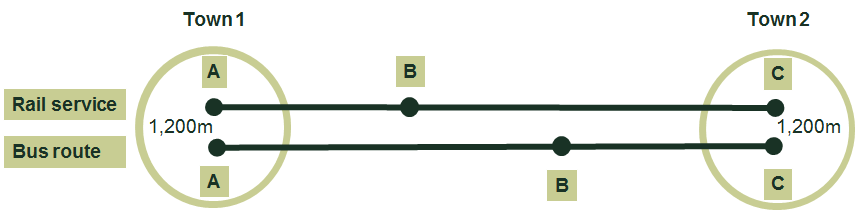

A bus or rail route may have multiple stops. Travel between any two stops/stations is called a flow, and a route therefore consists of multiple flows. Figure 1 illustrates three separate flows on each of the bus and rail services: A–B; B–C; and A–C. Because any combination of two stops on a route is a flow, the number of flows on a route increases exponentially with the number of stops: a route with two stops has one flow in each direction; a route with four stops has six; and a route with 30 stops (which is not unusual) has 435.

Figure 1 Identifying the overlaps

A relevant factor is how close bus stops and rail stations need to be to one another in order for the two services to be considered an overlap. In this case, as in previous cases, the CMA adopted a 1,200m catchment area for identifying overlaps between bus and rail services.6

For instance, as illustrated in Figure 1, Arriva may run a bus route between towns 1 and 2 that stops at three stops (A, B, and C). Northern may also have a rail service that runs between the two stations (A and C) in towns 1 and 2 via a third station (B). However, only bus stop A and rail station A, and bus stop C and rail station C, are within 1,200m of one another. The flows between A and B and B and C do not count as overlaps, as bus stop B and rail station B are not within 1,200m of one another. Therefore, travel between A and C is the relevant flow to consider when examining the competitive effects of the merger.

On this basis, the CMA identified 1,068 overlaps between Arriva’s bus services and Northern’s rail services, and 167 overlaps between Arriva’s rail services and Northern’s rail services—making it one of the largest rail franchise cases ever to be dealt with by the CMA or its predecessors.

Filtering analysis

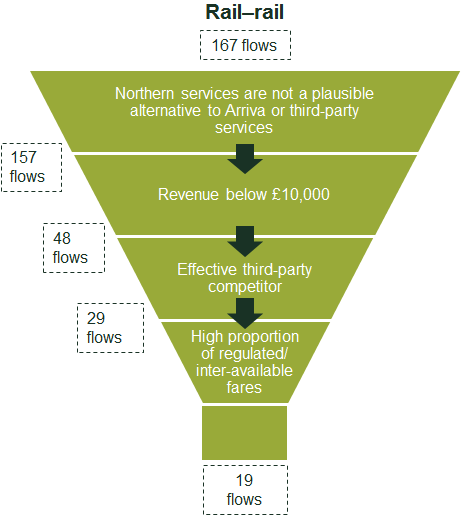

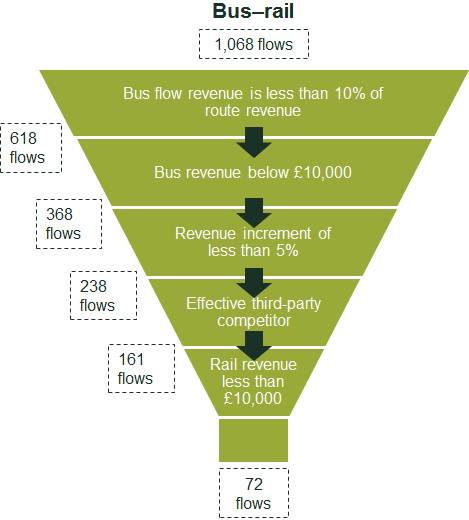

Given the large number of overlaps in this case, it was not possible to consider in detail the effect of the merger on competition for each one. It was therefore necessary to prioritise the overlaps for analysis and focus on those that were considered most likely to lead to a substantial lessening of competition (SLC).

Based on discussions with the CMA, a series of filters was adopted in order to exclude overlaps where Arriva was unlikely to have incentives to raise fares or reduce service quality, as illustrated by the questions below.

- Does a bus flow that overlaps with Northern rail services account for a significant proportion of bus route revenue? Operators are unlikely to have incentives to increase fares and/or reduce service quality if the overlap flows account for only a small proportion of route revenue, as changes to a flow may have negative consequences for other flows or even the whole route. The CMA excluded from any further analysis bus flows where the revenue of all the overlapping flow(s) accounted for less than 10% of the overall bus route revenue.

- Is there significant revenue on the flow? If Northern, other Arriva rail operators (for rail–rail overlaps) and/or the bus service (for bus–rail overlaps) have low revenue, which indicates that not many passengers are carried on the service, Arriva might not have incentives to change fares or service quality. This is due in part to the potential impact that a change on one flow could have on the rest of the route, as described above, but it could also be due to the administrative costs and uncertainty associated with such a change. The CMA excluded flows from further analysis where the revenue of Northern or other Arriva operators for rail–rail overlaps, or Arriva bus or Northern for bus–rail overlaps, was less than £10,000.7 This is equivalent to (on average) fewer than 15 passengers per day on the bus flows, and fewer than five passengers per day on the rail–rail overlaps.

- Do rail and bus services actually compete with one another? If the revenues of the bus and rail services are very different, this might suggest that they are not good substitutes from a passenger perspective, because a significant majority of passengers are not choosing to travel via the option where revenues are low.8 Similarly, if the merger does not materially change Arriva’s share of bus and rail services on overlapping bus–rail flows, then competition issues are less likely to arise because there is no material change to the structure of the market. The CMA excluded bus–rail overlaps where the increment to Arriva’s revenue on that flow from the merger was 5% or less.

- Are there effective competitors on the flow? If there are third-party operators with a significant share of passenger revenue on the overlapping flow, Arriva may not have an incentive to increase fares or reduce service quality. This is because if it were to increase the price, passengers might divert to the alternative operator(s) and Arriva’s strategy might ultimately be unprofitable. For rail–rail overlaps, the CMA excluded from further analysis flows where third-party rail operators had a combined revenue share of at least 50% on that flow. For bus–rail overlaps, the CMA excluded flows where the largest third-party bus operator on the flow operated at least half as many bus services as Arriva on the flow at peak times.

- Is there existing or potential price competition between rail services? Inter-available rail tickets allow passengers to use the services of any rail operator. When a high proportion of fares are inter-available, existing price competition between rail operators may be limited (if it exists at all). Similarly, if a high proportion of fares are regulated, there is little (or no) scope for the rail operators to increase prices. The CMA therefore excluded flows where inter-available fares accounted for 100% of revenue, and regulated fares accounted for more than 80% of revenue on a flow.

The process by which the CMA used these filters to reduce the number of flows, and the impact of the filtering process on the number of flows being examined, is set out in Figure 2 for rail–rail and bus–rail overlaps.9

Figure 2 Filtering analysis

The CMA then undertook more detailed analysis of the flows remaining after the filtering process in order to determine whether they were likely to lead to an SLC.

Generalised-cost analysis

A more detailed piece of analysis undertaken to understand whether the services competed pre-merger was generalised-cost analysis.

There may be differences between services of the same mode of transport, or between different modes of transport, that mean that passengers do not consider them good substitutes. For example, there may be differences in terms of fares, journey time, frequency, or number of interchanges. One way to capture these features is to convert them into monetary equivalents and combine them into one metric. These ‘generalised costs’ of different travel options can then be compared.10

If two services have very different generalised costs, it is unlikely that passengers will consider them substitutes, and there is therefore unlikely to be an SLC on these flows. The CMA focused its detailed assessment of overlapping bus–rail flows on cases where the difference in generalised cost was less than 25%.

The generalised-cost analysis is a one-way test: while operators are unlikely to compete if their generalised costs are different, where the generalised costs of two operators are similar, there may still be important differences between them on different elements of the journey that cancel each other out in the generalised-cost analysis. For instance, one operator might provide fast but infrequent services, while another provides slow but frequent services. The CMA therefore also considered such overlaps in further detail.

Is there a profit incentive to raise prices?

The CMA’s concern was that, post-merger, Arriva would have an incentive to divert passengers from its bus services to Northern rail services—for example, by degrading service quality or increasing bus fares. This is because some lost profits from bus passengers switching away would be recaptured if those passengers diverted to the rail services that Arriva controlled as a result of the merger. However, it is important to take account of any changes in costs for bus and rail as a result of passengers switching between the two, and the fact that some passengers might switch to other modes altogether (such as car) in response to the rise in price or degradation of the bus services. Profit-incentive modelling is an established tool for assessing this and has been used by the CMA’s predecessors in previous rail franchise cases.

Arriva and Oxera commissioned a survey to estimate the proportion of bus passengers who would divert from bus to rail in response to a 10% price rise. When the results of the survey were combined with cost information, our analysis showed that Arriva had a limited incentive, if any, to divert passengers from its bus services to Northern rail services. On none of the flows assessed was it estimated that the benefit to Arriva of increasing bus fares or reducing frequency amounted to more than £300.

Even where Arriva would have some theoretical profit incentive on this basis, the potential gains were not sufficient to incentivise it to raise fares, given the associated uncertainty, potential effects on the rest of the route and wider network, and costs involved. This analysis was a key factor in the CMA’s final conclusion that there were no SLC concerns on any of the bus–rail overlaps.

Concluding remarks

The Northern franchise is currently the largest in Great Britain (in terms of number of services operated).11 While the case started with 1,068 bus–rail overlaps and 167 rail–rail overlaps, after a detailed and thorough investigation, the CMA ultimately had very few concerns in relation to the potential reduction in competition as a result of the merger. It found an SLC on three rail flows—Leeds to Sheffield, Wakefield to Sheffield, and Chester to Manchester—and determined that there should be behavioural remedies in the form of price caps for unregulated fares on these flows. The CMA did not find SLCs on any of the bus–rail overlaps, largely because it considered Arriva to have insufficient incentives to increase bus fares on the overlapping flows (as such strategies were unlikely to be profitable). However, the outcome of the CMA’s analysis is specific to the facts of this case, and should not necessarily be taken as a signal that the CMA will not raise concerns on bus–rail overlaps in the future.

Given that this was the first in-depth (Phase 2) rail franchise merger investigation in over ten years, and that a number of franchises will be re-let over the next few years—including South Western, West Midlands and West Coast during 2017, and four more in 2018—this decision provides useful insight into how the CMA may approach future cases.

1 The franchise was awarded to Arriva Rail North Ltd (ARN), a subsidiary of Arriva plc. Arriva began operating the franchise on 1 April 2016.

2 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Arriva Rail North and the Northern rail franchise’, A report on the completed acquisition by Arriva Rail North Limited of the Northern rail franchise, 2 November, para. 18.

3 An open-access operator is a train operating company that operates commercial services without a franchise agreement.

4 The award of a rail franchise constitutes an acquisition of an enterprise under section 66(3) of the Railways Act 1993.

5 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘CMA looks to cap fares on three rail routes’, Competition – press release, 2 November, accessed 22 November 2016.

6 This is a less relevant question for identifying overlapping rail journeys, since the rail stations at either end of the flow are usually the same for both rail services.

7 This was referred to as a ‘de minimis’ threshold. For bus–rail overlaps, this threshold was applied in tandem with a condition that flows could pass the filter only if the cumulative revenue share was below 10%—the ‘de minimis plus’ filter.

8 This assumes that all options for travel on the flow are well established and revenue shares are relatively stable. It would not hold for flows that have recently started and/or are growing rapidly.

9 In some cases, other evidence (such as internal documents) led the CMA to bring back filtered flows for further analysis.

10 This method is often used in transport modelling and appraisal. See Department for Transport (2005), Tag Unit 3.1.2, June.

11 Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Arriva could face in-depth investigation over Northern Rail franchise’, Competition – press release, 12 May.

Download

Related

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More

Cost–benefit analyses for public policy

Cost–benefit analyses (CBA) are commonly applied to public infrastructure projects where there is a degree of certainty about the physical output of the project and the consequent societal benefits. CBA can also be applied to proposed policy and regulatory changes, but there is less clarity about the outcomes and the… Read More