How are Italian consumers reacting to COVID-19?

On 31 January 2020, the first two cases of COVID-19 were registered in Italy. Over the following weeks, the virus spread throughout all Italian regions, and by the second week of March, Italy was under lockdown.1

In a period of crisis, consumers quickly change their behaviour as they attempt to adapt to the unfolding situation. Using recent data on consumer trends, we share our insights on how Italian consumers have been behaving in these uncertain times.

How are Italian consumers reacting to the outbreak of COVID-19?

As highlighted in a previous Today’s Agenda note, with the spread of COVID-19 around the globe, many news articles have shared stories of consumers stockpiling basic goods, despite manufacturers and retailers reiterating that there is no problem with supply.2

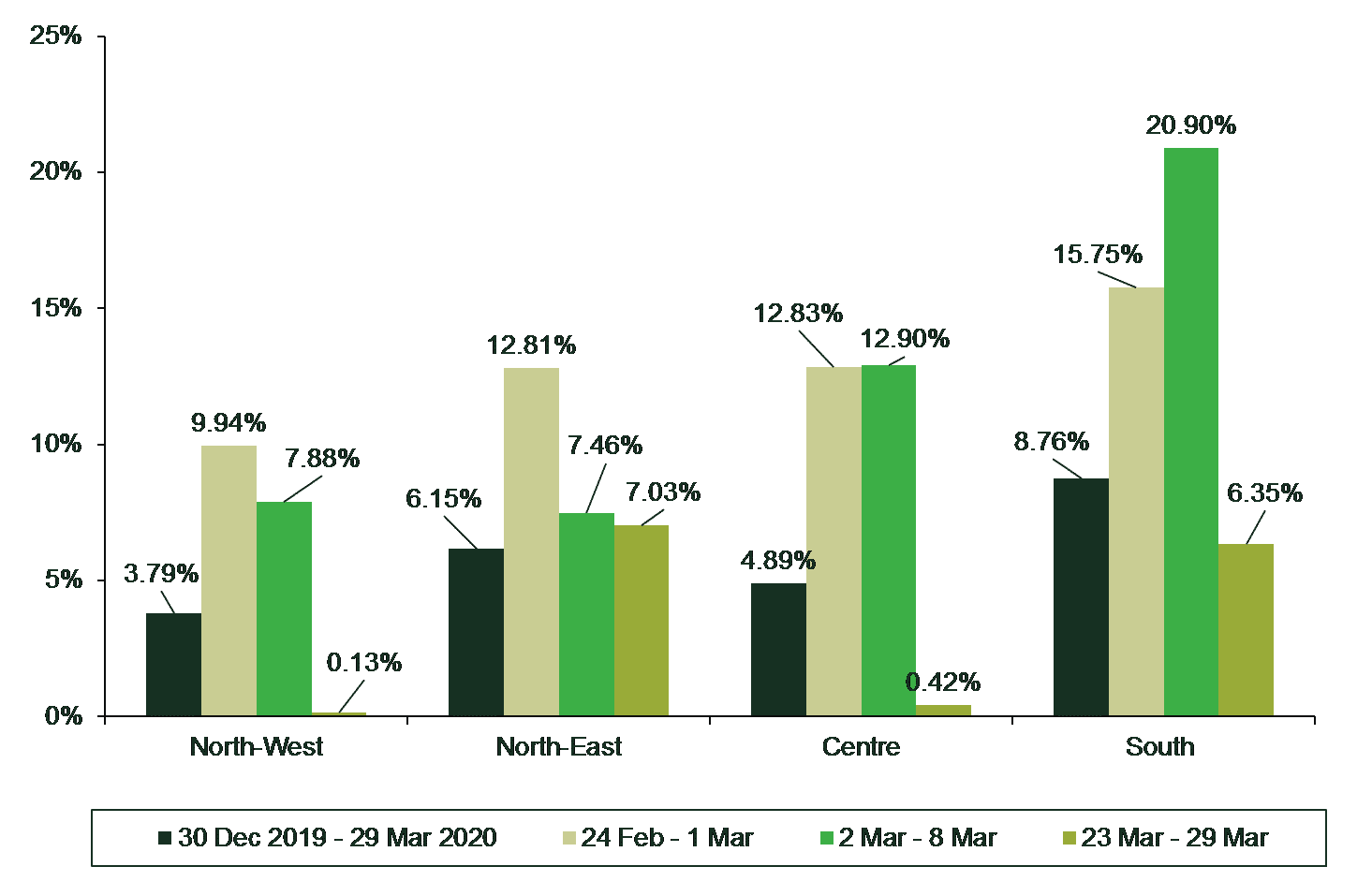

Recent data can shed light on the extent of the stockpiling phenomenon in Italy since the start of the COVID-19 outbreak. Figure 1 below shows that, between 24 February and 1 March, the sales value of large food retailers in Italy increased significantly relative to the same period in 2019. Interestingly, the highest increase was registered in the South of Italy, despite the spread of the virus being focused in other areas at the time.

Figure 1 also points out that panic buying in Italy seems to have been limited to ‘momentum’—i.e. a limited period of time. Starting from the first week of March, a lower or constant increase in the sales value of large food retailers was observable in the North and Centre, respectively. A notable exception is the South of Italy, where the peak occurred during the second week of March. This difference could be attributed to the lagged spread of the virus in the southern regions. Regardless of the delay, the last week of March confirms the decreasing trend in the gross revenues of large retailers in the whole country.

Figure 1 Percentage change in sales value in large retail trade, by macro-area

Source: Statista (2020), ‘Impact of coronavirus (COVID-19) on sales values in large retail trade in Italy between February and March 2020, by macro-region’, 7 April; Frojo, M. (2020), ‘Gdo, le vendite su trend più “normali”’, La Rebubblica.

Possible explanations for the panic buying trend shown in Figure 1 may be found in behavioural economics. The notion of availability bias refers to the tendency of people to overestimate the likelihood of events that they can recall more easily (such as through vivid, well-publicised, or recent information).3 It can result in consumers not assessing the level of risk appropriately, leading to an under- or overestimation of such risk—in this case, shortages of supply. Similarly, herd behaviour, which may be caused by both rational and irrational factors, may lead people to follow what others are doing instead of using their own information to make independent decisions.4 Media representations of risks are likely to influence (and possibly reinforce) such biases.

However, once consumers have experienced the event (in this case, the existence of sufficient capacity and inventory in the supply chain), they may be expected to re-adjust their behaviour accordingly. This might explain the lower increase in the sales value of food retailers in more recent weeks.

How are Italian consumers reacting to the containment measures?

In addition to the panic buying that the spread of the virus may have triggered, consumer behaviour may have been affected by the strict containment measures adopted by the government.5 In particular, we envisage two main consequences of the containment measures: (i) a reduction in the ability of consumers to shop around; and (ii) a shift in demand to e-commerce.

First, we consider that restrictions on individual movement have prevented consumers from shopping around. As a result, Italian consumers have witnessed a decrease in choice when purchasing both essential and non-essential goods. Potentially, the lack of alternatives when shopping could lead to a reduction in the bargaining power of consumers and thus a loosening of competition in the short term. However, this would require careful analysis, given that any increase in prices could also be due to other factors, such as cost shocks.

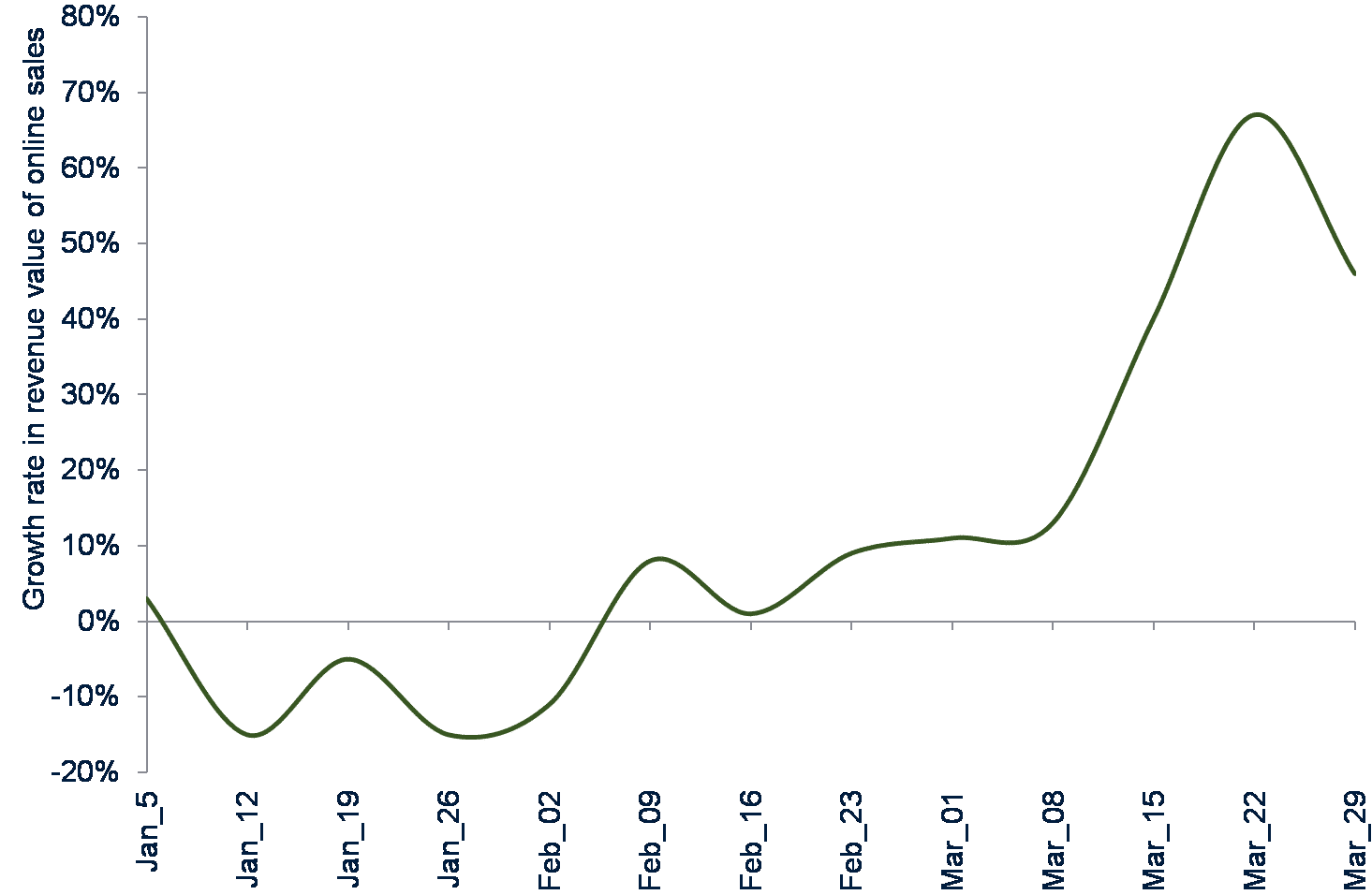

In addition, since current restrictions preclude or limit consumers from buying in physical shops other than supermarkets and pharmacies, we would expect a shift to e-commerce. Indeed, Figure 2 below shows a sharp increase in online retail sales in Italy at the end of February, with a peak in the first weeks of March during the lockdown. However, in the last week of March, online retail sales—although still high—suffered a marked reduction. This could be due to online platforms experiencing delays in their logistics and transport networks (which may also be due to ensuring the health and safety of employees) and IT systems6 (with some choosing to deliver only essential goods).7

Figure 2 Growth rate in online retail sales in Italy in 2020 with respect to the same period in 2019, 5 January–29 March

Source: Emarsys and GoodData (2020), ‘COVID-19 commerce insight’.

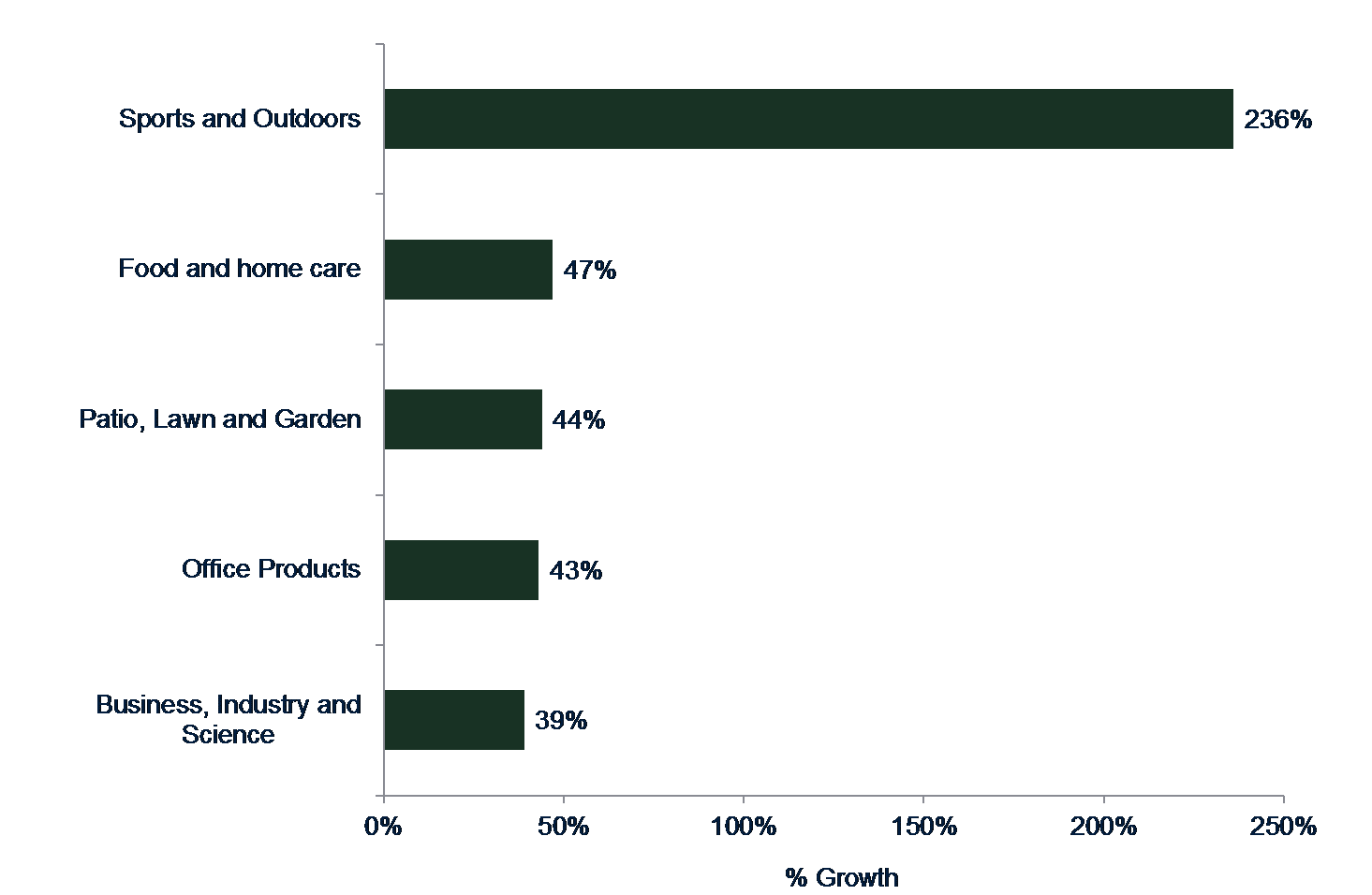

Figure 3 below shows that products relating to sports, food and homecare, home gardening, office and business have been particularly popular among e-shoppers. Conversely, fashion retail platforms seem to be experiencing a decrease in sales.8 These patterns are likely to be linked to a shift in consumers’ preferences towards products that they can use during the lockdown and the need for workers and businesses to organise themselves for smart working from home. However, other factors, such as the aforementioned availability bias and/or a decrease in available income, might also influence e-commerce trends. Even though unemployment statistics during the current COVID-19 crisis are not yet available, the number of people who applied for social assistance programmes adopted by the government is significant, which might suggest a decrease in disposable income.

Figure 3 Top five categories in e-commerce in Italy

Source: MacDonald, Z. (2020), ‘Analysis: Top Selling Products Amid the Coronavirus Crisis – How Demand Is Shifting’, Sellics, 24 March.

As people adapt their behaviour to the lockdown, and more firms turn to e-commerce in order to adapt to the new business environment (including restaurants, book-shops, local butchers and markets), the increasing trend in online sales may reduce the impact of the containment measures on the options available to consumers.

Concluding thoughts

In Italy, recent data shows that panic buying seems to have been limited to a momentum. However, media representations of risks are likely to influence people’s biases. Although the trend is decreasing, the proportion of inaccurate information on COVID-19 is still fairly high in Italy.9 It will be interesting to follow developments in the quality of news on COVID-19 in the coming weeks and its potential impact on consumer behaviour and panic buying. Are there going to be ‘several momentums’—i.e. new instances of panic buying in the future?

As current restrictions limit people’s ability to buy goods in physical shops, consumers may have less choice in the short run—although the increase in online shopping may limit this impact. However, for competition to be unaffected, there would need to be an overlap in what people can buy online and what they can buy in physical shops. Moreover, it remains to be seen whether the increase in e-commerce that we have seen in recent weeks will be affected by external factors such as a lower disposable income of consumers and/or challenges to the logistics systems of online retailers.

1 The timeline leading to the final lockdown included the following main events: on 21 February, a few small towns hit by the virus outbreak in the North were placed under quarantine; on 4 March, all schools and universities were closed; on 8 March, several northern provinces were placed under lockdown; on 9 March, the lockdown was extended nationwide; on 11 March, all restaurants and bars were closed; on 21 March, all non-essential production processes were halted.

2 For Italy, for example, see La Repubblica (2020), ‘Coronavirus, code ai supermercati: “Non serve, tutto sotto controllo”’, 10 March.

3 Kahneman, D. (2011), Thinking, Fast And Slow, Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

4 See Asch, S.E. (1952), Social Psychology, Prentice-Hall; and Posner, R.A. (2013), ‘Behavioral Finance Before Kahneman’, Loyola University Chicago Law Journal, 44, pp. 1341–1348.

5 These measures include the closure of all business activities apart from those deemed essential (e.g. pharmacies, food retailers and banks). For the legislation and measures adopted in Italy to tackle the COVID-19 crisis, see Italian government (2020), ‘Coronavirus, la normativa vigente’, 1 April; and Ministero della Salute (2020), ‘Governo decide chiusura attività produttive non essenziali o strategiche. Aperti alimentari, farmacie, negozi di generi di prima necessità e i servizi essenziali’, 23 March.

6 For example, Amazon.com Inc.’s night-time website traffic in Italy quadrupled from an average of 5Gbps per second before the virus outbreak to about 20Gbps during the third week of March—see Lepido, D., Thomas, S. and Drozdiak, N. (2020), ‘Internet Traffic is Surging But The Pipes Aren’t Bursting Yet’, Bloomberg, 20 March.

7 See Ruffilli, B. (2020), ‘Coronavirus, rivoluzione Amazon, consegna solo di beni di prima necessità’, La Stampa, 21 March; and Redazione Food (2020), ‘Coronaviruso, è boom di spesa online con consegna a domicilio’, Il sole 24 ore, 11 March.

8 SimilarWeb (2020), ‘Mapping the Italian Coronavirus impact, Investor solutions 2020’, White Paper, March. Specifically, sales on fashion retail platforms decreased by 15% in the first week of March relative to the first week of January.

9 According to the Italian communications authority (AGCOM), between 20 January and 22 March approximately 6% of online news on COVID-19 in Italy could be considered fake news. This proportion decreased from a peak of 7.3% in the last week of January to 4.8% in the third week of March. See AGCOM (2020), ‘Osservatorio sulla disinformazione online: speciale coronavirus’.

Download

Contact

Please get in touch at [email protected]

Contributors

Related

Download

Related

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

The National Infrastructure Commission (NIC) has published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED31 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure that the distribution network is strategically reinforced in preparation… Read More

Leveraged buyouts: a smart strategy or a risky gamble?

The second episode in the Top of the Agenda series on private equity demystifies leveraged buyouts (LBOs); a widely used yet controversial private equity strategy. While LBOs can offer the potential for substantial returns by using debt to finance acquisitions, they also come with significant risks such as excessive debt… Read More