Interminable: who can read T&Cs?

Many products form a contract between a firm and a customer, the details of which are specified in the terms and conditions (T&Cs). But do customers always understand what they are agreeing to? With the help of a mathematical formula, we find that the reading age and time requirement of most T&Cs are comparable to reading ten articles in the Financial Times—which raises questions about inclusivity and accessibility.

The location, complexity and length of T&Cs can discourage customers from reading them,1 meaning that they may not fully understand what they are buying. Companies may also deliberately hide exploitative terms in their T&Cs if they know that customers do not typically read them.

In the UK, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) is using the new Consumer Duty (‘the Duty’) to improve consumers’ understanding of financial products.2 As a result of the Duty, firms will be required to do the following.

- Make it easy for customers to understand the products that they are purchasing.

- Do not hide key information in lengthy T&Cs.

- Do not exploit customers’ behavioural biases or vulnerabilities.

- Monitor and review the consumer outcomes.

How are firms currently doing at fulfilling these expectations? We used data science to find out. We looked at the steps required to find the T&Cs. Then, we assessed the ease of reading the T&Cs. Finally, we measured the current market status of 11 insurance providers.3

Where are the T&Cs?

We visited the websites of 11 life insurance products. Figure 1 below lays out where on the consumer journey we found the T&Cs.

Figure 1 Journey to find the T&Cs of life insurance products

Source: Oxera

While the sample size was small, the findings make for interesting reading. Only one provider puts the T&Cs up front. For the bulk of the providers, a customer must click on ‘get a quote’ before accessing the T&Cs. Two providers require a buyer to fill in their personal information first. Lastly, one provider allows access to the full T&Cs only after the insurance is bought. All providers include contact details in the T&Cs in case of questions. Some also make a summary of the full T&Cs available.

We also reviewed eight non-life insurance product websites. Figure 2 below lays out where we found their T&Cs.

Figure 2 Journey to find the T&Cs of non-life insurance products

Source: Oxera.

No provider puts the T&Cs up front. The majority require some personal information to be filled in before the buyer is provided with the T&Cs.

Once you have found the T&Cs, how easy are they to read?

How easy is it to read the T&Cs?

We used formulas to assess the time required to read the T&Cs and how easy they were to read, using the steps below.

- Convert the T&Cs into a text file using optical character recognition (OCR).

- Clean the text file using Regular Expressions (regex) techniques.

- Split the text into characters, syllables, words and sentences. We used the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) library developed for Python by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania.4

- Estimate the number of syllables for each of the words using an algorithm.5

We could then answer two questions. First, how long does it take to read the T&Cs? Second, how easy are they to read?

How long does it take to read the T&Cs?

We calculated a reading time by taking the total number of words and dividing it by the silent reading rate for adults in English for non-fiction (about 238 words per minute).6 Figure 3 below shows the result. Only five unique T&Cs were found in the sample of 11, as several brokers were re-selling the same insurance product.

Figure 3 Reading time of T&Cs of life insurance products and their summaries

Source: Oxera.

The full T&Cs of a life insurance product would usually take 23–43 minutes to read. Summaries take 10–20 minutes. By way of comparison, on average an article in The Sun newspaper takes 1.4 minutes, and an article in the Financial Times takes 3.2 minutes to read. Thus, reading the full T&Cs for an insurance product is equivalent to reading 23 articles from The Sun or ten articles from the Financial Times.

Figure 4 shows the results for non-life insurance products. It shows that the T&Cs for non-life insurance products take even longer to read. For some of these products summaries are not available, so we compared full T&Cs only.

Figure 4 Reading time of T&Cs of non-life insurance products

Source: Oxera.

How easy are the T&Cs to read?

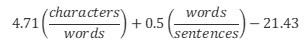

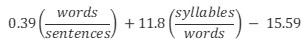

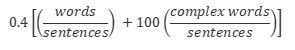

We selected three standard readability formulas, shown in the box below.7 All three identify the US educational grade level that is required to understand the text.

Where:

- characters is the total number of letters and numbers;

- words is the total number of spaces;

- sentencesis the total number of sentences;

- syllables is the total number of syllables;

- complex words is the total number of words consisting of three or more syllables.

Note: 1 Microsoft Word displays Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level test results for its readability statistics.

Source: Oxera.

Results from the formulas in the box were then converted into a reading age using the following steps.

- Take the calculated characters, words, syllables and sentences.

- Estimate the number of syllables for each of the words using an algorithm.8

- Calculate the three formulas in the box above.

- Convert the US educational grade level into age by adding five.

- Rank the indices, and take the value in the middle of the rank.9

Figure 5 shows the results for life insurance products.

Figure 5 Reading age of T&Cs of life insurance products and their summaries

Source: Oxera.

The full T&Cs of a life insurance product require a reading age of 14 to 20. A summary requires a reading age of 13 to 19. To put this into perspective, one in seven adults in the UK have literacy skills at or below those of a 9- to 11-year-old. A survey by the FCA has also found that 17.7m adults in the UK (34%) have poor or low levels of numeracy involving financial concepts.10 The FCA urges companies to take this into account when communicating information relating to a mass-market product.

How do T&Cs compare with what an average person in the UK reads daily? The Sun has one of the highest average daily online audiences, reaching 3m in the UK.11 The average reading age for a Sun article is around 12. All of the T&Cs that we examined are therefore harder to read than articles in The Sun.

So what are these T&Cs actually comparable to? The average reading age for the T&Cs examined is 17, close to those of Financial Times articles. However, Financial Times readers are not a representative sample of the UK population. The Financial Times reports that its average reader has an income of £210,000 and a net worth of $1.8m.12

The findings are similar—if not worse—for non-life insurance T&Cs. Figure 6 shows the result. For the non-life insurance products examined, the reading age ranges from 13 to 22.

Figure 6 Reading age of T&Cs of non-life insurance products and their summaries

Source: Oxera.

Note that the formulas discussed above do not evaluate any figures or tables. To recognise efforts to visualise or summarise the information using figures and tables, firms can test and validate consumers’ understanding using surveys or focus groups.

War and Peace, or war of the words?

Increasingly, insurance products come with T&Cs, many of which can be difficult and time-consuming to read. This could mean that the needs of consumers and what is offered by insurance products are misaligned. In the worst case, T&Cs may not actually be read. Firms could therefore be incentivised to hide harmful features.

In this article we have looked at financial products, but the analysis could be applied more broadly. Streaming services and products in online marketplaces are two examples that could be explored further.

Out of interest, we put this article through Oxera’s algorithm. It takes six minutes to read. The reading age is 14.13

1 For digital products, it is reported that only 9% of Americans always read the privacy policies (a form of T&Cs). Auxier, B., Rainie, L., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Kumar, M. and Turner, E. (2019), ‘Americans’ attitudes and experiences with privacy policies and laws’, Pew Research Center (last accessed 3 August 2022).

2 Financial Conduct Authority (2022), ‘Finalised Guidance: FG22/5 Final non-Handbook Guidance for firms on the Consumer Duty’, July (last accessed 28 July 2022).

3 This sample was selected so as to represent the range and variety of providers in the market, but is not necessarily representative of the whole market or sector.

4 Natural Language Toolkit Documentation (last accessed 28 July 2022). See Bird, S., Klein, E. and Loper, E. (2009), Natural Language Processing with Python, O’Reilly Media Inc.

5 ‘Counting Syllables in the English Language Using Python’, 9 July 2013 (last accessed 28 July 2022). This syllable counter function has a comprehensive set of rules covering a wide range of English words. The author of the blog is unidentified, but Oxera has tested 100 randomly chosen words (ranging from simple to obscurely long words), and manually checked the number of syllables to test the function. We found that the algorithm predicted the number of words with 99% of accuracy. The algorithm and explanations to the logit can be found on the website.

6 Brysbaert, M. (2019), ‘How many words do we read per minute? A review and meta-analysis of reading rate’, Journal of Memory and Language, 109, December.

7 It is easy to compare across metrics with uniform units. These formulas read the whole document. We wanted to erase randomness. We also calculated the SMOG grade (simple measure of gobbledygook), but it is not included here because the SMOG score was incomparably higher than the other three. We took a conservative approach to our figures.

8 ‘Counting Syllables in the English Language Using Python’, 9 July (last accessed 28 July 2022).

9 The correlations among the three metrics, which measure how closely related the indices are to each other, are 0.99, 0.98 and 0.98. Moreover, 79% of the median results pointed to the Flesch–Kincaid result of the three.

10 Financial Conduct Authority (2022), ‘A new Consumer Duty: Feedback to CP21/36 and final rules’, Policy Statement PS22/9, July (last accessed 3 August 2022).

11 Tobitt, C. (2021), ‘Mail Online is biggest UK newspaper brand online, new official industry audience data shows’, PressGazette, 3 September (last accessed 17 October 2022).

12 Financial Times, ‘Specifications & Rates’ (last accessed 31 July 2022).

13 We did not include the footnotes (many of which are references, which are not a prose form). The T&Cs also exclude website links and reference information.

Related

The 2023 annual law on the market and competition: new developments for motorway concessions in Italy

With the 2023 annual law on the market and competition (Legge annuale per il mercato e la concorrenza 2023), the Italian government introduced several innovations across various sectors, including motorway concessions. Specifically, as regards the latter, the provisions reflect the objectives of greater transparency and competition when awarding motorway concessions,… Read More

Switching tracks: the regulatory implications of Great British Railways—part 2

In this two-part series, we delve into the regulatory implications of rail reform. This reform will bring significant changes to the industry’s structure, including the nationalisation of private passenger train operations and the creation of Great British Railways (GBR)—a vertically integrated body that will manage both track and operations for… Read More