Mobile network-sharing agreements: opportunity or threat?

Mobile network-sharing agreements (NSAs) can support investment by relieving capital constraints, lowering the unit costs of expanding networks, and generating network cost savings that reduce both the scale of the investment and operating costs. However, concerns have been expressed about the anticompetitive effects of such cooperation between competitors. Given the importance of examining NSAs case by case, how can one assess their potential anticompetitive effects, and analyse and verify their benefits?

As data demands increase, and mobile network operators (MNOs) seek to remain relevant and competitive by ensuring that they can offer the latest technology (such as 5G), the operators are faced with needing to upgrade and expand their networks. As a result, they are confronted with increased capital and operating expenditure (CAPEX and OPEX) requirements, in an environment where retail revenues per user have declined before stabilising at a lower level in recent years.1 As MNOs have explored new ways in which the costs of investment can be shared, without further consolidation in the market through mergers, they have come to see NSAs as increasingly attractive.

However, as NSAs constitute an agreement between competitors, MNOs need to ensure that they comply with national and EU competition law, which prohibits certain agreements that restrict competition.2 There is currently no certainty on the circumstances under which NSAs will avoid unwelcome scrutiny from competition authorities (and the introduction of safe harbours is unlikely). While the Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (BEREC) has provided some high-level guidance on where competition concerns may be greatest, NSAs are likely to continue to be assessed case by case.3

A detailed understanding of the mechanisms through which NSAs can lead to harms and benefits is therefore needed, supported by a clear framework for how to assess the likely outcomes. This will become increasingly relevant for facilitating potential NSAs that will help to unlock the significant and costly investments in 5G mobile networks that are required to meet EU policy targets, including 5G coverage for all populated areas by 2030.4

A threat to competition?

Guidance from BEREC, and insights from recent investigations by the European Commission into NSAs in Italy and the Czech Republic,5 imply that competition concerns associated with NSAs typically relate to the scope for increased coordination and information-sharing among participants, as well as negative impacts on network competition through reductions in the operators’ incentives to invest and their ability to compete at the network level. The theory is that, where a first-mover advantage is removed (given that any benefits from network upgrades may also be obtained by the other sharing party or parties), the incentives and ability to invest and innovate, or differentiate networks, may be reduced.

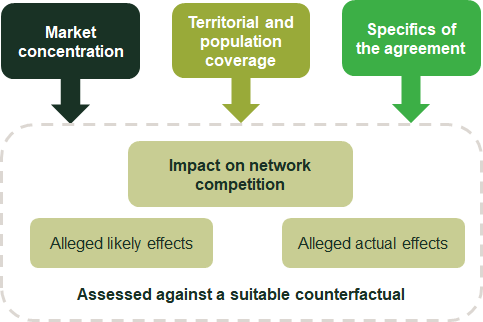

However, the degree to which these issues are of concern will depend on a detailed assessment of market dynamics and the scope of the agreement. Three main features are of particular importance in the eyes of competition authorities when assessing the effects of an NSA relative to a counterfactual of no NSA, or a pared-down version. These are set out in Figure 1 and described below.

Figure 1 Assessing the impact of NSAs on competition

Market concentration

As with mergers, and other cases where theories of harm relate to both coordinated effects and unilateral effects (a loss of direct head-to-head competition, reduced ability to differentiate, higher prices, lower quality), the impact of an NSA on network competition could be deemed more concerning in concentrated markets.

However, as always, the devil is in the detail—and it is vital to look beyond measures of concentration to assess the strength of competitive constraints on the sharing parties. For example, in a four-player market, an NSA among three relatively small players in the market may be less likely to result in competition concerns than one among three parties with relatively high market shares. This is because the sharing parties may still face strong competition from the fourth party. Even if the sharing parties have significant shares, the non-sharing party may still be able to exert a sufficiently strong competitive constraint or act as an external destabilising factor to any coordination.

Among the parties to the NSA, there can also remain scope for differentiation at the service level that could avoid concerns of reduced competition. For example, even with a shared network, operators can differentiate on price and product (for example, in terms of the size of the data package, or special offers), and on the quality of service through different core networks that typically fall outside the NSA. Furthermore, the link between physical networks and the ability to differentiate among services to end-users in order to compete in the retail (and wholesale) markets is likely to become even weaker following developments enabled by new technologies. As explained in the box below, new generations of mobile technology will enable greater scope for differentiation even over a common network infrastructure.

Technology-enabled differentiation

The link between sharing of infrastructure and the ability to differentiate services is likely to be limited in the presence of new technologies. For example, as explored in a previous Agenda article,1 fully developed 5G networks are expected to take advantage of network management features that will provide operators with greater flexibility over their network.

Greater ‘virtualisation’ of networks, which can allow the characteristics of the network to be programmable in a way that abstracts from the underlying hardware, will enable operators to adapt their networks without necessarily having to make changes to the physical infrastructure (which may be shared).

Virtualisation will also play a key role in ‘network slicing’, which will allow operators to separate out different ‘slices’ of their network to meet different requirements and use cases. Operators will be able to define the network characteristics of each slice (including speed, latency and capacity) to meet specific individual requirements.

This could help to preserve service-based competition among sharing parties, as it provides scope for operators to retain greater independent control of their network features and quality even when network infrastructure is shared. Moreover, it could enable MNOs to provide enhanced offerings to mobile virtual network operators (MVNOs) that meet niche requirements with more differentiated service offerings than is currently possible, stimulating greater competition in wholesale mobile markets.

Note: 1 Oxera (2021), ‘Sharing is caring: supporting the roll-out of 5G networks’, July.

Territorial and population coverage

A commonly held view is that NSAs that are focused on rural areas are less of a concern than those in more densely populated areas. Indeed, in the Czech case, the European Commission expressly agreed that ‘Operators sharing networks generally benefits consumers in terms of faster roll out, cost savings and coverage in rural areas’6 [emphasis added]. This is based on the understanding that, in sparsely populated areas, there may not be enough demand to cover the costs of multiple sets of infrastructure, and therefore absent NSAs (or government intervention) the alternative would be simply no mobile coverage.

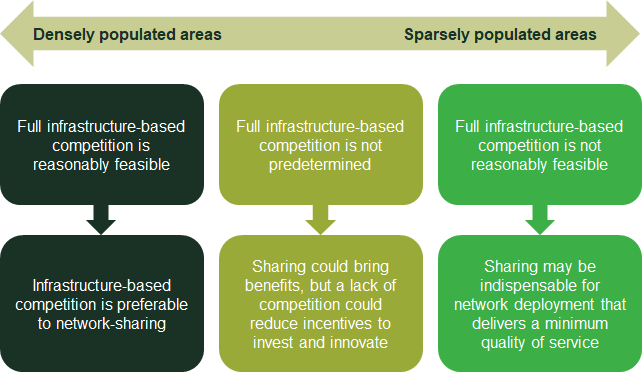

In contrast, due to economies of density, urban areas might be able to support multiple competing infrastructures without an NSA, and a preference for full infrastructure competition tends to prevail among regulators. This urban versus rural distinction is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 The urban versus rural debate

However, this dichotomy is an oversimplification, based on a view of the infrastructure that is already out of date—and will be even more so in a 5G world.

Where the costs of network deployment are significant in urban areas (for example, as a result of requirements for a greater number of sites to meet coverage and capacity requirements), the efficiency benefits of avoiding network duplication (discussed below) will increase and this can play a key role in assessing the balance of effects. Furthermore, if there are some non-replicable site locations in urban areas that MNOs need to access—in order to support unbroken coverage of an area—the absence of some form of NSA at these sites could distort competition by virtue of one operator having access to an ‘essential facility’.

Specifics of the agreement

The specifics of an NSA, such as which assets are shared (is it restricted to ‘passive’ infrastructure such as sites and masts, or does it include some ‘active’ components such as antennae or even radio spectrum?), and the extent and form of any information-sharing, will also be relevant to an assessment of the likely effects on competition.

Passive sharing is generally viewed as having limited adverse impacts on competition—only the physical location of each (shared) site is the same, and operators can differentiate coverage by deploying additional independent sites, and differentiate services by deploying different ‘active’ equipment and different radio spectrum.7

Active sharing agreements, however, involve a ‘deeper’ level of network-sharing, whereby the active equipment that transmits, receives and processes signals is also shared. Concerns raised by competition authorities relate to the extent to which such sharing could have an impact on each operator’s ability to differentiate its network quality and services. However, as discussed above, the link between physical equipment and the ability to differentiate services is not clear-cut where operators continue to maintain separate core networks, can deploy independent sites, or differentiate themselves on other aspects of the service that customers value. The introduction of new technologies and network management tools will further undermine such concerns.

With regard to information-sharing, this should be limited to only that which is necessary for the sharing agreement to function properly. However, competition authorities may raise concerns if there are terms in the agreement relating to sharing information on important strategic decisions that could remove the first-mover advantage gains from, or impede the ability to make, unilateral network improvements.

Assessing the impacts

When assessing the effects of NSAs, there are no bright lines in terms of:

- threshold levels of market concentration, beyond which NSAs become problematic;

- potential anticompetitive effects being unequivocally higher in urban areas than in rural areas;

- whether a particular type of sharing necessarily impedes competition to a material extent.

These theories of harm therefore cannot be presumed. Instead, they need to be assessed carefully, supported by economic evidence, and taking into account the full context of the market, the NSA and the technology in question.

Even in cases where there is a concern that agreements will restrict competition in some way, the cost savings (and their pass-through to consumers) and benefits associated with enhancing consumer choice or service availability must be assessed against any adverse impacts on competition. But what are the likely efficiencies, and how might they be assessed?

The opportunity to generate benefits

That network-sharing agreements can generate efficiencies is well accepted. Indeed, the European Commission has acknowledged that network-sharing can enable cost savings and faster network roll-out, as well as improve coverage.8 Furthermore, the competition law framework can find in favour of agreements that create sufficient benefits to outweigh the (potentially) anticompetitive effects9—so being able to identify and quantify the benefits of NSAs is important.

Network cost savings

NSAs can help to reduce the CAPEX and OPEX associated with deploying and running mobile networks. The magnitude of these savings will depend on a range of factors, including, for example, the type of sharing (e.g. passive or active), technology (3G, 4G, or 5G) and geographic coverage.

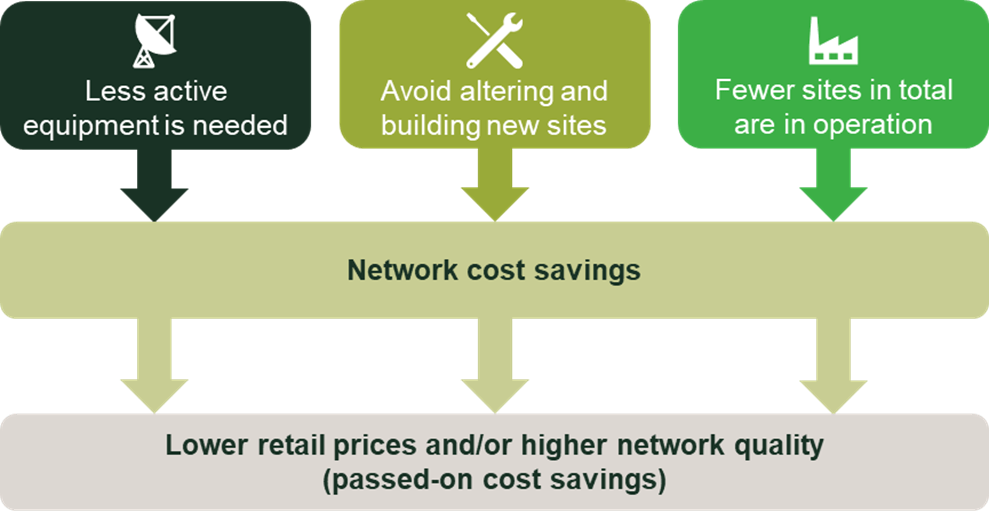

Passive sharing allows operators to share (rather than duplicate) some of the costs associated with deploying the physical infrastructure, such as the costs of masts and towers, and purchasing or renting the space in which to deploy this infrastructure. Fewer sites relative to multiple stand-alone networks can reduce both CAPEX and OPEX. Active sharing, whereby electronic equipment such as transmitters and receivers is also shared, can enable even greater cost savings than passive sharing. Figure 3 shows the source of these additional cost savings, and illustrates how the scope for efficiencies can be even greater for active sharing than those already enabled by passive sharing.

Figure 3 Source of network cost savings from active sharing relative to passive sharing

First, active components will need to be purchased only once across the shared network sites, as opposed to separately by each MNO in the case of passive sharing (or stand-alone networks). This reduces CAPEX.

Second, under passive sharing some sites may not be able to support multiple MNOs’ active equipment, for simple reasons such as space availability or weight restrictions on masts. In such cases, sites would need to be adapted to support multiple sets of equipment, or separate non-shared sites would need to be deployed if this is not sufficient. Active sharing avoids these fixed costs, thereby further lowering CAPEX relative to passive sharing.

Third, as a result of avoiding the need to build non-shared sites, active sharing can reduce the number of sites in operation across the sharing parties. This can reduce the OPEX, such as for maintenance and power, associated with running the network relative to passive sharing.

The box below shows how these cost savings could also be larger for 5G NSAs (particularly in urban areas), such that we may expect to see an increasing number of operators looking to benefit from NSAs to support 5G roll-out.

To the extent that any cost savings enabled by NSAs result in lower marginal (variable) costs, MNOs will also have a greater incentive to pass a proportion of these savings on to consumers through lower prices and/or improved quality,10 and this should be taken into account when assessing the overall impact of NSAs on consumer outcomes.

NSAs lowering the costs of 5G roll-out

Looking forward, NSA-enabled network cost savings—and therefore the benefits of NSAs—could be larger for 5G than for previous generations, particularly in urban areas.

The costs associated with 5G deployment will be significantly higher than for previous generation networks. In particular:

- radio access network infrastructure costs will be significant, given the need to upgrade antennae and to deploy many more cell sites as part of a densification of the network (particularly in urban areas). This is due to the physical propagation characteristics of the higher-frequency radio spectrum required to fully support 5G’s technical capabilities, as explained in detail in a previous Agenda article;1

- backhaul costs will be higher, given the need to cope with significant increases in network traffic and to connect to a larger number of sites;

- energy costs are likely to be high (the GSMA estimates up to 140% higher than for previous generations), due to network upgrades, a larger number of sites, and continued growth in traffic.

Therefore, by reducing network duplication (particularly in urban areas where a large number of sites will be required), 5G NSAs could generate even stronger efficiencies, in terms of cost savings and environmental impacts, than individual network deployments.

The GSMA estimates that network-sharing could potentially deliver savings of up to 40% of the total cost of ownership.

Note: 1 Oxera (2019), ‘Sharing is caring: supporting the roll-out of 5G networks’, Agenda, July.

Source: Oxera, based on GSMA (2019), ‘5G-era Mobile Network Cost Evolution’, 28 August.

Faster network roll-out and greater coverage

Network-sharing can also facilitate faster network roll-out. For example, the sharing parties can pool and coordinate their resources, making roll-out quicker than if they had individually deployed stand-alone networks. NSAs can also help to facilitate greater network coverage by lowering the unit costs of deployment in areas that might otherwise have been too costly to cover.

Therefore, network-sharing can give a larger number of consumers earlier access to improved mobile technologies. Where this brings forward improvements in reliability, access to the Internet, increases in upload and download speeds, and access to a host of new applications and use cases, end-users will stand to benefit much sooner than in a counterfactual of less or no sharing.

Impact assessment techniques can be used to estimate the value of these benefits, alongside other evidence on willingness to pay for improved services, identified through the use of conjoint surveys. These surveys estimate consumer benefits, which can then be scaled up to the affected population in order to present quantitative estimates of the overall benefit to consumers.

On balance…

Assessing the net effect of an NSA will always involve an assessment of the balance between costs (in terms of the impact on competition) and benefits (in terms of the efficiencies generated and how they are shared with end-users). Therefore, when entering into an NSA, having a full and thorough understanding of the possible competition concerns that takes into account the specific market context and nature of the sharing agreement is key.

A robust, economic assessment of the potential benefits, for example in terms of cost savings and faster network roll-out, is integral to understanding the scale of efficiencies that may be generated by any agreement. This can be informative in assessing which type of sharing is best suited to an operator’s business case and identifying important considerations when structuring the agreement. If required, this could also provide valuable evidence demonstrating the benefits of the agreement that could be presented to regulators and/or competition authorities.

1 European Telecommunications Network Operators’ Association (2020), ‘The State of Digital Communications 2020’, 28 January, Figure 2.2.

2 Article 101(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

3 Body of European Regulators for Electronic Communications (2019), ‘BEREC Common Position on Mobile Infrastructure Sharing’, 13 June.

4 European Commission (2021), ‘Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions – 2030 Digital Compass: the European way for the Digital Decade, COM/2021/118 final’, 9 March.

5 European Commission (2020), ‘Mergers: Commission clears acquisition of joint control over INWIT by Telecom Italia and Vodafone, subject to conditions’, 6 March; European Commission (2019), ‘Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to O2 CZ, CETIN and T-Mobile CZ for their network sharing agreement’, 7 August. Oxera advised on both cases.

6 European Commission (2019), ‘Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to O2 CZ, CETIN and T-Mobile CZ for their network sharing agreement’, press release, 7 August.

7 However, in some circumstances, sharing passive infrastructure can give rise to competition concerns. For example, the European Commission’s investigation found concerns that the INWIT joint venture brought together a large number of towers, which could reduce competition in the market for renting space on towers and foreclose telecoms operators from the market. To address this, remedies were imposed, including to make available—on reasonable and non-discriminatory terms—free space on towers to host third-party MNOs’ equipment. See European Commission (2020), ‘Mergers: Commission clears acquisition of joint control over INWIT by Telecom Italia and Vodafone, subject to conditions’, press release, 6 March.

8 European Commission (2019), ‘Antitrust: Commission sends Statement of Objections to O2 CZ, CETIN and T-Mobile CZ for their network sharing agreement’, press release, 7 August.

9 Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

10 Neurohr, B. (2016), ‘A tractable cost pass-through benchmark’, Economics Bulletin, 36:3, pp. 1603–08.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More