Nature: the root of all capital?

Natural capital is relevant to all of us, not just those who are environmentally conscious. An unbalanced focus on financial or economic capital has led countries and companies to focus on policies that deliver short-term financial or economic gains, but at the expense of a longer-term loss in terms of other, non-financial aspects (such as social or human capital). Such an approach is arguably unsustainable.

Natural capital is that part of nature which directly or indirectly brings value to people, and includes ecosystems, species, freshwater, soils, minerals, the air and oceans, as well as natural processes and functions. Natural capital underpins other types of capital, such as human, social, manufactured and financial capital. In combination with other types of capital, natural capital forms part of our wealth; that is, our ability to produce actual or potential goods and services into the future to support our wellbeing.1

Range of approaches

Natural capital is now a priority in policymaking circles. The EU’s Green Deal is an umbrella for many environmental initiatives.2 It ‘aims to protect, conserve and enhance the EU’s natural capital, and protect the health and well-being of citizens from environment-related risks and impacts’, while stating that ‘[a]ll EU actions and policies will have to contribute to the European Green Deal objectives’. The Green Deal goes beyond lofty intentions and states that ‘the Commission will also support businesses and other stakeholders in developing standardised natural capital accounting practices within the EU and internationally’.

Natural capital accounting is an essential part of the renewal of biodiversity. The United Nations has proposed the System of Environmental Economic Accounting—Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA EA). This is an integrated framework for organising information about ecosystems—it was developed to make the contributions of nature to people and the economy more visible, and was adopted by the United Nations Statistical Commission in March 2021.

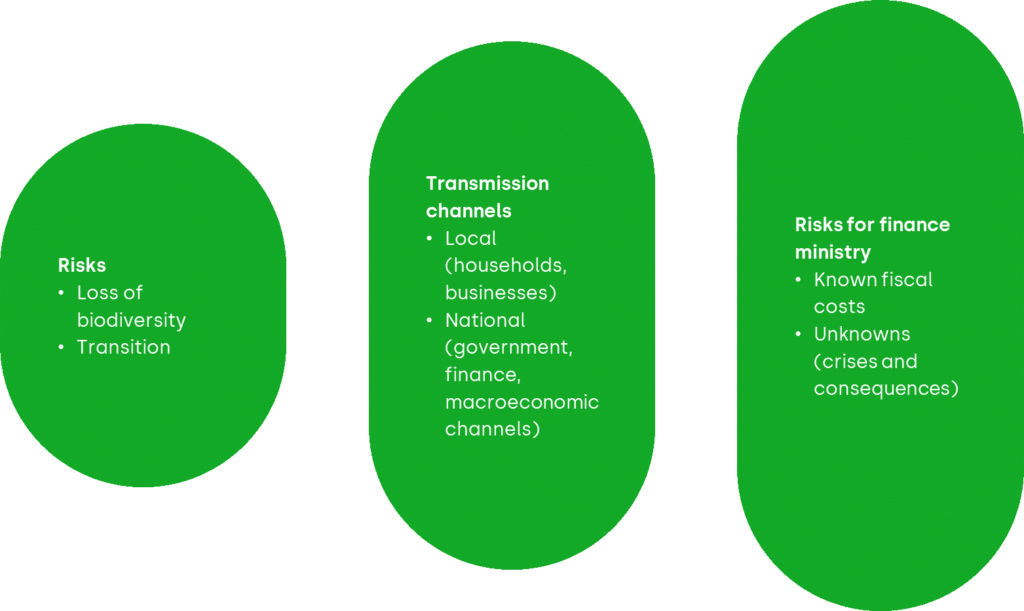

Finance ministers have also identified the loss of biodiversity as a key source of additional national risk. The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action has produced a report on recommended policy actions in response to nature-related risks.3 As shown in Figure 1, these policy actions were informed by a risk analysis, which saw a combination of physical risks (such as ecological shocks and declining agricultural yields) and transition risks in moving to alternative systems. These risks are then manifested through channels such as households, businesses and national-level factors (such as lower tax revenues, increased investment, financial risks and macroeconomic influences). The result is a risk-management agenda for the finance ministry, which also recognises that not all risks will be known in advance.

Figure 1 Nature-related risks

For some ministries, the interest in environmental risk is even more direct. In the UK, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (Defra) has produced a 25-year plan that notes the need to manage natural capital, and states that ‘We will also set gold standards in protecting and growing natural capital – leading the world in using this approach as a tool in decision-making’.4

The private sector also has a role in developing natural capital. One group that seeks to bring stakeholders together is the Capitals Coalitions,5 a global collaboration to transform decision-making—which has produced a Natural Capital Protocol, alongside a Social and Human Capital Protocol. These protocols provide a framework for integrating capital concepts into decision-making and organisational processes, based on a measurement and valuation of the capitals.

Meanwhile, among investors, natural capital is attracting attention on two fronts. For example, the investment manager, Schroders, notes that the depletion of natural capital creates significant, but underestimated, risks to investors in financial capital—and that investment decisions must anticipate these risks.6

However, we note that it is not all gloomy for the private investor. Reversing the decline in natural capital, and increasing biodiversity, will require investments in infrastructure and skills—which represents an opportunity for future investment. In particular, the energy transition requires significant upfront capital expenditure that will benefit equipment suppliers and installers—large and small.

Having touched on public procurement, those who wish to win major contracts in the UK must now make explicit how the proposed solution would contribute to social value.7 This is evaluated against a ‘social model’, one theme of which is ‘fighting climate change’, whose policy outcome is ‘effective stewardship of the environment’. There are award criteria relating to additional environmental benefits and persuading the community to support environmental protection.

Community support can also be seen in willingness-to-pay surveys, which can be used to support investment cases that have an impact on natural capital. This is especially true in the case of public infrastructure investments that have a major impact, which is often negative during construction but potentially positive during operation. The Construction Innovation Hub (an independent research organisation receiving support from government and industry) has produced a specialist tool, the Value Toolkit.8 This allows companies to define a value framework based on their own corporate priorities, and to use this for decision support during the construction and operation of infrastructure. The Toolkit has been endorsed by the UK Treasury, which notes that ‘[i]t could be particularly useful in both development and delivery workshops, to help translate high level economic, environmental, and social objectives into key areas of focus for design and delivery’ (June 2022).9

But what does natural capital involve? Unfortunately, there is little agreement, although the SEEA-EA will lead to a convergence of measurement principles. In the UK, the influential Natural Capital Committee (now wound up, but created as an advisory forum following the 2011 Natural Environment White Paper) opted for a ten-fold categorisation:10 species, ecological communities, soils, freshwaters, land, atmosphere, minerals, sub-soil assets, oceans and coasts, which has an intuitive correspondence to factors that most people associate with natural capital.

A further perspective is provided by the UK’s independent Dasgupta Review on the Economics of Biodiversity,11 which sets out a new framework for how we should account for nature in economics and decision-making. It argues that human demands on nature must be reduced while the ‘supply’ of nature is increased through nature-based solutions and an increase in biodiversity. Furthermore, it states that the limitations of gross domestic product (GDP) must be recognised, with alternatives already being proposed in the form of (for example) China’s Gross Ecosystem Product and New Zealand’s Living Standards Framework.

Common themes

Despite a lack of consensus on the components of natural capital, some common themes are emerging:

- there is a need to recognise stocks and flows of natural capital, with flows either depleting or increasing the level of stocks of capital;

- it is desirable to measure the level of stocks of natural capital to confirm the sustainability of the ecosystem;

- there is a recognition of natural capital as a source of ‘ecosystem services’, which can be combined with other services and the benefits received from the locality or a proposed investment. These ecosystem services could include food, energy or recreational use.

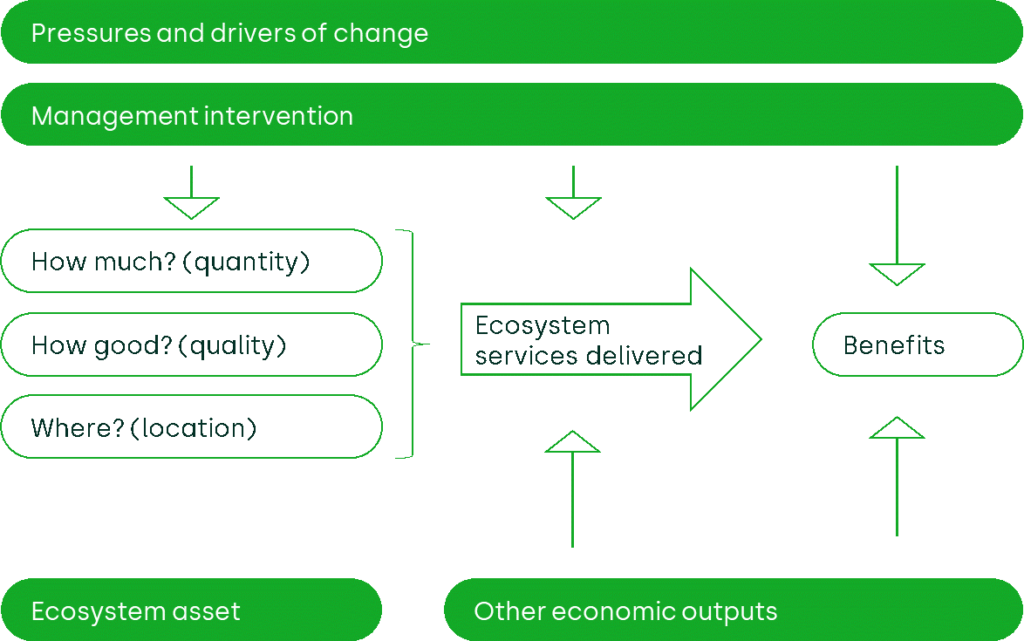

In the UK, these principles have been brought together into the Enabling Natural Capital Approach, summarised in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 Enabling a natural capital approach

The figure shows how pressures, and the need for change, lead to the need for management intervention in the ecosystem. This is seen as a set of assets, which are almost certainly interlinked, with measurable quality and quantity, in specific locations. The ecosystem is combined with other economic inputs to deliver benefits to society, often in a specific place.

The benefits of the Enabling a Natural Capital Approach include:

- reducing the risk of ignoring the value (monetised or not) of the natural environment, by identifying the interdependency of economic activity on the environment—leading to novel policy solutions;

- enabling a spatially aware cost–benefit analysis and risk assessment to identify priorities for investment;

- providing a basis for systematic accounting of natural capital over time.

There will still be a need for formal investment appraisal, although this will be better informed than it is at present.

Investment appraisal

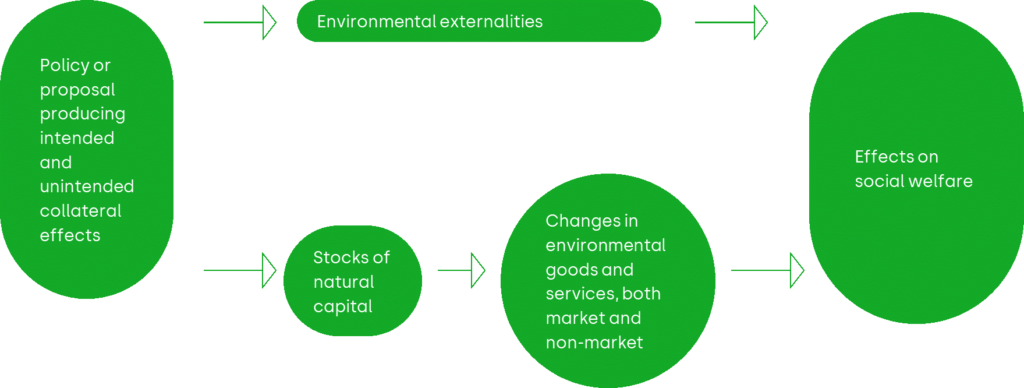

For public investments in the UK, the appraisal should follow the ‘Green Book’ approach12—the UK government’s guide to investment appraisal. Figure 3 is taken from the Green Book and shows the logic flow for undertaking an investment appraisal where natural capital is involved.

Figure 3 Green Book approach

Figure 3 follows a flow of logic that begins with a specific policy or investment, which can lead to environmental externalities (usually negative) and also changes in the level of natural capital. The changes in the levels of stocks of natural capital can then lead to changes in the levels of environmental services available to society (some will have a market value and others will not). Finally, all these prior effects will lead to a change in social welfare, and the benefits of the policy or proposal can be weighed against its costs.

The Green Book begins with a set of screening criteria to determine whether the investment or policy under consideration is likely to affect the following aspects of natural capital, directly or indirectly:13

- the use or management of land, or landscape;

- the atmosphere, including air quality, greenhouse gas emissions, noise levels and tranquillity;

- an inland, coastal or marine water body;

- wildlife and/or wild vegetation, which are indicators of biodiversity;

- the supply of natural raw materials, renewable and non-renewable, or the natural environment from which they are extracted;

- opportunities for recreation in the natural environment, including in urban areas.

If so, the Green Book suggests following a four step process:14

- step 1: identify the environmental context of the proposal (what is proposed, and its location);

- step 2: consider the biological and physical effects on natural assets (how will the proposal work?);

- step 3: consider the social welfare implications of the biophysical effects identified in step 2 (what are the consequences?);

- step 4: consider uncertainties and implementation.

The Green Book stresses that this process is intended to augment, not replace, existing approaches by providing a more comprehensive framework within which to develop and appraise policy. It also suggests additional ways to meet policy goals and enable all options to be assessed.

Once the enhanced perspective provided by the natural capital process has been obtained, there remains the question of how to integrate it into the investment appraisal process. If the UK Green Book is being applied, the first stage is at the strategic outline step—an initial review to move from a longlist of options to a shortlist. The Five Case Model—the UK government’s recommended approach to creating business cases—also provides ample opportunity to include natural capital considerations in the strategic case, and even to use multi-criteria decision analysis15 within the economic case to select the shortlisted options.

There is also the possibility of influencing the next stage, the outline business case, when moving from the shortlist to the preferred option, by including entries in the appraisal summary table that reflect the impact on natural capital.

Measuring the impact of natural capital

The impact of natural capital is to enrich the value framework on which value-for-money decisions are made, and also to provide an accounting framework to track the accumulation (or depletion) of capital over time, to ensure the long-term sustainability of the selected option.

When deciding whether to incorporate natural capital into an appraisal of a project or a policy, the question is whether the project or policy will affect natural capital and biodiversity. If so, how can the damage to natural capital be avoided, especially at the construction stage? This could involve the repurposing of existing assets rather than their replacement.

Other questions relate to how the stocks of natural capital and biodiversity can be increased over the lifetime of a project, and how this increase could be measured.

Lastly, one could look at how the benefits of the changes in natural capital can be maximised, in terms of the effect on social welfare—for example, by improving accessibility. In this way, the net social benefit of a project or policy can be enhanced and it will be moved up the prioritisation ranking for funding, to the benefit of both the project sponsor and the wider public.

1 Definition adapted from Natural Capital Committee (2013), ‘The State of Natural Capital: Towards a framework for measurement and valuation’, April.

2 European Commission (2019), ‘Communication from the Commission: The European Green Deal’, 11 December.

3 Power, S., Dunz, N. and Gavryliuk, O. (2022), ‘An Overview of Nature-Related Risks and Potential Policy Actions for Ministries of Finance: Bending the Curve of Nature Loss’, The Coalition of Finance Ministers for Climate Action, June. Crystallin, M., Moren, P. and Boissinot, J. (2022), ‘Finance Ministries, Central Banks and Supervisors Recognize Nature-Related Risks and Commit to Deepening Their Understanding]’, The Coalition for Finance Ministers for Climate Action, 5 December.

4 Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (2018), ‘A Green Future: Our 25 Year Plan to Improve the Environment’, p. 9.

5 Capitals Coalition website, accessed 27 January 2023.

6 Marshall, J. (2022), ‘Q&A: What is “natural capital” and why should investors care?’, Schroders, 26 October.

7 Government Commercial Function (2020), ‘Guide to using the Social Value Model’, December.

8 Construction Innovation Hub, ‘Value Toolkit’.

9 Construction Innovation Hub, ‘Value Toolkit’.

10 This differs from the eight-fold UK National Ecosystems Assessment (urban, enclosed farmland, mountains, moors and heathland, freshwater, woodland, coastal margins, marine and semi-natural grassland), which the UK Office for National Statistics uses for collecting data on habitat extent and condition.

11 Dasgupta, P. (2021), ‘The Economics of Biodiversity: The Dasgupta Review’, HM Treasury, February.

12 HM Treasury (2022), ‘The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation’.

13 HM Treasury (2022), ‘The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation’, p. 64.

14 HM Treasury (2022), ‘The Green Book: Central Government Guidance on Appraisal and Evaluation’, p. 74.

15 Booth, R. (2021), ‘Investment appraisal in the round: why MCA?’, Agenda, February.

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More