Package deal: why the Airtours criteria are also relevant for understanding cartels

The Airtours criteria set by the EU courts in 2002 play an important role in assessing the risk of (tacit) coordinated effects in merger review. However, since the three criteria—transparency, deterrence, and external stability—reflect fundamental economic theory concerning coordination between competing firms, they are relevant for understanding any form of collusion—including, for instance, in the context of cartel damages litigation.

In its 2014 Damages Directive, the European Commission introduced a legal presumption that cartels cause harm, and it falls upon the defendants to show otherwise.1 This presumption helps claimants in arguing their case in front of courts. However, illegality of conduct does not on its own imply harm, and the Damages Directive indeed notes that the presumption of harm is rebuttable, depending on the facts of the case.

This raises an important question in cartel damages proceedings: exactly when is an economic expectation of harm reasonable?

In this article, we explain that the Airtours criteria established by the EU General Court in 2002 provide a valuable framework for assessing whether an economic expectation of harm is reasonable.2 Although these criteria (transparency, deterrence, and external stability) have been established in the context of an appeal against a merger decision by the Commission, we show how they reflect the fundamental economic theory concerning coordination between competing firms and therefore apply to any form of collusion.

After discussing the fundamental economics of collusion, we explain exactly why the Airtours criteria are a reflection of this theory—and hence why they are relevant for understanding collusion and cartels in general.

The implication of this is that when the evidence in a damages case suggests that one or more of the Airtours criteria are not met, this can be a material issue insofar as an economic expectation of harm is concerned. Robust inference then requires competition practitioners and courts to engage carefully with the available evidence.

The fundamental economics of collusion: solving the prisoner’s dilemma

Economists define collusion as a situation in which competing firms coordinate their behaviour, generally for the purpose of increasing prices.3

As collusive agreements are usually prohibited, any such outcome must be self-enforcing. This means that each firm needs to find it in its best interest to abide by the arrangement, as long as all other firms do. However, self-enforcement of a collusive outcome is not straightforward: in principle, economic incentives typically push firms to compete rather than collude, despite the fact that they could get higher joint profits if they coordinated. This situation equates to the prisoner’s dilemma.

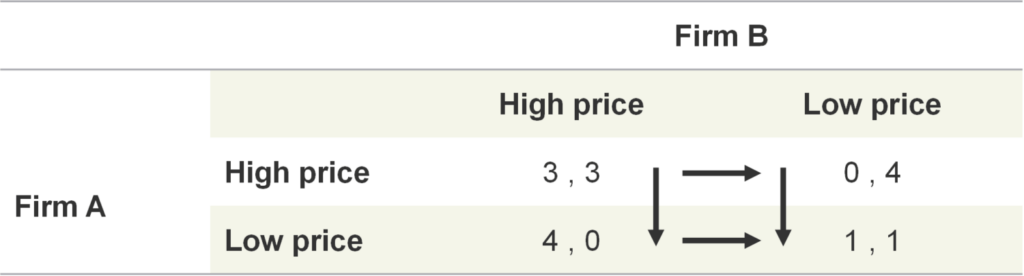

Table 1 provides an illustration of this using a so-called ‘pay-off matrix’. The first entry in each cell in the matrix reflects the pay-off of Firm A and the second entry that of Firm B for each combination of options. This shows that firms can maximise their combined profit by both setting a high price (both receiving 3). However, each firm can always achieve a higher individual profit by setting a low price, irrespective of what the other firm does. This is indicated by the arrows, which reveal that the only possible mutual best response (i.e. equilibrium) is when both firms set low prices (i.e. compete).

Table 1 Competition as a prisoner’s dilemma

Source: Oxera.

To ‘solve’ this prisoner’s dilemma and break the economic forces that lead firms to compete, an aspiring cartel faces two key challenges.

Coordination challenge

First, competing firms need to coordinate on a common understanding of what the appropriate terms of coordination are.

In our simple illustration, this is straightforward (both set a ‘high’ price); but it can be seen how in many real-world markets (with many different price points and firms that differ in terms of their costs, capacity, product position, and demand expectation), reaching and maintaining a common understanding of what is the best outcome to coordinate on is often no easy feat.

Firms can aim to overcome this coordination challenge by communicating with each other on the exact terms of the coordination or by dividing up markets among themselves. However, any communication to that effect is likely to be unlawful and must be carefully hidden to avoid detection and likely prosecution.

Stability challenge

Second, firms need to ensure cartel stability in the sense that each firm finds it in its best interest to abide by the arrangement, as long as all other firms do.

If the above game is static (i.e. played only once), there is little that firms can do to ensure that an understanding to set high prices is stable. Each firm has an incentive to set low prices instead, and there is nothing that can be done to take away this incentive. However, this may change when firms expect to compete with each other also in future periods and the game becomes dynamic (i.e. is repeated many times).

There is a consensus in modern economics theory that, in order to make a collusive outcome stable, firms would need to rely on a history-dependent reward–punishment strategy.4 This is where firms reward others when those other firms stick to the collusive outcome, but credibly threaten to punish them when they depart from it. It is this threat of punishment that enforces the agreement.

One obvious example of such a strategy would be to simply agree to maintain collusion as long as the other firms do (reward), but to set competitive prices permanently once at least one firm deviates from the agreement (punishment).5

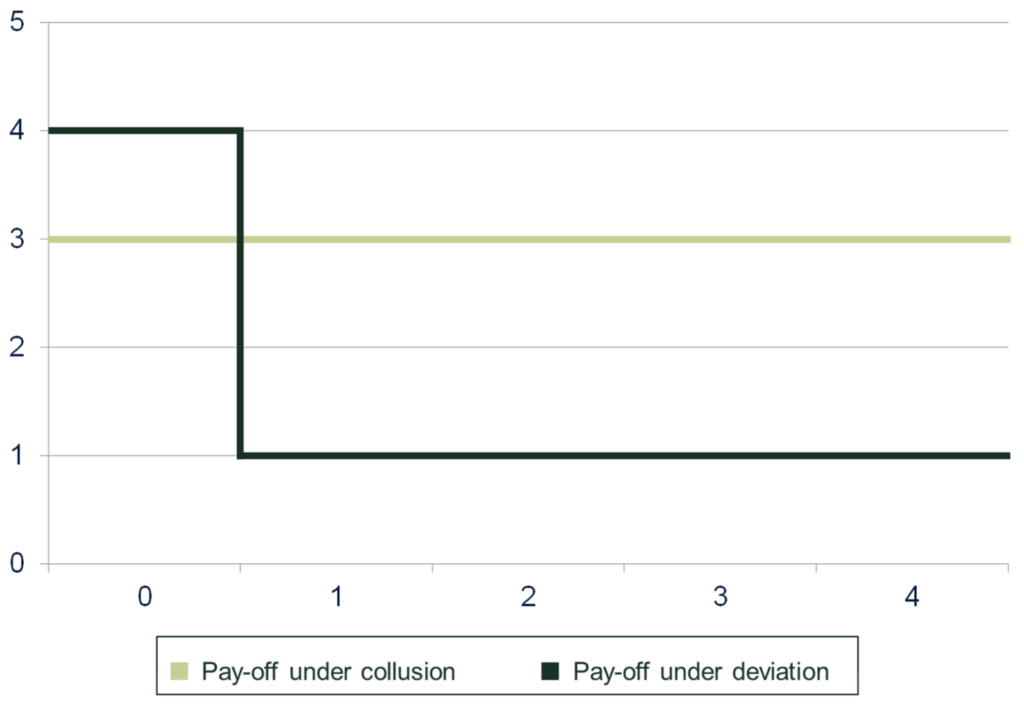

Taking the pay-offs as given in Table 1, such a strategy leads to a trade-off between two options:

- maintaining collusion—receiving a pay-off of 3 in each future period by sticking to the collusive outcome;

- deviating from the collusive agreement—receiving a one-off higher pay-off of 4 today by deviating, but a lower pay-off of 1 for each period thereafter.

Figure 1 illustrates this trade-off. It becomes immediately clear that in this case, the cartel agreement is stable as long as firms are not too impatient (i.e. they place sufficient weight on future pay-offs to be willing to sacrifice some short-term profits in the first period of the game).6

Figure 1 Per-period pay-offs in a reward–punishment strategy

Source: Oxera.

This reward–punishment strategy is the essential mechanism that allows collusion to work.

Note, however, that this economic definition of collusion may not actually be the same as how a lawyer would define unlawful collusive conduct (i.e. a cartel). We turn to this next.

The distinction between economic collusion and unlawful collusive conduct

When economists talk about collusion, they generally have in mind a situation in which competing firms adopt a reward–punishment strategy in order to achieve a ‘supra-competitive’ equilibrium (such as prices above their competitive level). However, such equilibrium analysis does not specify how a particular equilibrium is reached.

This is in contrast to competition law, which focuses instead on conduct in the form of an agreement or ‘concerted practice’.

More specifically, the legal practice of having to consider conduct follows from the fact that collusion occurs somewhere along a spectrum:

- explicit collusion—firms explicitly exchanging assurances that they will pursue the same supra-competitive outcome;

- tacit coordination—firms in a concentrated market all setting supra-competitive conditions purely based on a unilateral recognition of their shared economic interest to do so (also known as ‘conscious parallelism’).7

Both forms of collusion have the capacity to increase prices above competitive levels and harm competition. However, tacit coordination cannot always be challenged under Article 101 TFEU or equivalent laws in other jurisdictions, as it may not always be possible to meet the evidentiary standard required to identify such conduct as an agreement or concerted practice.8 Economic collusion therefore need not be ‘unlawful’ in the sense of infringing Article 101 TFEU.

Similarly, unlawful collusion need not be economic collusion. For instance, a (mutual) expression of collusive intent can be prosecuted on a by-object basis, even if punishment by firms is not feasible and hence a collusive equilibrium cannot be stable.9

There is good reason for investigating cartels on a by-object basis. To take a metaphor used by Advocate General Kokott in the 2009 T-Mobile Netherlands case, ‘a person who drives a vehicle when significantly under the influence of alcohol or drugs is liable to a criminal or administrative penalty, wholly irrespective of whether, in fact, he endangered another road user or was even responsible for an accident’ (emphasis added).10

However, in the context of damages litigation, the question remains: under what conditions can we presume that the unlawful collusive conduct also led to meaningful collusion in the economic sense?

This is where Airtours comes in.

Airtours v Commission (2002)

In 1999, the European Commission concluded that the merger between Airtours and First Choice, two UK operators for packaged holiday tours, would significantly impede competition and decided to block it.11

The concern in most merger cases is that of unilateral effects, where merging parties are expected to act on the incentive to increase their own prices after the merger because they are no longer concerned about the share of customers who would leave to the other firm. In response to such a price increase by the merging parties, other firms active in the market could also increase their own prices, exacerbating consumer harm.12

In this case, however, the concern related not to unilateral effects, but to coordinated effects: the Commission concluded that the merger would create a position of collective dominance in the UK market for short-haul foreign package holidays. Rather than competing, the limited number of firms active in this market may decide to set supra-competitive conditions—either through some form of explicit collusion or purely based on a unilateral recognition of their shared economic interest to do so.

That same year, the parties appealed to the EU Court of First Instance (now the General Court), looking to reverse the Decision. The Court agreed and annulled the Commission Decision, concluding that ‘the Commission prohibited the transaction without having proved to the requisite legal standard that the concentration would give rise to a collective dominant position.’13

In the same judgment, the Court identified three conditions necessary for inferring that a collective dominant position can impede effective competition.14

- Transparency—firms must be able to monitor to a sufficient degree whether the terms of coordination are actually being adhered to.

- Deterrence—firms must be able to deter deviations from the terms of coordination through a credible retaliation mechanisms that can be activated if deviation is observed.

- External stability—it should not be easy for outsiders to destabilise the coordinated outcome, such as through entry by new competitors or countervailing responses by customers.

Even though the Airtours case was one involving a merger, these conditions are a direct reflection of the fundamental economic theory discussed above: without transparency and deterrence, cartel member would always have the ability and incentive to ‘cheat’ on the cartel by undercutting competitors in some way.

As such, the Airtours criteria are relevant when investigating any form of economic collusion.

Airtours: a package deal

Cartels generally cause harm.15 The 2014 Damages Directive therefore provides for the rebuttable legal presumption of harm in cartel damages litigation. At the same time, the fact that cartels are often investigated and challenged on a by-object basis means that the conduct of firms may be sanctioned under Article 101, even without any evidence that the conduct had an effect on prices or other aspects of competition.

In cartel damages proceedings, a key question preceding a case-specific empirical assessment then becomes: exactly when could an economic expectation of harm be reasonably maintained?

One established element to this is the nature of the cartel infringement: hardcore cartels (such as the fixing of final prices or the division of markets) are generally accepted to cause harm, while in other forms of horizontal coordination (such as information exchange) the effects are more ambiguous—even if they infringe on competition law.

However, we have shown in this article that the Airtours criteria provide for an additional framework to help assess the economic validity of maintaining an expectation of harm.

In many cases, demonstrating that the Airtours criteria are met is a straightforward task. However, when the economic and factual evidence in a case indicate that one or more of the Airtours criteria are not met, robust inference of an economic expectation of harm requires competition practitioners and courts to engage carefully with the available evidence.

1 EU Damages Directive 2014/104/EU, recital 47. This presumption does not apply retroactively, but a comparable ‘factual presumption’ may still be relied upon by courts. See, for instance, German Federal Court of Justice (‘FCJ’) Judgments on Case KZR 35/19, 23 September 2020 and Case KZR 19/20, 13 April 2021, which relate to the ongoing litigation following the trucks infringement. Note, however, that in these judgments, the FCJ did conclude that a ‘factual presumption’ does not by itself reverse the burden of proof to the defendants. Instead, the weight ascribed to this presumption has to be analysed on a case-by-case basis, in light of all of the specific facts and evidence available in the case.

2 EU Court of First Instance Decision on Case T-342/99, Airtours v Commission, ECR II-2585 (2002).

3 See, for example, Harrington, J.E. (2017) The Theory of Collusion and Competition Policy, The MIT Press, Chapter 1.

4 While the conceptual ideas behind cartel (in)stability go back at least to George Stigler in the 1960s, the first game-theoretical formalisation of reward–punishment strategies is provided by James Friedman and Dilip Abreu in in the 1970s and 1980s. See Stigler, G.J. (1964), ‘A theory of oligopoly’, Journal of Political Economy, 72:1, pp. 44–61; Friedman, J.W. (1971), ‘A Non-Cooperative Equilibrium for Supergames’, The Review of Economic Studies, 38:1, pp. 1–12; Abreu, D. (1986), ‘Extremal Equilibria of Oligopolistic Supergames’, Journal of Economic Theory, 39, pp. 191–225; Abreu, D. (1988), ‘On the Theory of Infinitely Repeated Games with Discounting’, Econometrica, 56, pp. 383–96. For seminal textbook treatments in this theory of repeated games, see Tirole, J. (1988), The Theory of Industrial Organization, The MIT Press; Vives, X. (1999), Oligopoly Pricing: Old Ideas and New Tools, The MIT Press; Motta, M. (2004), Competition Policy: Theory and Practice, Cambridge University Press. A modern textbook treatment is included in, for instance, Belleflamme, P. and Peitz, M. (2015), Industrial Organization: Markets and Strategies, Cambridge University Press. Valuable case discussions on how firms are able to maintain collusive outcomes in practice are provided by Harrington, J.E. (2006), ‘How do cartels operate?’, Foundations and Trends in Microeconomics, 2:1, pp. 1–105; Levenstein, M.C. and Suslow, V.Y. (2006), ‘What determines cartel success?’, Journal of Economic Literature, 44:1, pp. 43–95; Marshall, R.C. and Marx, L. M. (2012), The Economics of Collusion: Cartels and Bidding Rings, The MIT Press.

5 This strategy is known as a ‘grim-trigger strategy’, because it is very pessimistic in its implications for the firms involved: an apparent deviation is immediately punished with a return to competition and never forgiven. In both theory and practice, more sophisticated strategies involving for instance temporary or more aggressive punishment also exist (see footnote 8).

6 In addition to the relative value placed on future profits, many other factors affect this trade-off between maintaining collusion and deviating from the agreement—and hence whether firms will be able to overcome the cartel stability challenge. For a comprehensive but accessible discussion of these different factors, see in particular Ivaldi, M., Jullien, B., Rey, P., Seabright, P. and Tirole, J. (2003), ‘The Economics of Tacit Collusion’, Final Report for DG Competition, European Commission, March, and Ivaldi, M., Jullien, B., Rey, P., Seabright, P. and Tirole, J. (2007), ‘The Economics of Tacit Collusion: Implications for Merger Control’, in The Political Economy of Antitrust, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

7 Some economists propose a three-way distinction between (i) explicit collusion, (ii) tacit collusion, and (iii) conscious parallelism, where tacit collusion would be described as firms expressing in some way an intention to set supra-competitive conditions (unlike conscious parallelism), but with the implicit understanding that others will do the same, so without any explicit exchange of assurances (unlike explicit collusion). See, for instance, Harrington, J.E. (2017), The Theory of Collusion and Competition Policy, The MIT Press, Chapter 1. Conduct falling under this definition of tacit collusion could be prosecuted, based on the expression of intent. However, considering tacit collusion as possibly prosecutable runs somewhat counter to what is commonly understood as tacit collusion (which aligns more with that of conscious parallelism).

8 In US antitrust law, tacit coordination in terms of conscious parallelism is typically not even prohibited in principle, on the grounds that ‘it is close to impossible to devise a judicially enforceable remedy for “interdependent” pricing’ (Clamp-All Corp. v. Cast Iron Soil Pipe, 851 F.2d, at para. 484, US First Circuit, 1988)—i.e. firms cannot be forced to compete. See also Harrington, J.E. (2017) The Theory of Collusion and Competition Policy, The MIT Press, Chapter 1.

9 Economists are in part at fault for any confusion on the distinction between economic collusion and unlawful collusion. For instance, economists often refer to ‘tacit collusion’ when they are instead considering mechanisms underlying economic collusion in general. This may give the potentially misleading impression that the general theory only applies to cases of tacit coordination. See, for instance, Ivaldi, M., Jullien, B., Rey, P., Seabright, P. and Tirole, J. (2007), ‘The economics of tacit collusion: implications for merger control’, in The Political Economy of Antitrust, Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

10 Advocate General Kokott’s Opinion in Case C‑8/08 T-Mobile Netherlands and others (2009), para. 47.

11 European Commission Decision on Case No IV/M.1524 – Airtours/First Choice (1999), para. 194.

12 Higher prices from oligopoly competition are not the same as collusion. In oligopoly competition, higher prices are the result of firms using their strategic interdependence, even if they interact only once (i.e. the firms cannot achieve cartel stability because they can never retaliate in the case of deviation) and aim to maximise their own profit (i.e. they do not collude by object). Firms can of course also collude in a setting of oligopoly competition, but calling oligopoly competition itself ‘collusion’ is an economic misnomer.

13 EU Court of First Instance Decision on Case T-342/99, Airtours v Commission, ECR II-2585 (2002), para. 294.

14 Ibid., paras. 62–3.

15 See, for instance, our discussion in Oxera (2009), ‘Quantifying antitrust damages: towards non-binding guidelines’, study prepared for the European Commission, section 4.1.

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More