Putting the genie back in the bottle—deposit return schemes on plastics

In March 2018 the UK government announced a plan to introduce a deposit return scheme for plastic, glass and metal drinks containers in England. Aimed at curbing pollution by stimulating recycling, the scheme will be consulted on later this year, and will bring England into line with many other EU countries that already have such schemes. From a traditional and a behavioural economics perspective, what conditions are necessary in order for these schemes to achieve the intended policy objectives?

As the issue of global plastic pollution has gained increasing scrutiny and publicity, support for the introduction of recycling initiatives has grown. According to the European Commission, more than half of EU citizens are convinced that local authorities should provide more and better collection facilities for plastic waste, and over 60% think that consumers should pay an extra charge for single-use plastic goods.1

It has been estimated that, since the 1950s, approximately 8.3bn tonnes of plastic has been produced globally, of which almost 80% has ended up in landfill or the natural environment.2 The environmental cost of plastic pollution in 2015 was estimated at more than $139bn.3

However, substituting plastic can be difficult for both environmental and technical reasons. According to the UK Environment Agency, a cotton tote bag must be used 131 times before it becomes a less environmentally detrimental alternative to HDPE disposable plastic bags, given the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from its manufacture and transportation.4

How do deposit return schemes work?

While the details of existing deposit return schemes vary, the general principles are as follows: when purchasing drinks in plastic containers, consumers are charged a higher price, which includes a deposit of £0.06 to £0.35, depending on the country and type of container. The consumer can then claim the deposit back by recycling the container in a return vending machine. The unclaimed deposits can be distributed to retailers, producers or the scheme operator, depending on the exact details of the scheme.

The operation of such schemes (e.g. container collection, installation and maintenance of the reverse vending machines) itself requires financing. Costs are typically levied on the supply side of the market—i.e. the producer, retailer or importer.5 However, producers and retailers can be expected to pass on at least some of these costs, so in practice consumers may bear some of the scheme costs.

What is the precedent for such schemes?

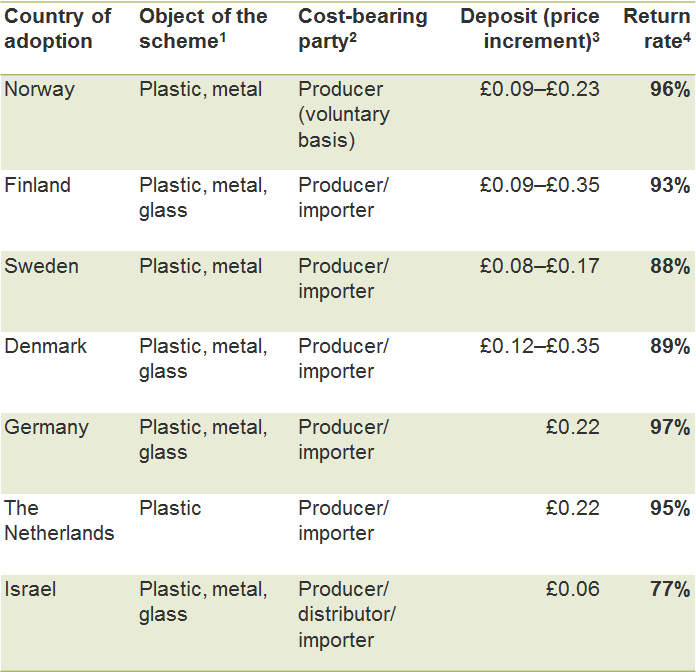

Schemes similar to that proposed in the UK already operate in a range of countries, including Denmark, Germany and Sweden. Key features of these schemes, and their return rates, are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1 Deposit return schemes across countries

Source: Oxera analysis based on CM Consulting and Reloop Platform (2016), ‘Deposit systems for one-way beverage containers: global overview’.

The table shows that the schemes share a similar structure and in most cases result in high return rates, ranging from 77% to 97%. In contrast, only 58% of plastic bottles are currently recycled in the UK.6

How can consumers be incentivised to participate in these schemes? This question is considered below, from the perspectives of both traditional and behavioural economics.

What makes a scheme work?

From a traditional economics perspective, participating in the scheme allows individuals to earn additional income by collecting and returning containers. Therefore, rational economic agents will choose to participate in the scheme, as long as the costs of doing so are below the level of the collected deposits. Indeed, there is evidence of individuals on low income participating in such schemes primarily to obtain additional income.7

However, other evidence shows that financial incentives are not always a driving force behind people’s habits and decisions. For example, even though taxes make up over 80% of the cost of cigarettes in the UK,8 low-income groups appear to have the lowest rates of quitting.9

Behavioural economics offers additional insights into people’s behaviour by examining cognitive and emotional biases.

Cognitive and emotional biases

The endowment effect, whereby people demand much more money to give up an object that they already own than they would be willing to pay to acquire it, is well established in the economics literature. The effect has important implications for the functioning of the proposed scheme.10 The mere fact that the increase in price is labelled as a deposit, as opposed to a levy, can enhance the scheme’s effectiveness. In particular, the prospect of losing a deposit could be a stronger motivator for people to engage in the scheme than the prospect of paying a levy, or even the prospect of receiving some money.11

Another feature of return deposit schemes that encourages engagement is that some may perceive the process as a form of game. ‘Gamification’ is used in many spheres to maintain engagement. There is evidence of gamification successfully encouraging other environmental initiatives. For example, an experiment in which participants managed their energy consumption by competing against their friends and neighbours showed ‘high user acceptance and the potential to engage consumers in participation’.12

Another experiment installed a display in the homes of participants that depicted their avatars on an island. The sea level rose, threatening to sink the island, unless participants engaged in sustainable behaviour. A post-experiment survey showed that 85% of participants developed an increased awareness of environmental ecology.13 Finally, an experiment involving the introduction of an ‘emobin’—a bin that provided immediate positive feedback in the form of emoticons and sounds—showed a threefold increase in recycling.14

The introduction of a scheme may help to change people’s behaviour beyond just the recycling of plastic containers. In a world where environmental awareness is steadily increasing, people may be more willing to participate in environmentally friendly initiatives; however, limited attention spans and the information overload of everyday life mean that many people are also more likely to follow their old habits.

Reverse vending machines near a store can serve as a prompt for consumers to reconsider their habits more broadly. The benefit of a prompt is not so much in educating people, as in giving a reminder at the right time. The simpler the prompt, the more effective it is.

To illustrate this, since 2008 fast-food chains in New York have been obliged to display calorie information on menus, with the aim of encouraging healthier diet choices. The evidence suggests that this measure has failed to achieve its objectives.15 In contrast, there is evidence that simpler, and more visual, traffic-light food-labelling systems are effective in incentivising people to maintain healthier diets.16

A network of reverse vending machines near stores could therefore serve as a prompt to people to change their consumption of plastic over time.

What are the challenges?

In spite of the above factors, there are issues that have the potential to hold the deposit return scheme back from achieving its environmental objectives.

Complexity

Complexity could jeopardise the effectiveness of the scheme in two ways.

From a traditional economics perspective, complexity increases the opportunity costs of participating in the scheme, by which we mean the value of time and effort. All else being equal, higher opportunity costs will be associated with fewer people engaging with the scheme.

From a behavioural economics perspective, even a relatively small amount of additional effort required from participants may affect their decisions. For example, a UK study found that university students purchased fewer sweets and crisps at the cafeteria if they had to pay for them at a separate checkout.17 To the extent that people dislike spending time on understanding how a scheme works, and which items can and cannot be recycled, the more complex the scheme, the lower the level of expected engagement.

The proposed UK scheme would therefore have to be simple to understand and engage with in order to have maximum impact. Similar arguments can be made about scheme convenience.

Costs of the scheme

Another issue is that, no matter how successful a scheme is in changing behaviours, it will not come without a cost. Costs can be broken down into the direct costs of operating the scheme and the wider economic and environmental impact.

While in most schemes consumers do not bear the cost directly, here the operating costs will ultimately be shared between the supply side (producers, importers and retailers) and the demand side (consumers) of the market. The exact distribution of costs depends on a number of factors, such as the degree of consumer engagement and the ability of the supply side to pass the costs on to consumers.

To illustrate, people who do not engage with the scheme will ultimately pay more for it as they will effectively forgo their deposits, which will ultimately be pumped back into the scheme operation. However, consumers who engage with the scheme and do collect their deposit will still contribute some amount towards the operation of the scheme. This contribution will be ‘baked’ into the price of the products in the first instance.

The degree to which the supply side is able to pass on the costs of running the scheme to consumers depends on the market structure (i.e. the number of firms in the market, their market shares, and how intensively they compete). According to standard economics, firms operating under ‘perfect competition’ would pass on all of the scheme cost to consumers, while a monopoly would pass on only 50%.18 In reality, however, the markets involved in the production and distribution of plastic containers are neither perfectly competitive nor monopolistic. In practice, therefore, the degree of pass-on would be expected to fall somewhere between 50% and 100%.

Finally, the distribution of the cost burden within the supply side could also be uneven. To illustrate, simply mandating that all retail stores install reverse vending machines may result in a relatively high burden on smaller chains. Even if the number of machines is proportional to the number of open stores, smaller chains may find it more difficult to finance the machine installation, simply due to their size. This, in turn, could bring unintended competition consequences to the retail food market. At this stage, however, it is unclear which parties are going to share the costs of setting up and running the scheme. It is expected that more clarity will be provided in the consultation later this year.

According to the British Plastics Federation, the UK scheme will cost ‘at least £1bn to set up and a similar [amount] to run each year’.19 At least some of this cost could be expected to be borne by consumers.

In addition to monetary operating costs, the scheme will give rise to an environmental footprint and wider economic effects. To illustrate, the very process of collecting, transporting and recycling plastic will inevitably result in some environmental pollution.

Moreover, the scheme may encourage some local authorities to wind down their own recycling initiatives. This suggests that, to maximise the effectiveness of the scheme and minimise wider costs, it will be important to consider all parts of the recycling chain.

Concluding remarks

Judging from precedent in other, mainly European countries, the deposit return recycling scheme proposed in England has the potential to significantly improve the recycling rates of drinks containers. An economics perspective highlights three areas of focus that will determine the success of the scheme.

- Simplicity and ease of access—regardless of whether people are driven by financial or behavioural motives, simplicity and ease of access of the scheme will be important in maximising the level of engagement. They will allow opportunity costs to be minimised, as well as reduce behavioural barriers that would otherwise deter participation.

- Efficiency of scheme operations—no matter how successful the scheme is in increasing return rates, it will still incur operating costs. Minimising these will be crucial to the efficiency of the scheme.

- The wider effects and the big picture—the scheme will generate its own environmental and economic impacts, which could be both positive and negative. The very process of transporting and recycling plastics results in emissions. At the same time, the presence of reverse vending machines in stores can serve as a prompt that can help people to reconsider their consumption of plastic more generally

1 European Commission (2017), ‘Special Eurobarometer. Attitude of European citizens towards the environment’, p. 20.

2 Geyer R., Jambeck, J.R. and Law, K.L. (2017), ‘Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made’, Science Advances, 3:7.

3 Trucost (2016), ‘Plastics and sustainability: A valuation of environmental benefits, costs and opportunities for continuous improvement’, July, p. 7.

4 HDPE: high-density polyethylene. See Environment Agency (2011), ‘Life cycle assessment of supermarket carrier bags: A review of the bags available in 2006’, p. 7.

5 CM Consulting and Reloop Platform (2016), ‘Deposit systems for one-way beverage containers: global overview’.

6 Harrabin, R. (2018), ‘Drinks Bottles and Can Deposit Return Scheme Proposed’, BBC News, 28 March.

7 Whittle, H. (2012), ‘Berlin’s poor collect bottles to make ends meet’, Spiegel Online, 23 March.

8 Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association, ‘Taxation’.

9 ASH (2016), ‘Ash briefing: Health inequalities and smoking’, p. 7.

10 Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L. and Thaler, R.H. (1991), ‘Anomalies: The Endowment Effect, Loss Aversion, and Status Quo Bias’, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5:1, pp. 193–206.

11 Low, D. (2012), ‘Behavioural economics and policy design: Examples from Singapore’, World Scientific Publishing Company, p. 77.

12 Gnauk, B., Dannecker, L. and Hahmann, M. (2012), ‘Leveraging gamification in demand dispatch systems’, in Proceedings of the 2012 Joint EDBT/ICDT Workshops, presented at EDBT-ICDT 12. ACM, Berlin, Germany, pp. 103–10.

13 Liu, Y., Alexandrova, T. and Nakajima, T. (2011), ‘Gamifying intelligent environments’, in Proceedings of the 2011 International ACM Workshop on Ubiquitous Meta User Interfaces, presented at Ubi-MUI’11, ACM, pp. 7–12.

14 Berengueres, J., Alsuwairi, F., Zaki, N. and Ng, T. (2013), ‘Gamification of a recycling bin with emoticons’, in H. Kuzuoka, V. Evers, M. Imai and J. Forlizzi (eds), Proceedings of the 8th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, presented at HRI 2013, IEEE, New York, pp. 83–84.

15 Cantor, J., Torres, A., Abrams, C. and Elbel, B. (2015), ‘Five years later: Awareness of New York City’s calorie labels declined, with no changes in calories purchased’, Health Affairs, pp. 1893–900.

16 See, for example, Levy, D.E., Riis, J., Sonnenberg, L.M., Barraclough, S.J. and Thorndike, A.N. (2012), ‘Food Choices of Minority and Low-income Employees: A Cafeteria Intervention’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 43:3, pp. 240–8.

17 Meiselman, H.L., Staddon, S.L., Hedderley, D., Pierson, B.J. and Symonds, C.R. (1994), ‘Effect of effort on meal selection and meal acceptability in a student cafeteria’, Appetite, 23:1, pp. 43–55.

18 Assuming that the relationship between the price and quantity demanded is linear.

19 British Plastics Federation (undated), ‘Deposit return schemes. Stakeholder briefings’, p. 3.

Download

Contact

Dr Leonardo Mautino

PartnerGuest authors

Alexander Smirnov

Federico Galasso

Contributor

Related

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More