Regulatory appeals: do the UK’s appeal regimes stand up to critical review?

In the UK, complex decisions by economic regulators for their respective sectors are reviewed and appealed according to bespoke regimes, and decided by specialist bodies such as the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Dr Gavin Knott, Director (remedies, business and financial analysis) at the CMA, looks at the current appeal regimes and how they might develop in future.

This article represents the views of the author based on his experience of regulatory appeals at the CMA, as a Senior Consultant at Oxera, and as a regulator at Ofcom, Postcomm and Ofgem. It does not represent the views of the CMA or of Oxera.

In the UK, decisions by regulators can be judicially reviewed by the courts on the same basis as any other decisions of public authorities. However, in the case of the decisions of economic regulators, a set of bespoke review and appeal regimes are also in place, to cover decisions such as those relating to price controls and charges for access to regulated infrastructure.1

These regimes are intended to provide an opportunity for an independent review by an expert body of what are often complex decisions requiring specialist economic skills and awareness. The special regimes provide for appeals to be determined in some cases by the CMA (previously the Competition Commission) and in others by the Competition Appeal Tribunal (CAT). This article is concerned primarily with the former.

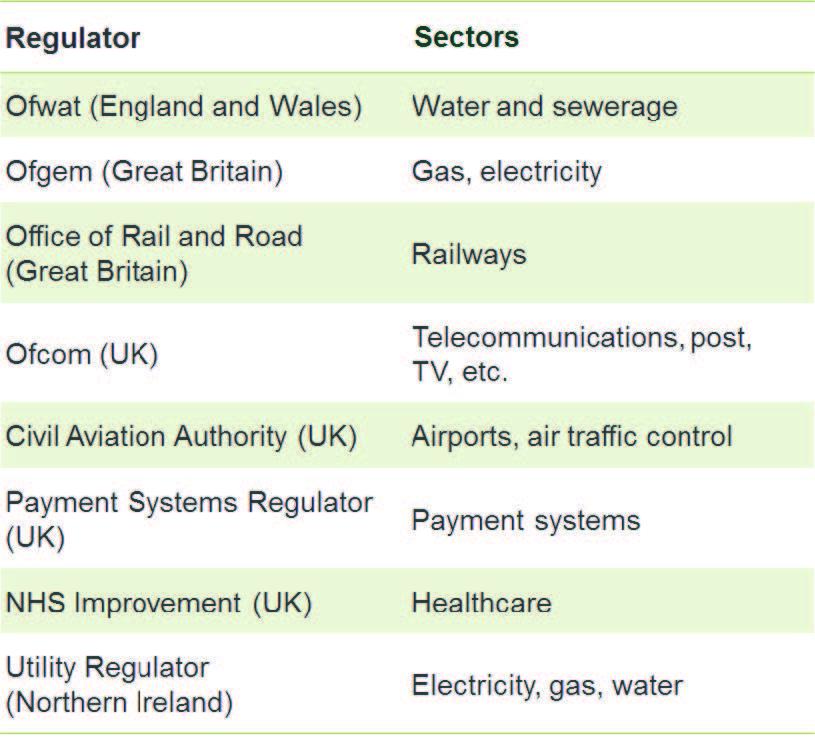

Appeal regimes can take many forms. Those applied by the CMA vary across the regulated sectors. These regimes have developed since the 1980s, and continue to evolve as the nature of regulation and the different sectors change. Regulatory references and appeals can currently be made to the CMA in relation to decisions made by eight different regulators across ten sectors of the economy, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1 The regulators whose decisions can be appealed to the CMA

Having a right to appeal a regulatory decision mitigates two kinds of risk:

- unfair decisions (too harsh on the regulated company or on other market participants such as competitors);

- regulatory capture (too generous decisions, accepting arguments made by regulated companies that give insufficient weight to customer interests).

Each sector has its own legislation setting out the roles of the sector regulator, the CMA and, in some cases, the CAT. In some sectors the appeal rules also have to be consistent with EU regulations, which have also changed over time to reflect developments in both harmonisation across the EU and the model of competition. The CMA’s role therefore tends to change along with developments in the technology and broader regulatory framework of the sectors.

This is illustrated by recent changes that will introduce different responsibilities for the CMA.

First, the telecommunications appeal regime has been changed by the Digital Economy Act 2017. Under the former regime, established in 2003,2 appeals were made to the CAT, but there was an obligation for the CAT to refer price control matters to the CMA, while retaining for itself non-price control appeals. In future, the CMA and the CAT will both be required to review telecommunications appeals ‘having regard to judicial review principles’, rather than, as in the previous regime, ‘on the merits’.

Second, there is the possibility of appeals to the CMA in new, complex and untested sectors—for example, there is now an appeal regime for decisions by the Payment Systems Regulator on access rights in financial services. In relation to airports, the Competition Commission’s mandatory review on public interest grounds of the Civil Aviation Authority’s price control decisions in the 2000s has changed to a two-way appeal system, under which either the airport or affected customers (e.g. airlines) can appeal to the CMA against a regulatory decision. It remains to be seen how the appeal regime will work in practice in these sectors, where regulators’ decisions reflect a broad range of competing objectives.

In the remainder of this article, I provide some observations on the current appeal regimes, and how they might develop in the future.

The current appeal regimes

Regulators’ interventions such as price controls can often have a very material effect on companies that are subject to regulation, other companies that deal with or compete with the regulated companies, and, ultimately, consumers. However, the issues raised in appeals often require an understanding of complex technical matters as well as economic and financial issues. It is not unusual for a specialist tribunal to be set up to deal with appeals or disputes on technical matters, over and above the general powers of judicial review over administrative decisions.

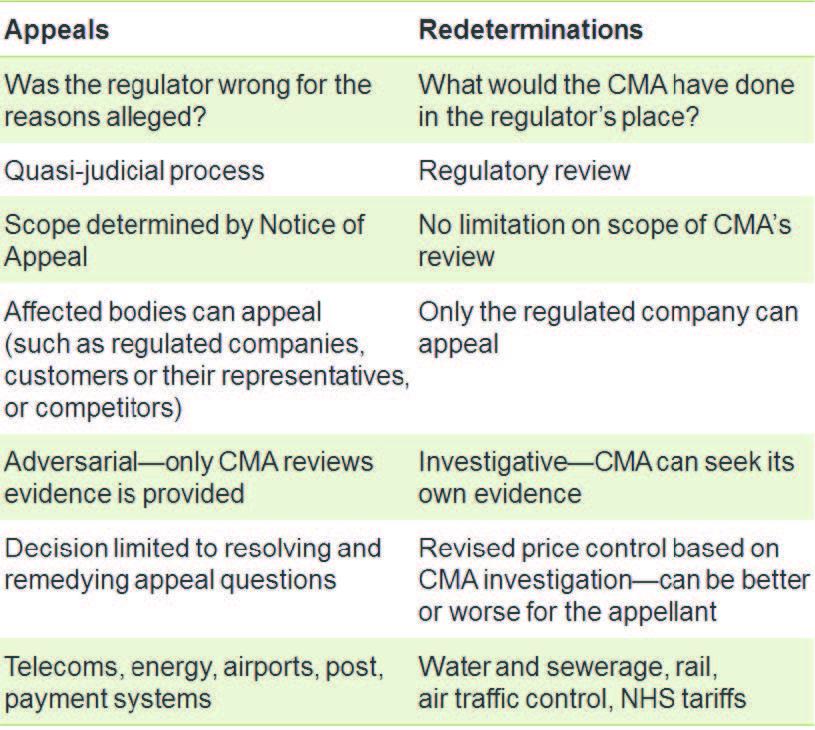

The origin of the current regimes was the ‘redetermination’ function given to the UK Monopolies and Mergers Commission3 and later the Competition Commission following the privatisation of the formerly nationalised industries in the 1980s. This allowed the Monopolies and Mergers Commission/Competition Commission to review the price control decision for an appellant over a six-month period. Some sectors, including water, still have a redetermination function. Other sectors have moved to an adversarial appeal regime, where parties specify ‘Grounds of Appeal’ where they allege that the regulator’s decision was wrong for reasons specified in the appeal.

The table below highlights the differences between appeals and redeterminations.

Table 2 Appeals vs redeterminations

The CMA has a role in regulatory redeterminations and appeals in part because it has the economic and financial expertise and knowledge of markets to make decisions on price control matters. The CMA’s duties in relation to mergers and markets also require prompt decisions within strict statutory timelines, including on the implementation of remedies. Meanwhile, the structure of the CMA, with independent panellists with commercial and regulatory expertise, allows it to act as an impartial appellant body that is able to quickly grasp and review regulators’ decisions. Many of the recent decisions taken by the CMA on appeals relate to how regulation of one company affects effective competition in related markets, and the CMA’s broader experience in competition and markets supports effective decision-making in these appeals.4

At first sight, the appeal function looks more like one that should be performed by a court or tribunal such as the CAT. The CMA is acting in a ‘quasi-judicial’ capacity. This is indeed the reason why the telecommunications and postal services regimes require the CAT to determine non-price control matters in these sectors. However, even here, Parliament has to date regarded the CMA as the appropriate body to deal with price control appeals.

Broadly, the reason for involving the CMA in decision-making in appeals has been because of the need for the appeal body to quickly understand the often complex nature of regulatory decisions. This is consistent with the references in EU regulation in the telecommunications sector to the need for such appeals to take account of the merits.5

Over the last few years there has been a general shift from redeterminations towards appeals, which permits the CMA’s review to focus on what appellants see as the errors in regulators’ decisions, and is consistent with the need for speed in reviewing the decisions. This has some clear benefits: it allows for two-way appeals by customers and companies, and gives more certainty in the application of the price control in undisputed and unaffected areas. There are some other sectors, such as rail or air traffic control, where there might be benefits from a move to a symmetrical and targeted appeal regime.

However, there are also costs to appeals that do not apply to redeterminations. The downside from appealing is limited to the risk of having to pay costs, which creates the perception that appeals by large companies of decisions with material financial consequences could be a ‘one-way bet’, and does not open up elements of a decision that favour an appellant. The costs of a quasi-judicial appeal process may be relatively high for customer groups or small companies, in comparison with a redetermination or other form of dispute resolution process. There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach that will work best for any potential parties to appeals.

The implementation of the appeal regimes: is there a case for change?

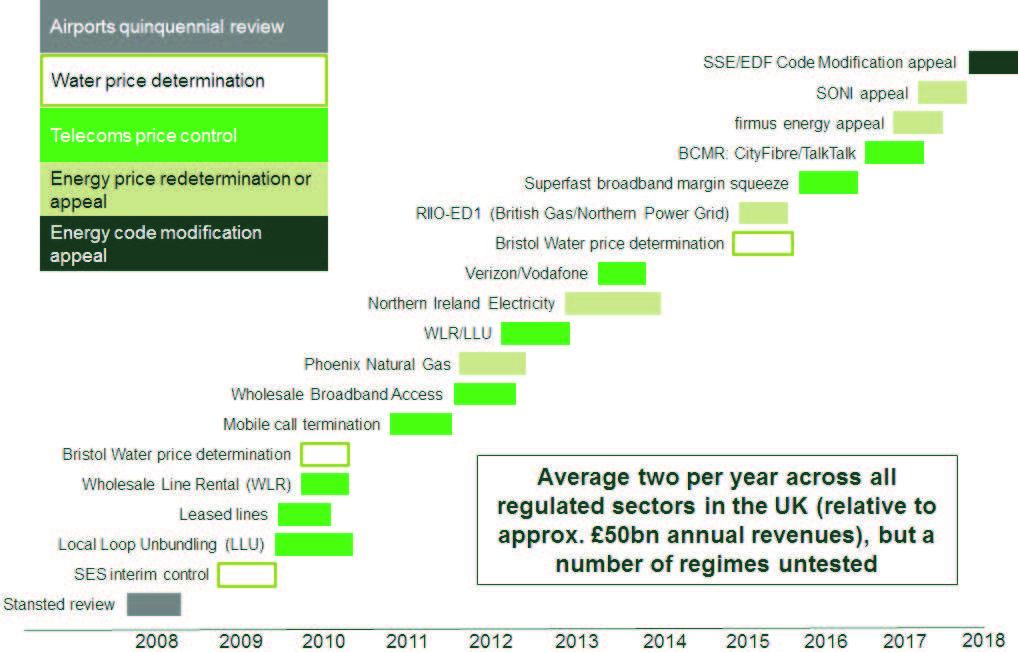

The appeal regimes in the UK are unusual, and in particular the role of the competition authority as an appeal body and the fact that the legal framework varies by sector. I provide some evidence below on how the appeal regime has performed in the past, how it is working today, and how it might continue to change in the future. Figure 1 illustrates the number of appeals that the CMA has performed in the last ten years. It shows that the Competition Commission/CMA has generally heard around two appeals a year, with few repeat appeals related to the same issues as previous appeals in the last few years.

The majority of appeals have been in the telecommunications sector. This in part reflects the fact that the EU regulatory framework for telecommunications requires Ofcom to review each of the telecommunications markets every three years, and as a result it makes more price control decisions than other regulators. In addition, recent appeal cases in the sector have been in respect of decisions that Ofcom has made to take account of how the telecommunications sector has been evolving.

Figure 1 Timeline of CMA appeals

When evaluating the need for change and the effectiveness of the current regime, it is necessary to consider what a good appeal regime looks like. I consider the effectiveness of an appeal regime against four core regulatory principles, as follows:

- does the regime offer good value for money?

- is the appeal regime proportionate?

- is the appeal regime transparent?

- does the regime have its intended effect?

Does the regime offer good value for money?

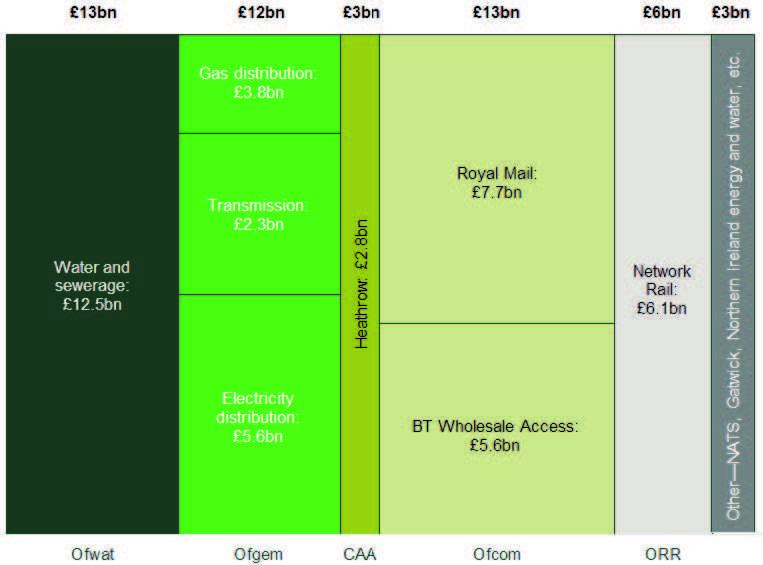

From the perspective of the public purse overall across the regulated sectors, the CMA’s role in the appeals system represents reasonable value for money, given its scope and scale. The total cost to the CMA of managing two to three appeals a year is less than £2m,6 much of which is recovered from the parties to the appeals. The total costs incurred by regulatory bodies in relation to CMA appeals are normally comparable in scale to that of the CMA. The CMA estimates that the aggregate cost associated with the appeals function in recent years has been less than 0.02% of the gross revenues affected across the regulated sectors,7 of over £50bn. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Approximate revenues across regulated sectors

Source: Latest annual reports and regulatory reports.

However, this does not mean the regime is low-cost for all participants, particularly smaller regulators or those such as Ofcom that face frequent appeals. Moreover, the costs may be a deterrent to small companies using the appeal regime. For example, a small company challenging a decision will face the legal costs of preparing an appeal and the risk of paying the CMA’s costs, and in some cases the regulator’s costs, if it is unsuccessful.

Nevertheless, to the extent that the appeal regime supports effective decision-making more generally, the aggregate costs do not appear unduly high given the scale and number of decisions subject to appeal.

Is the appeal regime proportionate?

Under all the CMA appeal regimes, the CMA works within statutory deadlines, and remedies will normally be put in place to resolve any identified errors within this timeframe. The CMA’s powers normally8 include the ability to impose remedies where errors are identified, or to redetermine a new price control. This means that where decisions are found to be wrong, the CMA’s process can resolve and remedy the error within six months.

In addition, the potential outcomes from an ongoing regulatory appeal tend to be limited to a small number of changes where remedies can be implemented effectively, which will normally mean that the uncertainty caused by an appeal has a limited effect on related markets.

Is the appeal regime transparent?

The CMA’s decisions are all published and transparent, as are Notices of Appeal and responses from the regulator. At the start of a case, underpinned by the statutory deadlines, the CMA publishes a clear timetable as to the expected process over the period. Overall, there is more transparency than would be normal under a court process.9

Does the regime have its intended effect?

Having an effective appeal regime should improve customer outcomes by correcting errors in regulators’ decisions in particular cases, but also by encouraging care by regulators in taking such decisions. However, if appeals are overly onerous in themselves, or if an appeal results in frequent changes in the appellants’ favour, parties may use the threat of an appeal to encourage a bias in regulatory decision-making.

However, after 30 years of price control regulation, sector regulators are subject to scrutiny by a wide range of stakeholders and held to a high standard of transparency. A review of recent appeals in which the CMA was required to identify whether regulators made an error suggests that regulators have not been found to have been wrong in those price control assumptions that are repeated across regulatory reviews, such as the efficiency assumptions or the choice of key parameters in the cost of capital.10 Where there have been successful appeals, these have tended to relate to new forms of regulation, where the appeal has identified gaps in the supporting evidence needed to justify the approach taken.

How should the appeal regime evolve in the future?

The rules as to how appeals work across the regulated sectors have changed significantly in the last ten years. It may be puzzling at first sight why there are different appeal regimes in different sectors, but there are good reasons why an appeal regime that works well in one sector may be less effective in another.

In summary, the regulated sectors have different characteristics, and both the operations and the nature of competition and regulation in these sectors change over time. So, perhaps it is no surprise that appeal regimes differ, have changed over time, and are likely to continue to do so.

Gavin Knott

1 Recent cases include disputes over the first price control for the electricity system operator in Northern Ireland since it took on the activities of independent network planning for the system; the rules that Ofcom required BT to follow in setting the price for a new ‘dark fibre’ passive access product; and Ofgem’s decision on an industry code modification in respect of the charges paid by generators for access to the electricity transmission network.

2 Communications Act 2003.

3 Predecessor to the Competition Commission and later the CMA.

4 See Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘Leased lines price control appeals: CityFibre and TalkTalk’, 1 December; Competition and Markets Authority (2016), ‘Superfast broadband price control appeals: BT and TalkTalk’, 20 July; Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Energy licence modification appeal: SONI’, 1 February; and the SSE/EDF code modification appeal: Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘EDF/SSE code modification appeal’, 27 February.

5 See article 4 of the electronic communications framework directive 2002/21/EC as amended by directive 2009/140/EC. This requires ‘an appeal body that is independent of the parties involved. This body, which may be a court, shall have the appropriate expertise to enable it to carry out its functions effectively. Member states shall ensure that the merits of the case are duly taken into account and that there is an effective appeal mechanism’.

6 Over the 18 months to the end of 2017, the CMA’s costs were approximately £1.7m, which comprised the BCMR appeal (CityFibre/Ofcom and TalkTalk/Ofcom appeals) at £480K, firmus/NIAUR at £637K, and SONI/NIAUR at £590K. See Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘Leased lines price control appeals: CityFibre and TalkTalk’, 1 December; Competition and Markets Authority (2017), ‘Energy licence modification appeal: Firmus Energy’, 3 November; Competition and Markets Authority (2018), ‘Energy licence modification appeal: SONI’, 1 February.

7 Based on CMA costs for two appeals of £1m–£1.5m, a similar scale of costs incurred by regulators, and an estimate of appellants’ costs, total costs incurred by all parties will be under £10m per year, relative to around £50bn of affected revenues.

8 There may be some appeals where there is no appropriate remedy other than remittal to the regulator. In addition, under the new telecommunications appeal regime the CMA is not able to impose remedies.

9 While the CMA’s appeals cases have more information in public than a court process, the process is a bit less transparent than some other CMA cases: the CMA does not publish provisional determinations or other submissions from parties in appeals, although there is full transparency in redeterminations. Since appeals are quasi-judicial and more comparable to a court process, the provisional determination is not an open consultation to all stakeholders, but is more like a draft determination, seeking views from parties to the appeal on factual accuracy, clarification of analysis, and confidentiality.

10 In the redetermination process followed in the Bristol Water appeal (2015), the CMA reviewed the efficiency and cost of capital afresh, rather than assessing whether Ofwat had made an error in its own approach.

Download

Contact

Peter Hope, CFA

PartnerGuest author

Gavin Knott

Contributor

Related

Download

Related

Blending incremental costing in activity-based costing systems

Allocating cost fairly across different parts of a business is a common requirement for regulatory purposes or to comply with competition law on price-setting. One popular approach to cost allocation, used in many sectors, is activity-based costing (ABC), a method that identifies the causes of cost and allocates accordingly. However,… Read More

The European growth problem and what to do about it

European growth is insufficient to improve lives in the ways that citizens would like. We use the UK as a case study to assess the scale of the growth problem, underlying causes, official responses and what else might be done to improve the situation. We suggest that capital market… Read More