Road pricing for electric vehicles: bridging the fuel duty shortfall

Governments generate significant revenue from taxes on petrol and diesel, which has been essential in financing and maintaining infrastructure. These taxes are also intended to incorporate the externalities of driving, such as congestion, noise, accidents, pollution and road wear. If these costs were borne by society instead of by drivers and passengers, it could be argued that they would lead to ‘too much’ driving, with taxpayers effectively subsidising motorists.

Electric vehicles (EVs) do not use these fuels and therefore do not contribute to fuel duty revenues. As more drivers switch from internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles to EVs in line with the UK and EU target of all new vehicles being zero emission by 2035, fuel duty revenues will decline, potentially creating a ‘fiscal black hole’. At present, there is also no way to account for the externalities of EVs. EV externalities may be less than those of ICE vehicles because they cause much less local pollution—however, EVs can still cause noise, congestion and accidents.

The tax impact of electric vehicles

Globally, EVs accounted for 3.2% of the car fleet in 2023,1 and their share is expected to grow to 16% in 2030 and 31% in 2035.2 It is estimated that the increase in EV adoption led to a net fiscal loss of around $10bn in 2023. By 2035, the global loss is projected to grow to $105bn.3

The negative fiscal impact of EV adoption will occur disproportionately in Europe, given its relatively high fuel duties. For instance, the petrol tax rates in France, Germany and Italy are more than six times that in China. In Europe, fuel tax revenues are projected to decrease by nearly $70bn by 2035—around two-thirds of the total global reduction.4

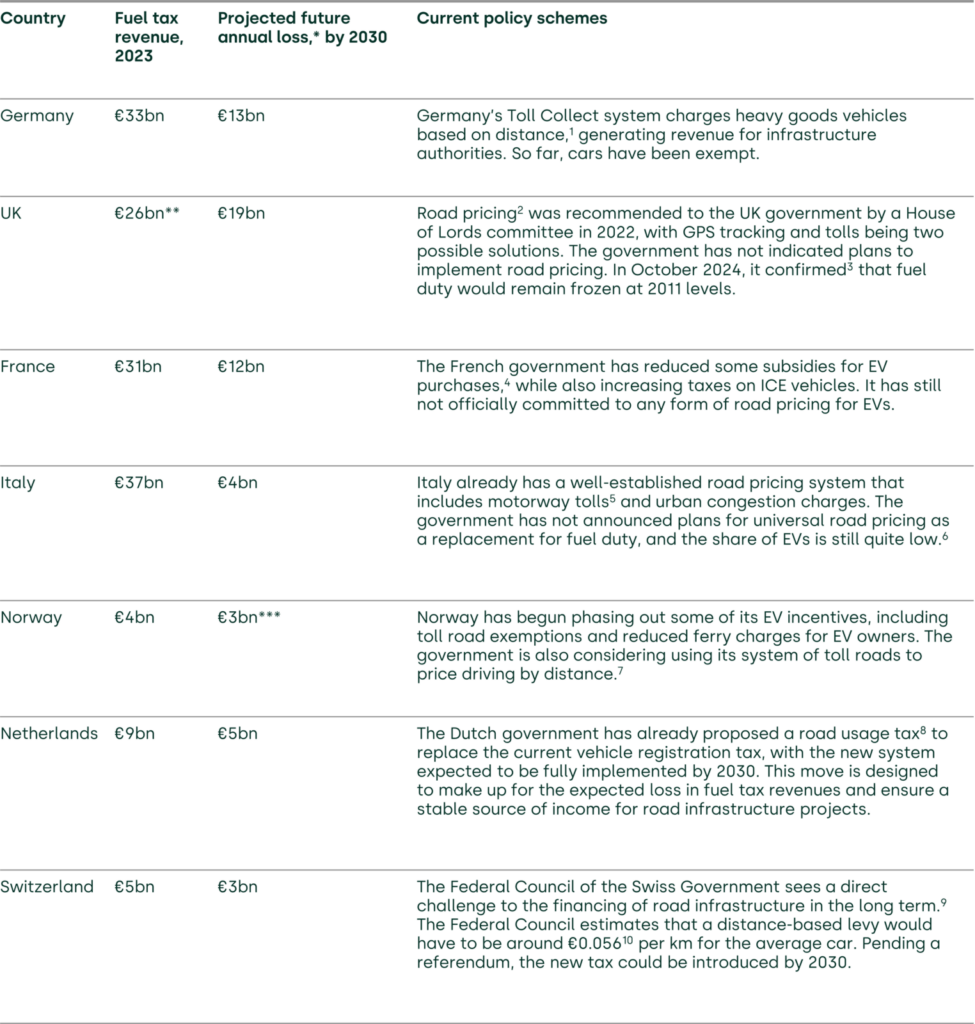

Several European countries are already exploring policies to address these fiscal challenges. Common strategies include gradually phasing out EV adoption subsidies and, in some cases, introducing road pricing for EVs. Table 1 below summarises the projected shortfall in fuel duty by the end of this decade, as well policies relating to road pricing in a number of European countries.

Table 1 Summary of fiscal loss projections in European countries

Source: 1 Federal Logistics and Mobility Office (2024), ‘Toll System Operator’. 2 House of Commons Transport Committee (2022), ‘Road pricing’. 3 HMRC (2024), ‘Autumn Budget 2024: Overview of tax legislation and rates’. 4 Rho Motion (2024), ‘France reduces its EV subsidy, and tightens vehicle CO2 emission penalties amid budget cuts’. 5 Autostrade per l’Italia (2024), ‘How toll rate is calculated’. 6 European Alternative Fuels Observatory (2024), ‘Italy: Vehicles and fleet’. 7 OECD (2022), ‘Norway’s evolving incentives for zero-emission vehicles’. 8 Ministerie van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat (2023), ‘Betalen naar Gebruik: Effecten op autobelastingen en inkomenseffecten’, p. 8. 9 Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft (2022), ‘Konzeption für den Ersatz der Mineralölsteuern (Ersatzabgabe)’. 10 ETH Zurich (2024), ‘Wie können wir Elektroautos besteuern, ohne die Mobilitätswende auszubremsen?’.

The table demonstrates the heterogeneity of policy measures in European countries depending on the extent of EV adoption, as well as the politics of motoring. While in theory a broad consensus around road pricing seems to be emerging, applying it in practice will require careful policy design and transparent communication in order to mitigate opposition and address equity concerns. Balancing short-term political risks with long-term benefits is critical in gaining public support.

Road pricing for EVs

Road pricing exclusively for EVs, in combination with existing fuel duties, could help to address the growing fiscal gap caused by the decline in fuel duty revenues. By targeting EVs with road pricing, governments can ensure that these vehicles contribute fairly to road maintenance and development. This approach has the potential to address the decline in fuel tax revenues without discouraging EV adoption through more punitive measures.

Several countries have considered the potential charge for an average EV. Since early 2024, a distance-based road charge for EVs has been applied in Iceland, at ISK6 (€0.04) per km for electric vehicles and ISK2 per km for plug-in hybrids.5 In Switzerland, the Federal Council estimates that a distance-based levy would have to be around CHF0.056 per km for the average EV to make up for declining fuel duty receipts.6 Although the levy has not yet been introduced, the Swiss government is actively investigating policy designs.7

Economically, road pricing for EVs ensures that drivers pay for the externalities that they cause, even if their vehicles are less environmentally damaging than ICE vehicles. EVs still cause significant wear on roads, particularly due to their greater weight from large battery packs. Without road pricing, EV drivers could be seen as benefiting from ‘free’ road usage, while conventional vehicle owners bear the fiscal burden. Implementing road pricing addresses this imbalance, fostering a system where all road users contribute based on actual usage, rather than on fossil fuel consumption alone.

However, limiting road pricing to EVs could raise concerns about fairness. EV drivers might perceive this policy as a penalty for their environmentally conscious choice. In 2021, the State of Victoria in Australia introduced a charge of AU$0.028 (€0.02) per km for EVs and AU$0.023 (€0.01) for hybrids, thereby excluding ICE vehicles, which continued to pay fuel duty.8 To measure the distance travelled, odometer readings were taken. However, the High Court of Australia struck down the charge in 2023. Although this decision was based on States being constitutionally prohibited from introducing excise charges, it came after a number of citizens’ groups and motorist associations actively campaigned against the charge.9 This shows that public acceptance remains a challenge to any new vehicle-related charge or tax. The same logic seems to apply to fuel duty, as exemplified by the 2024 Autumn Budget in the UK, which confirmed that fuel duty will remain at levels last adjusted in 2011.10

Additionally, road pricing for EVs could discourage further EV adoption at a time when governments are attempting to accelerate the take-up of electric vehicles. To preserve incentives for switching to EVs, policymakers may need to design road pricing schemes that are phased in gradually, possibly paired with incentives such as lower vehicle purchase taxes to balance the increased financial burden on EV owners. In addition, retaining or even increasing fuel duties could preserve the incentives for switching to EVs.

In terms of measuring the distance travelled, a couple of options are currently under discussion. GPS-based systems could provide an accurate tracking solution. Periodically submitting odometer readings is simpler and more transparent, with enhanced privacy and minimal intrusion. However, it does not differentiate between road types, creating a potential pricing distortion.

Conclusions

As fuel tax revenues decline, governments must find alternative ways to fund road infrastructure. It is also important to ensure that the costs of driving—congestion, risk of accidents, noise—are properly internalised by drivers.

Road pricing for EVs is gaining traction as a potential solution in a number of countries. It provides a long-term revenue source as fuel tax revenues fall, and creates a system whereby EV drivers pay for road usage and the externalities that they create. It also encourages efficient driving by charging drivers based on mileage, helping to reduce congestion and environmental impact.

However, such pricing could be perceived as placing an additional financial burden on environmentally conscious drivers, leading to resistance from both consumers and EV manufacturers. Governments may need to commit to introducing road pricing for everyone over time, while keeping or increasing fuel duty for ICE drivers. By acting now, while EV drivers are still in the minority, governments can design balanced policies that ensure fiscal stability without compromising the adoption of clean means of transport.

1 International Energy Agency (2024), ‘Trends in electric cars’.

2 Ibid.

3 International Energy Agency (2024), ‘Global EV Outlook 2024’, p. 152.

4 International Energy Agency (2024), ‘Global EV Outlook 2024’, p. 152.

5 Public Services of Iceland (2024), ‘Kilometer fee for electric, hydrogen and plug-in hybrid cars’.

6 ETH Zurich (2024), ‘Wie können wir Elektroautos besteuern, ohne die Mobilitätswende auszubremsen?’.

7 Ibid.

8Victorian Ombudsman (2023), ‘Investigation into the Department of Transport and Planning’s implementation of the zero and low emission vehicle charge’.

9 Australia Institute (2021), ‘25 Organisations Open Letter: Victoria EV Tax Worst EV Policy in the World’.

10 HM Treasury (2024), ‘Autumn Budget 2024’.

Contact

Fernanda Scianna

Senior ConsultantContributors

Related

Related

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 2 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the second of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More

The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say? (Part 1 of 2)

On Thursday 23 October in Brussels, Oxera hosted a roundtable discussion entitled ‘The new electronic communications and digital infrastructure regulatory framework: what does the economic evidence say?’. In the first of a two-part series, we share insights from this productive debate. The discussion took place in the context of an… Read More