Should we be cross about cross-subsidies? Experience from the financial services sector

Cross-subsidies, where one group of consumers pays a higher amount so that the price paid by another group can be reduced, are common in many markets. But the practice may raise concerns about whether firms are exploiting those consumers who pay more, and can lead to calls for competition authorities or regulators to intervene. How might we assess whether cross-subsidies represent a problem? We look at examples from the consumer credit sector.

Cross-subsidies occur in a wide range of markets, when a firm charges lower prices to one group of consumers, who are then subsidised by the higher prices charged to another group. Examples include student discounts, teaser rates for new customers, loss-leader products in supermarkets, and free-if-in-credit bank accounts. Cross-subsidies can occur between different consumers buying exactly the same product, but also between consumers buying different combinations of products, so the concept of cross-subsidy captures a broader range of situations than pure ‘price discrimination’, where exactly the same product is sold at different prices to different consumers.1

Careful analysis is required to ascertain whether cross-subsidies are really occurring, as any firm will face common costs (e.g. overheads) that it needs to share across its customers, and some consumers may be contributing more to those common costs than others. There is a significant body of literature on cost-allocation methodologies and the measurement of economic profitability,2 which has been a key issue in many competition and regulatory investigations.3 Strictly speaking, economists refer to cross-subsidies in a narrower range of situations, where certain groups of consumer products are priced below their ‘economic cost’—i.e. they contribute less in revenues than the incremental cost to the firm of serving those consumers. In this narrower sense of cross-subsidy, the firm could in principle increase its profits (in the short run) by not serving those loss-making consumers who do not cover their economic cost, but it is able to continue to do so due to the profits it makes from serving other consumer groups.

In this article, we consider this narrower concept of cross-subsidies, why they may arise, and whether they should be a cause for concern. We focus on examples from the consumer credit market, where issues with consumer behaviour have meant that cross-subsidies have been a key issue for regulation. This provides some insights into how firms can consider whether cross-subsidies between their own customers could be a cause for concern.

Why might cross-subsidies arise?

Profit-maximising firms should not want to serve loss-making consumers. In reality, however, a firm may not know whether a new customer will be profitable when they are first offered services. From the firm’s perspective, there can be good reasons to offer the new customer highly competitive (and, indeed, loss-making) services to attract them, in the hope of providing more profitable services in due course. A bank may offer the basic facility of a personal current account for free, in hope of attracting customers who then may use additional, more profitable ‘services’, such as holding significant deposits in the current account, or using overdraft facilities.4

From the point of view of society, there is no clear case for these practices being either harmful or beneficial. This was acknowledged in a 2016 FCA paper, which noted that ‘such pricing [practices] may encourage competing firms to charge lower prices to win customers and may make all consumers better off than uniform pricing.’5 But cross-subsidies can also be a signal of weak price competition for certain consumers. In addition, the distributional consequences—some consumers benefiting from lower prices, with others paying more—may be deemed unfair. This could particularly be the case if the consumers who pay more are deemed to be ‘vulnerable’, or are exhibiting behavioural biases that suggest they are unable to participate fully in the competitive market, to their detriment.

So how can we judge when cross-subsidies are an acceptable feature of a competitive market, and when they reflect a concerning issue for market functioning?

As the FCA stated, ‘assessing whether pricing practices are harmful to consumers and competition requires a case-by-case assessment.’6 The consumer credit market provides some interesting examples, due to its potential for both procompetitive and less beneficial outcomes from cross-subsidies.

Cross-subsidies in consumer credit

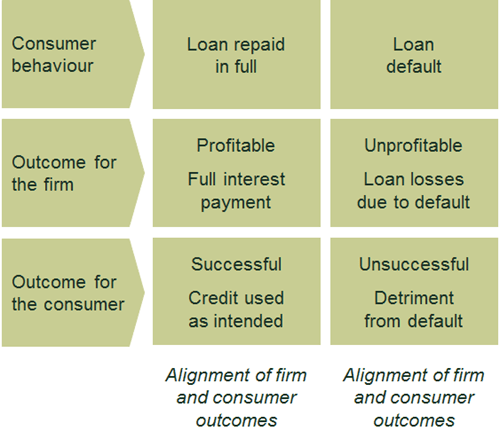

Cross-subsidies are inherent in consumer credit. Borrowers who default are cross-subsidised by borrowers who repay, just as insurance policyholders who make a claim are cross-subsidised by those who do not. The lender (as with the insurer) is fully incentivised to manage this situation, by identifying the higher-risk individuals and charging them more (or excluding them altogether). The interests of the lender are therefore aligned with those of the consumers (the borrowers) who repay, as in a competitive market the lender that is better able to manage default risk can offer its customers lower prices. Figure 1 summarises this alignment of lender and borrower interests in a well-functioning consumer credit market.

Figure 1 Firm and consumer outcomes in a well-functioning credit market

Source: Oxera.

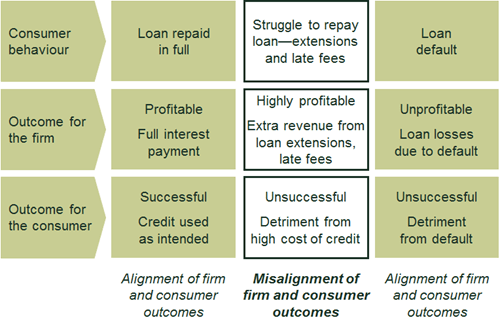

This basis for effective market functioning can come unstuck if the lender is able to profit much more from consumers who use a lot of credit. A borrower who is over-indebted and has a lot of debt, held for a long time, can be very profitable for the lender, particularly if there are additional fees associated with late payments or extensions to the loan duration. This situation can be exacerbated by significant customer acquisition costs in financial services markets, which mean that profits are naturally higher for consumers who stick with the same provider, as the one-off acquisition costs are spread over a longer time.

This creates the risk of an additional dimension to cross-subsidy, with those struggling with debt (i.e. delaying repayment) cross-subsidising those who are not. Struggling with debt is associated with forms of behaviour—which economists refer to as behavioural biases—that can reduce the ability of the borrower to make good decisions and find the cheapest option. These include:7

- optimism bias—consumers may be over-confident in their ability to repay, or may not judge future outcomes appropriately when using credit;

- present bias—a decision may be unduly influenced by consideration of present needs at the expense of future needs, leading to regretful purchases;

- framing effects—consumers may perceive costs expressed in percentage terms as being smaller than the same costs expressed in monetary terms (£/€).

This creates the risk of a conflict in the alignment of lender and borrower interests, as summarised in Figure 2. The lender can make the highest profits from the new middle group—borrowers who have a high risk of default, but from whom sufficient profits can be made in the meantime (for example, from late payment fees and high interest payments).

Figure 2 Firm and consumer outcomes where there is a misalignment of incentives

This dynamic is likely to occur to some extent in any consumer credit market. Some people always use more of a service than others, and these people will typically be more profitable for the lender. So at what point does this dynamic become a concern, and how can regulators and firms spot when market functioning is being corrupted? The relevant indicators can be illustrated through the example of the high-cost short-term credit market in the UK, and by looking at how market functioning can evolve through regulatory intervention to address these issues.

A need for effective regulation: high-cost short-term credit

High-cost short-term credit (HCSTC) is the FCA’s term for typically small loans of less than 12 months with interest above 100% APR, aimed at ‘subprime’ consumers who often have chequered credit histories and consequently a high perceived risk of default. When this sector first came under the regulatory spotlight, in 2013, it was dominated by ‘payday loans’, which were small loans (typically around £100–£500) due to be repaid at the borrower’s next payday, to cover short-term cash-flow needs. The market provides an interesting case study into how market functioning was affected by cross-subsidies, but also how that dynamic has now changed with the introduction of a new regulatory framework.

Since 2013, payday lending has been the subject of intensive regulatory review. Investigations into the sector were conducted first by the Office of Fair Trading (OFT) and its successor, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA), and then by the FCA. One of the key concerns of these regulators was lenders’ reliance on revenues earned as a result of consumers incurring late fees, extending loans, or relending. The initial investigation by the OFT8 found that half of lenders’ revenues were coming from the 28% of loans that were rolled over or refinanced at least once. This indicated that lenders were, to a significant extent, relying on borrowers who were over-using a service meant for short-term credit needs.

In terms of behavioural economics, some consumers (but certainly not all) exhibited optimism bias, by overestimating their ability to repay. They took out a single-period loan, expecting to be able to repay it on their next payday, and when this was not possible they incurred late payments and loan extensions (roll-overs). This dynamic altered the nature of competition in the market. The profits from these borrowers who extended loans encouraged some lenders to increase spending on customer acquisition to such an extent that it meant that lending only once to a borrower who repaid on time became unprofitable—the original OFT investigation found that customers would be profitable only as a result of relending, extensions and late payment fees.9

This meant that, on average, borrowers who struggled to repay debt cross-subsidised those who repaid on time (in addition to those who defaulted). This in turn meant that the incentives of the lender were no longer aligned with those of the consumers who repaid, which in turn led to lender conduct issues. The incentive to conduct thorough credit-risk assessments could be reduced if the highest profits came from relatively high-risk borrowers struggling with debt.

In addition, borrowers struggling to repay debt were less able to benefit from competition in the market to obtain a better deal. In its market investigation, the CMA found that, while it is relatively easy to shop around for a better consumer credit deal (compared to searching for other financial products), payday consumers could be reluctant to switch due to concerns about the availability of loans and the application process.10 The behaviour of consumers therefore also affected the competitive dynamics of the market.

Fundamental change to market functioning

FCA regulation of the sector from April 2014 has changed this dynamic. Lenders are no longer able to profit from excessive lending, as regulation restricts roll-overs, late fees and the ability of lenders to collect payments from those struggling with debt.11 Measures from the CMA have also bolstered price competition.12 This means that lenders can no longer benefit from behavioural biases to the same extent. Instead, lenders now rely to a much greater extent on the contractual interest payments agreed with consumers upfront, rather than revenues from late fees and roll-overs that the consumer might not have expected when agreeing the loan.

Market functioning has therefore fundamentally changed.13 Business models are better aligned with consumer interests, without the reliance on behavioural biases. In terms of the framework set out above, this means that the HCSTC market now looks more like Figure 1 than Figure 2.

However, it is important to consider both the costs and the benefits of such rapid regulatory change. The impact of regulation, including the price cap, on access to HCSTC was much greater than the FCA expected when it set the cap in 2014. The FCA expected a decline of approximately 250,000 consumers per year, whereas the actual decline has been around 600,000 consumers per year.14 Some of these consumers will have been able to turn to other credit sources, but as HCSTC serves the subprime market, many will not have been able to do this.

Applying these lessons to other areas

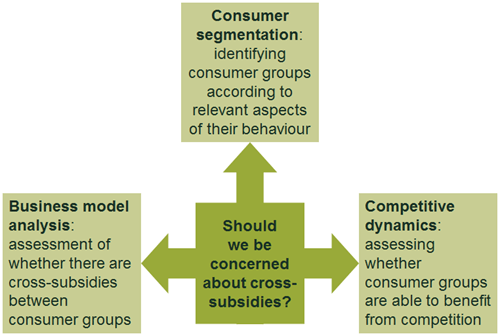

These dynamics, due to a misalignment of consumer and firm interests, could arise in a wide range of areas, given that cross-subsidies between different consumer groups are fairly common. The important aspect here is the link between consumer behaviour, firms’ business models, and competitive dynamics. Potential reliance on behavioural biases is the key question in assessing cross-subsidies. Is the business making profits from normal behaviour consistent with the competitive market, or is the model relying on biases, and consequently a lack of effective competition in some areas?

For example, when the FCA looked at another part of the consumer credit market—credit cards—it segmented the customer base according to consumer behaviour, then examined whether there were cross-subsidies.15 It looked at ‘revolvers’ (customers who carry balances, paying off those balances over time and thus ‘revolving’ them) and ‘transactors’ (customers who use credit cards to make transactions and then pay off the balance in full each month). The FCA found that both groups could be expected to be profitable, and that cross-subsidies were not related to behaviour. There are cross-subsidies in credit cards—for example, many companies offer teaser rates for new customers—but as these were not found to be linked to behaviours, they did not raise the same concerns as with payday lending.

Businesses can assess these issues in their sector by looking at their customers’ behaviour. For example, consumers can be segmented into groups according to aspects of their behaviour that are relevant to the product, such as their use of debt in the case of consumer credit. The nature of the business model can then be considered in terms of the profitability of those groups, using the concept of cross-subsidies as described in this article. This will help to identify whether the business model is overly reliant on behaviours that might go against the consumer interest. The competitive environment can also be considered, to understand whether there are reasons why certain consumer groups (defined by behaviour) are less able than others to take advantage of competition in the market to obtain a better deal.

This concept is summarised in Figure 3. The framework requires a combination of consumer segmentation based on behaviour, business model analysis, and assessment of competitive dynamics. The approach provides a basis for assessing whether cross-subsidies between consumers are simply a reasonable outcome of a competitive market which, as the FCA acknowledges, can be in the interests of consumers, or if they represent a more concerning indicator of business models acting against the interests of consumers, or an issue with market functioning.

Figure 3 Framework for assessing the relevance of cross-subsidies

1 There is a body of literature that looks at the economics of price discrimination. For a summary of the key issues, see Oxera (2015), ‘The Cloud, or a silver lining? Differentiated pricing in online markets’, Agenda, May.

2 Oxera has long been involved in this debate. For example, see Oxera (2003), ‘Assessing profitability in competition policy analysis’, July, prepared for the Office of Fair Trading.

3 For example, the allocation of costs came up as an important issue in the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s (FCA) market study into insurance add-on products. See Oxera (2014), ‘Adding up the add-ons: the FCA’s first market investigation’, Agenda, May.

4 Deposits held in current accounts will be profitable for the bank if it can earn higher interest on the sums held than it pays to the account holder, which is usually the case. Banks also typically charge for overdraft facilities.

5 Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Price discrimination and cross-subsidy in financial services’, Occasional Paper No.22, September, p. 3.

6 Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Price discrimination and cross-subsidy in financial services’, Occasional Paper No.22, September, p. 3.

7 For an in-depth look at consumer behaviour with regard to credit cards, see Agarwal, S. and Zhang, J. (2015), ‘A review of credit card literature: perspectives from consumers’, FCA, 19 October.

8 Office of Fair Trading (2013), ‘Payday Lending: Compliance Review Final Report’, p. 2.

9 Office of Fair Trading (2013), ‘Payday Lending: Compliance Review Final Report’.

10 See Competition and Markets Authority (2015), ‘Payday lending market investigation: final report’, February, paras 6.46–6.68.

11 For example, lenders are now allowed only two attempts to collect payment with the widely used continuous payment authority (CPA). See Financial Conduct Authority, ‘CONC 7.6 Exercise of continuous payment authority’, FCA Handbook.

12 The CMA measures have included increasing transparency of pricing information, and mandating that all lenders are listed on at least one price comparison website. See Competition and Markets Authority (2015), ‘Payday lending market investigation: Order 2015’.

13 For a summary of the changes in this sector since the introduction of FCA regulation, see Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Call for Input: High-cost credit including review of the high-cost short-term credit price cap’, November.

14 See Consumer Finance Association (2017), ‘Impact of regulation on High Cost Short Term Credit’, March.

15 See Financial Conduct Authority (2016), ‘Credit card market study: Final findings report’, MS14/6.3, section 6.

Download

Related

Future of rail: how to shape a resilient and responsive Great British Railways

Great Britain’s railway is at a critical juncture, facing unprecedented pressures arising from changing travel patterns, ageing infrastructure, and ongoing financial strain. These challenges, exacerbated by the impacts of the pandemic and the imperative to achieve net zero, underscore the need for comprehensive and forward-looking reform. The UK government has proposed… Read More

Investing in distribution: ED3 and beyond

In the first quarter of this year the National Infrastructure Commission (NIC)1 published its vision for the UK’s electricity distribution network. Below, we review this in the context of Ofgem’s consultation on RIIO-ED32 and its published responses. One of the policy priorities is to ensure… Read More